Ten days or so, prompted by the news emerging from China, I’d gone and found the pile of books I’d accumulated – and in many cases not read – over the years on pandemics, plague etc etc. Since then I’ve read three of them, including two on the 1918 flu pandemic.

The first, published in the 1970s, was Richard Collier’s The Plague of the Spanish Lady, a week by week treatment, drawn from some mix of contemporary accounts and survivors’ memories, of the experience with the flu pandemic (which got associated with Spain, mostly because Spain wasn’t at war and so there wasn’t the press censorship there was in many other countries). It isn’t a global perspective, but he captures accounts from across the Anglo countries and northern Europe – with quite a surprising number of snippets from New Zealand (the author apparently got a good response here when he advertised for survivors’ memories). It isn’t an analytical treatment by any means – there are various other good books for that – but it was an absorbing impressionistic read.

Someone asked me the other day whether it was “scary”, and I guess in a way it was. But I was more struck by the complex mix of responses, individual and institutional. At the official level, often a reluctance to disrupt the ordinary course of business, life etc – all compounded by the fact that there was still a war on. It is always difficult to tell whether, in its early stages, something will turn really serious, and to judge best which risks to run. But if those sorts of errors were pardonable, others were almost inexcusable – the French Governor of Tahiti, and the New Zealand Administrator in western Samoa being just two prominent examples. There are stories of sheer horror – an Eskimo village in northern Canada where many human victims were finished off, and dead human bodies eaten, by ravenous dogs that no one was well enough to feed – but also those of immense personal sacrifice, of people – professional and otherwise – rising to the occasion in ways they themselves might never had imagined, and so on. And there was the sheer number of deaths in a matter of weeks – New Zealand lost half as many to the flu in little more than a month than we’d lost in four years of World War One. Western Samoa is estimated to have lost 22 per cent of its population (while American Samoa lost no one).

The second was Prof Geoffrey Rice’s Black November: The 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand. I was reading the 2005 version, but there is a new, and shorter, version still in print. Rice – an academic historian – records that he had known nothing of the pandemic until he had an after-dinner conversation in 1977 with his father, who’d been a child in Taumaranui in 1918 and whose grandmother had been the final death in that unusually severely-affected town (if I recall rightly, around 80 per cent of Taumaranui’s population had come down with the flu and almost 2 per cent of the population had died (the national death rate was under 1 per cent). That conversation sparked Rice’s interest, and a sustained research project, culminating in a first edition of his book in 1988.

The more formal side of the book was built on a reassessment of the death toll, based n a careful examination of all New Zealand death certificates during the period of the flu (the advantage of a small population). The book includes the detailed data by suburb (and town/county) – 18, or just under 0.5 per cent, in Island Bay for example. And the data is there too (and a whole chapter of the text) for the staggeringly bad Maori death rate (4.2 per cent of the population died), although as Rice notes even in other years the Maori flu death rate far exceeded that for the European population up to at least the 1930s.

A significant chunk of the text is three chapters on each of the Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch/Dunedin experiences – city death rates (especially Auckland and Wellington) were consistently above those in the rest of the country – but there is a selection of detailed small-town accounts too (more than I’d ever previously read on Temuka). The book is liberally illustrated – photos, charts, and various survivors’ accounts (Collier providing his full New Zealand material) – and a nice mix of the more-analytical and the impressionistic/anecdotal. I’d strongly recommend it to anyone interested in the period. There is much the same mix of impressions – positive and negative- as in the Collier book, but with more space and a single country, more depth and insight.

