I wasn’t planning to write today about the Reserve Bank’s proposed new bank capital requirements, announced yesterday. I’ll save a substantive treatment of their consultative document until (after I’ve read it and in) the New Year. But I found myself quoted in an article on the proposals in today’s Dominion-Post, in a way that doesn’t really reflect my views. Perhaps that is what happens when a journalist rings while you are out Christmas shopping and didn’t even know the document had been released. But I repeatedly pointed out to him that, despite some scepticism upfront, I’d have to look at documents in full and (for example) critically review any cost-benefit analysis the Bank was providing before reaching a firm view.

The gist of the proposal was captured in this quote from Deputy Governor Geoff Bascand

“We are proposing to almost double the required amount of high quality capital that banks will have to hold,” Bascand said.

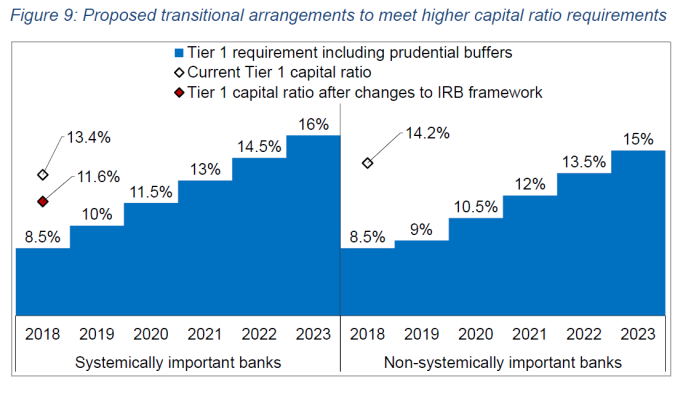

Or in this chart I found on a quick skim through the document.

These are very big changes the Governor is proposing. As I understand it, and as reflected in my comments in the article, they would leave capital requirements (capital as a share of risk-weighted assets) in New Zealand higher than almost anywhere else in the advanced world.

These were the other comments I was reported as making

The magnitude of the new capital required by banks surprised former Reserve Bank head of financial markets, Michael Reddell, who now blogs on the central bank.

A policy move of this scale would have an impact on the value of New Zealand banks, though ASB, BNZ, Westpac and ANZ are all owned by Australian companies listed on the ASX sharemarket.

“If these were domestically listed companies, you would see the impact immediately,” Reddell said.

That would be through a fall in the price of their shares.

Many KiwiSaver funds own shares in the Australian banks.

I think the journalist got a bit the wrong end of the stick re the first comments – perhaps what happens discussing such things, sight unseen, in a carpark. In many respects the magnitude of the increase isn’t that surprising given that the Governor had already indicated – a week or so before – his desire to have banks able to resist sufficiently large shocks that, on specific assumptions, systemic crises would occur no more than once in 200 years. That is much more demanding than what previous capital requirements have been based on – the same ones the Reserve Bank produced a cost-benefit analysis in support of only five or so years ago, and which have had them ever since declaring at every FSR how robust the New Zealand banking system is.

As for the second half of the comments, they were a hypothetical in response to the journalist’s question about whether higher bank capital requirements would be felt in wealth losses by (for example) people with Kiwisaver accounts who might hold bank shares. He was uneasy about the line the Bank used that the increased capital requirements were equivalent to 70 per cent of estimated/forecast bank profits over the five year transitional period (of itself, this isn’t an additional cost or loss of wealth). My point was that if the New Zealand banks (subsidiaries of the Australian banks or Kiwibank) were listed companies, such an effect would be visible directly, because (rightly or wrongly) markets tend to treat higher equity capital requirements as an additional cost on the business, and thus we could have expected the share price of the New Zealand companies to fall, at least initially. As it is, I’d have thought it would be near-impossible to see any material impact on the share price of the parents (or thus on the value of any shares held in Kiwisaver accounts).

My bottom-line view remains the one I expressed here a couple of weeks ago

Time will tell how persuasive their case is, but given the robustness of the banking system in the face of previous demanding stress tests, the marginal benefits (in terms of crisis probability reduction) for an additional dollar of required capital must now be pretty small.

