We were away for a month and it has taken time to work through the backlog that inevitably builds up over such a mid-year absence. In the meantime, a fair bit more detail has emerged about the Orr/Quigley/Willis saga, between various OIA responses to me, one I’ve seen to another person, a bit more on the Bank’s extravagant new Auckland premises, the Bank’s Annual Report, and the pro-active (but very belated) detailed disclosures about the Orr golden payoff (other OIA responses are still being slow-walked by the Bank). And, of course, we’ve had the announcement of the new Governor and the, perhaps predictable and certainly appropriate, notice of resignation by the temporary Governor (and substantive Deputy Governor). I may eventually get to writing about some of that material, but I have updated my timeline of the Orr/Quigley/Willis saga where relevant.

The Reserve Bank isn’t exactly, in the jargon, a “learning organisation”, but more akin to one determined never to acknowledge a mistake (in a field in which, with the best will in the world, uncertainty means mistakes are pretty much inevitable). The last of the old guard – the Orr team – was at it again last week. Orr may have gone months ago, but Christian Hawkesby (who was the DCE responsible for monetary policy throughout the Covid period itself) is serving out his last few weeks, the other foundation MPC member (Bob Buckle) left just a few weeks ago, and no one expects the manifestly unqualified Karen Silk, the Orr DCE responsible for monetary policy for the last few years, to survive much longer. (There is the old and problematic board too, but monetary policy isn’t their field.) But the face of the latest effort in defence was the chief economist, another Orr groupie, Paul Conway (among many, the line that sticks with me was his closing remarks at the Bank’s early March conference, about having “lost a much-loved Governor”). Time is moving on but they seem determined to defend the Orr legacy, in which they’d all played greater or lesser parts. Specifically, the hugely expensive and risky LSAP.

There were a number of pieces released last Wednesday (links to them all here), headlined by a speech in Australia by Conway, supplemented by some comments from Conway in a Herald article on the Bank’s case (that really the LSAP paid for itself and, what’s more, it is really hard to assign any blame). Of the Bulletin article, “Pandemic lessons on the monetary and fiscal policy mix” by a couple of staff economists I haven’t got much to say: it is wordy and despite 10 pages of references offers little or no insight on the issues or the institution. Perhaps the only line in it that really caught my eye was a heading that claimed that fiscal and monetary policy “Coordination is an intricate and dynamic challenge”, a claim which not only seemed quite wrong, but also at odds with the thrust of Conway’s comments on that issue in his speech (where he seemed, rightly in my view, to be suggesting that what was needed was independence in operations, but keeping each other informed, and exchanging views on what works, what limitations there might be etc). As it ever was, but perhaps now institutionalised in that the Secretary to the Treasury is a non-voting member of the MPC. (Of course, the Treasury is also charged formally with monitoring the performance of the Bank, but the last 18 months suggests how hopeless they’ve been in that role.)

