One of the frustrating things about the Reserve Bank’s consultation on its proposal to greatly increase the amount of capital (locally incorporated) banks have to have to conduct their current level of business in New Zealand, is its utter refusal to produce any serious analysis comparing and contrasting their proposals to the rules (actual and prospective) in Australia. The larger New Zealand banks are, after all, quite substantial subsidiaries of the very same Australian banking groups. If there is a case to be made either that the New Zealand proposals are not more materially demanding than those in Australia, or that, if they are, there is a sound economic case for our regulators to take a materially more demanding stance than their Australian counterparts, surely you would expect that a regulator serious about consultation, allegedly open to persuasion (and working for a government that once boasted that it would be the “most open and transparent”) would make such a case. But months have gone on and there has been nothing.

It is striking that over the entire period when the consultation has been open we have not had a Financial Stability Report from the Reserve Bank (I guess it is just the way the timing worked, but still…). With proposals out for consultation that would force banks to have much higher risk-weighted capital ratios, working to the statutory goal focused on the soundness of the financial system, you’d have to assume that any FSR would conclude that the financial system at present was really quite rickety. Perhaps they will when the next FSR comes out late next month, but (a) it would be a very big change of message from past FSRs, and thus (b) I’m not expecting anything of the sort.

A reader pointed out that the Reserve Bank of Australia released its latest Financial Stability Review last week. The RBA isn’t the regulator of the financial system, but works closely with APRA, and has some systemic responsibilities (including the analysis and reporting ones reflected in the FSRs). Capital requirements (on both sides of the Tasman) feature in the chapter on the Australian financial system.

The discussion starts this way (ADI = Australian deposit-taking institution).

You’ll recall that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s proposal would (a) require major banks to have a minimum CET1 ratio of 16 per cent of risk-weighted assets, and (b) would measure risk-weighted assets in a more demanding way than Australia does.

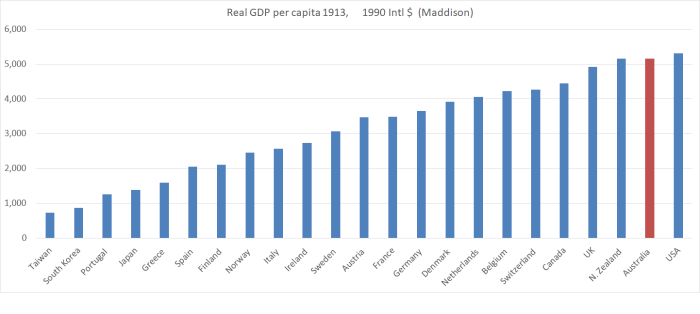

Here is graph 3.6 – a really nice chart with lots of information in a small space.

The first panel is the one of most relevance here, relating as it does to the four banks that have major operations in New Zealand. The regulatory minima are shown in the two shades of purple, and the additional capital held above those regulatory minima is in blue. Three of the four banks are already at the “unquestionably strong” benchmark level.

I also found the the second panel (other listed deposit-taking entities) interesting. In a post earlier in the year, I suggested that too-big-to-fail arguments weren’t a compelling reason for higher minimum regulatory capital requirements, as there wasn’t obvious evidence that entities that no one regarded as too-big-to-fail were required by market pressures to have capital ratios materially above those prevailing at larger institutions. This chart may suggest this point holds in Australia too (deposit insurance muddies the water, but does not apply to wholesale creditors).

The RBA discussion goes on

with a footnote elaborating the point

Unlike the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, they don’t just claim it is hard to do international comparisons, and then blame copyright to defend not presenting any analysis. And APRA has actually published its analysis comparing the way risk weights etc are applied in Australia and other countries.

