Sometimes it can be hard to keep up with the flow of pro-immigration articles in the Herald. At the moment of course, even they tend to be written with a defensive, more than celebratory, stance.

On Monday, the academic sociologist, Paul Spoonley – who leads CaDDANZ the MBIE-funded academic immigration advocacy and research programme – was out with a piece headed Xenophobia not welcome in migrant debate. Hard to disagree with that. Of course, not all fears are irrational, and political debate rarely occurs at the rarefied level of the fabled academic seminar room, but “deep-rooted fear towards foreigners” (the OED definition) doesn’t seem a particularly good basis for New Zealand’s immigration debate. But what was a bit puzzling when I read the article, and then re-read it, was that Professor Spoonley offered no evidence that “xenophobia” was what was at work here. And that’s good. Presumably if there was such evidence he’d have mentioned it.

And despite generally being a champion of New Zealand’s non-citizen immigration policy, Spoonley himself has come to the conclusion that current immigration levels are “unsustainable” and some changes are needed. Presumably he didn’t reach that conclusion based on “xenophobia”?

As it happens, most of the proposals he puts forward are pretty mild, or not even policies at all.

There is a case for revising aspects of the recruitment and approval of immigrants. The low value courses and qualifications offered by some educational providers puts New Zealand’s reputation at risk.

One could add that it is, in effect, an industry granted big export subsidies. We’d sell more of any specific good or service, if doing so came attached with work rights or residence points. Curiously, export education isn’t even that successful a subsidised industry. The total number of people granted student visas in 2015/16 was only around 4 per cent higher than at the previous peak in 2002/03.

A more proactive regional focus. Canada and Australia allow regions to set their own targets and to recruit the skilled immigrants needed locally – without undermining local workers or wages. Up to a third of the points required for approval for permanent residence can be granted by regions.

This is even more daft, and dangerous, than the existing (quality-diluting) policy of giving additional points to people with jobs outside Auckland. And since most local councils can’t even do well stuff they are already responsible for – not making urban land unaffordable – I’m not sure I’d want to trust them with immigration policy.

Social cohesion. Positive settlement outcomes for both immigrants and host communities would benefit from a greater investment in helping transition immigrants to life in New Zealand – more generous provisions for English language acquisition, for example, would help.

Of course, we could spend even more taxpayers’ money, or we could simply require that people settling here – refugees aside – actually speak pretty good English. These days, most really highly-skilled people – the ones we might actually benefit from – do.

And his final proposal

Let’s have a debate about population – its growth and distribution – as a context for decisions about immigration. And let’s not see immigration as a single causal factor or as a simple solution.

This is rhetoric rather than policy, but by all means have the debate. I’m pretty wary of “population policy” myself, but some serious study of whether policy-driven rapid population growth over most of the period since World War Two has helped lift the material living standards of New Zealanders, or productivity in the New Zealand economy, would be a worthwhile subject for academic researchers.

In the end, Spoonley is mostly playing distraction. He flings around the charge of “xenophobia,” without any substantiation, and then his own suggestions would make little useful difference in responding to the economic challenges, except by some tightening of rules around student visas (something the government has not yet addressed at all).

But the column that really grabbed my attention was one from the Herald business editor Liam Dann, headed Let’s lead the world on immigration debate. A worthy aspiration no doubt. But not, unfortunately, one the column contributed to. Instead, it is riddled with questionable claims and false comparisons, and at one point represents another example – this time not from a government minister but from an acolyte – of just making things up.

There is the weird opening.

It looks like immigration is going to be a big election issue.

That’s a shame.

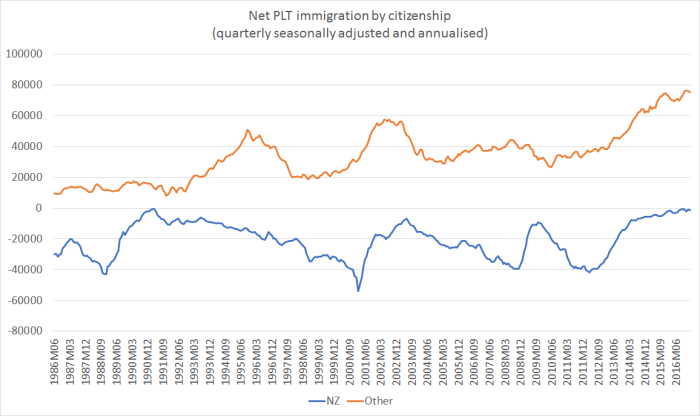

He doesn’t like the way the debate has occurred in some other countries, so seems to think we should take some sort of self-denying ordinance, and not debate one of the larger government economic and social policy interventions there is. Non-citizen immigration is, after all, far bigger here than in the UK, the US, or France. Has been for a long time.

