The Treasury yesterday released its latest Long-Term Fiscal Statement. These documents, in some form or other, are now required under the Public Finance Act to be published at least every four years. I was once a fan, but I’ve become progressively more sceptical about their value. There is a requirement to focus at least 40 years ahead, which sounds very prudent and responsible. But, in fact, it doesn’t take much analysis to realise that (a) permanently increasing the share of government expenditure without increasing commensurately government revenue will, over time, run government finances into trouble, and (b) that offering a flat universal pension payment to an ever-increasing share of the population is a good example of a policy that increases the share of government expenditure in GDP. We all know that. Even politicians know that. And although Treasury often produces an interesting range of background analysis, there really isn’t much more to it than that. Changes in productivity growth rate assumptions don’t matter much (long-term fiscally) and nor do changes in immigration assumptions. What matters is permanent (well, long-term) spending and revenue choices. And from a purely technocratic perspective – and Treasury are supposed to be technocrats, not politicians – the headline out of yesterday’s release should probably really be “there is no great urgency about doing anything much over the next 20 years”. In this chart, from the report, in 2035 spending as a share of GDP, on historical patterns and existing laws, is only around where it was in 2010.

John Key – the Prime Minister who refuses to do anything about NZS – almost certainly won’t be in office that long.

There were several interesting background papers Treasury released yesterday. If I get time over the next few weeks, I might write about some of them here. For now though, I simply wanted to highlight some interesting material in the main report on a couple of my favourite topics: Auckland’s economic (under)performance, and immigration policy. I’m not entirely sure why either section was included in the report – which is about fiscal projections – but there they are.

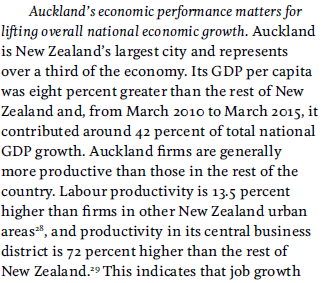

First, Auckland. Here there are some encouraging signs that Treasury is finally recognising the problem. A few months ago I was quite critical of a cheerleading speech about Auckland given by the Secretary to the Treasury. And in the LTFS, the text starts off quite upbeat

I was drumming my fingers at this point, but then I got to the second half of the paragraph.

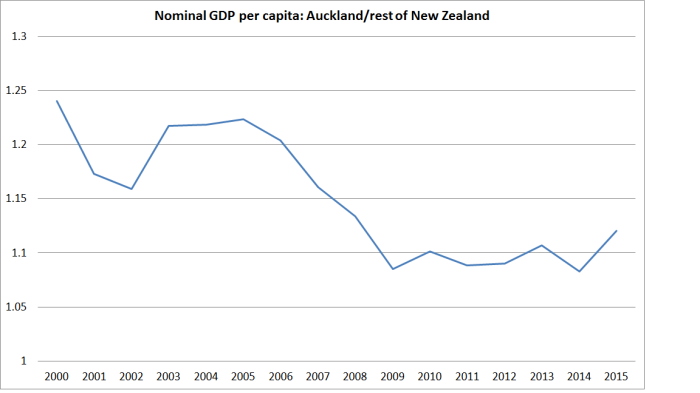

There was much more that could have been said, but for Treasury to acknowledge quite openly – the plain statistical fact – that Auckland incomes have been falling relative to those in the rest of the country, despite the huge infusion of additional people (“most skilled migrants anywhere in the OECD” as I heard Steven Joyce say again this morning) should be seen as pretty damning. There is something very wrong with the model: as they add “this suggests we are not seeing the agglomeration effects we would expect from Auckland’s size and scale”. Perhaps there is no guarantee – or even reason to think – that putting an extra million people or so (the increase in Auckland’s population in the last 50 years or so) in a remote corner of the South Pacific would generate particularly favourable productivity results.

