The latest GDP numbers for China were released yesterday. If they probably got more attention than they deserved in the international financial media, there appears to have been no coverage at all in the two main New Zealand newspapers – surely there is some sort of happy median, as regards one of the two biggest economies in the world, one of the two economies with which New Zealand firms trade the most? There has long been a sense that the PRC’s statisticians smoothed the national accounts data for political purposes, but in recent years there has been a growing sense that many of the numbers are, to a greater or lesser, extent, just made up. Among the straws in the wind has been the remarkable stability in the reported GDP growth rates over the last few years.

More recently still, there has been a growing disconnnect between the reported GDP numbers and perceptions on the ground. Here is how Michael Pettis, a leading analyst of Chinese economic developments and professor in Beijing, put it a few days ago

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s economic growth in every quarter last year exceeded 6.5 percent. While that is much lower than the heady growth rates China has experienced for most of the past forty years, it is still, by most measures, a very brisk rate of growth.

And yet, when you speak to Chinese businesses, economists, or analysts, it is hard to find any economic sector enjoying decent growth. Almost everyone is complaining bitterly about terribly difficult conditions, rising bankruptcies, a collapsing stock market, and dashed expectations. In my eighteen years in China, I have never seen this level of financial worry and unhappiness.

“Perceptions” don’t help much in working out whether an economy really grew at 6.5 per cent or 6.2 per cent, but those aren’t the sorts of differences people are worrying about.

But what prompted this post wasn’t yesterday’s GDP release but rather finally getting round over the weekend to reading the translation of a speech given last month, marking the 40th anniversary of the PRC’s economic liberalisation, by a prominent Chinese economist. It is introduced this way

On Dec. 16, Prof. Xiang Songzuo (向松祚) of Renmin University School of Finance and former chief economist of China Agriculture Bank, gave a 25-minute speech during a CEO class at Renmin Business School that was apparently applauded by the audience but immediately censored over the Chinese internet. Singling out 2018 as the year when China comes to a large shift unprecedented over the past 40 years, the speech can be seen as a landscape survey of Chinese economy, and obliquely, also of politics. Just as Tsinghua law professor Xu Zhangrun’s (许章润) broadside “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes”, which was superbly translated and widely talked about among China watchers, Prof. Xiang’s speech is another rare burst of Chinese intellectuals’ discontent with the direction the country is taking under Xi Jinping.

He begins with the economic slowdown

China’s economy has been going downward this year, as everyone knows. The year 2018 is an extraordinary year for us, with so many things taking place. But the main thing is the economic slowdown.

How bad are things? The number that China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) gives is 6.5 percent, but just yesterday, a research group of an important institution released an internal report. Can you take a guess on the GDP growth rate that they came up with using the NBS data?

They used two measurements. Going by the first estimate, China’s GDP growth this year was about 1.67 percent. And according to the other calculation, the growth rate was negative.

(These latter suggestions were reported last month.)

It is a remarkably forthright speech. For example

Second, what was the cause for the economic downturn? Why did private enterprises suffer setbacks in 2018? Looking at the data, investment by private businesses has dropped substantially, so what made private business owners lose confidence? On November 1, the national leaders convened a high-profile economic conference, which some interpreted as a signal that the government wants to win back the confidence of private businesses as the economy worsens.

Since the beginning of the year, though, all kinds of ideological statements have been thrown around: statements like “private property will be eliminated,” “private ownership will eventually be abolished if not now,” “it’s time for the private enterprises to fade away,” or “all private companies should be turned over to their workers.” Then there was this high-profile study of Marx and the Communist Manifesto. Remember that line in the Communist Manifesto? Abolition of private property. What kind of signal do you think this sends to private entrepreneurs?

Or

When we buy stocks, we are buying the profits of the company, not hype and rumors. I recently read a report comparing the profits of China’s listed companies with those in the U.S. There are many U.S. public companies with tens of billions dollars in profits. How many Chinese tech and manufacturing companies are there that have accomplished this? There is only one, but it’s not listed, and you all know which one that is. [Xiang is referring to Huawei, the Chinese tech company.] What does this tell us? As Yale professor Robert Shiller said: stock market performance may not work as a barometer of the economy in the short run, but it does for sure in the long run.

So I think that the terrible stock performance only demonstrates one thing, which is that the real economy in China is in quite a mess. Where is the stock market rebound? I think it’s obvious that investor confidence has yet to recover.

