So, what to make of the Governor’s final decisions on bank capital?

If you are a bank or bank shareholder, you are presumably just grateful for small mercies, the modest extent to which the Governor changed his mind and allowed the banks to use cheaper forms of capital to meet the new requirements. Consistent with that, the share prices of the parent banks recovered some ground yesterday.

Since banks are scared of their regulators and – both here and in Australia – are very reluctant to seek judicial review, despite the very strong sense of pre-determination about this process, and the evident failure to engage seriously with substantive concerns raised by submitters, there isn’t much else they can do. Their behaviour – willingness to provide credit into this economy – can, and probably will, adjust. But if they won’t, or can’t, do anything more about the policy decision, grizzling won’t get them anywhere. Rightly or wrongly, big banks don’t command much public sympathy.

But I’m neither a bank nor a bank shareholder, so I have some different perspectives.

First, a couple of process-y points out of yesterday. We learned from the Governor’s press conference that the banks themselves had been briefed on the announcement early yesterday morning at meetings at the Bank. They had to sign up to a non-disclosure agreement to attend, but once the meeting was over they were allowed to leave and go about their business, hours before the public announcement. Given that the information they’d been given was highly market-sensitive (as we saw in the movement of both bank share prices and of the exchange rate) this was extraordinarily cavalier on the part of the Bank – only 3.5 years on from the last lock-up they ran, where systemic failures on their part allowed a leak from the lock-up itself, in turn leading to a discontinuation of regular lockups.

There was also a lock-up for journalists yesterday morning (who weren’t allowed then to leave before the public announcement, not even if they promised to be on their best behaviour). One journalist told me it was pretty chaotic (adminstratively – access to power etc), but my real concern is what protocols and procedures were in place that would have prevented the sort of leak we saw in 2016 (which involved a journalist in the lock-up emailing the information back to their office). Apparently, there was also a non-disclosure agreement, but how much protection would that have been if someone had attempted a repeat of 2016?

One element of yesterday’s announcement that was new, relative to the consultation document, was a commitment to an annual review of how things are going as the new policy takes effect (progressively over the next seven years). That looks, on paper, quite a reasonable initiative by the Bank, except that……the Bank will be reviewing how a controversial decision they themselves took will be going (more specifically, staff who work to the Governor will report to the Governor their assessment of how the Governor’s own decision is going). It isn’t exactly a recipe for hard-headed or sceptical evaluation. It reminds me of the clause that was in the Reserve Bank Act that required us to report in each Monetary Policy Statement on how monetary policy had been conducted – the original intent clearly being some critical self-scrutiny. The provision fell into disuse, until I persuaded people that we really should follow the law. A box was added to each MPS to deal with the issue. Unsurprisingly perhaps, in the almost 15 years since no fault was ever found with any past monetary policy action or choice. That isn’t really to criticise the individuals involved – except perhaps Governors: the incentives were just set up badly. Wouldn’t it be better to have some independently-appointed party evaluating things, perhaps not every year, but halfway through the seven years and at the conclusion of the process? If, that is, the intent was serious, rather than being mere window-dressing.

But none of those are the big issues that emerge, unaddressed, from yesterday’s decision. The Bank claims to have another document coming, later in the month, that will articulate how they have responded to various points made in submissions, and why. Maybe that will offer some useful insight in time (maybe), but for now we have only what they released yesterday, which included a 20 page document on the decisions themselves and a 111 page regulatory impact assessment and cost-benefit analysis.

