There is an op-ed on the Herald website this morning on “The role of corporate profits in inflation”. It is written by Max Harris, a lawyer and political activist. He was campaign manager for Efeso Collins in the Auckland mayoral race last year, which should give you a sense of how far to the left he sits on the political spectrum.

Harris is a smart guy, and it is evident from the article and his tweets that he has read a number of papers that have emerged recently from overseas academics and some central bankers suggesting that corporate profits might have some distinctive role in explaining the recent surge in inflation. I say “distinctive” because in the same way that nominal GDP can be decomposed into price and volumes, it can also be decomposed into returns to labour and returns to capital. In a demand-driven surge in inflation it would entirely normal to see all four of those items growing at above-average rates. And since both wage rates and employment tend to be stickier (slower to adjust) than profits – which are the residual, what is left over after other business expenses have been met – it shouldn’t be unexpected to see profits rising and falling earlier and more markedly than, say, wages. That wouldn’t tell you that profits were “to blame” for the inflation in any meaningful sense.

I’m not going to devote this post to unpicking the entire literature on profits and this cycle. Instead, I just wanted to present a few New Zealand charts.

One of the few things I agree with Harris (in this article) on is that New Zealand economic data is not really fit for purpose. There are significant gaps, in coverage, frequency, and timeliness, which really should be remedied. There aren’t (m)any votes in good economic data but it is the sort of thing good governments should be spending on nonetheless.

All that granted, it was striking that there was only one New Zealand specific number in Harris’s article

Now, to be fair, op-eds don’t provide for a limitless word count. But it isn’t hard to do much better than that one number.

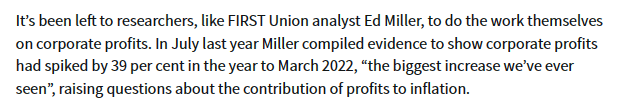

I found a description here as to what Ed Miller had done (note that his calculation was done nine months ago) and replicated his number. Using the Treasury monthly tax database, sure enough you find that company tax revenue (whether including or excluding refunds) for the year to March 2022 was 39 per cent higher than it had been in the year to March 2021.

But here is some context

For the 12 months to February 2023 net company tax revenue was up 7.5 per cent on the 12 months to February 2022. The most recent nominal GDP data is only up to December 2022, but nominal GDP in the 12 months to December 2022 was 8.5 per cent higher than in the 12 months to December 2021.

But perhaps the key point is that company tax revenue is very volatile (in the 12 months to April 2017 the annual growth had briefly reached 50 per cent), with deep troughs and high peaks. That isn’t just because profits can be volatile, but also because of loss carry-forward provisions (when your firm makes a loss one year IRD won’t send you a cheque, but you can credit those losses against future profits (if/when your firm returns to profit). When those losses are exhausted, revenues can jump up very quickly even if profits themselves are less variable.

In this specific case, of course, the year to March 2022 (which Harris cites) followed the year to March 2021, a year in which net company tax receipts had been down 17 per cent.

