The speech and Bulletin put out by the Reserve Bank yesterday made much of the importance of market discipline in the financial sector. The two documents have slightly different lists of conditions which the respective authors think make it more likely that market discipline will be effective, but a common element is “market participants [must] have incentives to monitor financial institutions”. Toby Fiennes argues that in the New Zealand context:

“some aspects of the regulatory framework, such as Open Bank Resolution (OBR) and no deposit insurance, reinforce these incentives.”

and O’Connor-Close and Austin, in the Bulletin, add in

“nor is there any policyholder protection scheme for insurance firm customers.”

This has been a longstanding view held by the Reserve Bank. I’ve long thought it was wrong.

Of course, if you were confident that, were a bank to fail in which you were holding deposits or other interest-bearing securities, you would lose money, and no one would bail you out, you would have quite a strong incentive to pay attention to the health of any institution in which you had a reasonable amount of money, and (to economise on monitoring costs) to hold your money, as far as possible, with those institutions generally regarded as safest.

Same goes for insurance. If you had your house insurance with an insurance company, and no one would bail you or it out if the company failed, you’d have quite an incentive to insure with companies that would prove resilient through the worst of shocks.

In the case of banks, OBR is designed to make it more technically feasible for political leaders to let major banks fail. In that model any losses (mostly) fall on the creditors, and yet the failed bank can quickly re-open, keeping the day-to-day flow of transactions and routine business credit operational. It is technically elegant system. But whether or not it is ever used is not up to the Reserve Bank. That is matter for whoever is Minister of Finance at the time – and no doubt the Prime Minister of the day too.

Suppose a big bank is on the brink of failure. Purely illustrative, let’s assume that one day some years hence the ANZ boards in New Zealand and Australia approach the respective governments and regulators, announcing “we are bust”.

Perhaps the Reserve Bank will favour adopting OBR for the New Zealand subsidiary (since the parent is also failing they can’t get the parent to stump up more capital to solve the problem that way). But why would the Minister of Finance agree?

First, Australia doesn’t have a system like OBR and no one I’m aware of thinks it is remotely likely that an Australia government would simply let one of their big banks fail. But in the very unlikely event they did, not only is there a statutory preference for Australian depositors over other creditors, but Australia has a deposit insurance scheme.

I’m not sure of the precise numbers, but as ANZ is our largest bank, perhaps a third of all New Zealanders will have deposits at ANZ.

So, if the New Zealand Minister of Finance is considering using OBR he has to weigh up:

- the headlines, in which ANZ depositors in Australia would be protected, but ANZ depositors in New Zealand would immediately lose a large chunk of their money (an OBR ‘haircut’ of 30 per cent is perfectly plausible),

- and, even with OBR, it is generally accepted (it is mentioned in the Bulletin) that the government would need to guarantee all the remaining deposits of the failed bank (otherwise depositors would rationally remove those funds ASAP from the failed bank)

- and I’ve long thought it likely that once the remaining funds of the failed bank are guaranteed, the government might also have to guarantee the deposits of the other banks in the system. Banks rarely fail in isolation, and faced with the failure of a major banks, depositors might quite rationally prefer to shift their funds to the bank that now has the government guarantee.

And all this is before considering the huge pressure that would be likely to come on the New Zealand government, from the Australian government, to bail-out the combined ANZ group. The damage to the overall ANZ brand, from allowing one very subsidiary to fail, would be quite large. And Australian governments can play hardball.

So, the Minister of Finance (and PM) could apply OBR, but only by upsetting a huge number of voters (and voters’ families), upsetting the government of the foreign country most important to New Zealand, and still being left with large, fairly open-ended, guarantees on the books.

Or, they could simply write a cheque – perhaps in some (superficially) harmonious trans-Tasman deal to jointly bail out parent and subsidiary (the haggling would no doubt be quite acrimonious). After all, our government accounts are in pretty reasonable shape by international standards.

And the real losses – the bad loans – have already happened. It is just a question of who bears them. And if one third of the population is bearing them – in an institution that the Reserve Bank was supposed to have been supervising – well, why not just spread them over all taxpayers? And how reasonable is it to think that an 80 year pensioner, with $100000 in our largest bank, should have been expected to have been exercising more scrutiny and market discipline than our expert professional regulator (the Reserve Bank) succeeded in doing? Or so will go the argument – and it will get a lot of sympathy.

(There is provision in the OBR scheme for a “de minimis” amount below which the haircut might not apply. If the de minimis amount is, say, $500 – roughly a fortnightly New Zealand Superannuation amount for a couple – it is neither here nor there for the scheme as a whole. But a high de minimis amount looks a lot like ex post unfunded deposit insurance.)

Note that I’m not arguing that bailouts are “a good thing”, simply that having the OBR tool really does not dramatically alter the incentives politicians will face in dealing, at the time, with the imminent failure of a large bank. And rational investor know that. For the case of a large bank, OBR simply isn’t really a time-consistent strategy for politicians.