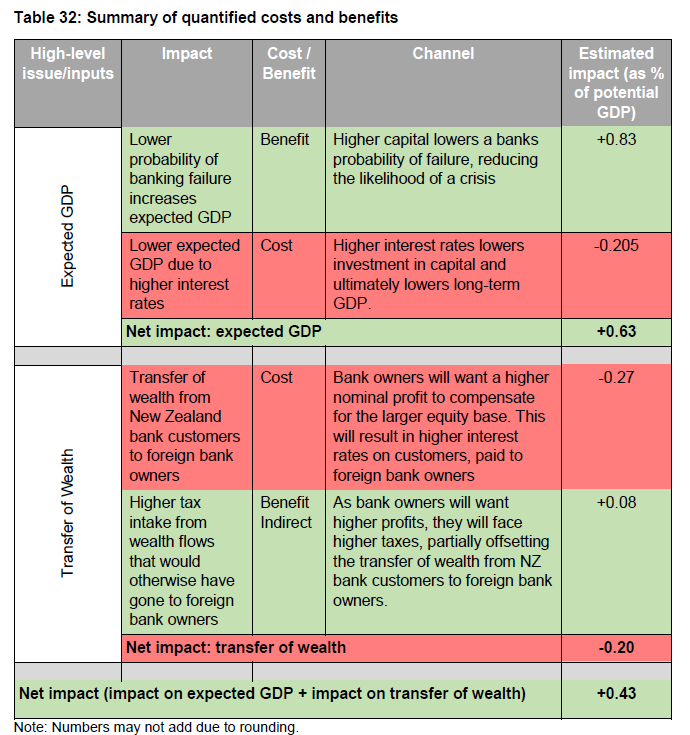

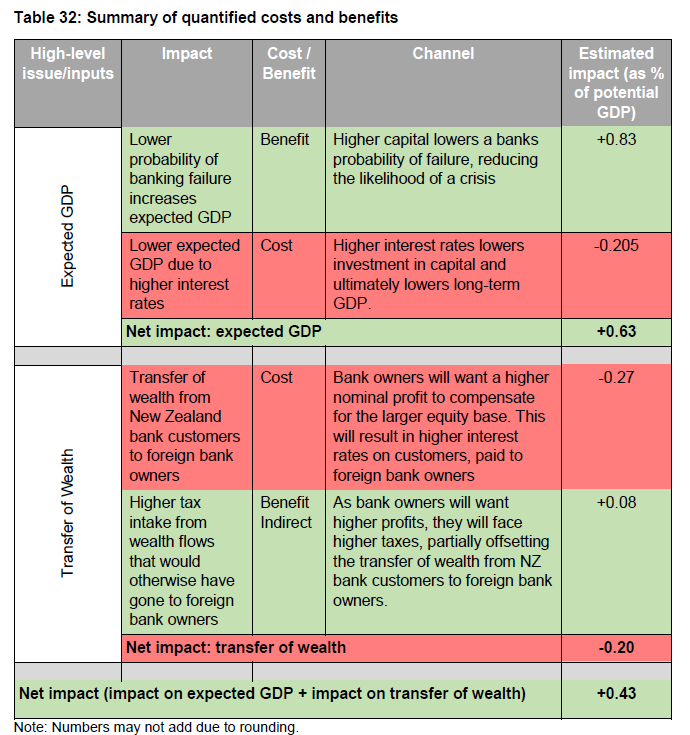

Much of the latter was fairly much a warmed-over rehash of material they had published earlier in the year. Believe their numbers and New Zealanders collectively will be about $1.3 billion each and every year better off a result of (being compelled) to take this insurance policy. That is equal to about 0.4 per cent of GDP, a number which might not sound a lot but (a) is pretty large for an estimate of any microeconomic reform measure, and (b) capitalises up to a very large number (on their preferred discount rate, probably well in excess of $40 billion).

The costs and benefits taken into account in reaching this number include both GDP effects and GNI effects. Specifically, one area the Bank has greatly improved on in the final document is that it now takes explicit account of the fact that higher bank capital ratios will result in materially higher total dollar profits accruing to foreign shareholders in banks. This had been an omission Ian Harrison was particularly forceful on in his submissions and papers on the capital proposal. In other words, some larger proportion of GDP won’t be accruing to New Zealanders, and the cost-benefit analysis rightly focuses on the impact on residents.

Here is the Bank’s helpful summary table.

Red effects are costs, while green effects are benefits. Focus on the costs first.

The first of them is the lower level of GDP (permanently lower) as a result of the higher interest rates estimated to flow from this proposal. The number – minus 0.21 per cent of GDP – is a bit smaller than the Bank estimated in the original documents, consistent with them allowing some of the additional capital to be raised from lower-cost instruments. We don’t know it with certainty, but there hasn’t been that much argument about this number. I’m happy to work with the Bank’s number, while noting that most of the alternative views are of a larger negative effect, not a smaller one.

The second negative effect is the income (rather than wealth) transfer effect to overseas shareholders. Again, there is some uncertainty about the precise magnitude of the number, but I doubt anyone will argue very much with the broad scale of the number. The Bank treats the gross effect and the tax offset as separate items, but on their estimates the after-tax effect is equal to -0.2 per cent of GDP.