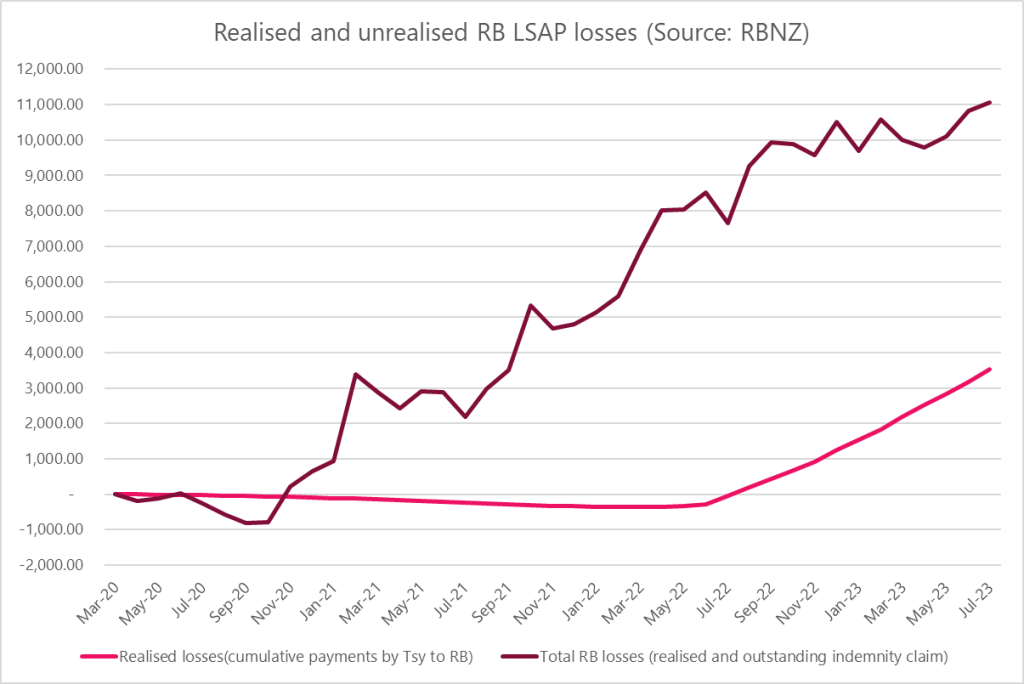

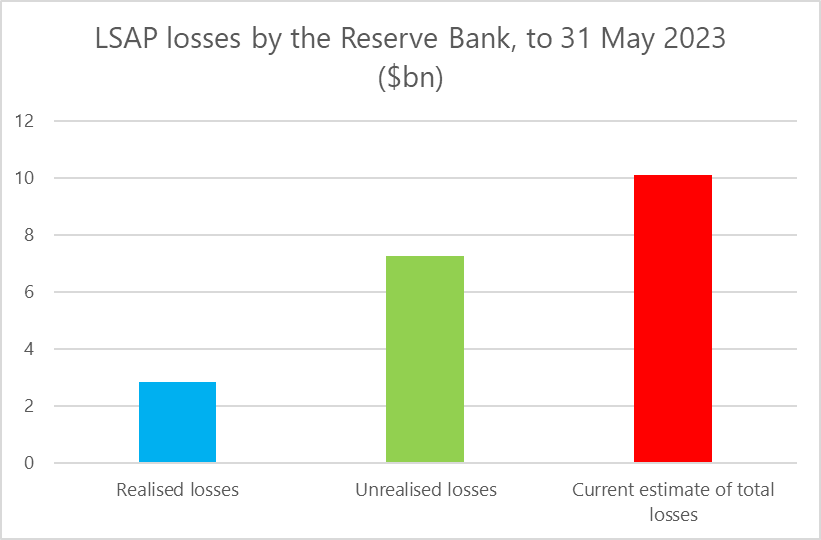

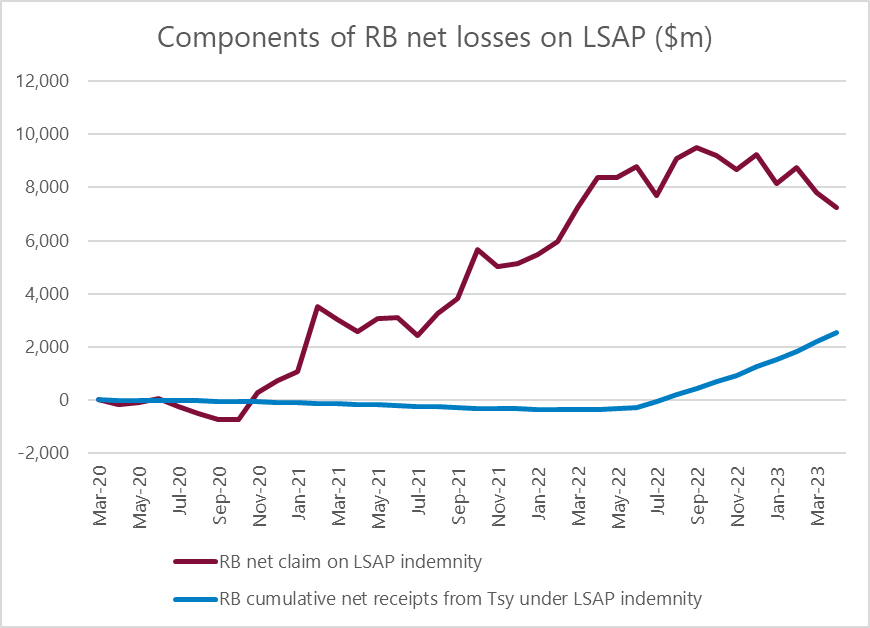

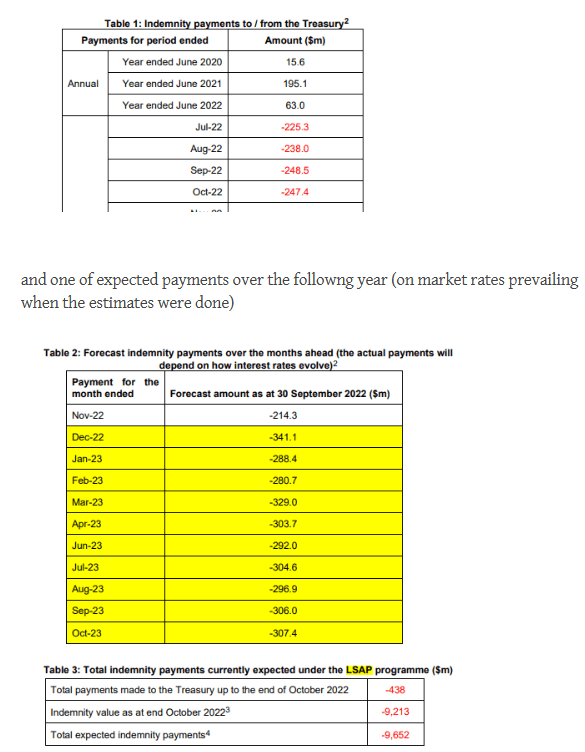

The centrepiece of what the Bank released last week is an Analytical Note by some of their researchers and some IMF staff which uses a model developed at the IMF to attempt to show that really the LSAP was a great success – macroeconomically and that it paid for itself (notwithstanding the $11 billion or so of direct losses incurred). It is a more elaborate version of the framework used by the IMF in a brief early note attached to their 2023 Article IV report (and talked up at the time by the former Governor as offering the “proper story” not some “piecemeal accounting story”), a piece whose claims I unpicked in a post at the time (link a couple of lines up).

So much money has been lost by central banks in the Covid QE interventions – in countries across the advanced world – that too many of those institutions, and their institutional allies (places like the IMF), now seem determined to try to prove a very weak case, that it was really all worthwhile (a case only made harder given the inflation mess that many advanced countries then went through, and which we are still living with the aftermath of). The effectiveness of generalised QE in government bonds – as distinct from specific interventions in dysfunctional markets – has been debated for 10-15 years now but my prior going into Covid was pretty much that of the eminent UK economist Charles Goodhart who in a Foreword to a book I reviewed some years ago (book completed just prior to Covid) opined that in his judgement:

“the direct effect on the real economy via interest rates, with actual or expected, and on portfolio balance, was of second-order importance, QE2, QE3 and QE Infinity are relatively toothless”.

It seemed to be pretty much the Reserve Bank’s approach then too (see this substantive interview with Orr in August 2019, and even just prior to the launch of the LSAP the then chief economist was quoted as playing down the likely impact of such policies), with an explicit preference from the Governor to use negative interest rates (as in Europe and Japan) instead.

I don’t want to bore readers with an interminable critique of all the papers (having already run various posts – eg here in response to some of their earlier claims – over the years of my scepticism that this big asset swap – all it was – made much useful difference to anything, to justify the risk and losses the Bank incurred for the Crown).

So I’m going to work backwards, responding to some of the easier-to-rebut assertions, and only at the end coming back to specific concerns about the particular model they are using in support (recall the distinction between support and illumination).

First, some Conway claims reported in the Herald article

“Conway said it was difficult to isolate the impact of a single tool the Monetary Policy Committee used at a time the Reserve Bank and Government were throwing a lot at the economy to keep it buoyed. He also recognised the collective response caused prices to soar. However, he cautioned against people assuming money printing was largely to blame for the economy overheating.”