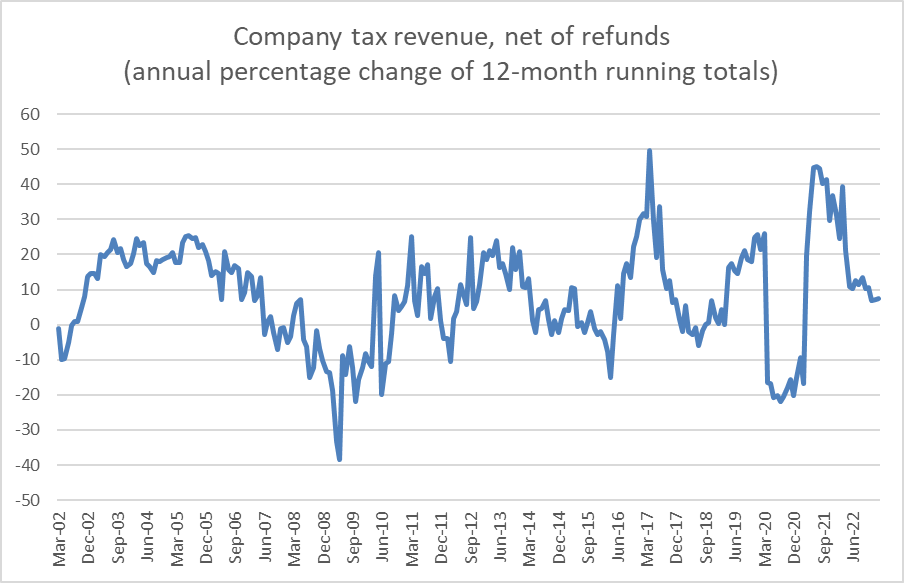

We could dig a little deeper on the same Treasury spreadsheet. Treasury breaks out income receipts from NZSF and GSF, which are really just branches of the central government itself.

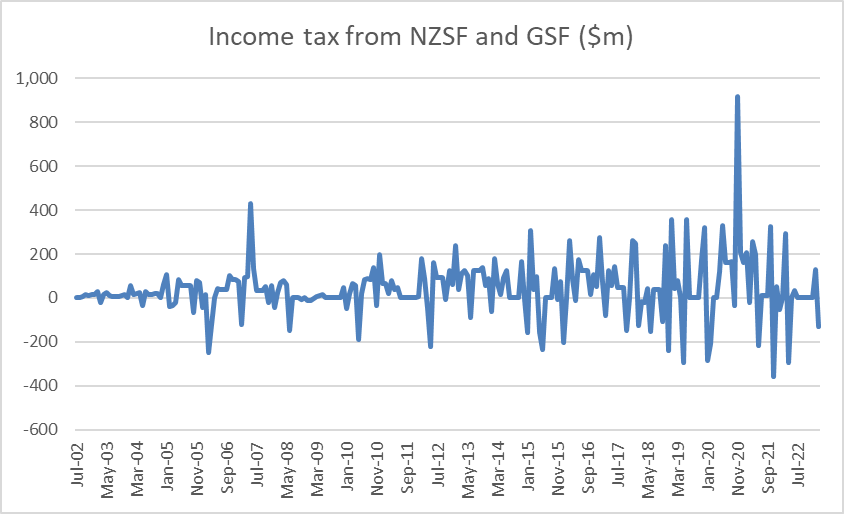

NZSF (the big dollars here) was only set up 20 years ago, so the initial figures were mostly small. These days it is large and has quite volatile returns (and, it appears, tax liabilities). Here is what the corporate tax line looks like with NZSF and GSF income tax removed (which is one of the adjustments Treasury does to get to core Crown measures of tax)

The recent peaks and troughs are even larger. (Note that when, as they did in the 12 months to March 2021, tax revenue from this source falls 30 per cent it then needs to rise by about 42 per cent just to get back to the starting level ($m).

Strangely, we rarely hear much from people like the Green Party when company tax revenue is falling sharply.

One of the gaps in New Zealand’s macroeconomic data is a full quarterly income measure of GDP. However, SNZ has made steps in that direction in recent years, and we now have a quarterly nominal income measure of GDP and a compensation of employees component of quarterly nominal GDP.