Thus, the cost of the insurance policy – on the Bank’s own estimates – is equal in total to -0.41 per cent of GDP. Use their discount rate and plausible assumptions about growth in potential GDP (see my treatment of this earlier), and that is akin to spending a discounted present value $40 billion to buy the insurance the Bank is now compelling us to take. That’s a pretty pricey policy. The precise magnitudes of the costs have margins of uncertainty around them, but we are near-guaranteed to be paying a substantial premium each and every year, as long as this policy is in place (the current Governor, of course, can’t commit beyond his own terms, and there have been numerous changes in the regulatory environment over the decades).

For that (relatively certain) cost, the (expected) benefits had better be good. The Bank reckons (with inevitable margins of error) that they are equal to 0.83 per cent of GDP each and every year. And where do they get that number from? They assume – it is simply an assumption – that by bumping up the capital requirements so much they can – singlehandedly – avert a really serious financial crisis at some point in the future which would have (unaverted) a cumulative output cost of 63 per cent of GDP.

Unfortunately, the Bank shows little sign of having really thought hard about the nature of financial crises or really large nasty economic adjustments. It is all very abstract and ungrounded. Neither in the earlier consultation documents nor in yesterday’s paper was there any sign that the Bank had sought to distinguish the costs that might arise from a crisis itself as distinct from the prior bad borrowing/lending decisions, and resulting misallocation of resources, that may have predisposed a banking system to a crisis. Higher capital ratios may be able to do some good in minimising the former costs, but it is very unlikely they will make any useful difference to the latter ones, especially if one is starting from capital ratios already high by modern historical and international standards. In their defence, they will claim to have taken assumptions from “the literature”, much of which was generated by motivated researchers (often working for central banks) looking to build a case for higher capital ratios. None of the Bank’s work seems to stand back from the numbers and equations to ask what should be elementary questions (even if not always easy to answer). I touched on many of these points in my submission, from which here are some extracts.I made these points in my submission.

Linked to this point, there is very little recognition (none in the main document, and very little in subsequent papers) that many or most of the output losses associated (in time) with financial crises have to do with the misallocation of resources (bad lending, bad borrowing, bad investing) in the preceding boom years. Your documents recognise that one cannot simply measure output losses from a pre-crisis peak (typically a period with a positive output gap) but do not go anywhere near far enough to recognise the significance of this, rather larger, point. In such circumstances, estimates of potential GDP itself may be materially overstated. As far as I can tell, the research papers you quote are open to the same criticism (which is not a defence for the Bank, but – probably – an indication of the predispositions of many of the chosen researchers and their institutional sponsors).

When an economy and financial system has gone through several years of badly misdirected lending, borrowing, and investment, not only is there an inevitability about output losses because of the bad prior choices crystallising, but there is a near-inevitability about both lenders and borrowers being hesitant about doing new business in the wake of the realisation of past mistakes. Prior assumptions and business models prove invalid, and it takes time for risk appetite to revive, and to identify like projects that would prove profitable. That is likely to be so whether or not banks emerge from the crystallisation phase with ample levels of capital. At best, it is only the marginal additional output losses from banks falling into “crisis” (however defined) that is likely to be eased by much higher initial capital ratios – and yet you made no attempt to distinguish this effect.

The Bank also showed no sign of having done any sort of comparative analysis (of that sort done previously on my blog e.g. here https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/07/06/reservebank-dtis-and-the-cost-of-crises/, or here https://croakingcassandra.com/2019/03/04/banking-crises-are-bolts-from-the-blue/ or by PIIE’s William Cline) comparing the output and/or productivity experiences of countries that underwent financial crises with those that did not. This is particularly important in thinking through the experience around 2008/09, when many countries experienced crises and many others did not, all overlaid on what appears to have been a common global productivity growth slowdown. Reasonable people might differ as to how best to do such an adjustment or assessment, but the Bank shows no sign of having even tried. Any plausible assessment of this sort would, however, conclude that plausible additional output losses saved by reducing the probability of any particular loan book incurring losses large enough to run through capital would be much lower than the estimates the Bank uses. Note also that the Cline methodology still overstates the amount that higher capital ratios alone might save, since his output path comparisons include (for the crisis countries) both kinds of losses – from the initial misallocation of resources, and the pure crises effects. Only the latter should be relevant in assessing the costs and benefits of higher minimum capital ratios.