Or

I’m acquainted with many bosses of listed companies. Frankly speaking, a large part of their equity pledge funds did not go into their primary business, but used on speculation. They have many tricks. They buy financial products; they buy housing. The government said listed companies have spent 1-2 trillions on speculative real estate. Basically China’s economy is all built on speculation, and everything is over leveraged.

Starting in 2009, China embarked on this path of no return. The leverage ratio has soared sharply. Our current leverage ratio is three times that of the United States and twice that of Japan. The debt ratio of non-financial companies is the highest in the world, not to mention real estate.

Macro policies can be short-term palliatives, but they don’t deal with the basic issues

Moreover, these credit and monetary policies can only make short-term adjustments that are incapable of fundamentally solving the “imbalances” I mentioned earlier. We are still trapped within the box of the old policy and the old way of thinking. The key to whether transformation will be successful is the vitality of private enterprises—that is, whether policy can stimulate corporate innovation.

We have been making a game of credit and monetary tools for so many years. Isn’t this the reason we are saddled with so many troubles today? Speculation has driven housing prices sky-high.

Ending thus

I hear that the day after tomorrow, there’s going to be a grand conference to mark the 40th anniversary of the “reform and opening up.” I sincerely hope that we’ll hear something about further deepening of reforms at that conference. Let’s wait and see if any real progress can be made on these reforms.

If this doesn’t happen, let me conclude on these words: the Chinese economy is going to be in for long-term and very difficult times.

In some ways, what has been remarkable about China over the last year is that not only has there been no serious structural reform (of the sort that might actually position the economy to get towards material living standards in places like Korea, Japan, Taiwan or Singapore) but there has not been much counter-cyclical stimulus either.

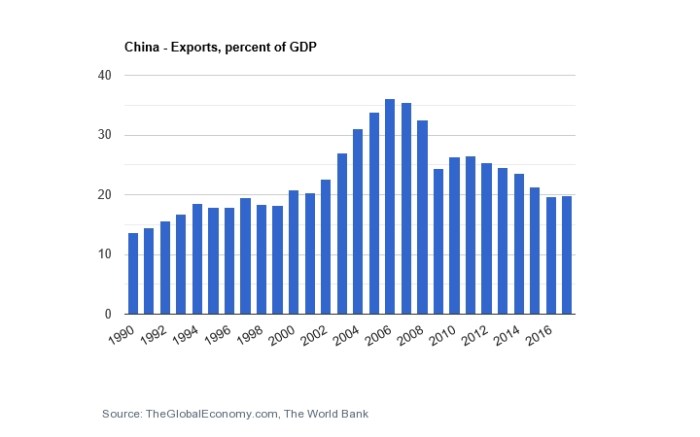

If one takes a highly stylised view of China’s economic growth this century, there are two broad phases. The first involved a huge increase in China’s exports, and in the export share of China’s economy.

From 2000 to 2007, exports as a share of (fast-growing) GDP rose from around 20 per cent to around 35 per cent (imports also rose substantially, but this was the period when the current account surplus – in a developing country – peaked at almost 10 per cent of GDP). Of course, not all of that was value-added by Chinese firms – many products are recorded as final exports from China, but may only have a relatively limited amount of Chinese value-added in them (i-phones are the most often-cited example). In a country as large as China, trade shares anywhere near 30 or 35 per cent were never going to be sustained – large countries (see the US or Japan) mostly trade within their own borders – and with the sharp rise in China’s exchange rate, and the slowdown in growth in demand from advanced economies, the “export engine” has lost power. In fact in USD terms China’s exports have grown only quite modestly over the last five years (and consistent with that the export share of GDP has shrunk markedly).

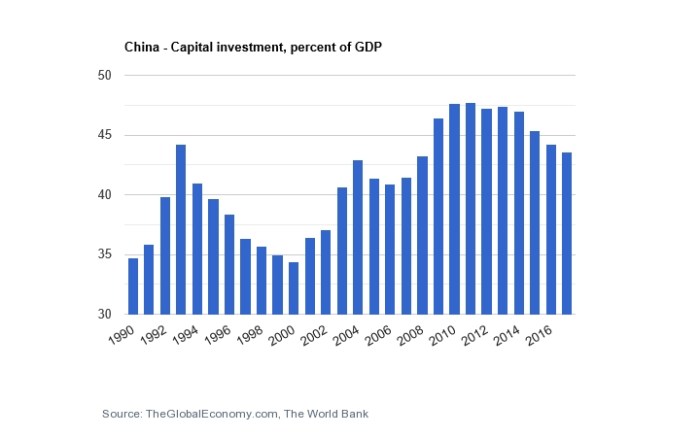

After 2008, GDP growth has been underpinned by a massive domestic credit and investment/construction boom.