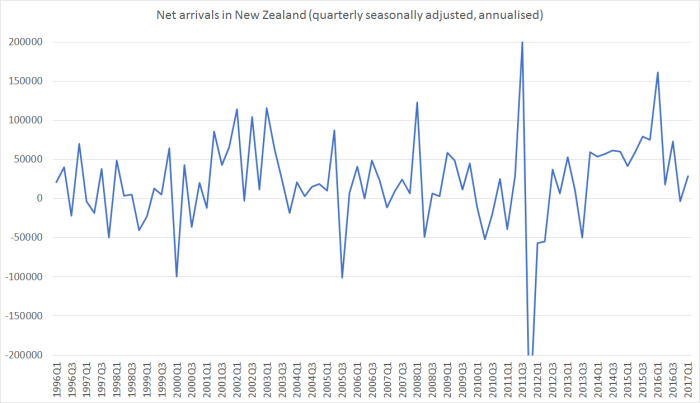

There have been a series of record highs for about a year. The numbers exceed even the great colonial influx into New Zealand in the 19th century.

On a per capita basis they exceed what the UK was experiencing pre-Brexit.

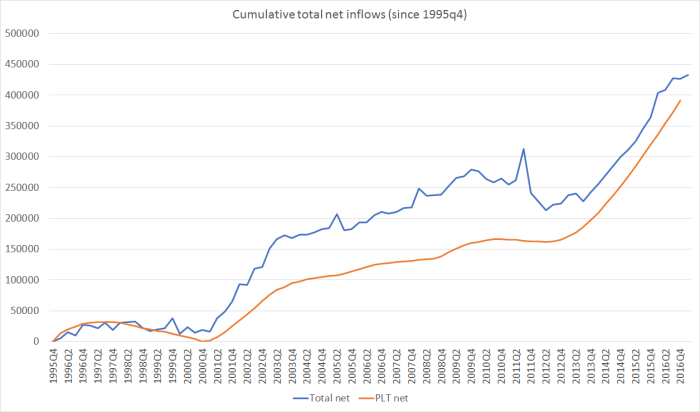

This is all rather misleading. Considered per capita, the net inflow over the last year (New Zealander and non-citizens) hasn’t even exceeded levels seen 15 years ago, let alone at the peaks in the 19th century. And, by contrast, every single year the number of non-citizens we let in far exceeds (per capita) the inflows to the UK. So the analytical and policy issues shouldn’t be about this year’s PLT flow, but about the numbers (and terms on which) we allow non-citizens to settle and/or work here.

According to Dann

So we are vulnerable to populist political hijack.

Any world-leading debate on these topics would recognise that the essentials of our immigration policy haven’t changed much for 20 years at least. Broadly speaking, we moved back to being a high (non-citizen) immigration country in the early 1990s.

I’m not even sure what “populist political hijack” really means, other “than some politician I really don’t like, responding to an issue of real public concern”. Sounds like democracy to me, messy as it often is.

Funnily enough, Dann also thinks there are some real issues that need addressing.

Immigration policy of the past decade is not sustainable. Our infrastructure is under pressure and we are woefully behind in building to catch up. That’s not the fault of immigrants, of course. It is the fault of politicians and voters.

Not sure how this is all the fault of voters. We were never asked if we wanted to have record rates of population growth, even though those in office knew that (say) the urban land markets were dysfunctional etc, so that importing lots of new people was only likely to exacerbate house price problems.

And, of course, the issues aren’t just about house prices or road congestion. There is the small matter of the continuing poor productivity growth in New Zealand (none in the last five years), the shrinking (as a share of GDP) export sector, or the realities of living in a country at the ends of the earth where, for 40 years (with cyclical ups and downs) the natives have been leaving, pursuing better opportunities abroad. Oh, and the highly misleading descriptions of the immigration programme – we’ve repeatedly been told it was a skills-focused programme, helping lift productivity etc, and now MBIE’s own numbers show than more than more than half those applying for residence don’t have skills that command even $49000 per annum in the New Zealand labour market.

Dann continues

In other words, it’s our fault. We have been trying to have our cake and eat it too.

