When our kids were little one of the books we often read them was “Bears in the Night” in which the young bears, hearing a noise outside, sneak out of the house at night, climb Spook Hill and then, terrified by the sudden appearance of an owl – not the most threatening of birds – whose call they’d heard, rush back to the comfort and security of home and bed.

It came to mind when reading some of the arguments being advanced by government officials and banks over the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Amendment Bill currently making its way through the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee.

The key controversial bit of the bill is the proposal to legislate retrospectively to close down class action suits currently before the courts against ANZ and ASB in respect of flaws in loan variation procedures etc that occurred between 2015 and 2019. The Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act had been amended in 2015 in ways that provided (MBIE’s words here) “that the borrower is not liable to pay interest or fees over any period of non-compliant disclosure made before loans are entered into or varied”. In late 2019 the Act was further amended so that for future breaches courts would have “explicit discretion to extinguish or reduce the effect of this provision in order to reach a just and equitable outcome”. That amendment was deliberately and consciously not made retrospective, but the current government now proposes to further amend the Act to apply the post-2019 regime to breaches that arose between 2015 and 2019.

Retrospective legislation is, almost without exception, an odious concept. Perhaps one might make an exception where, say, there was a clear typo in the legislation, giving a quite different meaning to the words of the legislation than Parliament had clearly intended. That wasn’t the case here. Rather, right or wrongly, Parliament changed its mind in 2019 about what the law should be going forward. Now the government – egged on by the banks – wants to make it as if a consciously and deliberately chosen law never was.

(Perhaps one might also make an exception to the general principle against retrospectivity if it was belatedly realised that the words Parliament had enacted enabled the strong to egregiously exploit the weak. I don’t know that that exception is in the typical lawyers’ list, but as a citizen/voter I could see the possibility (perhaps a parallel to exercise in criminal cases of a royal prerogative of mercy).)

What is puzzling is why the government would propose to amend the law retrospectively to help out large and highly profitable foreign banks. And in so doing to bypass what is apparently usually the practice when (as happens on rare occasions) retrospective legislation is passed, when cases already before the courts are (apparently) protected.

I hadn’t paid an awful lot of attention to the whole issue until two or three weeks ago when big scary numbers generated by the Reserve Bank were reported (eg here) and thus entered the public debate under headlines (not, to be clear, sourced to the Reserve Bank) about threats to the financial system unless this retrospective law was passed. $12.9 billion (the maximum estimate reported) sounded like a lot of money (but just glancing at articles I didn’t have a basis for knowing what a right number might actually be), even if stories about threats to the soundness of the financial system never rang true even for a minute.

And I still didn’t pay a lot of attention until the media reporting this week of the appearances before the select committee of the Bankers’ Association (strongly in support of the proposed amendment), the lawyers for the plaintiffs in the class action suits, and representatives of the litigation funders, LPF. The video of those appearances, and associated questions and answers, is currently here.

Yesterday, one of LPF’s representatives rang me, apparently given my name by several people as someone who might write a critical piece for them, especially on the Reserve Bank numbers, and the uses and abuses being made of them. I don’t really do submissions for hire, and am not taking any money from them, but my interest was piqued, and I benefited from a couple of useful conversations with them. More importantly, they sent me the document that contains the material from the Reserve Bank, a paper from MBIE to the then Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs (Andrew Bayly) from October last year which includes “Annex Two: Summary of RBNZ modelling and advice”. That annex appears to have been written by the Bank. The full document is here

MBIE Paper on CCCFA retrospectivity amendment 10 October 2024

Here is what there is on the estimates

In other words, we know nothing about the model, the scenarios, assumptions etc although it appears – from the OIA exclusion ground cited – that they must have obtained some data from one or other of the banks to somehow inform their numbers.