Some people at the Reserve Bank will accept the point, but argue that we still need OBR to have a credible weapon to wave in front of the Australians in a crisis. If they think New Zealand might just be “crazy” enough to use it, it might – so it is argued – help us negotiate a slightly less unfavourable bail-out deal. Perhaps. But Australians can read domestic politics too. I have no problem with having it in the toolkit – perhaps it could be useful for a small bank – but no one should pretend that it solves bail-out risks and restores retail market discipline, red of tooth and claw. And the probability of a bail-out, with a focus on protecting retail deposits, probably weakens market discipline at the margin even among wholesale investors.

And what are the precedents? 25 years ago the Bank of New Zealand was bailed out. Yes, the government was the largest shareholder at the time, but I didn’t detect any sense – at the very peak of the Douglas-Richardson era – that ownership determined whether the government of the day let the BNZ survive or fail.

More recently, the retail deposit guarantee scheme was put in place in late 2008 – not just for finance companies, but for the big banks too. The decision was made by the previous Labour government – but it was endorsed by the Key/English led Opposition, and was recommended (in substance if not in precise detail) by the Reserve Bank and Treasury. I wrote many of the papers.

And more recently still, AMI was bailed out – by the current government, on the recommendation of the Reserve Bank and Treasury.

In his speech, Fiennes note that

“it is of course true that many people expect governments to stand behind their deposits. That expectation was reinforced by the widespread Government guarantees (including in New Zealand) during the GFC. The existence of an expectation, though, is not a sound reason to adopt deposit insurance”.

That might be true if depositors had no leverage. But they do. It is called the ballot box, and politicians are very well aware of it.

If depositors, or policyholders, expect bailouts, and political leaders have incentives to respond to, and deliver on those expectations, then it may be a much less inferior option to adopt an explicit retail deposit insurance scheme upfront.

Deposit insurance need not be a substitute for OBR, but may actually make it a little more credible that OBR could be allowed to work. If there is a bail-out, it will benefit not just New Zealand retail depositors, but wholesale lenders too, domestic and foreign. There is likely to be much less political appetite for bailing out the wholesale creditors (especially the foreign ones), but a simple bailout does not enable one to distinguish. By contrast, a properly specified deposit insurance scheme enables one to be very clear upfront which deposits are likely to be covered, and which not – and to charge for that coverage accordingly. In event of a bank failure, OBR could be applied to all creditors, with the deposit insurance scheme “reimbursing” the retail depositors to the extent defined in the scheme. And in the event of a serious bank failure, the ability to impose loss on (particularly) foreign lenders (though in practice all wholesale creditors) is a net welfare gains to New Zealanders. Letting losses fall on New Zealand retail depositors might be reasonable economics, but (a) it probably doesn’t work politically, and (b) it simply transfers the losses from one set of New Zealanders to another.

Deposit insurance schemes are not ideal – and the Reserve Bank speech and article repeat some of the challenges. But bailouts are not ideal either, and experience suggests very strongly that bailouts remain the preferred default option at the point of crisis. As someone put it to me recently, in some sense if you don’t have an explicit limited deposit insurance scheme then, de facto, you have an implicit unlimited deposit insurance scheme (ie bailouts). And reasonable depositors will know it.

And if deposit insurance schemes aren’t ideal, they are fairly ubiquitous. As this recent IMF Working Paper points out (p32) every single advanced economy member of the IMF has an explicit deposit insurance scheme, with the exception of Israel, San Marino, and New Zealand. San Marino aside, every European country, advanced or emerging, has such a scheme, and Africa is the only continent where a majority of countries do not have such schemes. It has never been clear why the Reserve Bank thinks New Zealand can, or sensibly should, sustain being different, given the political economy pressures that all governments face.

And it is not as if deposit insurance has been withering since the financial crises of 2008/09. As the IMF paper illustrates, coverage has often been extended, and co-payments wound back.

I noted this morning that, for all its insistence on having regular private data that creditors can’t get access to, the Reserve Bank continues to assert that, in effect, it has no financial “skin in the game” – the risks are with creditors. In a second-best world, a deposit insurance scheme actually helps ensure that government agencies really do directly have skin in the game; financial risk if things go wrong. That might actually sharpen accountability.

It was really rather naughty, and unhelpful, of the Reserve Bank not to have devoted some space to the political economy pressures, and the New Zealand bailouts/guarantees to which they (and The Treasury) have been party. Of course, it might have been difficult to have done so, and would have undermined a good story, but it would have got us closer to better understanding the real choices and tradeoffs that societies face and make in this area, ex ante and ex post.

Of course, the decision on a deposit insurance scheme is not one for the Reserve Bank. It is a government decision, and one that would require legislation to implement. It is understandable that the current government feels badly burned by the cost of the guarantee of South Canterbury Finance. But given the incentives that governments will inevitably face if a major bank, or insurer, is on the brink of failure, it is surely time to shift direction, and put in place an explicit insurance scheme, for which depositors would be charged. Doing so would probably, overall, strengthen market disciplines a little, not weaken them as the Bank argues. Bailouts of all creditors might still happen – between Australian government pressure, and the threat of disrupted access to foreign funding markets – but at least (a) the government would have raised some revenue in advance of the costs, and (b) we would be able to have more rational, and emotionally (and politically) plausible, arguments about the reasonableness of allowing unsophisticated investors who had taken little or no obvious risk (deposits in one of our larger banks) to face large unanticipated losses.

