According to the IMF these are the countries that will have an inflation rate in excess of 20 per cent this year.

| Turkey | 20.3 |

| Liberia | 27.2 |

| Yemen | 30.0 |

| South Sudan | 40.1 |

| Zimbabwe | 42.1 |

| Argentina | 47.6 |

| Islamic Republic of Iran | 51.1 |

| Sudan | 72.9 |

| Venezuela | 1555146.0 |

I’m guessing there is some margin of error around that curiously specific estimate for Venezuela.

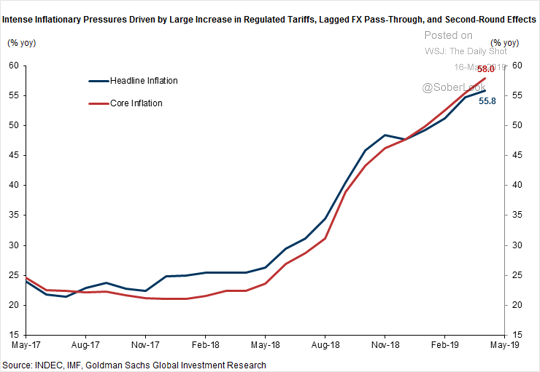

In most of these countries, inflation is forecast to be higher this year than it was last year. Here is one stark example.

It can be done – although one might well wish to avoid the Argentine experience.

On the other hand, the IMF also forecasts that there will be 13 countries with 2019 inflation rates of 0.5 per cent or less. (The median inflation rate across all countries this year is expected to be 2.4 per cent.)

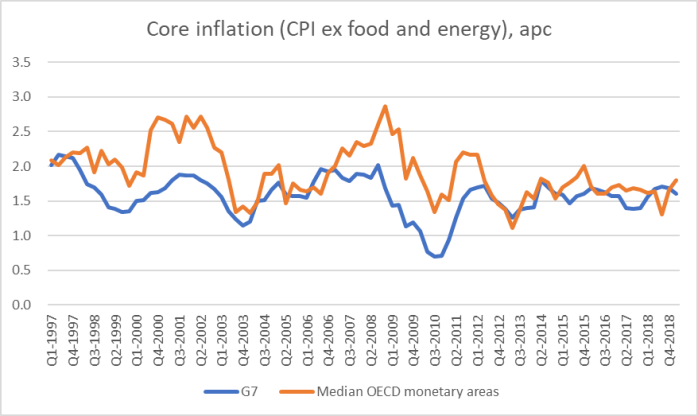

In the advanced economies there isn’t much sign of any rebound in (core) inflation

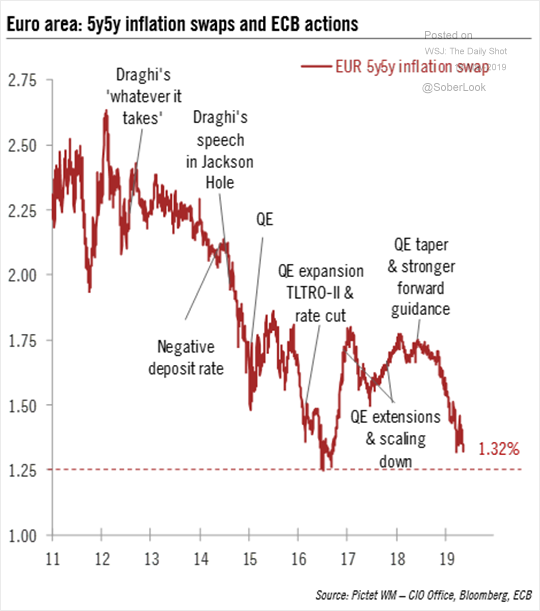

What about expectations? Bond yields are falling again, and not all of it seems to be falling real rates. Here is a chart I saw yesterday showing implied five year forward expectations for average inflation in the euro-area.

That is a long way below 2 per cent.

Things aren’t as bad in the US. Here is the latest chart for 10 year inflation breakevens.

And in both Australia and New Zealand the gap between indexed and conventional government bond yields is not much more than 1 per cent. That is a long way from the 2.5 per cent and 2.0 per cent targets respectively.

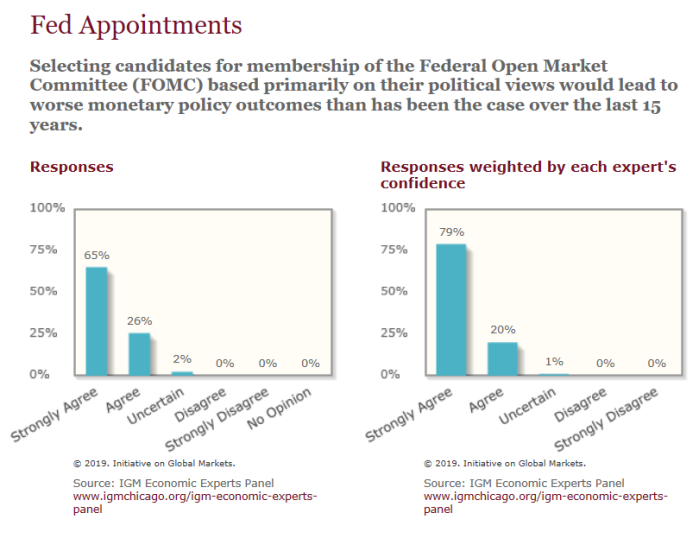

This was a bit of context for the last IGM survey of economics academics that I saw the other day.

I guess the question was asked in the specific context of the aborted nominations of Stephen Moore and Herman Cain, but it is posed more generally.

I’d probably have answered the same way, especially bearing in mind the way the question is phrased (note that “primarily”). Apart from anything else, choosing anyone for anything primarily based on their political views is a recipe for trouble (even in Cabinet or the organisational side of a political party one usually wants competence as well).

