That heading probably describes a great deal of what goes on in the numerous public policy agencies in the central Wellington (well, no doubt local authorities as well) but this post is about the Reserve Bank’s latest.

Last week they released a paper headed “An overview of the distributional effects of monetary policy”. It was under the name of one their young analysts, and carries a standard disclaimer that “views expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Reserve Bank”, but we can safely discount that. No paper on a topic this potentially contentious is going to have got out the door without the explicit imprimatur of (a) the author’s manager, (b) the Reserve Bank’s Chief Economist (that voiceless government-appointed member of the MPC, from whom we’ve had not a single speech in his entire time in office), and most probably the clearance and comfort of the Governor and the Assistant Governor responsible for monetary policy. If the (apparently largely toothless) external members of the MPC didn’t get to sign it off, equally it isn’t likely that it would have been published if they’d had any major concerns. All in all, it is only reasonable to take this document as the official view of the Bank’s hierarchy, reflecting that same hierarchy’s view of acceptable standards of analysis and argument.

It is a strange and inadequate document in a variety of ways. First, and perhaps least important, is the spin. In the previous paragraph I gave you the official, and rather neutrally expressed, title of the Analytical Not. But if you were signed up to the Bank’s email notification service you got this at the head of the email from one of their myriad comms staff.

Immediately followed by this sentence, which doesn’t appear in the Analytical Note itself, and is clearly the responsibility of the more politicised part of the Bank.

There are winners and losers when interest rates are cut, but the international evidence is not clear that this always means the rich get richer and the poor are worse off.

Note that “always”. Whoever wrote this seemed to have in their mind – or to want to feed into readers’ minds – a sense that “when interest rates are cut” it is mostly – just not “always” – a bad thing in which, typically, “the rich” get richer and “the poor” get poorer. It is about the standard one expects from a Year 10 Social Studies teacher, not from those actually charged with the conduct of the country’s monetary policy.

I didn’t want to skip over the spin, because it tells you about the standards of those at the top of the organisation. But in the end it is spin, and on this narrow point the Analytical Note itself is less bad. It is doesn’t contain those block-quoted words at all, and in fact the very first sentences of the paper, highlighted as Key Findings are

Monetary policy easing and tightening can potentially affect the distribution of wealth and income through

several channels. The overall effect of monetary policy on inequality is indeterminate and depends on the

strength of each channel, which may reinforce or offset each other.

Much less inflammatory. It is followed by the second Key Finding

International empirical evidence on the distributional effects of monetary policy is inconclusive. It is not clear

that monetary policy easing, be it through reductions in policy interest rates or by central bank asset

purchases, necessarily reduces or worsens wealth inequality and income inequality.

In other words, not the slightest suggestion that mostly – if not “always” – interest rate cuts make the rich richer and poor poorer.

I haven’t read all, or probably even most, of the international empirical studies they summarise here

and there is not even a hint of any Reserve Bank of New Zealand empirical research in the Analytical Note, so my comments in the rest of the post are really about how the Bank discusses the issues, and the evidence that reveals for how carefully and comprehensively they think through things. It isn’t a long paper – about five pages of text – but that is their choice: unlike say the Monetary Policy Statement (where we might expect this to be touched on next week) there was no practical limit to them taking just as much space as they thought was needed to give a careful treatment of the issue.

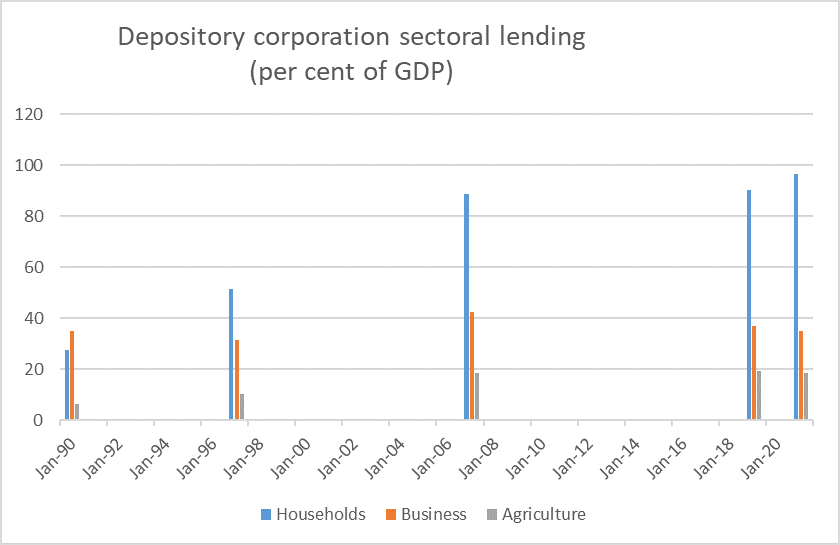

There are plenty of individually reasonable sentences in the paper, and a variety of charts (several designed to show that distributions of income/wealth in New Zealand are similar to some of the other countries that formal studies have been done for). The problem is the lack of a disciplined framework.