There was the New Zealand Ministry of Health with a grand total of about 11 staff. A Minister of Health – George Russell – who was initially sceptical but then energetic, hard-driving, and pretty effective, even as he got offside with numerous local authorities. There was the heavy community engagement in many places – including an important role played by, for example, Boy Scouts in delivering messages, meals etc – but Rice highlights the difficulty local organisers had in finding enough volunteers to help in Wellington (life still going on, the mayor had lamented seeing various young and fit people playing tennis one weekend, even as the pandemic raged). There were doctors who gave everything and others who wanted only to tend their own patients. There was the extreme – but shortlived – commercial disruption, even a week-long “bank holiday” (for all banks other than the Post Office, which apparently attracted more deposits that week). There was the university exams suspended – it was November – after one student died while sitting his exam (the Chanceller of Victoria, former Prime Minister Sir Robert Stout, was outraged at the Minister of Health interfering in the internal affairs of the university). The residents at Te Araroa who, collectively, got out their shotguns to prevent (anyone who might carry the) disease entering their settlement. And the deaths, so many deaths. And the funerals – elaborate funerals and funeral processions being a more important element in society then. And perhaps in a testimony to some bits of government working better and faster then, the epidemic had only run its course in New Zealand by mid-December 1918, but the Epidemic (Royal) Commission’s report was presented to Parliament on 13 May 1919.

(Oh, and for those marvelling at China’s ability to build a new hospital in a week, I even noticed a couple of references in Rice’s book to small New Zealand towns – with limited people and technology – building new hospital wings in a matter of days.)

That’s enough history for now.

Ten days or so ago I also wrote a post, almost entirely hypothetical at time, about pandemics and potential economic effects when/if there ever were a serious one again. Much of it had just drawn on thinking I’d been part of back in the 00s when there was a major official government effort to prepare against the risk of pandemic (H5N1 being around at the time). But as I noted then – it was the standard view in that earlier planning exercise

….in a modern economy a serious pandemic could have major economic consequences, less because of the loss of life itself (although the loss of 1 per cent of the population would, all else equal, lower potential GDP semi-permanently by around 1 per cent) than because of the disruption, the fear, and the voluntary or semi-compulsory social distancing that would be put in place to try to minimise the risk of the virus spreading or of particular individuals contracting it. In a quarter in which an outbreak was concentrated, it is quite conceivable that GDP could fall by as much as 20 per cent (if every worker was off work for just a week – whether sick themselves or caring for others – and that was the only adverse effect – it wouldn’t be – that alone would be a loss of almost 8 per cent). Even if the outbreak was quite concentrated in time and normal economic activity resumed in full very quickly, in such a scenario GDP in the year of the outbreak would be 5 per cent less than otherwise.

Ten days on, that must be a lot like what is going on in Wuhan – and, it seems, an increasing number of Chinese cities. Read the stories, watch the video footage etc and it is hard not to suppose that GDP in these parts of China will not be very very sharply lower in the first quarter (whatever the official statistics eventually say). And all that with “only” 17000 offically confirmed cases – that is a lot of people in absolute terms, but a tiny share of the population relative to (say) 1918 or those earlier pandemic planning scenarios. There are doubts among some experts as to whether the PRC numbers are being properly collected/reported, but whether that is so or not, the economic effects (in large chunks of one of the world’s biggest economies) are already looking real and substantial.

And that is just China. What about here, where there has not yet been a confirmed case? We already had some direct effects last week (on the small scale, crayfish exporters and on the much larger scale, the PRC authorities themselves banning any outbound tourism (booked through official agencies, but we are told that is most of it)). And non-trivial numbers of people wouldn’t have been able to travel anyway because they were locked down in their own cities or even neighourhoods in China). But now we have joined a range of other countries in banning entry to non-citizens who had been in China in the last 14 days. Probably the Chinese students coming for secondary school were mostly already here – the treasurers of the respective boards of trustees will be grateful for that – but the university year is still several weeks away and there are normally lots of PRC students (new ones, and ones returning after the long break). For the time being none will be arriving.

