There was a news story a few years ago in which some academics were reported as suggesting that pretty much everyone of West European descent alive today was descended from Charlemagne, first Holy Roman Emperor. That he had 18 children, legitimate and otherwise, only increased those probabilities. 35 generations back we each have about 34 billion notional ancestors and yet the total population of north-western Europe back then was only about 20 million.

I didn’t give the story much thought until last week. For the last few months my 12 year old daughter has been hard at work tracing family trees, with a bit of help from Dad. I was mostly interested in the last couple of hundred years, but she has been keen to trace every line possible as far back as we could go. We’ve put in some intense effort over the holidays and last week she stumbled on the path that took us all the way back to Charlemagne (and a couple of centuries before him). Just seeing that continuous path – one of the billions that made her her – on a couple of sheets of A3 gives a fresh vividness to those earlier centuries.

Of course, the other thing that even a little economic and social history does is to serve as a reminder of just how recent our material prosperity is. I downloaded a copy of the UK 1861 census form for one particular set of ancestors – just before they got on the (slow) boat for New Zealand. They were farm labourers in a small town in Yorkshire, living in a street where the other residents were also farm labourers and the like – and one is explicitly described as a pauper. The UK in 1861 had (on the Maddison database numbers) the best material living standards anywhere, rivalled only by Australia. But life was tough, hours were long, amenities were few, and (for example) infant mortality rates were shockingly high. According to a book a distant relative wrote recently, 26 people were to die on their trip to New Zealand – quite an “investment” in the prospect of better opportunities.

One of the children of that Yorkshire family, then just one year old, made the most of the opportunities 19th century New Zealand offered. He built businesses and served as mayor of Christchurch from 1912 to 1919 (and later as an MP). At the time, New Zealand is estimated to have offered among the very highest material standards of living anywhere in the world. But I wrote last year about what those “best material living standards” amounted to only a hundred years ago.

Imagine a country in which the average age at death was only about 45, 6 per cent of children died before their first birthday, and another 1.5 per cent before they turned five. Not many children are vaccinated.

Most kids get to primary school – in fact it is compulsory – but only a minority attend secondary school. By age 15 not much more than 15 per cent of young people are still at school. Only a handful do any post-secondary education (total university numbers are about 1 per cent of those in primary school). Houses are typically small – not much dedicated space for doing homework – even though families are bigger than we are used to. Perhaps one in ten households has a telephone and despite the street lights in the central cities most people don’t have electricity at home.

Tuberculosis is a significant risk (accounting for seven per cent of all deaths). Coal fires – the main means of heating and of fuel for cooking – mean that air quality in the cities is pretty dreadful, perhaps especially on still winter days. Deaths from bronchitis far exceed what we now see in advanced countries. There isn’t much traffic-related pollution though – few cars, so people mostly walk or take the tram. The biggest city is finally about to get a proper sewerage system, but most people outside the cities have nothing of the sort. And washing clothes is done largely by hand – imagine coping with those larger families.

Maternal mortality rates have fallen a lot but are still ten times those in 2018 in advanced countries. One in every 50 female deaths is from childbirth-related conditions – which leaves some kids without mothers almost from the start.

Welfare assistance against the vagaries of life is patchy. Most people don’t live long enough to be eligible for a mean-tested age pension. Orphans aren’t in a great position either, and there is nothing systematic for those who are seriously disabled. There is a semi-public hospital system, but most medical costs fall on individuals and families, and there just isn’t much that can be done about many conditions.

There are public holidays, and school holidays, but no annual leave entitlements. No doubt the comfortably-off take the occasional holiday away from home, but most don’t, because most can’t (afford it). Only recently has a rail route between the two largest cities been opened – but it takes 20 hours for cities only 400 miles apart.

I wouldn’t choose to live in that country. Would you?

And yet my grandparents did live there – they were all kids then. This was New Zealand 100 years or so ago, just prior to World War One. I took most of that data from the 1913 New Zealand Official Yearbook.

In constructing the family tree those infant mortality rates were brought home more vividly, when I found one great uncle and one great aunt both of whom died aged less than one in the years just prior to World War One, both in comfortable Christchurch families.

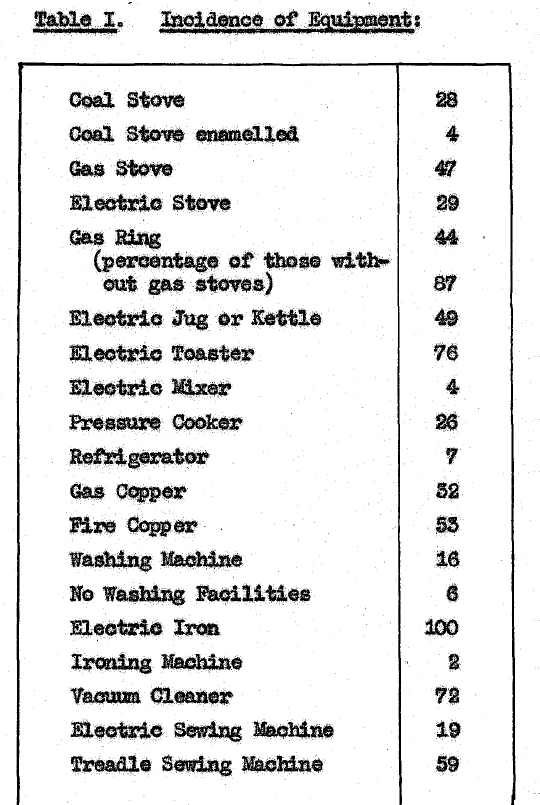

Over the holidays, I read an old masters thesis – written at Otago in 1950, and still occasionally cited – that somewhat updated the picture, at least as regards household management and facilities. According to the Maddison collection of data, New Zealand in 1950 still offered perhaps the third or fourth best material living standards anywhere in the world. This particular student had conducted what appeared to be a reasonably well-designed survey, and set of interviews, with women in a sample of households in central Dunedin, looking at what appliances each household had, which of a variety of services they used, and so on. The survey and interviews were conducted in early 1950. Here is one summary table.