For example, it isn’t even clear whether what they are focused on is monetary policy actions – which they (and their models) usually conceptualise as discretionary actions taking as given developments in the (changing and not directly observable) neutral or natural rate of interest – or all changes in interest rates. There is a huge difference in the two.

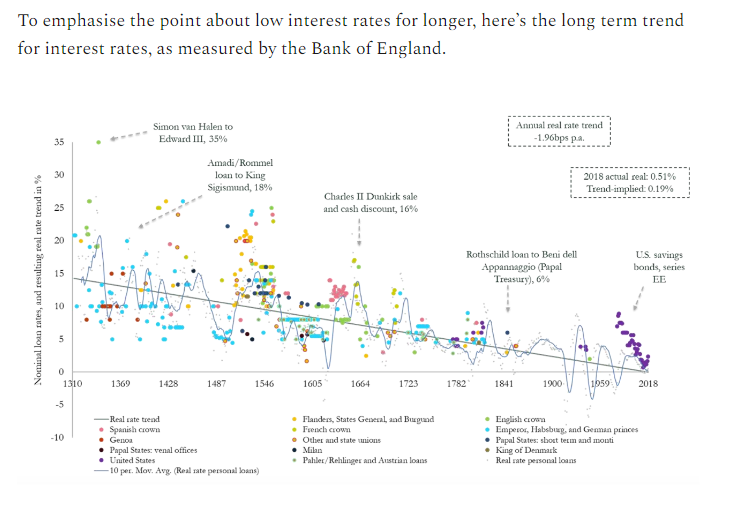

Twenty five years ago, very long-term real interest rates in New Zealand (eg), proxied by indexed bond yields, were touching 6 per cent, and now they are just under 1 per cent (about the same as they were just prior to Covid). Understanding why real interest rates have fallen that far – and similar trends are evident in other countries – or even why our real interest rates are still quite a bit higher than in most advanced countries – is a challenging and contested issue. Understanding the full implications isn’t that easy either. But few seriously suppose that the cause is monetary policy – and the Reserve Bank (in all its past published material) has never been among those few. One can debate the relative contributions of demographics, productivity growth slowdowns, or whatever – again, both causes and implications – but they aren’t things that have anything more than the most peripheral connection to monetary policy as typically conceived (as conceived by Parliament in setting out the Bank’s powers and mandate).

Now, there can be some confusion in the general public mind because if the longer-term neutral real interest rate falls from 6 per cent to 1 per cent then – given that the Reserve Bank chooses to peg the OCR (it needn’t, but it generally a sensible and practical way to conduct policy – over time the Bank will need to cut the OCR by more or less the same amount. Those adjustments are announced as part of Monetary Policy Statements and OCR reviews undertaken by the Monetary Policy Committee. But if you are wanting to think and talk about the impact of monetary policy choices – and much of this discussion, at least in a New Zealand context, has been sparked by events of the last year – you want to talk about discretionary monetary policy actions: things the Bank thinks it is doing to push actual interest rates below (or above for that matter) what it thinks of at the time as the neutral rate. Anything else just conflates two quite different things. And since long-term interest rates will move about whether or not we have an active central bank, while discretionary monetary policy is a choice, if we are thinking about what value discretionary monetary policy adds we – and the Bank – should focus on the implications (all of them) of those discretionary choices.

So one of the other things that is almost entirely missing from the Analytical Note is any sense that discretionary monetary policy actions are temporary in nature. Monetary policy is about keeping unemployment as low as possible consistent with inflation staying in check (that isn’t quite the way the law is written but it is what it amounts to, and is a better framing). Most of the shocks that monetary policy responds to – although this distinction isn’t made in the paper either – are what are thought of as “demand shocks”: some events, perhaps a slump in overseas economic activity, weakens demand, activity and employment here, tending to push unemployment up and inflation down. Monetary policy is about leaning against those pressures with the aim of getting back to a full employment/inflation at target outcome faster than otherwise. But these are temporary events. As the unemployment rate gets back to sustainable/full levels, you want interest rates to be back around neutral. The temporary nature of monetary policy actions is consistent (a) with a standard view of the long-run neutrality of money (in the long run, monetary policy can affect inflation, but not materially anything else), and (b) the experience in past decades, when short-term rates went and down, through quite large cycles. The Bank’s note acknowledges this point in passing in discussing the overseas papers but not in discussing New Zealand.