During that period, investment of GDP – already absurdly and inefficiently high – reached new highs, in an economy that had neither strong population growth nor, any longer, was making big new inroads competing in world markets. You can do that sort of thing for a while – on a much smaller scale, one could think of the Think Big massive boost to recorded investment and activity here in the early 1980s, or of the construction booms in Spain and Ireland earlier this century. But the economic returns to doing so tend to be quite severely diminishing, and the risks (associated with sustained misallocation of resources) mount. It seems to take more and more additions to credit to get the next dollar increase in GDP. And private borrowers/investors – even aided and abetted by over-eager lenders – get more uneasy, and only the most risk-loving are still keen to take on new projects. To the extent that GDP still rises, productivity rarely does. Excess capacity forms, even as the most deluded fails to recognise the symptoms,

Indications are that the Chinese authorities recognise that the credit boom and associated wasteful investment wasn’t sustainable, but there also seems to be a possum-in-the-headlights dimension to policymaking at present. What are the feasible alternatives after all?

For a long time, my approach to China was that of course the state could prevent a financial crisis (of the sort in the US in 2008/09) if it chose to. After all, there are few technical obstacles to a totalitarian state just guaranteeing all the liabilities of banks and other financial institutions. Perhaps they still could, although the complex web of channels of financial intermediation – combined with starting levels of debt and deficits – make that a lot harder than it once was, and even guarantees don’t allay all the fundamental unease about the misallocation of resources and associated risks (you might not panic – running on your bank – but you might be reluctant to invest or spend anyway).

Conventional mechanisms in a market economy rely heavily on cuts in official interest rates. Chinese interest rates could be cut, but (a) the transmissions mechanisms aren’t the same as those in market economies, and (b) as we saw in the West after 2008, even big cuts in interest rates can – when times are tough – often only act to lean against the depth of a recession, not necessarily doing much to put growth on firmer sustained foundations.

There is fiscal policy of course. Given the China is already starting from a deficit position (on OECD numbers, Chinese government net borrowing as a per cent of GDP is projected to be about 3.5 per cent of GDP next year) perhaps the possibilities there are more limited than they might seem, especially against the magnitude of the slowdown China seems to be experiencing. But – and these are the sorts of options we used to debate in western economies when we thought about the exhaustion of conventional instruments – there is always, at least in theory, the option of large scale directly government-financed construction and related projects: unsterilised fiscal policy, directly financed by the central bank: building bridges to nowhere, more empty apartments, airports that are little used and so on. It could be done no doubt, although simply freeing up liquidity requirements and encouraging banks to lend isn’t likely to bring such outcomes about. And PRC technocrats seem as uneasy about unconventional macro policy as many of their western counterparts were (it is, after all, only 70 years since China was experiencing hyper-inflation). But even if it were done, it would have the feel of simply buying time, storing up bigger adjustment problems further down the track.

The other strand of a conventional transmission mechanism involves the exchange rate. Economies experiencing difficulties will typically experience an exchange rate adjustment, which lifts returns to domestic producers, encourages more investment in the tradables sector, and so on. It was one thing for China to engage in a massive domestic-focused credit boom starting from a position of a 10 per cent current account surplus (and massive – relative to the then size of the economy – foreign exchange reserves). It is quite another now, when (a) the current account is near balance, (b) reserves are at unspectacular levels, and (c) the private sector seems increasingly distrustful. Significant fiscal or monetary stimulus will, all else equal, boost domestic demand but not foreign demand, and would increase materially the pressure for an exchange rate adjustment (and the perceived returns to illegal capital outflows). That would be rational and sensible adjustment in a normal economy – places like Greece and Portugal would almost certainly have benfited from having the option, as New Zealand does in its downturns – but it is nowhere near that easy an option for China, for economic and political reasons. Such a devaluation – let alone a float – would only intensify that economic conflict with the United States, but might well be seen more widely (at a time when the world economy is not strong) as exporting deflationary pressures to the rest of the world, and potentially bringing renewed global economic stresses (the amount of USD borrowing by Chinese entities is also not an irrelevant consideration).

This isn’t an attempt to offer all the answers, more about identifying some of (very real) constraints that PRC economic policymakers now face. I’m very much with the learned professor, quoted earlier, that what – in some abstract longer-term sense – China needs is serious thorough-going market-oriented reform and liberalisation. But even in small advanced economies those sorts of programmes can be very disruptive, even costly, in the shorter-term, whatever the substantial longer-term gains on offer. But in a society where the Party in charge has spent the last half-dozen years asserting increasing control, in an economy now one of the largest in the world (when the global economic environment is insipid at best), starting from all that debt, and in an increasingly tense global political environment how plausible is it to expect step-changes in policy for the better? And how credible would either domestic or foreign investors even regards indications of such change as being?