You can see the spread of technology. 100 per cent of these households had an electric iron, and 72 per cent had a vacuum cleaner (presumably none would have in 1913). 76 per cent even had an electric toaster. But many were still cooking using a coal range, just under half had an electric jug or kettle, and only 7 per cent had a refrigerator – in a major city in one of the richest countries on earth, less than 70 years ago. There were, of course, few (probably no) domestic freezers, microwaves, dishwashers – or the myriad of more specialised appliances that now line the shelves of Briscoes. And, on the other hand, sewing machines were widespread.

The student recorded the occupational status of each household (typically, the employment of the husband) and analysed the incidence of these appliances across different occupational classes. The incidence of domestic technologies (those in the table above) in professional occupation households was, for example, about about twice that among labourers and pensioners (the differences being statistically significant).

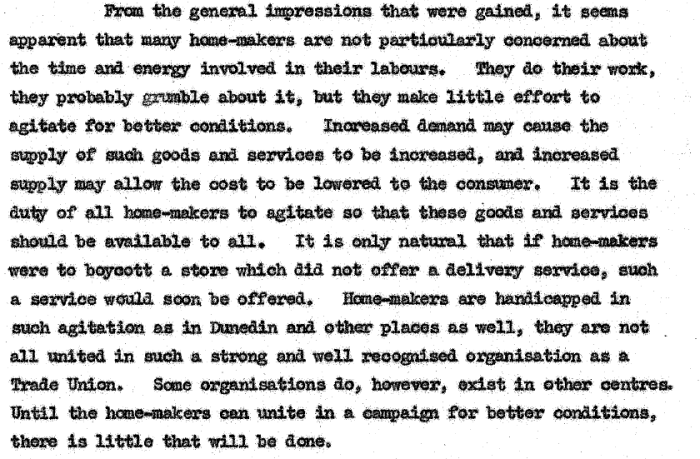

The second strand of the survey that underpinned the thesis was the use of various external services. When only 7 per cent of (these) households had a refrigerator – and presumably none a freezer – fresh food was a major issue.

Bread for example

(If you didn’t bake your own) it had to be collected every day it was baked. According to the survey most walked to the shop to buy it.

Around half of the respondents had their groceries delivered, and around 10 per cent shopped using their own car. The rest walked and carried the groceries home (typically from choice, since delivery was generally available). Meat couldn’t be stored with long without a fridge, and the survey found that few butchers offered to deliver, so a walk to the butcher was pretty much a daily requirement. Many of the respondents didn’t have a telephone, so even if delivery had been available, they’d still have to have walked to the butcher to place the order.

What of fruit and vegetables?

The thesis goes on to look at the use of commercial laundry services, house-cleaning and window-cleaning services (including a slightly arch comment about the one respondent who claimed never to clean their windows), and the employment of people to assist in household chores or child-minding.

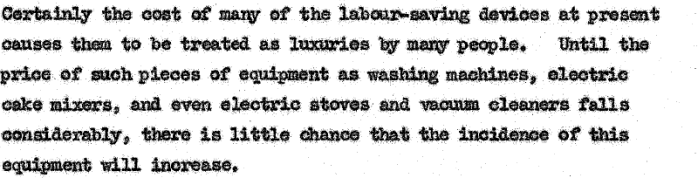

Perhaps like all writing, that 1950 thesis is also something of a period piece. There are asides about the price controls and butter-rationing still in place in post-war New Zealand, and a near unwavering sense that household management is a woman’s work. And if there is a recognition of the importance of price – this was, after all, a thesis partly done under the Economics Department

there were also some curious asides

Best national accounts estimates suggest that average material living standards in New Zealand in 1950 were not much more than a third of those today (and over that period New Zealand has had among the slowest rates of productivity growth of any country). The data captured in that thesis help illustrate some of the concrete differences.

That thesis was my mother’s. She is the great-granddaughter of that 1861 Yorkshire farm labourer, and the great-niece of that former mayor and MP – she was told to blame him when she couldn’t start school at five (Depression-era economies by the government of which he was an MP). She was the first person on either side of my daughter’s family tree to graduate from university (at least in modern times), at a time when only about 5 per cent of young people went to university (and only about 1 per cent of women). In one of the richest countries in the world.

It is her 91st birthday today. There have been staggering material changes over the span of her life, let alone that of her grandparents and their generation. Echoing Robert Gordon perhaps, I’m less convinced that if I live to 91, there will have been anything like that scale of improvement over my life. I’m just about to walk to the butcher and supermarket. Then again, in 1962 one couldn’t trace back generations of ancestors from the comfort of one’s own computer screen.