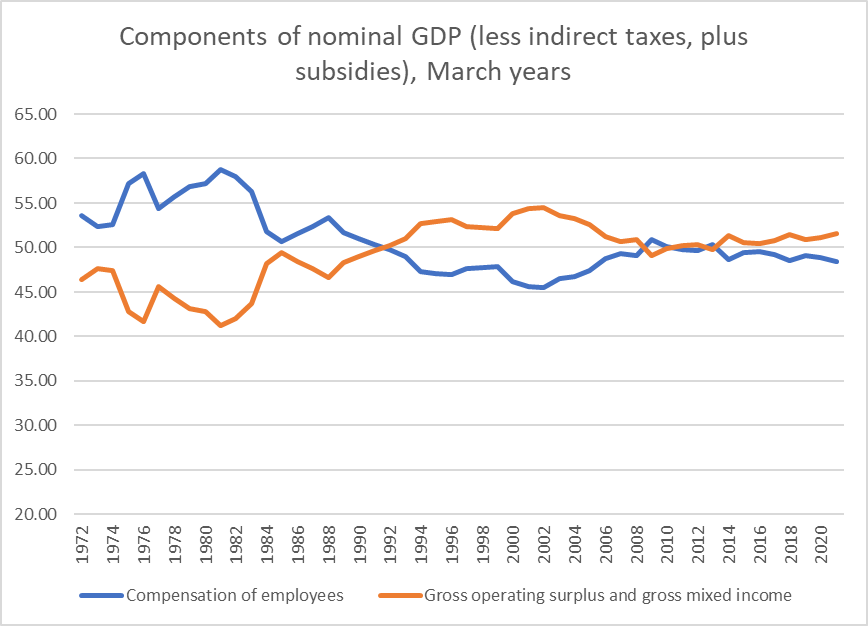

As context, here is the annual data showing both compensation of employees and operating surplus/mixed income up to the year to March 2021

The labour share of GDP (at least the bit going to employees) has fallen a bit in the last decade, but then it has risen a bit more in the previous decade (profits and mixed income share vice versa).

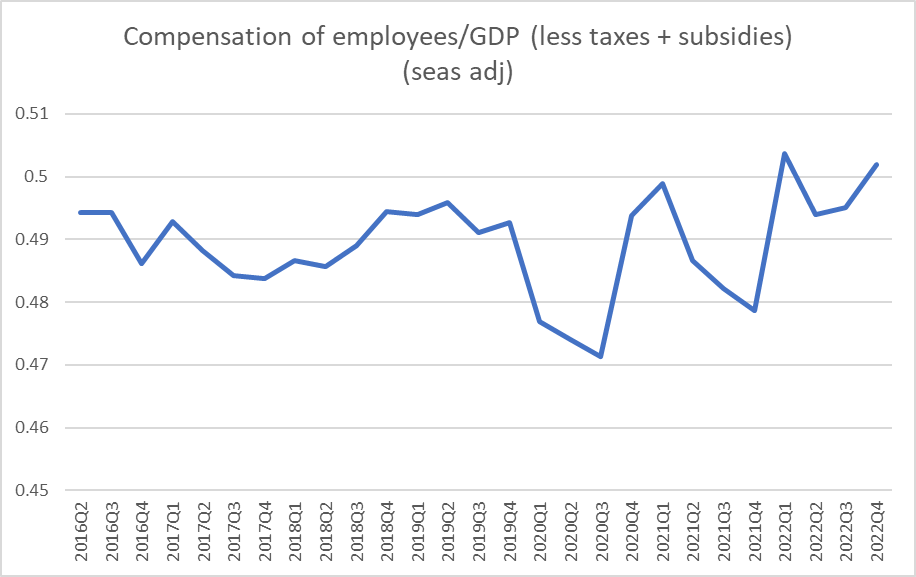

The quarterly data only start in 2016 but are right up to date (December 2022 quarter)

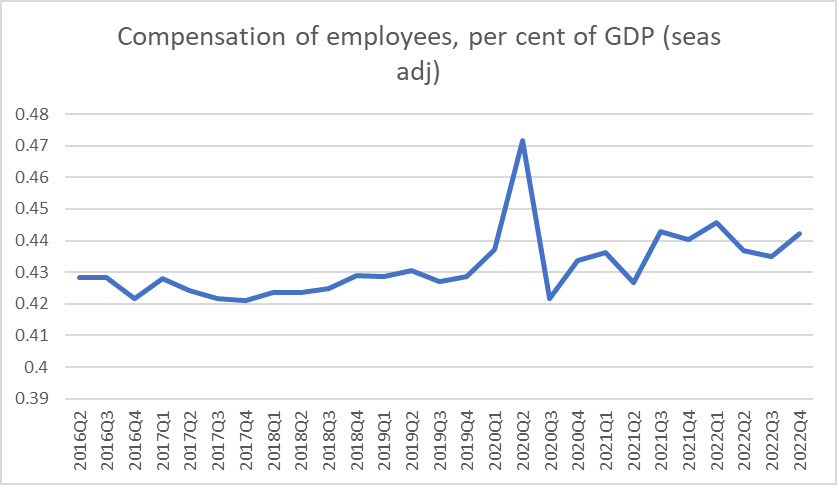

The Covid wage subsidies muddy the picture (sharp shortlived dips in both 2020 and 2021) but over 2022 as a whole the compensation of employees share of (adjusted) nominal GDP was higher than it had been pre-Covid. The picture may be clearer simply as a share of nominal GDP