As a simple illustration of some of these points, the US experienced in 2008/09 one of the very worst financial crises in advanced countries for many decades and New Zealand experienced only a very minor financial crisis. And yet the paths of GDP per capita for the two countries were strikingly similar: both were underwhelming, but it isn’t credible to ascribe all the underperformance of the US economy to financial crisis effects, when various other countries had similar experiences (actually US productivity growth (a) slowed prior to the crisis, and (b) post-crisis has been less poor than in many non-crisis countries, including New Zealand).

A much more plausible estimate of the actual GDP savings as a result of averting the true marginal economic costs of a crisis, might be more like 10 per cent of GDP (and even that is large, especially in a floating exchange rate economy). Assume GDP is, say, 1.5 per cent lower than otherwise for seven years – simply as a result of the bank failures, not of the crystallisation of bad decisions pre-crisis – and I reckon you’d have a much sounder basis for evaluating the merits of higher capital ratios. The Bank didn’t even include a number like that in the range of scenarios they looked at (the lower bound they used was 19 per cent, and yet even so in around 15 per cent of their – skewed high – scenarios the benefits weren’t worth the costs we’ll all be paying).

On a similar note – the Bank showing no sign of actually having thought hard about financial crises, nasty economic adjustments etc, as distinct from dropping numbers in a model – is the issue of stress tests. As I and others have pointed out repeatedly, the various stress tests the Bank (and APRA) have run over they years suggest that the banks would come through in pretty good shape even really severe assumed shocks (eg a halving of house prices and a deep and pretty prolonged recession, very large sustained rise in unemployment). That was with the capital levels banks chose to hold, faced with the minimum capital requirements in place for much of this decade. We all know, too, that the banks came through just fine the 2008/09 recession, despite a huge credit boom and substantial asset price inflation in the years prior to that recession. How then can so much higher capital ratios be justified?

As it happens, the Herald yesterday reported that MPs had grilled them on exactly this point as a select committee hearing (on Wednesday) on the latest FSR – good to see some scrutiny. Here is how Hamish Rutherford reported what the Governor said

“While they’re interesting tests, they are not a one in 200 year test,” Orr said of the stress tests, theoretical studies of how banks would cope in times of financial or economic strain. “They’re a one in 50 year test…”

They had a similar line in yesterday’s document

While stress tests are one useful lens on the calibration of capital requirements, there are several reasons why there is no automatic link between the two. First, a given stress scenario will not capture all possible risks facing the banking system, particularly the type of extreme scenario that is being contemplated in the capital ratio calibration of a 1-in-200 year event. The Reserve Bank’s stress tests typically assess a severe but plausible macroeconomic downturn event, the type of which may happen once over a period of several decades. Second, it is difficult to capture the real-world complexities of a financial crisis. Moreover, stress tests only consider the banking system as it is currently. As a result, stress tests did not play a strong role in determining 16 percent as the capital ratio required to deliver a 1-in-200 year risk appetite.

Frankly, it is almost nonsensical – perhaps worse, intentionally – to suggest that the sorts of shocks applied to the Australian and New Zealand banking system in these stress tests are no more than “once in several decade events”. As I’ve pointed out on several occasions – and the Bank has not sought to rebut – there is no example of a modern floating exchange rate economy (and floating matters in the ability to absorb shocks) in which the unemployment has risen by 8 percentage points. There is no example in modern times in which real and nominal house prices have fallen materially more than the sorts of shocks the Bank assumed. And although modern history doesn’t encompass 200 years, it encompasses 40 or 50 years experience for perhaps 30 advanced economies (1200 or more annual – but somewhat correlated of course – observations).

If these aren’t the sort of shocks the Governor has in mind when he thinks of his 1 in 200 year event, perhaps he could tell quite what such an event looks like? So far, through all the consultation documents, there has been no hint of that characterisation. He can’t, surely, have in mind a rerun of the Great Depression – largely a consequence of pre-modern monetary mismanagement, in a climate of fixed exchange rates. If not, then precisely what sort of historical event – or even what sort of stylised event – is he making us pay this huge premium to try to avert?

When he simply refuses to tell us, reasonable people might reasonably fall back on the very stringent stress tests – and all those new supervisors he tells us he plans to hire – to suggest that some of the highest effective capital ratios in the world (right now) are about all the (capital) insurance we probably need. The Governor noted yesterday the banks tend to hold less capital than is socially optimal, which happens because a pattern of government bailouts encourages those who deal with banks to believe they’ll happen again (viz, most recently here AMI). But we’ve had minimum regulatory capital ratios in place for decades now, so simply asserting that – left to themselves – (big) banks might hold less capital than is optimal, tells us nothing about the merits of further increases from the current starting point.