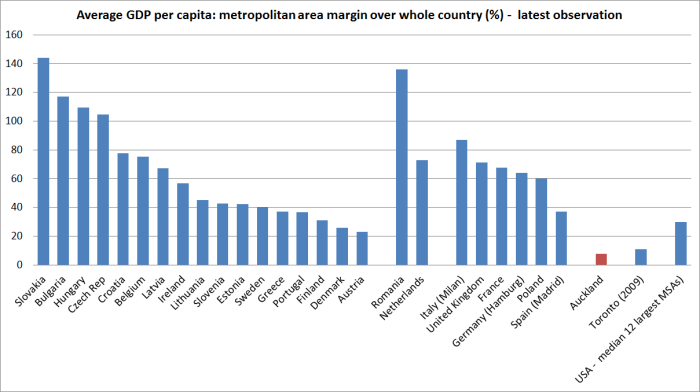

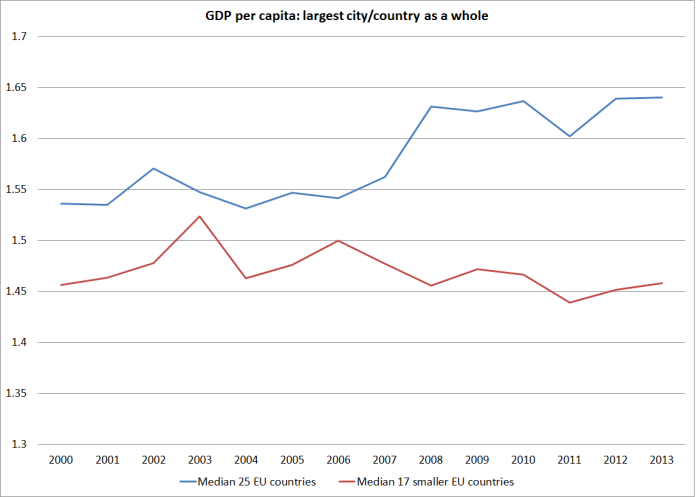

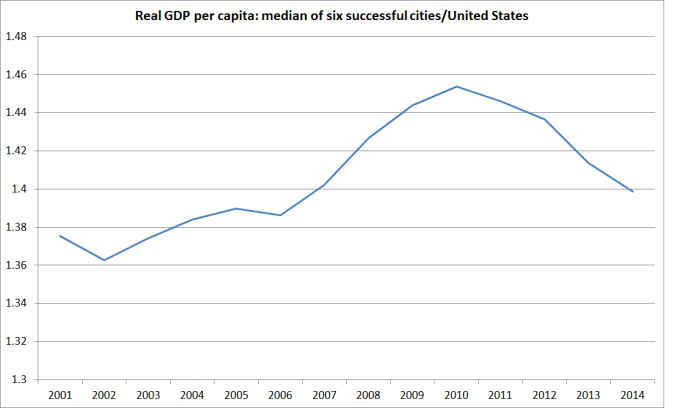

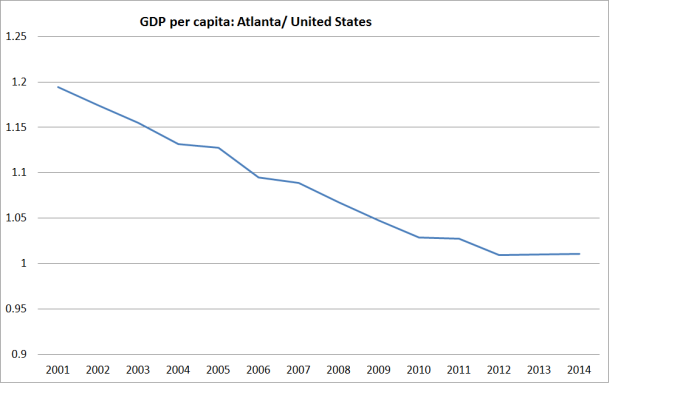

As I’ve noted previously, not only is Auckland’s GDP per capita less high relative to the rest of the country than it was even 15 years ago – the point Treasury now acknowledges – but that margin is small compared to what we see in other countries. I ran this chart, looking at other large cities, in a post a few months ago.

Auckland does poorly. To me, that isn’t surprising. This is a strongly natural resource based economy. There is no sign – and no sign Treasury points to – that it has needed lots more people, and especially not in Auckland.

But Treasury, while clearly a bit troubled, isn’t willing to abandon the faith just yet. The section on Auckland goes on. There are a couple of anodyne paragraphs on Auckland as gateway (people and goods), and Auckland’s transport system, and then we are right back to credal statements.

