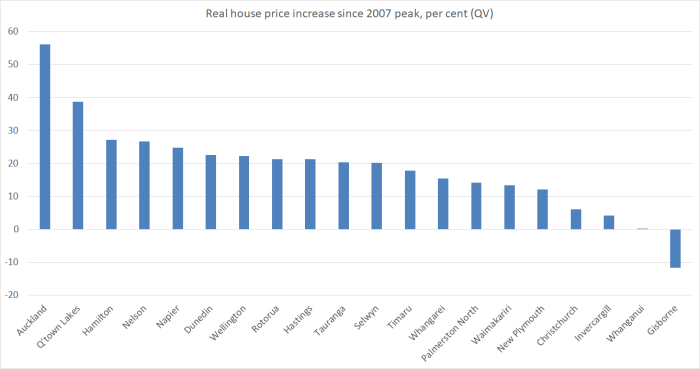

There was a strange editorial in the Listener this week, lamenting what they see as New Zealanders’ mania for consumption spending. The editorial starts from the fact that the proportion of New Zealanders reaching age 65 mortgage-free has been in decline, and goes off half-cocked from there. There is no mention at all, for example, of the other important fact that New Zealand real house prices have risen very sharply and are now, relative to incomes, some of the most expensive in the world. You would expect that would change the distribution of indebtedness and make it more likely that more old people would still have debt (as well as an artificially more valuable, not very liquid, asset).

But whoever wrote the editorial is convinced that the problem is consumption.

“We’ve felt freer to upgrade the car, have a holiday or renovate using debt rather than savings”

“Loans have seemed so affordable, and consumer goods so increasingly accessible, that the “on-the-house” habit has done further damage to the economy. It has three highly undesirable featires: low to stalled productivity, very low income growth and consumptive spending bounding ahead.”

“…a more deep-seated problem than our failure to tax capital gains. It’s about how we’re spending – and perhaps more importanyly, why we’re spending. The internet has made every product imaginable deliverable to our doors – amped up by such marketing constructs as Black Friday – and ambient anxiety-fuelling over “not missing out” at Easter, Christmas, Halloween and the like have stoked our spending to ever higher records.”

and so on.

But it is, pretty much, a fact-free zone.

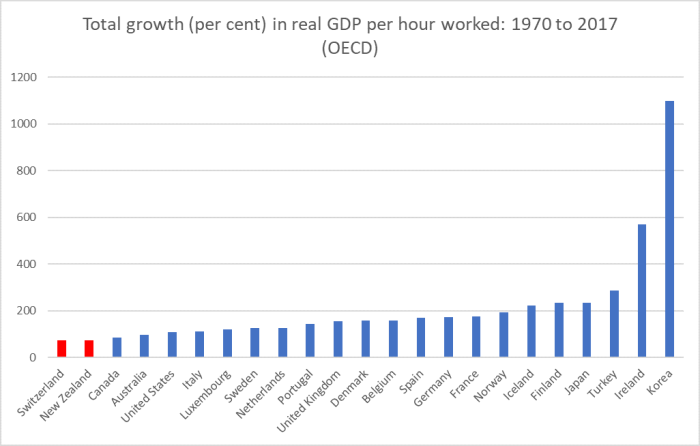

It shouldn’t be surprising that (real) spending is higher than it used to be and that people are buying more stuff. We have higher incomes than we used to have. Yes, I bang on more than most about the failure of policy here and weak productivity growth, but real per capita GDP is now about 90 per cent higher than it was in 1970. All else equal, one might expect the typical New Zealander to be consuming a lot more stuff (goods and services) – they can afford to.

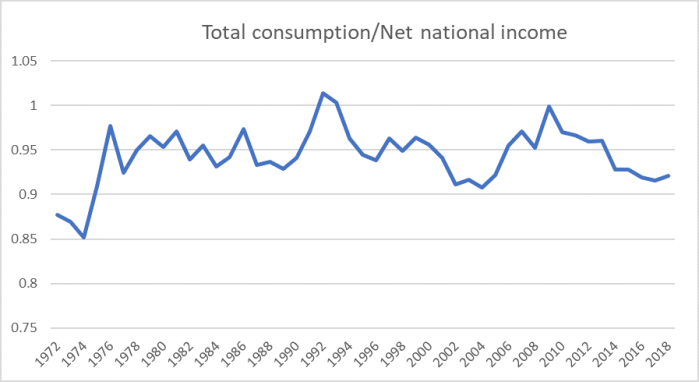

And how has consumption spending tracked relative to income? This chart shows all consumption (public and private) as a share of net national income. Net national income is the measure of how much income residents of New Zealand have available to spend: relative to GDP, it subtracts the bit of New Zealand production that actually accrues to foreigners (well, non-residents), and also subtracts an allowance for depreciation (some of gross earnings needs to be spent on just maintaining/replacing the capital stock that helps generate the income). To believe the Listener story, the line should be trending upwards, perhaps especially since the financial system was liberalised in the mid 1980s.