And yet, and yet. It is hardly as if the actual monetary policymakers in much of the advanced world have done such a great job in the last decade that things couldn’t have been improved on. Arguably, the US Federal Reserve has done better than most central banks, but even then it was hardly a record to write home about (slow to recognise the recession in the midst of it, constantly champing at the bit to tighten afterwards, nothing done to prepare for the next serious recession etc).

When I was young the predominant narrative around central banks was that one needed to keep politics and politicians clear, because otherwise high inflation would be a recurring – perhaps permanent – problem. I’ve long been fairly sceptical of that view, even as an explanation for history during the Great Inflation, but look at where we’ve been for the last decade, with inflation sitting below target in most advanced countries even as unemployment was (for a long time) slow to fall. It isn’t impossible that in those specific circumstances (even if not generally) monetary policy decisionmakers with a stronger political focus might have done less badly than the actual decisionmakers did. That, at least, should have been the out-of-sample forecast of the more vocal champions of technocratic rule if this argument had been run a decade ago. (Of course, political bias can cut both ways: there have been both technocrats and politically-attuned people on the right in the last decade championing the case for higher interest rates, arguing that if anything raising interest rates pre-emptively might assist in rebalancing the economy.)

I’m not arguing to junk professional expertise when it comes to monetary policy, any more than one should in any other area of policy, but in and around monetary policy the limits of technical expertise are pretty real and substantial (or we’d have easy compelling and generally accepted answers to the issues of the last decade) and it isn’t obvious that professional experts are necessarily the best final decisionmakers. In the face of great uncertainty, I’m increasingly inclined to think that the decisions should rest more squarely with those who are electorally accountable – drawing on professional expertise to the extent it can help, but recognising the need for contest, scrutiny, and considerable scepticism about the best insights of institutional “experts”. In that world, central bankers provide analytical inputs, and operational implementation of policy choices, but have less weight in the policymaking itself.

In a New Zealand context, it was sobering to read the other day that the UK statistics office had just announced that the British unemployment rate had fallen to the lowest rate since 1975 (and the US unemployment rate is the lowest since 1969), without inflation having become an obvious problem. In New Zealand, the unemployment rate in 1975 was about 2 per cent. Just to get back to the lowest unemployment rate this century in New Zealand we’d need to see a drop of another 0.9 percentage points. In view of our central bank’s statutory mandate around “maximum sustainable employment” it would be interesting to see their analysis of why we can’t manage something like that. Perhaps there are regulatory or welfare obstacles (eg high minimum wages relative to median wages) – and if so, central banks can’t do much about those – but with inflation still persistently a bit below target, it sure looks as though New Zealand’s unemployment rate could be a bit below 4.3 per cent without creating inflationary trouble.

Is unemployment rate a fuzzy measure that must be difficult to compare country by country? There are people who might choose paid employment but are happy collecting a pension. My severely disabled neighbour needed two permanent carers – she would not count as unemployed but permanently disabled from birth but the same concept of unfit to work applied to many Brits when I lived there – it was easy then to get a doctor to declare you unable to work; you received the same benefit but without the hassles of pretending to look for work and the benefits office was happy to see the back of you; it left Britain as the most disabled country in Europe. There are varied retirement ages in different countries. Short term and long term unemployment are very different but a single statisitic does not distinguish them. There are varied incentives to work which change from country to country: benefit levels and minimum wage rates. And the subsidising of tertiary education acting as a sponge for young unemployed. There is a similar issue with the concept of being ‘under-employed’ which also covers many different situations.

My guess: you can’t compare unemployment rates from country to country nor from now to the past when the nature of society and work was different. It is a useful measure for following trends.

Inflation: I have tried but cannot grasp why it is low now and was high forty years ago; I can understand Venezuela and Zimbabwe’s woes caused by printing money but have trouble applying the same to developed countries with minimal corruption. Relativity (subject of discussion at my U3A) is far easier to understand than money and its value. With relativity I partly grasp the lorentz contraction, etc and then I trust the experts because relativity is required to keep GPS systems working. With money we have to trust economists. In Nov 2008 during a briefing by academics at the London School of Economics on the turmoil on the international markets the Queen asked: “Why did nobody notice it?”.

LikeLike

There are fairly standardised measures of unemployment: did not do paid work in the reference week, are actively looking for a job, and are ready and willing to start next week if you could get a job. In NZ’s case, the HLFS series is pretty consistent back to 1985, and an academic has published backdated estimates for earlier decades.

I wouldn’t put any weight at all on a comparison that UK unemployment was 4.5 and ours 4.3, but that our rate is still higher than it was in 2006/07 while the UK’s is lower than it was does look like a meaningful comparison (starting point for asking questions).

LikeLike

I’m of the opinion that central bankers are acting the way they because that is how politicians want them to act. That is politicians, above all else, don’t want to take responsibility for anything so they are encouraging, or at least not discouraging, central bankers from taking executive decisions about what the inflation target should actually be. This also explains the various other functions they have taken on that are not in the direct remit of money supply management (which is the only part that I think needs separation from direct political influence).

LikeLike

RBA Monetary Policy Committee has a lot of industry representation on it. They seem to have undershot their target slightly, but have done a good job for the past 2.5 decades on the whole.

LikeLike

I’d give the RBA very good marks for the first 20 years of that period, but less so during the Lowe years. It is still an impressive institution in many ways, but the bottom line – trimmed mean inflation relative to the target – is becoming an increasingly obvious blackspot. They seemed to fall into the RBNZ trap – hankering to tighten, while ignoring for too long the weakness of demand. That said, they make their mistakes more eloquently and authoritatively than their NZ counterparts.

LikeLike