No, it isn’t “our” fault. Voters didn’t ask for this. Political leaders – from both sides, but National is now in office – made it happen. And there is no “cake” for New Zealanders as a whole, only some nasty sectoral redistributions, and an overall economic performance that continues to underwhelm. But apparently

One thing lost in the immigration debate at the moment is how successful the policies have been for New Zealand.

Really?

Economically, we have outshone our international peers. We have skipped the economic pain that most of the world felt after the global financial crisis.

That’s not all down to immigration but it has played a big part.

This is just making stuff up. As I showed yesterday, we’ve done no better than the United States, which was the epicentre of the crisis – and that despite having about three times the rate of legal immigration the US has (and other bonuses like a record average terms of trade). We had a nasty recession, that took a long time to recover from – and actually immigration policy in the “bust” period wasn’t materially different than it had been in the earlier “boom”. We’ve underperformed Australia too.

Sure, there are places that are worse still – much of the euro area most notably – but there is just nothing to back this claim that we have “outshone our peers”, let alone that immigration policy has enabled us thus to shine. Saying it often enough won’t make it true. In fact, sometimes reality breaks through and even Dann seems embarrassed about channelling this stuff.

When you crunch the numbers on per capita GDP growth it has been far less flash.

Indeed. And it is things like per capita income growth and productivity growth that count. Even on the labour market side of things, the SNZ release this morning shows that most of the OECD countries that control their own monetary policy have lower unemployment rates than we do.

Culturally, too, New Zealand has grabbed global attention in a way unimaginable a generation ago.

This country used to be largely unknown outside the Commonwealth, where we were acknowledged as a backward British colony that was good at sport and had lots of sheep.

Since we still hold the record low test cricket score, racked up in the bad old days when we had some of the very highest material living standards in the world, I’m not even sure about that “good at sport”.

But, frankly, what is he talking about?

100 years ago, before the First World War, people flocked here – and not just from the Commonwealth – to study New Zealand’s economic and social reforms. And they often marvelled at what had been created, so quickly, so far from the centres of the world ( including (but not limited to) the best material living standards in the world).

Actually, 30 years ago, before the great immigration resumed, people abroad were fascinated by New Zealand’s economic reforms. It was a darker story by then, trying to pull back from decades of decline, but the interest was real nonetheless.

Does anyone remember Dame Edna’s tragic Kiwi bridesmaid Madge Allsop? She summed up our image pretty well.

Personally, I don’t remember this character, but I’m sure Dann isn’t trying to suggest that Australians have stopped making fun of New Zealanders (accent and all), or vice versa.

So what is he talking about? Does he know? Allegedly….

Against all odds, New Zealand became cool.

Where is the evidence? What does “cool” mean in this context? And what does it do, even if it is true, for the living standards of ordinary New Zealanders? Dann doesn’t tell us. And yet somehow

Our place in the world has changed and that warrants debate about the immigration policy settings we have in place.

Actually, if one takes any sort of longer view of modern New Zealand history, our place in the world is in decline. That is more or less inevitable. We were once one of the handful of (very successful) offshoots of the most powerful empire in the world. 100 years ago there weren’t many independent countries, and few as successful as we were. Since then, many more countries have emerged, and quite a few have got a lot richer. The UK’s global position has declined, and even the US is no longer what it was (in say the decades from 1940). We are neither powerful nor important – no longer with automatic access to counsels of the great and powerful we once had – and, worse, we aren’t even that successful economically any more. That has real implications for our own people, especially the poorer of them.

So, I really have no idea what Dann is on about. Perhaps he is thinking of some references in once-hip publications like Lonely Planet guides? But to what end? As I ‘ve shown previously, our exports of services – the lure of tourism, export education etc – are lower now as a share of GDP than it was 15 years ago, in an age when international trade in services globally has become ever more important.

Leaving aside the detached-from-reality rhetoric, Dann tries to come back to specifics

The Government has belatedly started to recognised that with policy tweaks that have not yet had time to show results.

We could go further and look at more fundamental changes – such as how we set the criteria for residency.

But it would be a terrible thing for the debate to play out here the way it has in other parts of the world.

Quite what does that mean? You might approve or disapprove of the Brexit result (I approve), but the process was an open one, there were no riots on the streets, and views differ on quite how large a role immigration policy played anyway.

I reckon Donald Trump is fundamentally ill-equipped to be US President. Then again, the choice was a poor one. I couldn’t have voted for him or his principal opponent. And is a physical wall a good solution? Quite probably not. But it was an open and democratic election, and there were plenty of other issues at play in the election. And – unlike us – the US really does have a large stock of illegal migrants in the country.

