The Reserve Bank’s Annual Report was published yesterday. I’m not overly interested in the Bank’s own Annual Report, although a couple of things (one an omission) caught my eye.

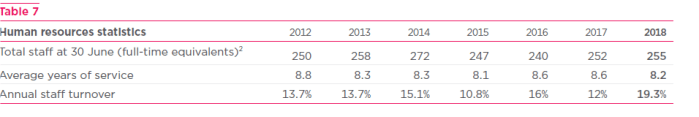

The first was the sharp increase in staff turnover last year

Staff turnover of almost 20 per cent is very high. The Bank explains it this way

Staff turnover increased during the year to an unusually high level for the Bank, in part due to an increase in the number of retirements and staff going on external secondments for development.

But it (even the “in part” bit) isn’t a very compelling explanation – although I suppose both the Governor and Deputy Governor retired – and the Bank hasn’t had any material changes in responsibilities, reduced budgets etc in the last year. It would be interesting to know what the results of their most recent staff engagement survey looked like – probably not that good when turnover is that high.

And it was a touch surprising that the Bank’s (self-adopted) Maori name doesn’t appear in the text at all, and even more surprising that the Governor’s new enthusiasm for talking of the Bank as some mythological pagan tree god doesn’t appear at all. The report was signed off only three weeks ago, and we know this nonsense was well underway by then. Perhaps the Governor didn’t think it would play well with Parliament – although I’d have thought it might be one of the few places where it might be well-received.

But my main interest was in the Annual Report of the Bank’s Board – a separate statutory requirement. I’ve written about these reports each year (2015, 2016, and 2017), mostly repeating the points that:

(a) the Board isn’t like a real board of a business, a Crown entity, or even a charity or sports club having few/no decisionmaking responsibilities, instead

(b) the main role of the “Board” is to monitor and hold to account (on behalf of the Minister and the public) the Governor, and yet

(c) the Board has consistently acted, and communicated, as if their primary role was to have the back of the Governor, serving his interests not those of the public.

And so no discouraging or critical word was ever heard from the Board, even in (say) egregious instances of the Governor attacking individuals. From reading Board annual reports over the years you’d have to suppose that the Bank was perfect – the sort of entity unknown to humankind – or that the Board was supine, and useless to taxpayers.

Consistent with all this, the Board’s Annual Report has been buried inside the Bank’s report – you can’t even find it separately on the Bank’s website. There is no press release from the chair about the Board’s report, and no mention of the Board’s annual report in the Governor’s own press release. It still has the feel of a tame appendage of the Bank, working mostly in the Governor’s interests (even if this year, for some reason, the Board’s report this year features first in the combined document itself).

But there has been some improvement over recent years. A few years ago, the Board’s report was a mere two pages, and now it is five pages (with some other relevant descriptive material – eg around conflicts of interest and remuneration of directors – included in the Bank’s report). There is also still a (relatively minor perhaps) factual error. But there are some signs in this year’s report suggesting that just occasionally the Board thinks for itself. Perhaps this isn’t unrelated to the fact that the second stage of the review of the Reserve Bank Act is looking at, among other things, the role of the Board and whether it adds any real value in its current form.

What in this year’s report makes me just slightly encouraged?

It certainly isn’t the treatment of monetary policy. Reading the report you wouldn’t know that core inflation had been below the midpoint of the inflation target for eight years, even after the midpoint was made the explicit focus of monetary policy (by agreement between the Governor and the Minister) in 2012. Instead, there is simply heartwarming praise of the policy processes, and if there are any issues at all about inflation they are, apparently, all the fault of the “global environment”. Then again, none of the Board has any particular expertise in monetary policy.

But there were several positives.

First, while backing the inquiry into banking conduct and culture in New Zealand being undertaken by the FMA and the Reserve Bank, they explicitly note that

“conduct concerns are formally within the remit of the FMA”

which is a point I’ve been making for months, but which the Governor has never been willing to acknowledge, preferring to be the most visible face of an issue that really isn’t his responsibility. It is a small acknowledgement, but they didn’t need to say it, and yet they chose to do so. That deserves credit.

Second, the Board’s report explicitly refers to the damning survey results on the Reserve Bank published earlier this year in the New Zealand Initiative’s report on regulatory governance. This was the report which summarised the results thus

In the ratings, the RBNZ’s overall performance across the 23 KPIs was poor. On average, just 28.6% of respondents ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that the RBNZ met the KPIs and 36% ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’. These figures compare very unfavourably with the FMA’s average scores of 60.8% and 10.3%, respectively. They also compare unfavourably (though less so) with the Commerce Commission’s averages of 39.9% and 25.8%, respectively.