What might it all mean for New Zealand? The terms of trade is typically the main channel by which slowdowns abroad affect our economy, but one might reasonably be pretty nervous about the outlook if one were a New Zealand exporter of education services, construction products, or even (year of the Chinese tourist notwithstanding) tourism. Fortunately for us, we do have a flexible exchange rate and fluctuations in our exchange rate don’t matter much to anyone else, but don’t forget how little conventional monetary policy firepower even our Reserve Bank has now, compared to what it had in previous downturns.

To end with just a couple of snippets. This from the same Pettis commentary I linked to earlier

These concerns have even breached academia. One of my students told me yesterday that there was a huge increase last semester on the university website in the number of students selling their belongings because they are hard up for cash. They are selling their phones, computers, clothing, and lots of other possessions. He said the amount of selling is noticeably higher than last year, enough so that everyone is talking about it. And he indicated that this is apparently happening at other schools too. It seems that the poor and middle-class kids are squeezed for cash because they are getting much less money from home than they have in the past. This isn’t what you’d expect to hear from an economy growing at more than 6.5 percent.

And this from a story I noticed over the weekend

“I’ve been a manager for almost half a century, but this is the first time I’ve seen such a large single-month drop in orders for us,” said Nidec CEO Shigenobu Nagamori. “What we witnessed in November and December was just extraordinary.”

Nidec, a Japanese company with $14 billion in revenues last year, makes a wide range of electric motors, from tiny devices that make the iPhone vibrate to industrial motors. It’s the world’s largest manufacturer of motors for disk drives. For the automotive industry, it makes things like engine and transmission oil pumps, coolant pumps, control valves, and fans and blowers. It makes motors for industrial robots, etc.

It’s a supplier to Apple, other electronics makers such as hard-drive makers, but also appliance makers, automakers, robotics manufacturers, industrial equipment manufacturers, etc. In other words, the company is a key supplier of advanced parts to Chinese factories.

The company slashed production at the end of 2018 for Chinese automakers and appliance makers by over 30% because of weak demand, Nagamori said.

This slowdown seems to be very real, and China is large enough now it is likely to really matter across the world economy. As my former colleague Kirdan Lees has it (in a column I don’t fully agree with, but might comment on in a separate post), Grant Robertson needs a recession plan. So does Adrian Orr. Not because such outcomes are certain – they never are (until it is too later) but because the risks are rising.

I’ve just read Ambrose Evans-Pritchard’s article in the Telegraph discussing Prof Ken Rogoff’s assessment that China’s “Minsky Moment” is near. (www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2019/01/21/moment-minsky-reckoning-may-finally-near-china-warns-banking/). Rogoff co-wrote the excellent history of financial disasters “This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly” (2009).

Rogoff is quoted as saying he sees China’s debt problems as “the third leg of the global debt supercycle, after subprime in the US and the debt crisis in the eurozone. Nobody knows how this is going play out but it could be on the scale of 2008 and it is will be very bad for Asia, and there will be spillovers in Europe.”

I assume NZ would be similarly hit as part of “Asia”…

LikeLike

Thanks. I think the issues are a bit different for much of Asia than they are for us, but if this happens no one will be immune to ther economic fallout (given the limited macro policy capacity in most of the world) and few will be immune to the likely political fallout – both things the PRC might do, or try to do, in response, and other collateral damage (eg I still reckon the end of the euro is likely in the next serious recession).

Here is link to a note I wrote a few years ago about how NZ might be affected by a serious Chinese slowdown

Click to access discussion-note-2014-what-if-china-slowed-sharply.pdf

My conclusion then was:

Whatever one’s view about the probability of a sharp slowing in China’s economy, if it were to happen over the next year or two it would represent a very substantial threat to the health of the world economy, at a time when it has few countervailing tools at its disposal, no coordinating devices, and little recuperative power given the existing debt overhang in much of the world, slowing population growth etc. The threat to the world economy, and its financial system, seems more likely to pose significant economic and financial threats to New Zealand than any direct impact from China to New Zealand. Those latter effects seem likely to be no larger than the normal swings and roundabouts a modern economy faces from year to year.

LikeLike

SkyCity hits record $169.5 million full year profit. The casino operator, SkyCity Entertainment, has reported a record full year profit as its New Zealand business improved, and its high rollers business recovered.