You might easily forget reading that that the way our system is set up the Reserve Bank moves last. If the economy overheated – and on everyone’s reckoning it did (both IMF and Reserve Bank positive output gap estimates were very large) – it is the MPC’s fault. It is their job to, as far as possible, lean against the economy overheating (or the opposite) and keep core inflation near the target midpoint. They failed, and that is on them not on the government of the day (which might have run bigger deficits than many were comfortable with, but those deficits weren’t kept secret – most especially from the MPC). Whether or not the LSAP made much difference to demand (Conway believes it did), the responsibility clearly rests with the overall package of monetary policy measures – OCR setting, LSAP, and the Funding for Lending programme (that went on offering cheap loans to banks until the end of 2022). There is no sign in his speech, press release, or interview that Conway – and presumably his bosses – ever really accept that responsibility/blame. Nor is there any real mention of what was actually at the root of the problem: an egregious forecasting failure. Like many/most other forecasters – but unlike them actually wielding power and responsible for outcomes – the MPC badly badly misread the state of demand and resource pressures through Covid, and the result was the inflationary mess that followed. It was hard to get right – few did – but when you take the role you need to take the responsibility. All too few central bankers have. Conway wasn’t there when the worst mistakes were being made, but he now speaks for the institution (and, currently, specifically for Hawkesby, who held the critical role of DCE responsible for monetary policy when it mattered).

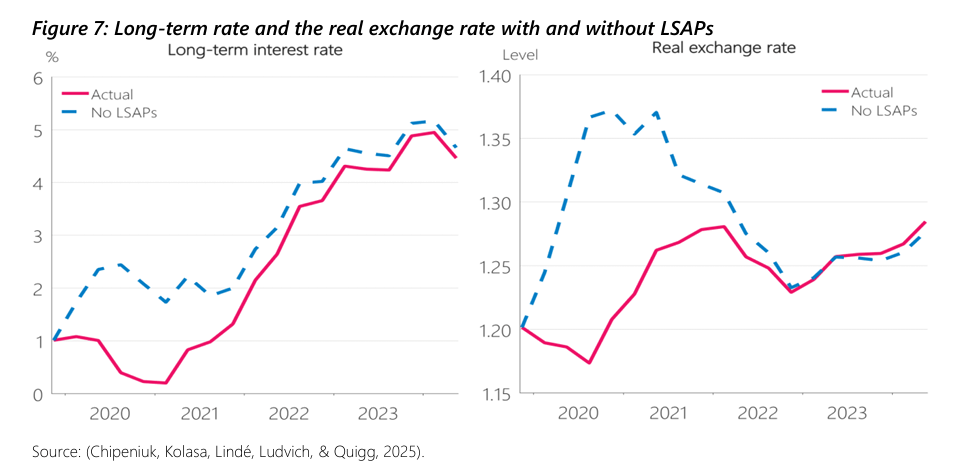

But if the forecasting mistakes were pretty common and widespread (inside and outside central banks, here and abroad), the most evident costly failure is purely on the Reserve Bank itself. This is from Conway’s speech

In other words, even granting for the moment the Bank’s view that the LSAP did a lot of good to justify the large losses, really they would prefer not to have used it at all, because a modestly negative OCR would have achieved the same (claimed) benefits without the massive financial risk and actual $11 billion in losses to the taxpayer. Last week’s papers use quite a bit of the passive voice, suggesting that the inability to use negative rates had been something quite out of their control, perhaps something banks were to blame for. Someone, anyone, no one…but certainly not the Bank.

Actually, it was all on the Reserve Bank. An internal working party in 2012 had recommended (I chaired it) that the Bank ensure our own systems and those of banks were able to cope with negative rates should they ever be needed. The then Governor accepted those recommendations, but it seems that nothing happened until it was far too late (it wasn’t until Covid was almost upon them that the Bank realised nothing had been done and some banks – apparently it wasn’t even all – weren’t operationally capable). It is all the more extraordinary because in the second half of the decade the Bank had clearly been doing preparatory thinking for coping with the next severe downturn – there was a thoughtful Bullletin article on options in 2018, and of course that serious interview of Orr’s I’d linked to earlier. But no one seems to have done the basic engine-room sort of work, reviewing with banks their ability to cope with an instrument used in other countries for many years by then. There was turnover at the top – Orr came on board in March 2018, Hawkesby in March 2019 – but it isn’t as if in mid 2019 these should have been remote issues (the OCR had been cut to its then lowest ever level of 1 per cent, and it wasn’t going to take a particuarly savage shock to put zero in view). And yet nothing was done and – on the Bank’s own telling – the cost to the taxpayer was the full $11 billion or so (since they themselves now say they could have had the macro benefits they claim without the risks/losses if only they – Orr, Hawkesby, the 2019 MPC – had ensured basic operational readiness). That was on them, and only them. (Incidentally, the Bank reckone that by Q42020 those issues were sorted out, and yet they went on taking additional LSAP risk – and then incurring further losses – well into mid 2021.)

A learning organisation, the sort that acknowledges mistakes and learns from them, would be quite open about the cost of their own failure. The Hawkesby/Conway Bank, not so much.

All that was on the assumption the Bank was right and there were huge gains achieved through their monetary policy efforts, notably including the LSAP purchases/punt.

And that rests on two propositions. The first is that there were substantial boosts to GDP, and second that government tax revenue was permanently higher as a result.