Perhaps diversity does bring advantages, but in the specific case of Auckland, there is just no evidence of solid economic gains. As Treasury notes, Auckland has a fast-growing population, a young population, a culturally diverse popuation, and a very high proportion of people born overseas. But it has a disappointingly poor- and worsening – relative economic performance. In my hard copy of the report I had scrawled next to the comment about London “just a shame, we don’t have their GDP performance”. In the chart above, you can see the contrast between London and Auckland. We really should expect more than faith-based claims from the government’s premier economic advisory agency. As Treasury knows, for example, there is no evidence of a causal relationship between immigtration to New Zealand and growth in innovation, productivity or exports.

(For those interested in the Auckland underperformance issues, the October issue of North and South magazine had a nice article on The Delusions of Aucklanders (and perhaps those advising governments). The article is now available on the new Bauer Media website, Noted.)

Some pages on from the Auckland discussion, Treasury has a page on immigration. It also starts off with a strongly credal tone – keep the faith.

After finishing guffawing at the rather desperate “Auckland as a city of global significance” – had the 9th floor of the Beehive requested that touch, or did they not need to ask? – we might simply ask for some evidence. You might think it would trouble Treasury, even a little, that with one of the largest immigration programmes in the world – of people who, by world standards, are not that badly skilled – we’ve had 25 years of one of the lowest rates of productivity growth in the world. Even Treasury acknowledges that failure. Perhaps there isn’t a causal relationship. Perhaps the productivity performance would have been even worse without the immigration. But not a hint of doubt is allowed into this discussion from our premier economic agency.

But then the drafting gets a little more cagey.

Note very carefully the “can”. Yes, in principle, a good immigration policy can support productivity etc in the right places/circumstances. But Treasury can, and does, advance no evidence that it has, in fact, done so in New Zealand. They really want the public to believe in the programme, while being skilful enough drafters not to allow themselves to be pinned down to have made claims that the economic performance of New Zealanders is actually better as a result of the large scale immigration programme. There is no hint of any evidence that using immigration policy in “addressing short-term skill shortages” makes any difference to longer-term per capita growth and productivity (and I’ve seen no literature on that point internationallly either). And actually, Treasury’s own scenarios suggest that immigration also makes very little difference to the longer-term fiscal challenges.

They conclude, perhaps a little uneasily, reverting to rather more jargon-ridden text.

Be very wary of bureaucrats proposing “integrated system responses”, when markets have ways of dealing with issues. Typically, when demand for additional labour and human capital is high, returns to that sort of labour rise, which attracts more people into those jobs, and to developing those skills. “Skill shortages” – or even “workforce planning” – just aren’t some sort of a chronic problem governments need to address. Excess demand for labour is either a sign that monetary policy is a bit loose, or that wages (for that sector or industry, or across the board) should be rising. And if Treasury – or MBIE or ministers – could produce strong evidence that our immigration policy really had boosted productivity and the material living standards of New Zealanders, that would be one thing. But they can’t – and don’t. And don’t forget, that the same OECD survey Steven Joyce was citing again this morning shows that native New Zealanders already have some of the very highest skill levels in any OECD country.

Overall, I guess one gets a sense that Treasury is slowly losing confidence in bits of its story. They now are prepared to acknowledge (at least part of) the sustained underperformance of Auckland. They have raised some doubts about excess reliance of some industries on immigrants. And they still can’t cite any real evidence of sustained gains in the living standards of New Zealanders from the large scale non-citizen immigration programme. But rather than openly addressing the genuine uncertainty – and in what seems a slightly desperate attempt to keep spirits up, and encourage people to “keep with the programme” – we are left with what are little more than slogans, simply asserting the alleged economic gains to New Zealanders from diversity and high rates of non-citizen immigration. A reasonable response should be “well, show us the evidence”.

At the session Treasury hosted yesterday for the release of the LTFS, we were informed that the Productivity Commission is releasing next Monday its “narrative”, in which they will attempt to explain why the New Zealand economy has underperformed for so long, and (presumably) some thoughts on how best to reverse that. I will look forward to that document – there aren’t enough developed competing narratives around a really important issue – and I will no doubt be writing about it here. Given the Productivity Commission’s statist tendencies, I’m not optimistic, but I will be particularly interested in how they deal with the immigration policy and Auckland issues, both in explaining the underperformance of the last few decades, and in contemplating a better way ahead.