Alternatively, and optimistically, New Zealand is in a position to lead the world on the immigration debate. We could do this right.

But simply flinging around, as slurs, references to Brexit or Trump isn’t really a great start to the sort of debate Dann claims to want to have in New Zealand. After all, if immigration is an issue in those countries, there are good reasons why it could be a much bigger issue here (we simply take more people, per capita).

We could pay close attention to the data, we could look at economic impact studies and we could have a frank and open discussion about the kind of country we want to build.

That would certainly be a novel (but welcome) approach. Perhaps Dann could point us to the New Zealand specific studies illustrating how New Zealanders, and New Zealand productivity levels, have been raised by decades of large scale immigration, much of it simply not that skilled? Other champions of immigration policy haven’t been able to. There is plenty of theory, but not much grounded analysis that takes specific and detailed account of the circumstances of New Zealand.

Dann doesn’t like the idea of Labour promising to do something to markedly cut the non-citizen immigration flow.

It is difficult for Labour because the politics are polarising. Labour wants power, it sees a rich vein of discontent but in the current topsy-turvy political environment, it has to make careful choices.

Retaining a traditional, optimistic liberal view leans towards free and open borders. That now puts them on the side of the neo-liberal globalists – not a fashionable place for the centre-left these days.

But campaigning to radically slash immigrant numbers by unspecified amounts puts them in the camp of angry nationalists like Winston Peters, Donald Trump and Nigel Farage.

It would certainly be good to see some specifics from Labour – it is after all only four and half months until the election. But it is not as if Labour has always been some sort of “open borders” party. It was the Labour icon, Norman Kirk, who in the 1970s put in place the biggest post-war adjustment to immigration policy, depriving people from the United Kingdom (then far and away the main source country) of their automatic right to move here.

For the last few decades, Labour and National have had much the same immigration policy – believers, apparently, in the rhetoric of lifting productivity through immigration, and in the skill shortages, that never seem to ease no matter how many decades we wait.

Suggesting that Labour would cut immigration by tens of thousands certainly needs something concrete behind it – and soon – but I’m afraid that comparisons between Andrew Little (or Jacinda Ardern, Grant Robertson, David Parker and Phil Twyford) and Donald Trump simply aren’t worthy of a serious journalist, and especially not one making the high-minded call for a world-leading immigration debate.

Dann starts to come to the end of his column

We can’t let the politics become emotive. This is fundamentally about economics. It should be boring.

Not sure I entirely agree. Politics is about conflicting world views and values. There are, and inevitably will be, emotional dimensions about that. Personally, I’m angry at the decades of failure by a succession of political leaders to really grapple with New Zealand’s economic underperformance. And pretty upset about the apparent (practical) indifference to the housing disaster, all politically wrought. But Dann asks

Can we quantify how much value immigrants add to the economy?

How does the added value compare with the economic cost of new infrastructure that we need to cope with increased population?

It isn’t really a fiscal question, but the honest answer to his first question is that “no, no one really has”. It has been a programme based on faith and theory, and often the short-term self-interest of employers (especially those in the non-tradables sector). The government does not know if large-scale immigration has added to New Zealand’s productivity over time. For such a large experiment, that is an extraordinary failure.

Distributional issues matter.

The harder question is trying to understand how the value and costs are distributed.

Some established citizens will be bigger beneficiaries than others. There are different geographic impacts.

Given we’ve had an immigration policy that favours wealthy immigrants it is self-fulfilling that our policies have increased wealth in this country.

But they may also have exacerbated inequality

Again, he has lost me. Most of our immigrants aren’t very skilled or wealthy at all – most can’t even earn $49000 a year, the starting salary for a primary teacher with a basic degree. So there is no automatic presumption that the country is wealthier as a result (again, per capita, the only measure that really counts). And it shouldn’t really be news to the business editor of our largest-circulation paper that inequality hasn’t materially changed in New Zealand in the last couple of decades (at least if the distorted housing market is excluded). The New Zealand Initiative, rightly, point it out repeatedly.

I’m all for a good quality debate about New Zealand’s immigration policy. One is certainly well overdue. But when Dann’s call for such a debate is so riddled with errors, misconceptions, and slurs, it is hardly a good start. In the end, it is hard to avoid a conclusion that what Dann really wants is just a continuation of the status quo, with a few more houses and roads built, and the column is mostly an attempt to avoid the real debates. It certainly isn’t the start of a world-leading debate, especially not one that engages seriously with the decades of serious economic performance, or with the revealed choices of New Zealanders – for 40 years now – to leave.