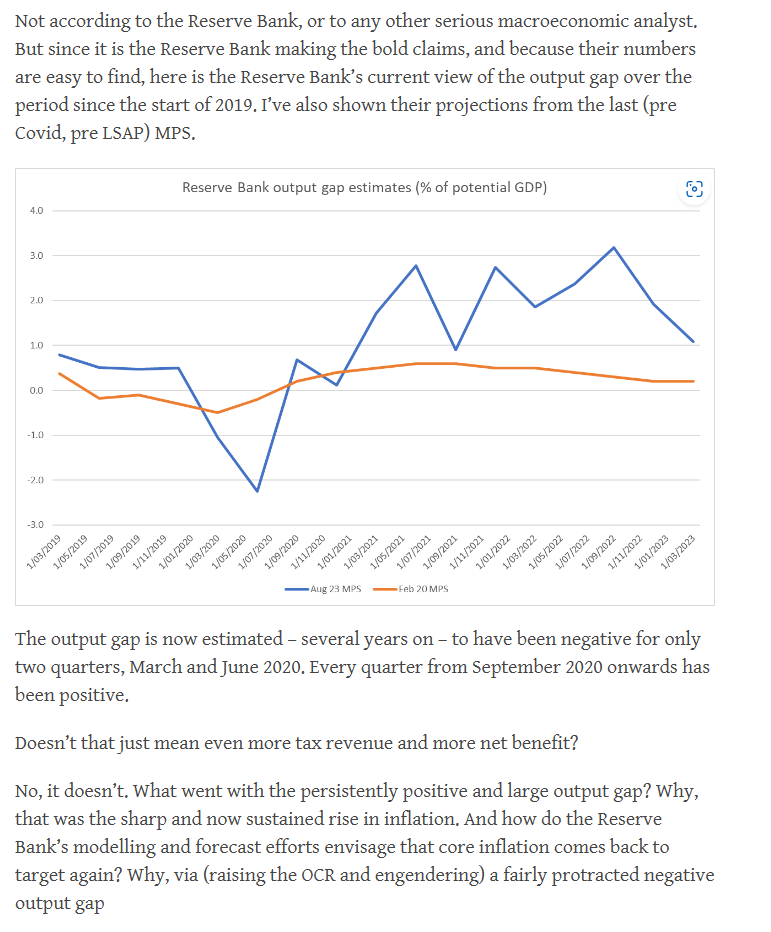

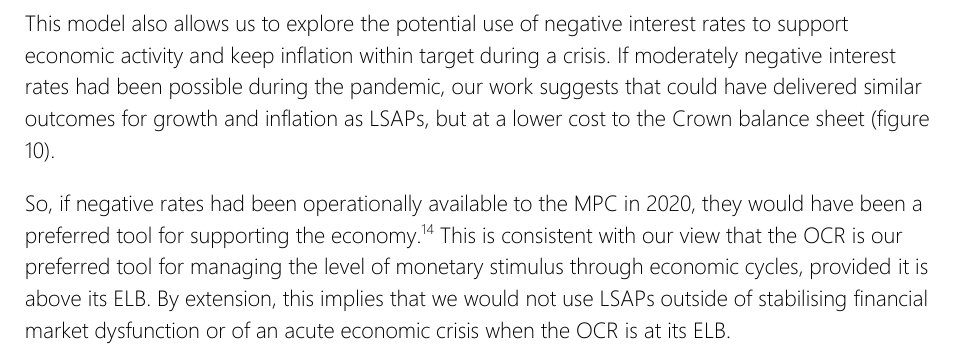

Conway used this chart (from the Analytical Note modelling effort)

(No, they aren’t saying tax revenue got to 42 per cent of GDP; it is just an illustrative device).

In principle, if there had been a very deep hole in economic activity which monetary policy choices had closed much quickly than otherwise, there’d also be a windfall gain in tax revenue. (That was the scenario for the highly questionable little IMF exercise in 2023 linked to earlier.)