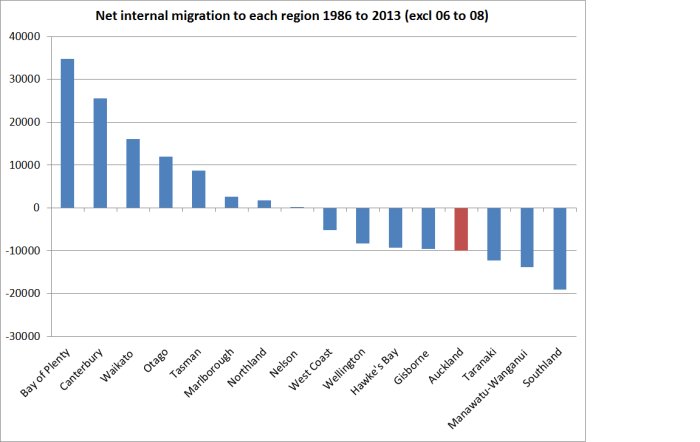

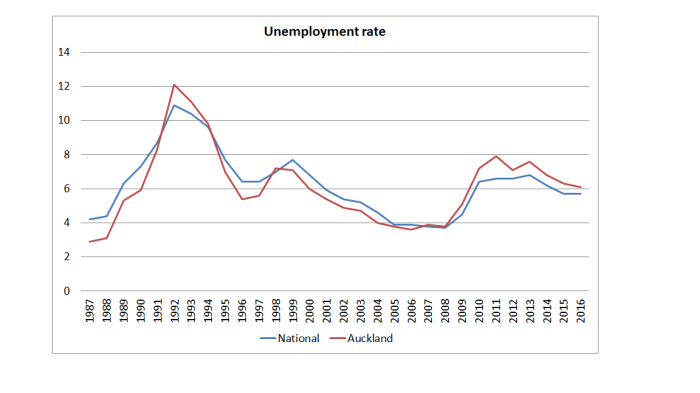

And it isn’t just that Christchurch has had a very low unemployment rate through the repair and rebuild period. Graphing the Auckland unemployment rate against that of the median region produces much the same picture.

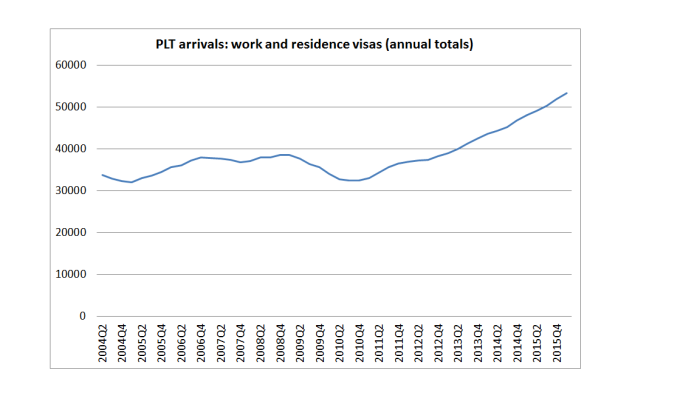

And it isn’t just that Christchurch has had a very low unemployment rate through the repair and rebuild period. Graphing the Auckland unemployment rate against that of the median region produces much the same picture. And the massive increase in student visa numbers (mostly to second tier non-university entities), many of whom later acquire residence, is on top of that.

And the massive increase in student visa numbers (mostly to second tier non-university entities), many of whom later acquire residence, is on top of that. Net, a small number of New Zealanders left Auckland for other parts of the country. Relative to Auckland’s population, the estimated outflow is tiny, but there is just no sign of New Zealanders flocking to the “success” of Auckland (and note that this period includes the outflow of people from Christchurch in couple of years after the earthquakes). Perhaps things have been different in the last three years, for which we don’t yet have data.

Net, a small number of New Zealanders left Auckland for other parts of the country. Relative to Auckland’s population, the estimated outflow is tiny, but there is just no sign of New Zealanders flocking to the “success” of Auckland (and note that this period includes the outflow of people from Christchurch in couple of years after the earthquakes). Perhaps things have been different in the last three years, for which we don’t yet have data.