At interest.co.nz, Gareth Vaughan recently had a nice piece also making the case for deposit insurance in New Zealand.

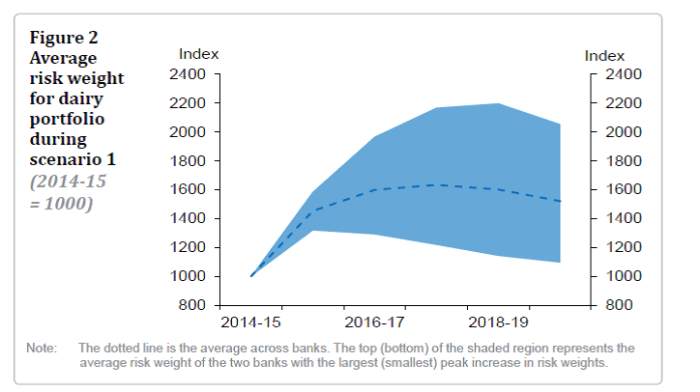

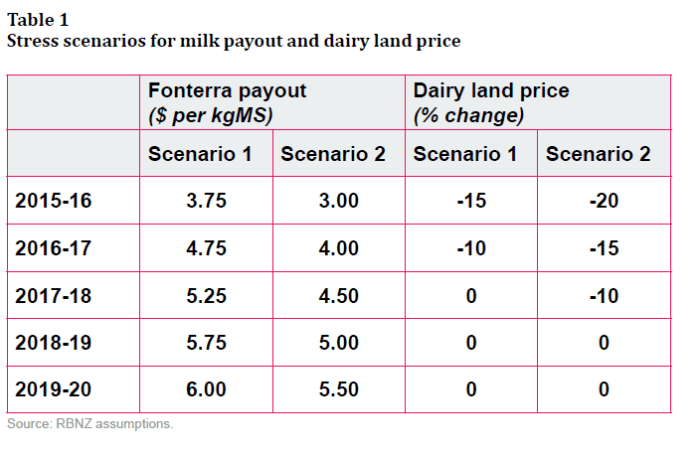

I’m largely going to ignore Scenario 1 from here on. As the long-term average real milk price is probably only around the assumed 2017/18 level, Scenario 1 doesn’t represent much of a stress test at all. The banks and the industry would have to be have been very rickety for a scenario like that to have presented a banking system problem. I think the Reserve Bank should also have discounted these results, rather than highlighting them in their press release.

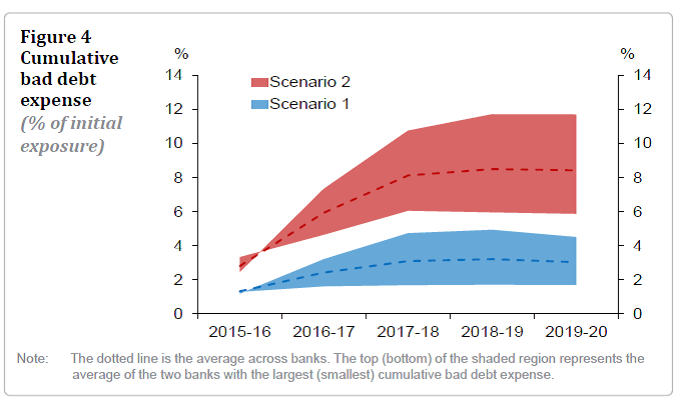

I’m largely going to ignore Scenario 1 from here on. As the long-term average real milk price is probably only around the assumed 2017/18 level, Scenario 1 doesn’t represent much of a stress test at all. The banks and the industry would have to be have been very rickety for a scenario like that to have presented a banking system problem. I think the Reserve Bank should also have discounted these results, rather than highlighting them in their press release. In a single year, dairy land prices fell by more than 30 per cent – and that was a severe, but very short-lived, fall in milk prices, and a rise in dairy non-performing loans that was still moderate compared to what we see in Scenario 2 in the current stress test. Perhaps deliberately, the Reserve Bank’s stress test does not seem to have taken account of a second round of selling (forced or voluntary), and the potential for that to drive land prices well below what might be a longer-term equilibrium level. Overshoots routinely happen in such markets, where liquidity is thin to non-existent, uncertainty is rampant, and potential buyers are few. As

In a single year, dairy land prices fell by more than 30 per cent – and that was a severe, but very short-lived, fall in milk prices, and a rise in dairy non-performing loans that was still moderate compared to what we see in Scenario 2 in the current stress test. Perhaps deliberately, the Reserve Bank’s stress test does not seem to have taken account of a second round of selling (forced or voluntary), and the potential for that to drive land prices well below what might be a longer-term equilibrium level. Overshoots routinely happen in such markets, where liquidity is thin to non-existent, uncertainty is rampant, and potential buyers are few. As