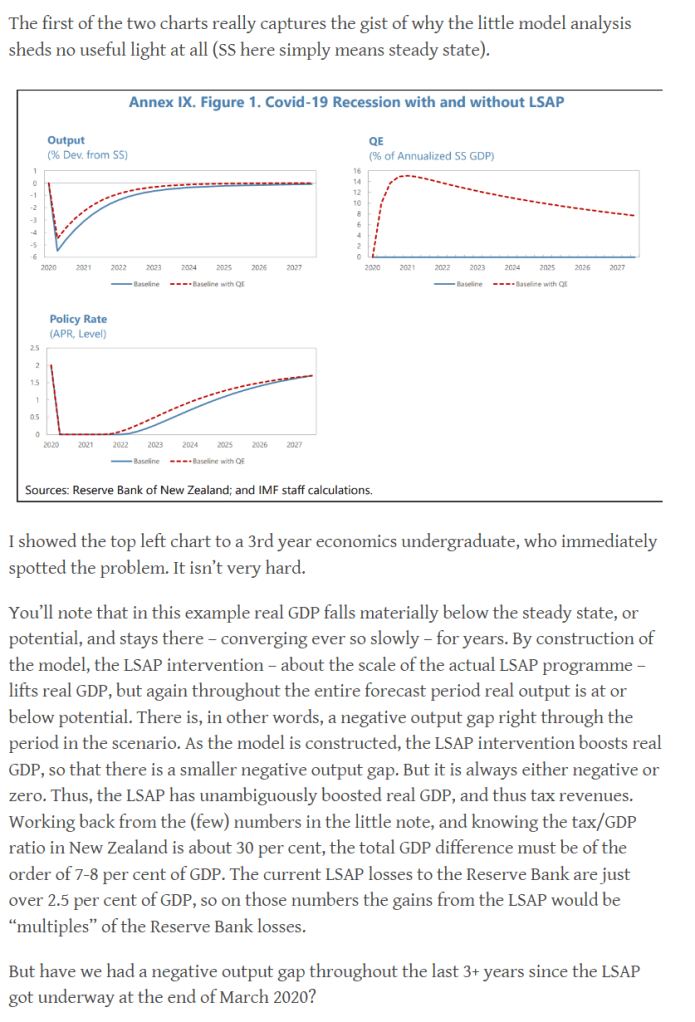

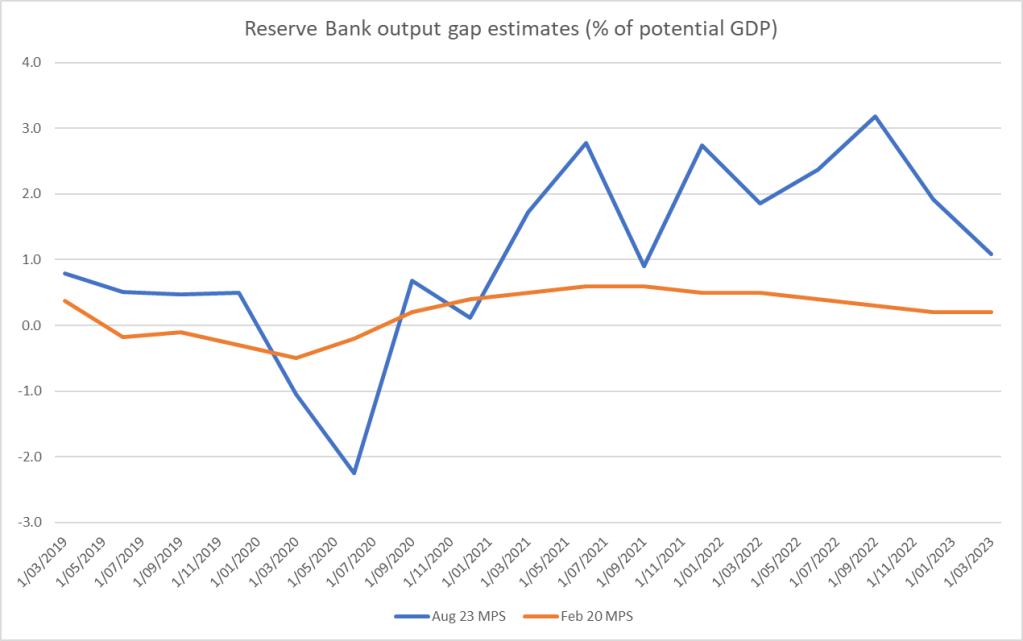

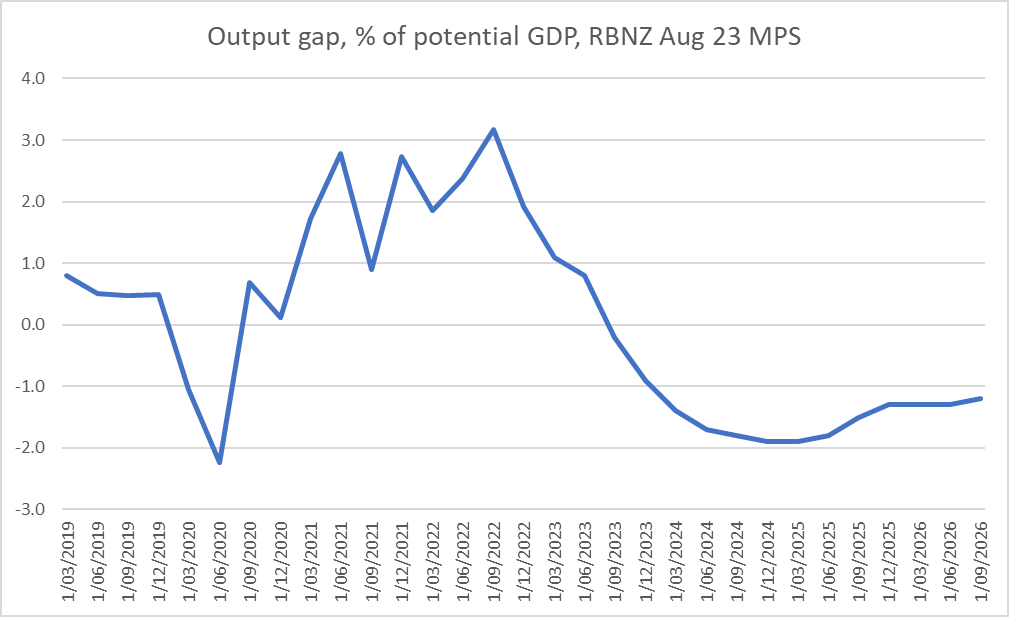

Unfortunately, while in 2020 the Bank thought there was such a hole (eg as late as the November 2020 MPS the Bank thought there was a negative output gap of about 2.5 per cent, which would persist around those levels for the whole of 2021), they are now quite clear in there view that there was no such hole. In their most recent projections, they estimate that even in the September quarter of 2020 (ie straight after the first and longest severe lockdown) the output gap was (barely) positive. And in the real world monetary policy actions (starting from late March) just don’t have such large and immediate real effects as to have made a big difference to activity as soon as mid-August (ie halfway through the September quarter). With hindsight – albeit only with hindsight – monetary policy choices, including the LSAP if it had real effects, were driving the economy further away from a balanced position (ie into a substantially positive output gap, now estimated to have peaked at almost 4 per cent of GDP, and the associated surge in core inflation).

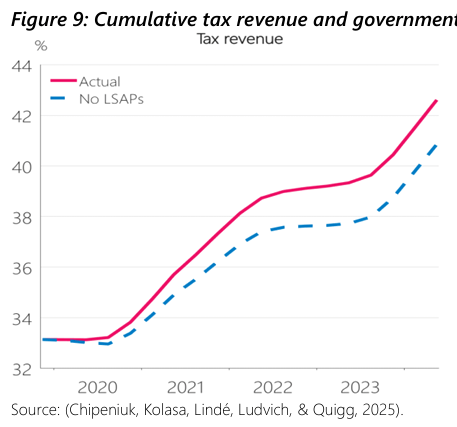

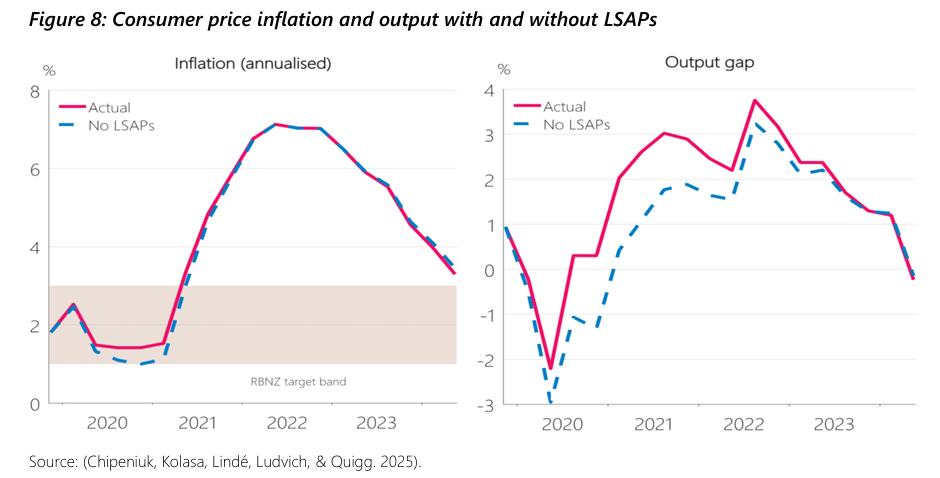

And this is where the Bank’s package last week gets borderline dishonest. Conway uses this chart