It doesn’t of course. The trend has been dead-flat for decades now. There is some cyclical variability – those last two peaks were the years of serious recessions (March years 1992 and 2009) – since consumption spending tends to be more stable than national income. Fiscal policy makes a difference too: when governments are running big surpluses (as in the early 00s) the consumption share of income tends to be temporarily subdued. On the other hand, there is no sign that, in aggregate, financial liberalisation made any material difference. Markedly higher house prices haven’t either – which shouldn’t really be surprising, as for every person who feels a bit wealthier, there is another for whom home purchase is that much further off.

And there just is no story, able to be defended from the data, about New Zealanders in aggregate on a consumption splurge. Sure our savings rates are modest by international standards, but they’ve been so for a long long time. And, to repeat, consumption is consistently less than income (see chart). Mr Micawber would approve

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen [pounds] nineteen [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

That long-term chart used total consumption (public and private). For many purposes that is the right metric to use: there is a considerable degree of substitutability between government consumption and private consumption. (And if, for example, the government gave you a voucher to pay for your kids’ schooling redeemable only at the local state school, the resulting education services would probably be measured as private consumption rather than – as at present – government consumption. Nothing of substance would have changed, just the labelling).

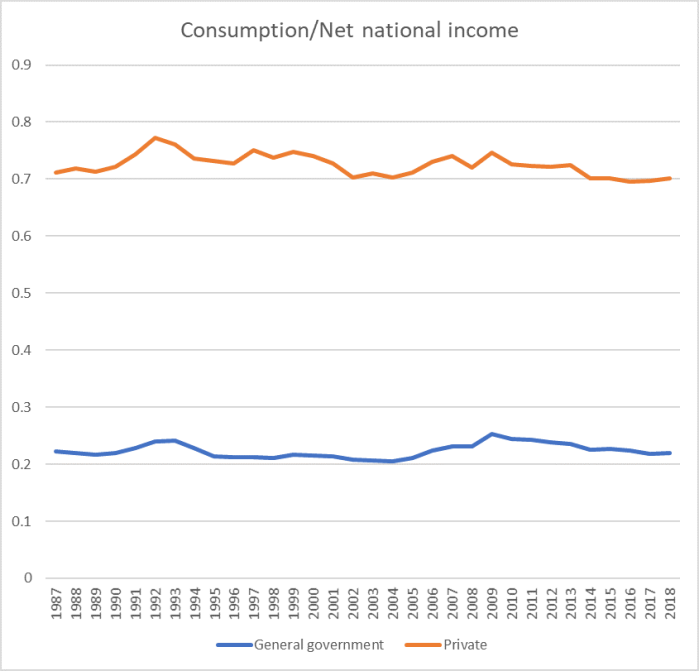

But there is a breakdown between public and private consumption going back as far as 1987. Here is that chart, with the components again shown as shares of net national income (March year annual data).

No trend (beyond “almost dead flat”). For what little it is worth, in the most recent year both public and private consumption spending were a touch below the respective 30 year averages.

The sad truth is that actual consumption in New Zealand is probably quite a bit lower than it should be. Back in 1970, real GDP per capita in New Zealand was about the same as that in Germany. These days, average GDP per capita in Germany is about 30 per cent higher than that in New Zealand (and hourly productivity is about 60 per cent higher). The Germans not only get to consume more stuff but (in economist-speak) to consume more leisure (hours worked per capita are much higher in New Zealand than in Germany). If we’d managed to match German economic performance, almost certainly the typical New Zealand household would be consuming more, not less. Quite possibly our average savings rate might be a bit higher too.

I’m a Puritan by upbringing and inclination and so when I read lines like this from the Listener editorial

“Popular TV home-renovation contests and “property porn” create a chronic sense of FOMO, with faddy edicts: one must refit one’s kitchen and bathroom every five years; last year’s wallpaper is now dated.”

I can nod along (even while wondering just how many people actually behave that way). Being Puritan by background, middle-aged, and male, the idea of “fast fashion” just seems weird. “Black Friday” is an alien import, and I buy books from (among other places) charity shops (rather than providing them – as the editorial puts it – with “unsaleable dumpings from nouveau declutterers”). But odd as some of these phenomena might be, they really don’t seem to add up to much in the aggregate consumption data.

There are big problems around the housing market, almost entirely the result of central and local government choices. We should worry – as the Listener does – about the growing share of people carrying debt into old-age, or never having been able to buy a house in the first place. But the issues have very little to do with some wholly-mythical national consumption splurge. And responsibility needs to be sheeted home to central and local governments, not to consumers trying to make the best of their, increasingly constrained, options.