There are plenty of other points I could raise. For example, the Bank depends their discount rate on the grounds it is consistent with the literature, without ever acknowledging that New Zealand interest rates are consistently higher than those in other advanced countries – still true today.

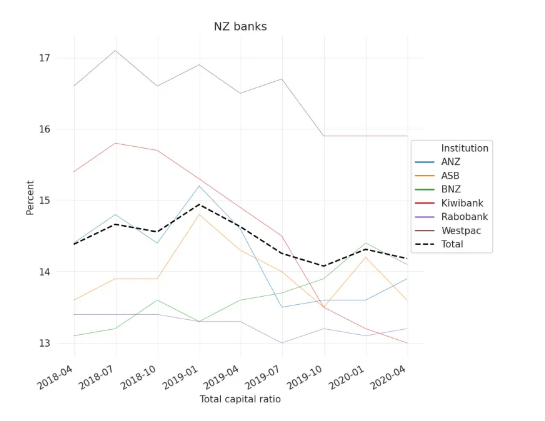

But the final main point I wanted to note was around international comparisons (or, rather, lack of them). Right through the year, from the first release of the consultative document to the documents supporting the final decisions yesterday, the Bank has never attempted to provide a robust comparison of its own capital proposals (now decisions) with the capital requirements in other similar advanced countries. That is particularly extraordinary in the case of the Australia, given that our big banks are all subsidiaries of Australian parents and also affected by APRA’s capital requirements. It should have been a simple and straightforward matter to have

(a) illustrated the headline differences in the minimum ratios APRA proposes and those the Reserve Bank has chosen,

(b) adjusted for the higher floor the Reserve Bank is choosing to apply (risk-weighted assets for IRB banks will have to be no less than about 90 per cent of what the standardised approach would imply, a much higher floor than used elsewhere, and

(c) to have provided a compelling rationale for the resulting (substantial difference).

Here is a quote from an article in this morning’s Australian

The New Zealand reforms require the big four banks to have tier one capital of at least 16 per cent of risk-weighted assets, and total capital of at least 18 per cent. Of the 18 per cent, at least 13.5 per cent will be common equity tier one (CET1) capital of the highest quality, with other tier one capital including redeemable preference shares contributing 2.5 per cent, and tier two capital including long-term subordinated debt accounting for a further 2 per cent. In comparison, Australian rules require banks to have a CET1 capital of 10.5 per cent.

It is a substantially more onerous regime here, with the differences further widened by the differences in the floors in place for IRB bank risk-weighted asset calculations (all else equal, the difference could be as much as another 2.5 percentage points of CET1 capital). These are huge differences, never articulated by the Bank and never persuasively defended – even though, for examples, our banks have large (well-capitalised) parents, and the Australian parents/groups do not.

At FEC the other day, the Deputy Governor attempted to defend the extreme caution

Asked whether the idea of coping with one in 200 year storms was too conservative, deputy governor Geoff Bascand said New Zealand was subject to “an enormous array of shocks”.

“Obviously seismic [shocks], but also as a small, open, trading economy with very high debt levels, we’re exposed to international shocks of potentially great momentum, and so a high level of resilience has some real worth to it.

Bascand has previously tried to claim that New Zealand is materially more risky than Australia – a claim I rebutted here and here. I didn’t see the specific claim repeated in yesterday’s document. Instead, in effect they fall back on bluff and obfuscation, by simply not providing good robust international comparisons, not attempting to justify their stance, and hoping no one much notices.

All this, an enormously expensive additional insurance policy, in a banking system that is already sound and well-capitalised, really does end up looking as though we will pay the (high) price for nothing more than a gubernatorial whim.

(On a final note, for all the talk of seven year transition periods, remember that firms (banks) will adjust their behaviour based on expectations, now knowing the essence of the regulatory environment they will face in New Zealand for the next few (Orr) years. We’d already seen in the Bank’s credit conditions survey that conditions are already tightening, largely due to regulatory factors – points not addressed yesterday or in the FSR. We should continue to expect to see the largest transition – actual scale and distribution uncertain – in the next year or two, not somehow evenly spread over the coming seven years.)