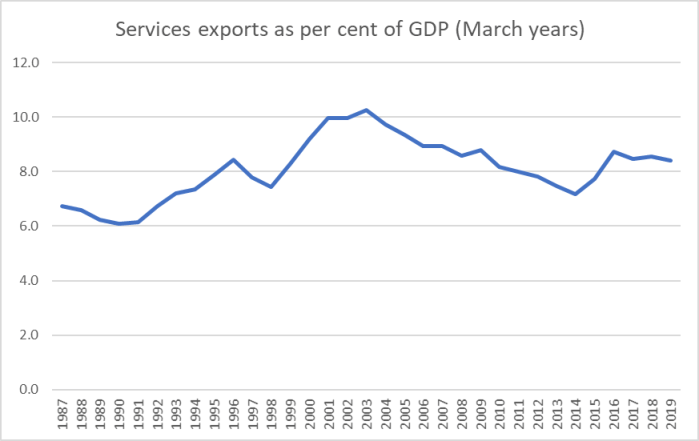

Despite the idle government talk – unquestioningly repeated by most of our media – there seems very little chance that this ban will be only for 14 days. It wouldn’t take that long presumably before, even if the ban was lifted, it wasn’t worth coming for the rest of the first semester. There is a lot of revenue at stake for most of universities (and plenty of other tertiary institutions). Tourism and export education receipts from the PRC alone make up 1 per cent of our economy – direct effects only. Once this is all over it would be interesting to launch a series of OIAs to discover how much education sector lobbying of the government was going on last week – “never mind about public health risks, think about our bottom line”, and if you think that is excessively cynical, recall that this is basically the approach our universities take to the PRC more generally (“don’t expect us to be critic and conscience, there are joint ventures to be done, revenues to raise”).

(As it happens, this episode looks like an interesting quasi case study on PRC issues more generally. In writing about the appalling way our political classes pander to the PRC, I have pointed out that export education and tourism are the two sectors that are most vulnerable – commodities are sold in a global market. One could envisage the PRC “punishing” New Zealand if it ever chose to speak out and push back more seriously – has happened to other countries – but probably the most severe scenarios wouldn’t have envisaged PRC tourism and export education revenues being shut off almost completely overnight. These will not be trivial effects, but I’ve argued that we could expect exchange rate adjustment and monetary and fiscal policy offsets, and that in the event of any such “punishment” it would not in any sense be catastrophic for the New Zealand economy, tough as it might be for individual over-exposed firms. Time will tell how this particular unfortunate “experiment” plays out.)

It is very hard (for anyone) to know what the right policy response for countries like ours (or the numerous others that have imposed similar restrictions) might be. You could mount a fairly good case, I’d have thought, for putting in place these sorts of restrictions a week ago – after all, the Chinese authorities are the ones with the only real and hard information and they’ve imposed unprecedented lockdowns and stopped their citizen tourists going abroad (the latter arguably a very public-spirited approach to the rest of the world). The revealed preference signals were pretty strong, and have only got stronger as the week has gone on. You might also be troubled – as I’ve been – by the small number of cases the PRC is reporting completed and discharged. The WHO might not approve of restrictions – appears still not to – but the WHO is responsible to no citizens or voters. But our government was almost entirely silent all week – nothing at all from the PM, little or nothing from the Minister of Health and mostly sunny upbeat stuff from the Director-General of Health and his staff. They seemed to think this wasn’t a matter they needed to engage seriously on, and the media seemed to not pursue the issue in any meaningful way.

There were telling comments in an (otherwise strange) interview on Radio New Zealand this morning with the PRC Consul-General in Auckland. Having taken the lead in banning its own people from heading abroad as tourists, the PRC now appears to have got grumpy at countries imposing their own restrictions. The Foreign Minister has been quoted criticising the US restrictions. And here is the Consul-General (and recall this is an agent of a highly authoritarian state, he won’t going off-message or talking out of school).

The Chinese people are now isolating the coronavirus, but New Zealand is … joining efforts to isolate the Chinese economy. That’s why I feel very disappointed.