Note, though, that even the “big scary number” scenario, isn’t exactly a grave financial stability risk: “low to medium impact on capital ratios” is the Reserve Bank’s own line. Big numbers but if the underlying business models are profitable (as New Zealand banking typically is) then even in a hypothetical like this recapitalisation wouldn’t be expected to be an issue (whether from direct shareholder injections or retained earnings). Aside from anything else, and as they note, litigation will roll on for years. Losing on the scale of this “big scary number scenario” would be painful, but from the outside you could conceptualise it as a bit like a backward-looking windfall tax which, justified or not, wouldn’t normally really affect future behaviour. And when bureaucrats and the like come up with three scenarios, or three policy options, they typically expect people will be drawn to the middle one as perhaps best expressing their view or preference (and to be clear in this Annex the Reserve Bank is not taking a position on the merits of the proposed retrospective amendment).

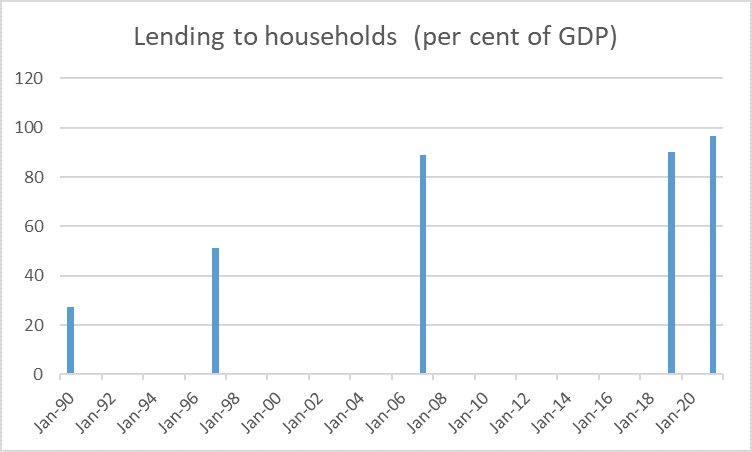

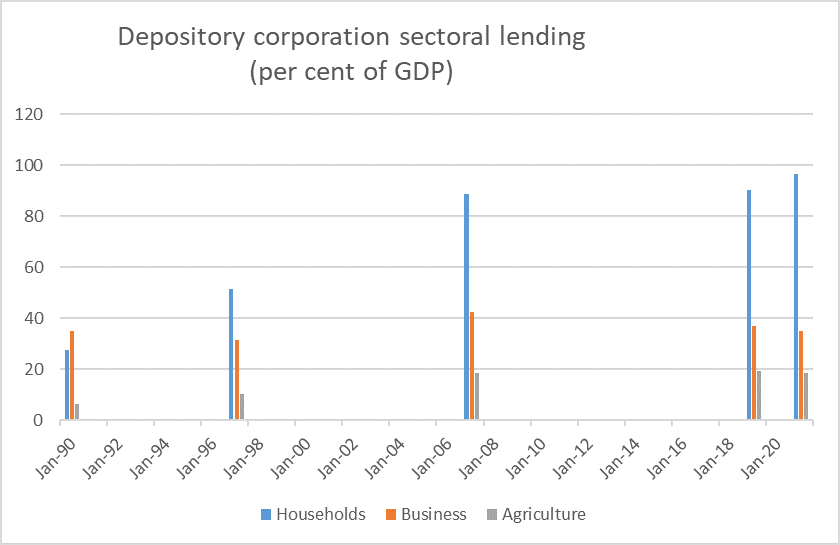

It really isn’t clear how the Reserve Bank came up with the big scary number. Over the period in question – 2015 to 2019 – total housing and consumer loans averaged about $275 billion. If the average interest rate over this period was about 5 per cent, the average disclosure failing occurred half way through the period, and a third of all retail loans in the economy (by value) were subject to disclosure failings, the total interest involved would have been be about $10 billion, which is (I guess) in the same order of magnitude as the Reserve Bank’s $12.9 billion number (especially if one allows for interest on such an amount through to today).

But we know, for multiple reasons, that this cannot be a number to take seriously.