which a casual reader might think was all gain. But the chart ends just around the point where the output gap crosses into negative territory, and thus completely – and deliberately (we must assert for a senior policymaker) – ignores the more recent period, in which the Bank estimates that we are now in a materially negative output gap, and will in time have had three years of a negative output gap (ie GDP tracking below potential, with government tax revenue consequences). Pretty much all observers ascribe that negative output gap to the necessary working off of the earlier, marked, RB-allowed/enabled overheating (ie dealing with the inflation). Any honest reckoning of the fiscal consequences needs to take into account the entire period. There probably were some fiscal gains from the Bank’s monetary policy choices – surprise inflation reduced the real debt burden, and resulting fiscal drag picked up some extra revenue – but I doubt the Bank really wants to claim credit for that inflation they weren’t supposed to be aiming for and did not forecast.

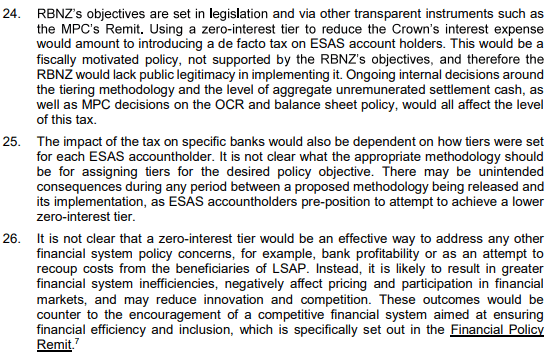

Most likely, over the full period, there were modest – but largely unsought and undesired – revenue gains (achievable, see above, with conventional instruments if only the Bank had done its preparatory job – and for central banks, like airport fire brigades, preparation for crises is a core part of the job), but large and easily identifiable losses from the risky punt made on the LSAP.

But all that assumes that the LSAPs made a material difference at all. That has long seemed quite unlikely to me. You can – as the Bank and IMF staff have done – construct a stylised model in which the LSAP makes a material difference, but that model doesn’t really seem to fit very well what was going on, here and abroad, and the LSAP simply isn’t necessary to explain almost everything that did go on.

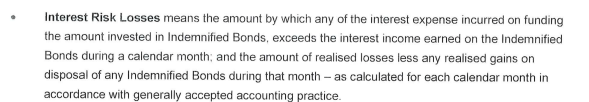

To be clear, I think most economists will agree that if the LSAP worked it wasn’t as (in the Herald’s unfortunate term) “money-printing”. The volume of settlement cash created – all reimbursed at the OCR – was simply not a material channel. If the LSAP made a difference it did so by one of two (perhaps mutually reinforcing) mechanisms: altering market interest rates in ways that had macro consequences (this is the Reserve Bank’s own story going back to 2020), and/or reinforcing market convictions/views that the OCR will be kept extraordinarily low for a protracted period.

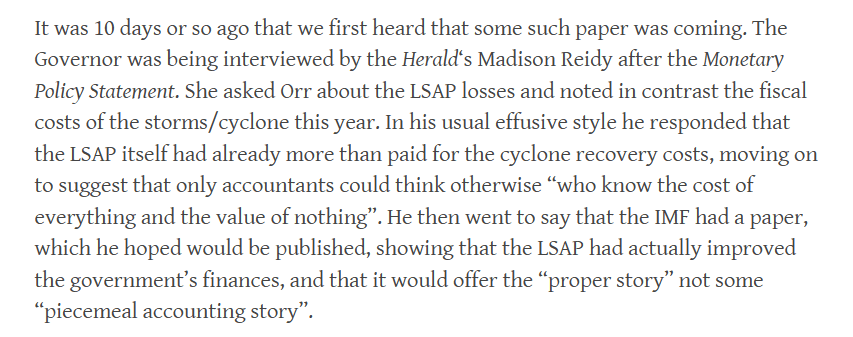

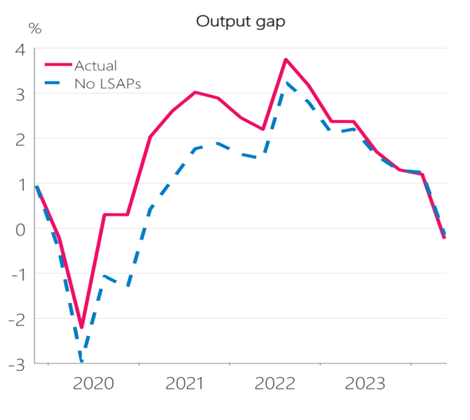

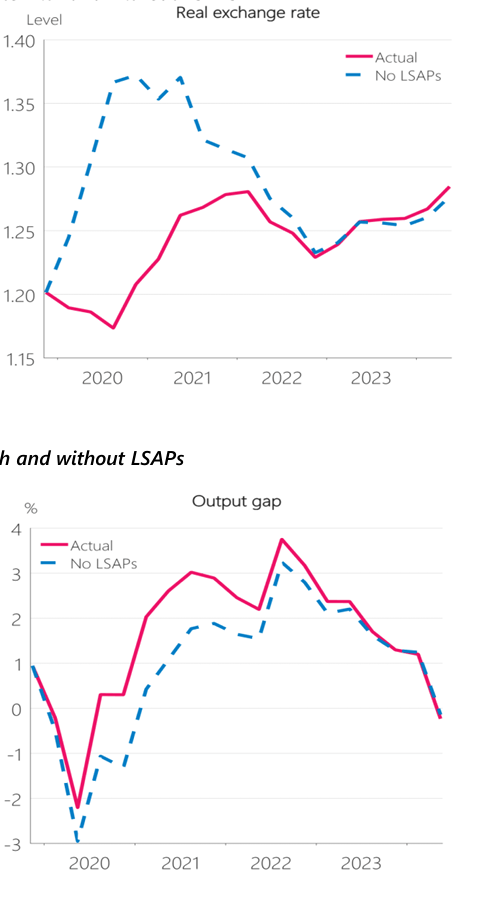

This is from the model Conway hung his hat on, in which he

cites the modelling exercise – not an empirical estimation but a stylised representation – in which the choice not to use the LSAP (in New Zealand) makes at peak about 150 basis points of difference to long-term government bond rates (relative to the counterfactual in which only the actual OCR cut was done) and a 20 per cent difference to the exchange rate. In this modelling exercise we are told that most of the work is being done by the exchange rate adjustment (itself responding to changing interest rate differentials), noting that long-term interest rates themselves aren’t a material part of the New Zealand domestic transmission mechanism.