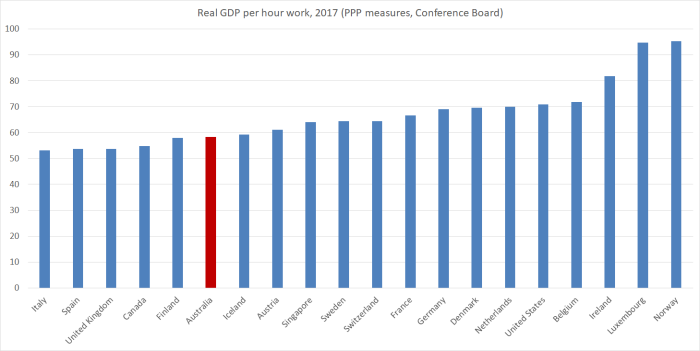

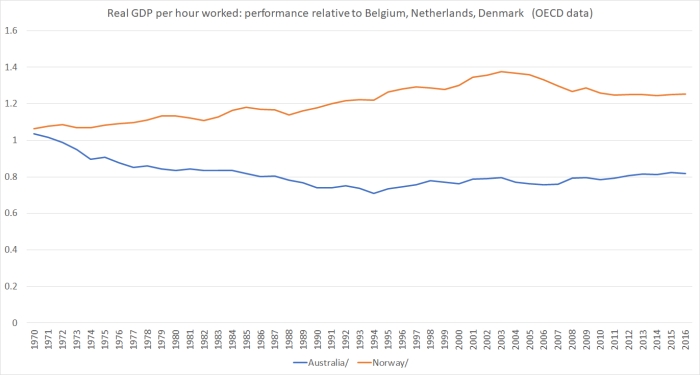

So the Reserve Bank of Australia (and, presumably, APRA) claims that the capital ratios applying to the major Australian banking groups are in the upper quartile internationally, based on actual CET1 ratios of “only” around 10.5 per cent. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand, by contrast, has tried to claim – with no real analysis, just a bit of gubernatorial arm-waving – that its proposed CET1 minima of 16 per cent (measured materially more conservatively again) would also be inside the range of requirements in other advanced countries, probably also in the upper quartile.

At a substantive level, the two claims are just not consistent. Perhaps the Australian authorities are wrong in their claims, but I doubt it. I could advance several reasons to have more confidence in the Australia regulators’ claims:

- they have a much deeper pool of expertise than the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and two agencies (RBA and APRA) able to peer review work in the area before it is published,

- the Australian parent banking groups are all listed companies and there is considerable broker analytical resource devoted to monitoring and making sense of the performance of those banks and the constraints on them,

- for what they are worth, the credit ratings of the Australian banking groups are consistent with them having capital ratios and risk profiles in the upper (safer) part of the distribution of advanced country banks,

- the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has simply avoided the Australian comparisons in all the material it has released (so far).

Whatever the absolute position, we can be totally confident that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s CET1 minima are far more demanding than those APRA applies to the Australian banking groups (16 per cent minimum – perhaps 17-18 per cent actual – vs the benchmark actual of 10.5 per cent in Australia, where the New Zealand requirements will be measured in a more conservative way. Not one shred of argumentation has been advanced by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to explain why they, in their wisdom, think New Zealand banks need so much higher risk-weighted capital ratios. There might be a case to be made – something about risk profiles, or reckless Australian regulators perhaps – but they just haven’t made it (and it would have to be a pretty compelling case given that the major New Zealand banks have large parents – to whom the regulator might expect to look in a crisis – whereas the Australian banking groups don’t). That simply isn’t good enough.

The RBA goes on to discuss the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s proposals.

That text correctly notes not suggest that the headline CET1 ratios required here would be much larger than those applying to the Australian banking groups, but would be measured in a more conservative way than has been the case hitherto (and more conservatively than APRA will be allowing Australian banks to do).

The rest of the paragraph interested me, especially that final sentence. It appears to suggest that the rules would apply differently depending whether the capital of the New Zealand subsidiaries was increased through retained earnings or through a direct subscription of new equity by the parent. In economic substance the two are the same, and regulatory provisions should be drawn in a way that reflects the substance. But the paragraph is perhaps a reminder that one possibility open to the Australian parents, if the Reserve Bank persists with its proposals, is a divestment in full or in part. Comments from the Reserve Bank Governor and Deputy Governor have suggested that they would not be averse to such an outcome, and might even welcome it. I think a much less cavalier approach is warranted and that the New Zealand generally benefits from having banks which are part of much larger groups.

The RBA discussion also has a chart show bank profits in Australia since 2006 (I truncated a bigger chart so the dates aren’t showing).

As they note, return on equity is less than it was in the mid-2000s, not inconsistent with the higher capital ratios (reduced variance of earnings) in place now. The (simple) chart is perhaps consistent with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s story that banks will come to accept lower ROEs on their New Zealand operations over time if higher capital ratios are imposed, but (a) the transition may still be difficult (especially for sectors with few competing lenders), and (b) there is no guarantee, since shareholders will focus on overall group risk/return, not the standalone characteristics of one individual unlisted subsidiary.