For a start, if the Bankers’ Association and its members thought it was even roughly accurate as an estimate of the sector’s exposure, they’d have hired a consultant economist to churn out quickly a well-explained and documented version of their own (rather than just waving around the worst Reserve Bank numbers, where any details as to how it was done are – perhaps conveniently for them – blacked out). It wouldn’t take long, and the Bankers’ Association clearly isn’t short of money to deal with this issue: at their FEC appearance they brought along three [UPDATE: two apparently] KCs to help testify and answer questions on legal dimensions. One of those KCs – James Every-Palmer – actually told FEC (at about 24 minutes in) that the sums being sought in the cases against the ANZ and ASB were “as I understand it, hundreds of millions of dollars” (before then handwaving to tie this to a system-wide $12.9 billion dollars). ANZ and ASB together make up the best part of half the banking system, so if the Bankers’ Association understands the claims against them to be “hundreds of millions” then even if that represented $1 billion in total, it is all but impossible to see how the rest of the system could be exposed to $12 billion of claims.

There are several reasons for that statement: no other claims have been lodged, the litigation funders told the committee they had heard of no other claims (and any such claims could really only go forward with litigation funding given the cost of civil justice), and the existing legislation is written in such a way that any further claims, not already lodged, would almost certainly be out of time (more than five years on from when breaches were disclosed). I’ll leave those points to the lawyers to argue about, but there is also some hard data on the numbers of customers involved.

The Commerce Commission reached settlements with the four big banks (and Kiwibank) some years ago, and those settlements (which involve compensation for actual loss, and did not preclude civil action by customers) are all sitting on the Commerce Commission website to consult.

Take the ANZ first. This is what had happened.

102000 customers were affected. That appears to have been around 30 per cent of ANZ’s mortgage customers in 2015, and at 31 December 2015 ANZ had about $63 billion of retail credit outstanding.

Under the existing provisions of the CCCFA, customers were not liable for interest in the period between an erroneous notification and either when it was corrected and they were notified, or when they next made a (validly informed) change to their loan. Someone who changed the fixed term of their mortgage in December 2015 (getting incorrect disclosure) is likely to have changed it again before the end of 2019 – say, on average, December 2017 – and received correct information then.

However, as I understand it, the (potential) ability to claim back all interest also only applies to those loans which had been taken out from 2015 onwards, so it is likely to be only a minority who are covered by the current class action suits, given that the poor disclosures only occurred for one year.

It isn’t impossible – depending on the specific assumptions – to get up to a total towards $1 billion of exposure, BUT we already know that is a) more than Bankers’ Association lawyer suggested the claims were, b) more than implied by the plaintiffs’ settlement offer this week (around $300m, suggesting that was around two-thirds of the total exposure).

The ASB situation is a little murkier. For ANZ, the bank knew exactly who’d been affected (and so past actual reimbursements were for actual errors). At the time of its Commerce Commission settlement, ASB did not know how many or who had got the wrong disclosure, only that in total 73000 customers were potentially affected.

The breach went on for longer so a larger proportion of those customers are likely to be able to potentially claim back the interest and fees paid over those years (the median such customer in principle having a claim for about two years of interest). But we have no idea how many customers actually got the correct disclosure – ASB seems not to have had the systems to know, but presumably if this case proceeds will go to lengths (costly lengths) to ensure that the actual victims of procedure “not consistently followed” are identified and only for them might there be an exposure (in the Commerce Commission settlement all 73000 were paid a fixed and modest lump sum, presumably cheaper then than trying then to go through every customer file).

If 20 per cent of the affected (post 2015) customers got the incorrect disclosures, I could produce an estimate as high as $700-800 million. But again, as with ANZ, these numbers seem higher than material in the public domain from those better placed to know already suggests. And even taken together with a high-end estimate for ANZ, nowhere near half of the $12.9 billion for the Reserve Bank’s high-end scary number scenario.

And those are the two banks against whom a case is actually being taken.

Of the other two big banks, BNZ accepted a warning from the Commerce Commission. The number of customers involved was much smaller (11956 in total) of whom 2300 had been directly compensated by BNZ. Meanwhile, the Westpac settlement involved new credit card customers only (so, on average, far smaller loan balances) and only 19000 of them. Kiwibank – while smaller in total – has a substantial retail customer base and seems to have had a similar issue to ASB. It had 35000 new borrowers with a variation potentially affected. But it is hard, even adding all three up, to get to more than another $1 billion maximum exposure. And, to repeat, no class action civil case has been taken against those banks, or indeed any of the smaller lenders, about whom MBIE purported to be so worried. Even if things were not out of time, smaller lenders who’d breached might in any case have been unlikely to have sufficient customers to attract a potential litigation funder).