But we are also told that the LSAP was roughly equivalent in its economic impacts to a 100 basis points cut in the OCR. And we’ve had plenty of swings in the relative policy rate spreads of 100 basis points or more (including since 2021) and none of them has resulted in a 20 per cent change in our exchange rate (which has been astonishingly stable over the last 15 years or so).

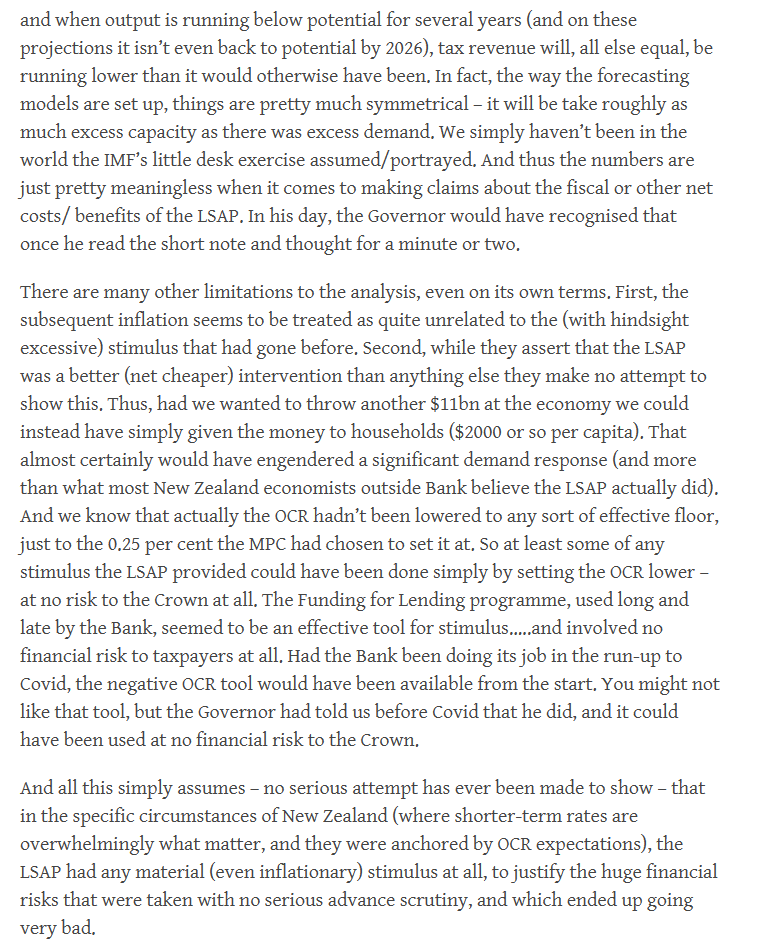

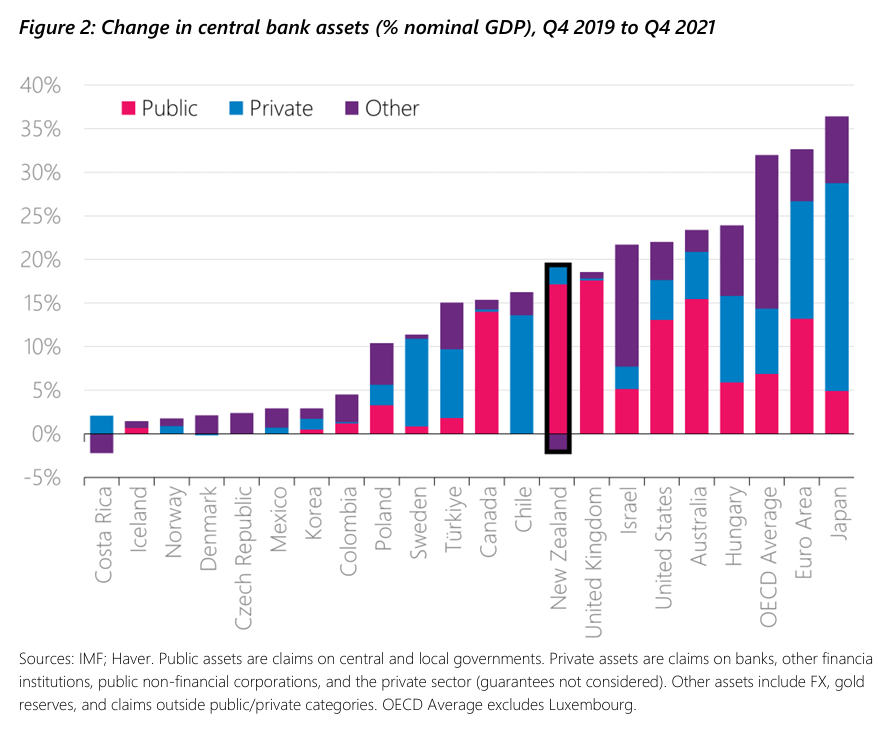

Another chart from Conway’s speech is this

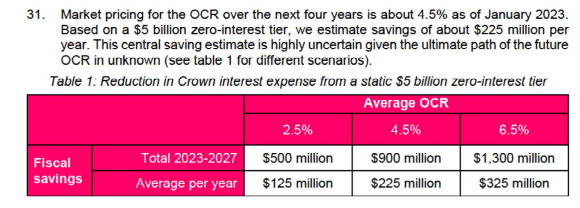

where you’ll see (red bars) that New Zealand’s use of government bond purchases was one of the largest among advanced countries (similar to the UK and Canada). But you will also see quite a group of countries to the left of the chart that seem to have done little or no QE over this period. Korea, for example, also cuts its policy rate by 75 basis points, but is there any sign of its real exchange rate rocketing upwards because they did no QE? Well, no. And one can run through the other countries and you will search in vain for such large effects (and yes each country has its own idiosyncrasies). Australia did no material QE until the end of 2020 (for much of the year they relied on policy rate cuts and an announced target for a three year rate) and there isn’t any sign of the AUD appreciating sharply against the NZD (where our central bank was actively pursuing QE).