“I think the epidemic will certainly have a impact on the business between the two countries. China is New Zealand’s largest trading partner … as I said before trade should be based on a normal exchange on people. But this sudden travel ban will worsen the current situation. If Chinese economy suffers from international isolation, the New Zealand economy will also be in a loss.”

No one here is trying to “isolate the Chinese economy”: rather our authorities are simply doing what the PRC had already been doing. You and I are free to buy stuff from China: the big question this week is how many Chinese factories or offices will be actually at work. If China is suffering, it is from a virus that got started in China (and which was covered up initially be the Chinese authorities).

But my real interest was in the Consul-General’s comment on the New Zealand government

“I can tell you that only two days ago, our foreign ministers talked over the phone about the outbreak… Foreign Minister Winston Peters said that New Zealand will maintain normal exchanges and people’s flow between the two countries. However, just overnight, the New Zealand changed its mind.

Now that is very interesting. It suggests that as recently as Friday or Saturday our deputy prime minister – presumably reflecting whole of government policy – was telling the Chinese Foreign Minister that we would be imposing no travel restrictions. I suppose the PRC could have got the wrong end of the stick, or be misrepresenting the conversation, but someone should surely be asking Winston Peters some hard questions about just what went on the inner counsels of our government (all this apparently without a Cabinet meeting).

Because suddenly yesterday afternoon we were imposing travel restrictions, much the same of those imposed by various other countries – against WHO preferences apparently – a day earlier. The notable late movers were the United States and Australia.

One has to wonder what the New Zealand government learned in the 24 hours prior to yesterday afternoon that led to such an (apparently) sharp change of stance. I wonder whether pressure was put on them by the Australian government? One could imagine the Australians thinking “well, if we put on restrictions and New Zealand doesn’t, the virus could get established there, and with incubation periods etc that would allow backdoor entry to Australia. “Nice visa-free entry to our country you have there: shame if something got in the way of it” might have been the message, express or implied. Perhaps someone might ask our government, or Australia’s.

(Having imposed the restrictions, I presume the government is now thinking hard about what criteria it would use in deciding whether to extend the ban to people who’ve been in other places. Will 100 human-to-human cases in Australia, or Hong Kong, or the US, or the Philippines, be enough for a ban on people having visited those countries. If not 100, then how many? I don’t know the answer, but I hope the government has one in mind.)

And an almost-final thought for now, I’ve been staggered at how poor the New Zealand media coverage of these issues – as they directly involve New Zealand policy choices – has been. It is easy to run foreign stories on events in China, but what we also need is seriously reporting and scrutiny of choices made, risks run (or averted here). Last week, our media seemed simply engaged in channelling Ministry of Health lines, and a few personal stories. In today’s media there still isn’t much sign that anyone has done any digging, talked to inside sources etc, to understand the dynamics of government decisionmaking. And there is hardly any mention – I saw one very brief snippet in the Herald – of the economics of the tertiary education sector, no attempt to talk to vice-chancellors, no attempt to talk to other commentators. (Not even any apparent attempt to talk to the China Council, who must be torn – when David Clark says the Chinese authorities were relaxed about NZ government choices, and the Consul-General says the opposite). And there has been no serious challenge or discussion on the “14 day ban” – which seems to risk giving quite misleading signals to people in relevant industries, against a global backdrop where unease is increasing, not showing any sign of relief).

And a final purely anecdotal point. I was staggered over the weekend to hear of two teenagers, one of whom was reluctant to go into central Wellington over the week for fear of being exposed to coronavirus, and another whose parents forbade her to go. And then this morning I was in the supermarket and noticed a customer in front of me (as European-looking as me) coughing her way down the aisle, not covering her mouth at all. I suspect at another time I wouldn’t even have noticed, and yet I was brought up short – not because I have any unease at all about being out and about anywhere in New Zealand, but in realising what the recent news had made me take notice of. One has to wonder how much self-initiated social distancing will start going on here. It doesn’t take much – rational or not – to put a dent in entertainment etc spends.