That isn’t particularly surprising. It isn’t that wage rate growth has run ahead of general inflation or nominal GDP growth, but that the number of people employed, the number of jobs, has increased very rapidly, and the labour market has been running very tight (really on whatever measure you choose to look at). As a reminder if the wage share of nominal GDP has risen a bit amid the inflation surge, that means the other components of GDP (profits and mixed income) have…..shrunk a bit as a share of nominal GDP.

None of this to suggest that pro-competition reforms would not be welcome in New Zealand. They would (although in many cases we could expect the Green Party to oppose them), but the presence or absence of such restrictions is unlikely to materially explain developments in inflation of the scale we – and many other countries, many with more liberal competitive markets – have experienced in the last couple of years. Prima facie, responsibility still looks to rest – as it usually does when such things happen – with monetary policy, either having actively poured fuel on the fire, or (more usually) not having recognised and responded to emerging demand-led inflation anywhere early or aggressively enough.

Readers might also find useful a new column on The Conversation by a professor of economics at Waikato. He puts more weight on that brief Treasury analysis than I did (see previous post), but ends up in a very similar place.

Occam’s razor isn’t always the most useful approach, but when one has had highly expansionary monetary and fiscal policy and have had unprecedentedly low unemployment rates (and general difficulties finding staff), the onus would appear to be on those who want to explain anything very much of New Zealand’s core inflation (in particular) by factors other than the conventional macroeconomic ones. Harris’s column doesn’t credibly make such a case, or point to other New Zealand specific work that does. But, yes, in demand-led booms (especially the early stages) profits will tend to be strong. That doesn’t shift the responsibility off central banks, any more than would be the case when there is a surge of wage inflation, again reflecting unsustainable excess demand for labour.

UPDATE:

To be clear, I am not (repeat, not) suggesting that all of the rise in company tax revenues in the year to March 2022, as cited by Miller, was simply a reversal of the fall in the previous year. About half of it was (company tax revenue was down 17% in the previous 12 month period). My wider point that is an unexpected surge in demand – and it was totally unexpected by macro forecasters – will show up first in profit growth.

As a grossly oversimplified illustration: the local fish and chip shop might have half a dozen staff rostered on on a Friday night. If a lot more people turn up than usual for a Friday night, (not only will wait times be longer but) profits for the day will rise a lot. Wage costs won’t have changed – rosters and wage rates were set in advance – rent won’t change, lighting costs won’t change, but there will be an increase in the cost of goods sold (materials – fish, chips, perhaps oil). If demand remains stronger for longer, you might expect more people to be rostered on, perhaps their wage rates to rise, and so on. Revealed preference suggests workers generally prefer to shift short-term risks – upside and downside – onto firms, and profits will fluctuate accordingly.

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

I doubt there is much long term correlation anywhere between corporate profitability and inflation ( excepting those places where there is strong monopolistic conditions), pretty sure there isn’t in the US.

One flaw is if those corporate profits numbers are measured after depreciation ( which they probably are) then wouldn’t one need to consider net domestic product to be consistent ?

LikeLike

On your final point, yes fair point altho depreciation is a very stable item so using NDP rather than GDP as denominator wouldn’t change any cyclical patterns

LikeLike

I put Max Harris’s article aside for later and never returned to it. Judging from the title something that is bad ‘Inflation’ was the responsibility of ‘Profits’ with the logical deduction that therefore profits should be discouraged. Corporations are owed by shareholders who are individuals and pension funds and insurance companies. I’m not too troubled by who takes the profits so long as our NZ IRD gets its share. Individuals are not my concern but the economic success of pension and insurance firms certainly are.

Some of your article was more technical than my mind could handle but the fish shop analogy helped.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Source link […]

LikeLike