The Board writes

The Bank’s own relationships with regulated entities came under scrutiny with the publication of an independent review of regulatory governance in New Zealand. The Board met with the Chairs of the Boards of the four large trading banks as a means of gauging whether the opinions expressed in the review are widely held. Both the Board and the Governors are looking for continuous improvement in how the Bank interfaces with the regulated entities, specifically how it assesses the soundness and efficiency of its own regulatory actions (including the risks of unintended and inefficient consequences); how it assesses any tradeoffs between these two objectives; and how it reports on efficiency as well as soundness.

Pretty tame stuff, but better than nothing, and at least a recognition that there has been a problem. The Governor’s own statement, by contrast, explicitly mentions the IMF FSAP and questions about the handling of CBL, but doesn’t mention at all this heavy criticism from well-informed locals, and the body of the report appears to brush off the NZI report results as largely resulting from one particular disputed policy (which frankly seems unlikely – well-regarded and trusted institutions don’t score that badly when there is simply one specific thing that happens to upset people).

On CBL, however, the Board seem mostly in the mode of covering for management.

Given the public comment that was associated with the Bank securing interim liquidation of CBL Insurance Limited, the Board requested information on the legal advice obtained and the reasons why the Bank’s investigation was not disclosed prior to court action being sought. The obligation to make disclosures to the share market rests with company directors, and a statutory requirement for confidentiality applied to the Bank’s investigation.

It is good that the Board asked the questions, but the answers don’t seem very satisfactory. It was, after all, as I understand it, the Reserve Bank that compelled CBL not to tell shareholders (or, indirectly, creditors) what was going on.

My third small positive related to how the Board tells the story of what it does.

In the past, the Board has talked about cocktail functions it holds (for local elites) around various Board meetings this way

With most Board meetings…the Board hosts a larger evening function to engage with representatives of many local businesses and organisations, and to enhance our understanding of local economic developments and issues……. This outreach is a longstanding practice of the Board to ensure visibility of its role among the wider community, and to facilitate directors’ understanding of local economic developments, and the wider public’s understanding of the Bank’s policies.

But here they are this year

The Board met with business representatives and other important stakeholders over lunch at many of its meetings, and also hosted functions for local stakeholders following its regular meetings in Auckland and Wellington. These functions provide an opportunity for stakeholders to discuss issues with the Board and Governors following a presentation by Governors. The Board pays particular attention to any feedback on the messaging, transparency and accountability of the Bank, and is looking to the new Governor to ensure that there are improvements in some key stakeholder relationships in the next year.

If they still seem to tie themselves too closely to the Governor, there is a clear shift of emphasis – at least in how they sell themselves in public – recognising a little more that their job is not to promote the Bank’s policies, but to ensure that the Governor is doing his job. The explicit final sentence is the sort of thing one should expect, from time to time, from the Board, but which has been notably absent over the previous fifteen years of reports. It is a welcome step forward and thus – credit where it is due – I’d give them a (bare) pass mark this year.

Under the amending bill currently before Parliament the Board’s powers are to be beefed-up further, as regards the new Monetary Policy Committee. I regard that as quite inappropriate: the Board members have no relevant expertise, and no legitimacy in their role determining who will set macroeconomic policy for New Zealand. But the bigger questions are still to be addressed in the second stage review of the Reserve Bank Act, and so no doubt the Board needs to be seen on its best behaviour, at least looking as if it is adding some small amount of value.

But the institutional incentives, and resourcing (lack of it) mean that any improvements are unlikely to be durable or amount to much, even if individual board members were well-intentioned.

Thus, welcome as the small improvements in this year’s report are, I remain of the view that the Board in its current form should be dis-established, If, as I would favour, the Bank is eventually split in two, there should be proper decisionmaking boards for each of the monetary policy and financial regulatory agencies. That is how most Crown entities – large and small, visible and not – are governed. Scrutiny and review mostly always will – and probably should be – done by those outside the Bank: the Treasury, MPs, financial markets participants, academics, and independent commentators, supported by pro-active practices and statutory provisions around the release of relevant documents . In support of those efforts, I will continue to argue that the proposed independent fiscal monitoring agency should be broadened to include responsibility for providing independent monitoring and commentary on monetary policy and the Bank’s financial stability responsibilities. Board members, sitting with management every month and with the Governor as a Board member, resourced by the Bank itself, simply can’t hope to be able to provide the level of detached scrutiny the public deserves of such a powerful public agency.