Part of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s attempt to obfuscate the Australian comparisons is to muddy the waters by suggesting something along the lines of ‘total capital requirements will end up being much the same, but our banks will have much better quality capital’.

As you can see from their own text, the Australian authorities put much more weight on the core (CET1) ratios, where Australia’s (quite demanding by international standards) expectations will be a lot less than those proposed for New Zealand. But the Reserve Bank of Australia text touches on the additional loss-absorbing capital as well.

Here is the summary of the APRA proposals. These additional requirements, if confirmed, would be able to be met with ‘any form of capital’, including (for example) the contingent-convertible bonds (typically hold by wholesale investors, and which convert to equity in certain pre-specificed distress conditions) which the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has taken such a dim view of (to disallow for capital purposes). This additional loss-absorbing capacity is typically regarded as much cheaper than CET1 capital, and (coming on top of upper quartile CET1 funding) serves just as well in protecting the interests of creditors in the event of a failure of a major financial institution. For any banking regulator interested at all in efficiency that should count strongly in its favour, but even more so in New Zealand where the big banks are subsidiaries of the Australian banking groups, failures will inevitably (and rightly) be handled on a trans-Tasman basis, and where most of what matters is securing a substantial share of residual assets for New Zealand depositors and creditors.

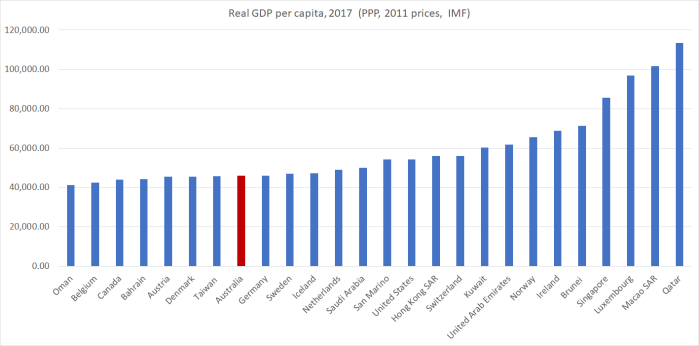

But even allowing for all that, look at the nice summary chart from APRA of their proposals

If fully implemented:

- the APRA proposal for Australian banking groups would amount to a 16 per cent total capital ratio requirement, with risk-weighted assets measured the Australian way, while

- by contrast, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand proposal would involve a 16 per cent CET1 capital ratio minimum requirement (8 per cent in Australia – the CET1 and CCB components), with risk-weighted assets measured the New Zealand way, and

- the Reserve Bank proposal include a plan to raise the minimum risk-weights (in a not unsensible way, considered in isolation) that would mean a 16 per cent CET1 requirement in New Zealand might be equivalent to something like 19 per cent range in Australia. The proposed floor – risk-weighted assets calculated using internal models, relative to the standardised approach – in Australia is, in line with Basle III. 72.5 per cent, and the RBNZ is proposing a 90 per cent floor: apply a ratio of 90/72.5 to give an indication of the scale of the possible effect).

The simple summary is that (even if the Reserve Bank of New Zealand ends up scrapping any Tier 2 capital requirements, and it seems quite ambivalent about them in the consultation document) its capital requirements will be (a) materially higher than those applied to Australia to the parent banking groups, (b) materially more costly, because of a largely-irrational aversion to forms of capital other than CET1, even though we have good reason to take seriously the claims of the Australian authorities (and the sense of the rating agencies) that Australian banks are already among the better-capitalised in the world.

In hundreds of pages of material, slowly released over several months, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has not provided a shred of evidence, or even argumentation, for why locally-incorporated banks operating here should face such an additional regulatory burden, with the attendant economic risks and costs. Add in the refusal of the Bank to provide a decent cost-benefit analysis as part of the consultation (they promise only at the end of it all, when there is no further chance for public input, and no appeals), and there are few grounds to have confidence in what the Governor (prosecutor, judge, and jury – with no appeal court) in his own case is suggesting. We should expect better. The Minister of Finance (and the supine Board) should be demanding more.

For anyone in Wellington next week and interested, Ian Harrison (who used to do a lot of the Reserve Bank modelling work around bank capital) is doing a lunchtime lecture/seminar on the Reserve Bank proposals next Wednesday. You might think I’m fairly critical of the Reserve Bank. Ian is more so, and tells me he has chased every reference in every document the Bank has published in support of its case, and still isn’t remotely persuaded of the merits of the Governor’s claims.