There is also no discussion in the Analytical Note of the difference other regulatory regimes may make. Thus, if you are bothered by house prices developments – as you probably should be – you might want to recognise that house prices behave differently when governments intervene to restrict land use and make new building harder and slower than in markets where new land and housing supply is more responsive. But even here there is an important distinction that the Bank’s paper just does not make: even if you believe that monetary policy developments in the last year have contributed materially to the recent further rise in house prices, unless you think that Covid has driven the neutral interest rate materially lower, those effects should be short-term in nature. If you are one of those who, for example, think that within the next 12-18 months the OCR will be back to where it was at the start of last year. you should presumably think that any monetary policy effects on house prices will also be short-lived. The Bank however – not noted in this paper, but quietly in MPSs and FSRs – thinks the biggest long-term issue is land use law. If so – and assuming such regimes influence expectations and how markets react to demand shocks – they shouldn’t be taking responsibility themselves for higher house prices. Lets have some analysis on the distributional effects of land use restrictions, but you wouldn’t really expect that to be coming from the Reserve Bank – or for the Bank somehow to be taking the blame for medium-term changes in a key relative price (as it seems to by implication in, for example, the brief discussion of Figure 6).

Perhaps worse, there is almost no mention in the Analytical Note as to how the characteristics of the initial adverse shock might influence conclusions, and very little mention (I think only one) of counterfactuals – what might have happened if, given the neutral rate, monetary policy had done nothing in response to these shocks. For example, even just to take house prices again, in the last New Zealand recession house prices fell quite a bit, and if discretionary monetary policy actions limited those falls – as seems plausible and likely, directly and indirectly – I guess one think of monetary policy making home owners “richer”, but really it is simply limiting losses in those specific circumstances. And strangely there is no mention of any of the past actual monetary policy cycles in New Zealand – lots of high level handwaving but not much engagements with the specific experiences. Same goes for share prices – in this episode they are higher than they were at the start but in, say, 2008/09 it took five years for the nominal NZSE50 index to get back to the pre-recession peak. Monetary policy limited losses – in much the same way it did in the labour market – but that generally isn’t regarded as troubling, so much as the point of having the tool in the first place.

In a New Zealand context in particular, it was very odd to see no discussion of the exchange rate. In most discretionary monetary policy cycles in New Zealand, the exchange rate has done a lot of the adjustment (down and up). Over the last year or so that hasn’t been so – then again, monetary policy hasn’t done much – but surely any serious discussion of distributional effects of monetary policy in New Zealand would want to think about the exchange rate channel?

One could go on. For example, they suggest that older people are wealthier than younger cohorts, and while perhaps that is conventional it takes no account of human capital (by far the largest source of lifetime wealth for most people). And although they do talk about the labour market and unemployment it is all curiously bloodless – involuntary unemployment is a great social evil and can scar the prospects of some people for life, and so if – as it claims – monetary policy can assist in getting unemployment back down more quickly to the structural rate (while keeping inflation in check), that is a huge gain that a central bank should be shouting from the rafters, not burying in a discussion that seems overwhelmed by what has happened to house prices – monetary policy or not – in one recession in five.

Perhaps in fairness to the Bank one should repeat a couple of their concluding remarks.

In the absence of formal empirical evidence, we emphasise that we do not take a stance on how monetary policy actions by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand influence these distributions.

While noting that they could have done much more in these document to help frame discussion of the issues. And

The study of the distributional effects of monetary policy in New Zealand remains an avenue for future research. This Note is the first in a series of analytical papers that the Reserve Bank will publish in this domain.

I guess I will look forward to any future papers, but this scene-setting Analytical Note doesn’t leave one very optimistic about the overall quality of what they are likely to come up with. We deserve better: the Bank has the largest collection of macroeconomists in the country, its claim to operational autonomy really rests on perceptions of technical expertise, and yet – for what are not remotely new issues – so far this seems to be the best the Orr Bank can come up with. It simply isn’t good enough.