Only someone with access to really detailed information at an individual bank level could come up with a reasonably robust system-wide estimate of potential exposure in the now, almost impossible event, that cases were to have been taken against any other institutions. But it still looks as though even the Reserve Bank’s second scenario – which they describe as “low impact” on capital ratios – would err on the high side. Based on what the Bankers’ Association lawyers have said, based on what the plaintiff’s lawyers have said, and taking account of the absence of other claims and the likely out-of-time nature of any further claims, it is difficult to see how a worst case involving actual claims before the courts exceeds $1 billion in total.

You can understand why the ANZ and ASB and their shareholders would prefer not to pay such a sum, and would (a) fight it in court, and b), if they could, lobby for a retrospective law change. But it simply isn’t a financial stability issue. It is worth remembering that 15 years ago a big tax case went against the banks, costing them $2.2 billion in an economy then about half the size (nominal GDP) of today’s (and in the midst of a severe recession). Banks affected emerged just fine. When MBIE advised the Minister last October to act to “immediately alleviate distress in the market”, there was (and is) no sign of distress in the market – as it affected ability or willingness to lend, of large players, players being sued, or other lenders – just some “distress” in the local board rooms of ANZ and ASB.

(And note that MBIE’s own advice a month later – page 31 here – was that the proposed amendment was “not clearly necessary to address concerns about the financial position of either ANZ or ASB” and “we acknowledge that applying this amendment to the active class action has “upside” potential for the banks only”.)

Without someone launching an OIA – which the Bank might well stall for several months – we have no way of knowing what the Reserve Bank makes of the use being made by the Bankers’ Association of the $12.9 billion number, or even whether they would still stand by it as a plausible scenario now, 9 months on. But it is pretty clear that – with material then in the public domain – a number on that scale never made any plausible sense, and that the only cases that are actually before the courts – the only cases now likely ever to be – probably involve total stakes less than 10 per cent of that “big scary number”. The banks affected will know that too, but in expected value terms it is no doubt better them to just repeat over and over the “big scary number” and hope to scare the government into passing this retrospective law than to come straight out and acknowledge the plausible maximum scale of any exposure if they lose in courts (and several rounds of appeals) and if the courts made awards fully consistent with the plaintiffs’ claims.

I took from the select committee appearances the other day that while the plaintiffs and their funders oppose the use of retrospectivity on principle, they would (unsurprisingly perhaps) be content with a carveout that meant that the proposed amendment did not apply to cases already before the courts. You can understand why ANZ and ASB would not like that, but why shouldn’t the government and Parliament, particularly once they realise that the big scary number is just a fairy tale, although being used rather more maliciously than a typical parent readings Bears in the Night to their young ones? And yet lawyers for ANZ have the gall to suggest that the plaintiff’s settlement offer this week is “a cynical attempt to influence the law reform process currently before Parliament”. One might well understand why the plaintiffs might make a settlement offer when ANZ and ASB seem to have the government lined up in their corner, but there is no mistaking that brandishing the poor old Reserve Bank’s big scary number is much more evidently an attempt to keep the select committee in line and make public opinion a little less unsympathetic to a law change designed specifically (and only) to help two big (foreign) banks.

For anyone interested, there is a column by Jenny Ruth ($) on related issues this morning.

Finally, regular readers will know that I am not exactly a “bank basher” and have often here derided the rather desperate anti-Australianism implicit in a lot of the NZ political attacks on banks. I think we have a pretty good banking system generally. I’m not necessarily a big fan of the CCCFA in any of its forms (and thought the actual plaintiff who was wheeled up to the select committee the other day was singularly unpersuasive – unlike his lawyer). But I don’t like people playing fast and loose with “big scary numbers”, when they know (or could reasonably be expected to know) that they, and claims made for them, bear little or no relationship to reality. And I don’t like retrospective legislation one little bit.