And, thus, I’m looking forward to critically reviewing their analysis, including in the light of that previous cost-benefit analysis. Is it really worth compelling banks to hold much more capital than the market seems to require (even from institutions small enough no one thinks a government will bail them out)?

In thinking through this issue, there are some other relevant considerations to bear in mind. The first is to reflect on just how unsatisfactory it is that decisions of this magnitude are left to a single unelected individual who, in this particular case, does not even have any particular specialist expertise in the subject. And his most senior manager responsible for financial stability only took up his job a year ago, having previously had no professional background in banking, financial stability or financial regulation. The legislation is crying out for an overhaul – big policy decisions like these really should be made by those we can hold to account (elected politicians). And note that banks have no substantive appeal rights in these matters, even though the Governor is, in effect, prosecutor, judge and jury, and (in effect) accountable to no one much.

The other is to note that there is likely to be very considerable pushback from Australia on these proposals – both the parent banks of the subsidiaries operating here and, quite probably, from the Australian regulator (APRA) itself. The proposed new capital requirements here are far higher than those required in Australia (and for the banking groups as a whole). APRA has adopted a standard that Australian banks should be capitalised so that the system is “unquestionably strong”, but their Tier 1 capital requirement is apparently “only” 10.5 per cent. Of course, subsidiaries operating in New Zealand are New Zealand registered and regulated banks, and our authorities should be expected to regulate primarily in the interests of New Zealand. We won’t look after Australia, and they are unlikely to look after us, in a crisis (and coping with crises are really what bank capital is about). But you have to wonder why we should be inclined to place such confidence in our Reserve Bank’s analysis, relative to that of APRA – an organisation with (especially now) much greater institutional depth and expertise. Given the legislated trans-Tasman banking commitments, and the common interests of the two sets of authorities in the health of the banking groups, one can’t help thinking that it would have been more reassuring to have seen the two regulators (and the two governments for that matter – limiting fiscal risks in the event of bank failure) reach a rather more in-common view on the appropriate capitalisation of banks in Australasia.

But perhaps the Governor really is leading the way, supported by compelling analysis. More on that (superficially unlikely) possibility in the New Year. In the meantime, for anyone interested, there is a non-technical summary of their proposal (although not of any supporting analysis) here.

There are mainly 2 ways in a public company to raise capital. You can either initiate a rights issue, ie a demand of cash from existing shareholders or you issue new shares to new shareholders. Both of which usually requires issuing new shares. Therefore share price fall, not because of any view of higher additional costs to the business but because of the dilution of earnings per issued share due to the higher number of shares in the market.

LikeLike

The higher cost to the business dies not come from increased capital but from the higher cash reserves that need to be held earning a lower return than the returns from lending the cash reserve out. The higher cost is more to do with a lower return on capital employed rather than capital per say.

LikeLike

I don’t believe the dilution is a function of the capital sitting in a higher cash balance. The extra capital held just changes how the assets are financed. More capital means less liabilities. Cash earnings probably increases but ROE declines because the percentage increase in capital exceeds the benefit of the interest expense saved.

LikeLike

More shares issued in the market from a capital raising has to dilute earnings per share and a result a drop in market value. Simple maths.

LikeLike

The intent of the capital raising is to increase the prudential reserve which means a bank has to sit on more cash reserves. It does not equate to less liabilities. If you use the cash to pay down liabilities you won’t have a prudential reserve.

Cr Capital

Dr Prudential Reserve ie cash in bank

LikeLike

Perhaps we will have to agree to disagree but my understanding is that the amount of cash held by a bank is driven by liquidity requirements not capital requirements.

One of the functions of capital is to absorb loss which is why the RBNZ wants their banks to use more capital and less debt. Bank balance sheets evolve every day. So yes the point in time impact of raising more equity is a cash inflow but cash flows in and out every day so that cash does not necessarily stay on the balance sheet unless the bank decides to hold more cash. The requirement to hold more capital does not in itself require that the bank hold more cash (or other liquid assets).