And there are similar problems with the long-term bond yield story. Eyeballing that chart Conway cited, you’d have to think that advanced countries that did no little or QE in government bonds would have seen their long-term government bond yields rise sharply (and, to be clear, the New Zealand OCR was about middle of the pack for how much advanced country central banks cut in 2020). But again, evidence of such effects is sparse indeed. Take Korea again, their long-term bond yields didn’t fall as much as New Zealand’s did, but they certainly didn’t rise in 2020. Nor did Norway’s or Iceland’s – or, indeed, any advanced country. I don’t find it implausible that the scale of New Zealand’s LSAP might have made a bit of difference to longer-term bond rates, but eyeballing the cross-country experiences something like 20-40 basis points looks more plausible – eg our long-term bond rate did fall more than Australia’s in mid 2020.

And that is for a 10 year bond. What matters in the domestic economy is mostly 1 and 2 year rates (including through the mortgage lending and refinancing channel). And so the important question is likely to be whether the LSAP did anything much – directly or by signalling reinforcement effects – to affect those short-term rates. And there I think champions of the effect of the policy will find themselves on the backfoot. Those shorter-term bond and swap rates certainly fell very low (some were briefly slightly negative for a few weeks around September 2020, although by the end of 2020 all the short-term bond yields were at or above the 25 basis points that was then the OCR), but is there good reason to suppose those rates would have been much different absent the LSAP (or with an LSAP brought to an end in say December 2020)?

What else was going on? By late 2020 the Reserve Bank told us the operational issues around negative rates had been sorted out. In the Survey of Expectations (semi-expert respondents), the December quarter survey remarkably – looking back now – had the mean expectation for the OCR a year ahead at -0.16 per cent (with inflation two years out nonetheless still expected to well undershoot the midpoint). The MPC itself had pledged back in March 2020 (rashly) not to change the OCR for a year. And what of the Bank’s own forecasts? With all the stimulus already built in the Bank in the November 2020 MPS was projecting that inflation would stay at or marginally below the bottom of the target range through 2021 and 2022, and that the output gap would remain deeply negative at least through all of 2021. The Bank published “unconstrained OCR” numbers – where the OCR would go if deeply negative OCRs were possible, to get inflation back towards target – getting down to -1.5 per cent by the end of 2021. The fact that those forecasts and expectations were deeply wrong – as we know now – is irrelevant to the fact that that was the air people were breathing (and markets were trading) in late 2020. The prospect of any rise in the OCR any time soon seemed remote, and cuts couldn’t be ruled out (remember that only the MPC pledge to March 2021 had ever prevented the OCR being cut to at least zero).

Is it plausible that the LSAP had some effect on these rates? Well, perhaps. I wouldn’t quibble if someone was suggesting 20 or 30 basis points but…..short-term rates were always going to be much more heavily influenced by expectations of future OCR moves, and – independent of any LSAP announcements – the macro forecasts at the time were very very weak (as actually they were in Australia – check the RBA November 2020 inflation projections).

What of the stylised modelling results themselves? Well, I’d take them with a considerable pinch of salt. You might have hoped that someone in the Reserve Bank with an instinctive feel for NZ business cycles etc (surely there are still one or two of them) might have interjected and asked at some point how it was that this model posited near-instantaneous real economic effects from a change in the real exchange rate (the usual stylised view has been that those lags are particularly long, longer than those for interest rate effecs)

Or someone might have asked how it was – so very convenient – that the model produces only helpful effects on inflation from the LSAP (with no LSAP and a higher exchange rate perhaps direct price effects hold up inflation in 2020), and no unhelpful ones, despite the large positive impact on the output gap. And, as a reminder, it is the standard view that the real economic effects of monetary policy take more like 6-8 quarters to be substantially seen in inflation. If the LSAP made a real and material difference, it should have made one also to inflation – exacerbating the problems – in mid-late 2021, but this exercise somehow manages to tidy away any such effect.

Who can know quite what is driving the people at the top of the Reserve Bank. Perhaps they genuinely believe all this stuff, but I guess if you’d been a prominent part in the loss to taxpayers of getting on for $11 billion you’d have a fairly strong incentive to convince yourself it had all really been worthwhile. And I guess with the current more-moderate personalities at least we’ve moved on from those claims Orr used to make that the benefits had actually been multiples of the cost.

But whatever now drives them, these are lessons I think you should take away:

- had the Bank done its basic crisis preparedness job in the years leading up to Covid, LSAP would probably never have been deployed at all (or used only on a much smaller and briefer scale – the Bank also likes to claim they helped settle markets in late March 2020 although the evidence suggests any effect was small and entirely incidental to the Fed addressing problems at source). Orr’s instincts on preferred policy instruments (effective and with much lower financial risk) were correct,

- ultimately the major failure was a forecasting one. On the path of forecasts as they were in 2020, 2021 and early 2022, the Bank would still have wanted to be providing lots of monetary policy stimulus for a long time (that is what forecasts of very low inflation and large negative output gaps tell central banks to do – and contrary to Conway’s claim, this had nothing to do with the 2019-2023 specification of the Bank’s target; it would be the same today). Thus, the path of inflation would have been very much as we actually experienced it.

- but at least if we were going to experience the consequences of a major macro forecasting failure, the taxpayer wouldn’t have been facing almost $11 billion of losses in addition (to the inflation and the dislocation, still being experienced, in getting rid of it).

- responsibility for the substance rests with those in office over 2019-2021 (Orr, Hawkesby, Bascand primarily – and the rest of the then MPC)

- responsibility for the spin now rests with Hawkesby, Conway, and (presumably) Silk. Who knows if the rest of the MPC even saw this stuff before it went out. It would be interesting to hear perspectives from some of them – not involved over 2019 to 2021.

Finally, in fairness one might note that central banks generally have not been great at acknowledging failure and mis-steps. But being in bad company really is no defence. Recall that the quid pro quo for central bank operating autonomy was supposed to be serious transparency and accountability, built on demonstrable expertise. All appear to have been lacking at 2 The Terrace.