Group revenue was dominated by the flagship Auckland casino, where revenue rose 3 percent, while earnings in the international high rollers business rose 39 percent.

https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/business/363608/skycity-hits-record-169-point-5-million-full-year-profit

Looks like Skycity is benefitting from a China slowdown.

LikeLike

I don’t see how China can avoid a crisis. They’ve largely tapped out monetary policy already. Reserve money isn’t growing and they’re maintaining credit growth now by collapsing banks required reserves.

The current account is likely to move into deficit this year and capital flight remains massive. FDI and portfolio inflows aren’t going to be sufficient to fund the BoP so they’ll have to draw on reserves.

So the two binding constraints in the system are now operating; monetary and fiscal policy reaching their limit and the BoP deteriorating.

They’ve sustained the system through their own “think Big” and that’s reaching its limit.

LikeLike

I largely agree, altho one imponderable is the form any crisis takes, esp given the increasing Xi/Party emphasis on control, and the risks that anything remotely chaotic could play very badly with the populace.

LikeLike

Peter, Yuan interest rates is hovering around the 3.3% mark which is much higher than our 1.75%. How do you justify a comment that Monetary policy in China is largely tapped out? At 3.3% they still have to get to the zero bound interest rates before Monetary Policy is deemed to be tapped out?

LikeLike

They are ramping up Chinese Tourism

https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ninetonoon/audio/2018679050/tourism-industry-braces-for-china-2019

The bus in the photo is typical: Chinese owned and Chinese driven and you see them everywhere. Katherine Ryan quoted figures in the interview “tourism earns $38,000/ worker ; Apple about $1,000,000. You would think the dominance of Chinese migrants in our largest industry (plus the low pay) would be HUGELY embarrassing (however they don’t embarrass easily).

LikeLike

Could be 3rd generation Kiwi Chinese? They do all look the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps we should re-introduce the Chinese Migrant Poll Tax?

LikeLike

Getgreatstuff,

What you’ve got to understand is that China operates a hybrid monetary policy system in which they manage multiple tools. The main tools are quantitative, not price based.

The stock of outstanding credit can be managed through management of reserve money and banks’ reserve ratios. In the past five years the People’s bank has managed to stabilise reserve money despite a decline in net foreign assets, through massive OMOs. This has effectively acted like a de facto RRR cut. Problem is, reserve money growth has stalled and the scale of OMOs is running into limits. So the PBoC is slashing banks RRR to keep credit growth going. That’s unsustainable.

On the price side, you are correct in pointing out they have scope to cut the 7-day repo rate, although they’re unwilling to do so. I’ve been received and it’s rallied but I’ve closed my receive CNY ND IRS 1y1y position as of yesterday.

They can cut the official lending rates but this may or may not be passed on to businesses. And if they do cut then deposit rates will need to be cut, otherwise they run the risk or triggering deposit and/or capital flight. Given the state of the banking system and BoP these are real concerns.

So monetary policy has some room to move, but not much. And the risk is, they destabilise CNY.

LikeLike

That should read “and” they run the risk of deposit flight, not otherwise.

LikeLike

I think capital flight is being controlled by a 50,000 Yuan limit in terms of how much each individual can transfer out of the country without government approval. As far as i know those controls are still active.

LikeLike

….seems a solution rests with the US running twin deficits (again?) as I doubt China wants to run down her reserves just yet: so wonder who blinks first??

LikeLike

Niall Ferguson wrote in 2012 of how a deterioration in Chinese progression towards the rule of law would hurt her appetite for domestic investment. He predicted we wouldn’t get a Xi. He got that wrong, but seems to be right about the rule of law element.

LikeLike

Great piece, thanks for piece on the Japanese firm. Firms like Nidec and the South Korean economy are leading global economic indicators.

We live in interesting times, the next cycle is likely to different to those from the last 50 years.

Global synchronised recession with record debt levels and record low interest rates. What will happen with the next global recession: Deflation or coordinated attempts at global inflation as deflation with record debt levels is the worst of all worlds?

LikeLike

it will be v hard to generate inflation in such a climate – partly technically, but more so politically (including the evident reluctance of central banks to run risks to generate inflation in the last decade).

LikeLike

This today from the Economist: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2019/01/23/headlines-about-chinas-weak-growth-are-somewhat-misleading The main argument being that while the slowdown is likely real, it is from a larger base than previous – nominal GDP increasing by 8 trillion yuan, domestic consumption driving 3/4 of the growth. Still going to hurt in China though, is the conclusion.

LikeLike