LikeLike

The simple point is a bank should understand its risks and invest on understanding them to a greater degree. The FRTB regime being implemented in the coming years in all G20 countries will in fact go the opposite way to the RBNZ and require banks to invest heavily in their internal risk systems and having to rely on the standard model when their risk systems don’t meet strict performance criteria (and yes, there will be a floor between the internal models and standard as well… but not at 90%).

The RBNZ don’t have the skillset to challenge the banks on their current internal models and how they are implemented. That is the issue.

There is no further proof needed of the RBNZ’s ineptitude than by them focussing on common equity… yup.. we saw how confused they got with Kiwibank’s capital issuance…. they have simply put loss absorbing issuance in the too hard basket. Sophisticated investors understand where they are in the capital structure.. pity there is no element of sophistication at the RBNZ.

Comment on Interest.co.nz by Andyb a banker.

LikeLike

The company can also reduce dividends and grow equity via increased retained earnings. The NZ banks are mostly subsidiaries so it is easier for them to do this than it would be if the change in dividend directly impacted external shareholders as it does for publicly listed companies. Companies obviously don’t like doing this but it is an option.

LikeLike

Yes you can retain more dividends but banks dividend payment policy is not at discussion or targetted by the RBNZ. That is why a record profitable bank this year is not necessarily a stable bank next year as dividend payments strip out retained earnings from the banks equity.

LikeLike

The RBNZ specifically noted that the capital required to achieve their target could be achieved by retaining earnings

Para 115 “On the other hand, there will also be practical differences in the ability and responsiveness of small and large banks to our proposed capital requirements. One can look at the time it would take banks to achieve 16 percent Tier 1 capital, assuming all banks grow at a similar rate (here we assume all banks’ credit exposures grow at 6 percent, a similar rate to the growth in credit across the system in recent years). We estimate that the large four banks would be able to achieve the 16 percent target over a period of approximately 5 years through retained earnings alone, taking into account proposed changes to the IRB framework that affect their RWA calculation. In contrast, we estimate that the smaller banks, as a group, would take longer, something in excess of 7 or 8 years. “

LikeLike

The section of their paper “Operational aspects of prudential capital buffer” talks a lot about dividend policy. Para 115 also notes that the extra capital required could be raised by retaining all earnings over a number of years. Banks may not like suspending dividend payments but this happened to many banks in the UK and USA as they increased the capital they held.

LikeLike

Hi Mike

I see the AFR reporting today that APRA say they were “consulted” about the RBNZ release last Friday which was the document’s release date. Is there any protocol for consultation between APRA and RBNZ on these types of regulatory issues? It seems surprising to me that the RBNZ could propose something so radical without a genuine prior discussion with the regulator of the banks who dominate the NZ financial system.

LikeLike

Thanks for that reference. It is consistent with what I saw in the Australian yesterday which noted that APRA would be engaging with the RBNZ (future tense, no suggestion of any prior consultation).

In terms of legislative provisions etc there is this provision added to thr RB Act in about 2006

http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1989/0157/latest/DLM200337.html

and the MOU between the Bank and APRA signed in 2012

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/-/media/ReserveBank/Files/regulation-and-supervision/banks/relationships/4796879.pdf?la=en

The legislative provision is mostly about actions in a crisis, and both sides agreeing to do all they can not to queer the pitch for the other.

The MOU is more about ongoing supervision but on policy development says only this

“Regulatory Policy Development

25. The Authorities expect to respond to requests for information on their respective national regulatory systems and inform each other about major changes, including those that have a significant bearing on the activities of Cross-border Establishments.”

but even that is pretty weak. I agree that it seems remarkable, and quite inappropriate, if there hasn’t been material advance consultation with APRA, including testing the argumentation/analysis/evidence with a regulator with similar ex ante interests and a much deeper bench of expertise.

There may also be questions about how much advance consultation/notification there was with our own government. Such consultation isn’t required by law, but is strongly advised and is pretty much an expectation from most ministers.

LikeLike