On Monday, just across the road from Parliament, Victoria University’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies hosted a lunchtime lecture from Professor Anne-Marie Brady. The lecture was built around her Magic Weapons paper on the extent of Chinese government/Party influence activities in New Zealand (and elsewhere), and her shorter policy brief with some specific proposals for the new government on how to deal with the issue (I wrote about that latter piece recently here). (Radio New Zealand also had a good interview with Brady this morning, prompted by the new legislation announced yesterday by the Australian government, as part of its efforts to deal with this official Chinese interference.)

New Zealanders owe Professor Brady a considerable debt of gratitude for, first, writing her detailed paper, and secondly for deciding to put it in the public domain (it was done as part of an international project on Chinese influence-seeking activities globally, and the papers by other scholars have not yet been made public). Her paper has found a receptive audience internationally (and she mentioned that Francis Fukayama has underway work for a similar paper on Chinese influence-seeking in the US).

Listening to her, one gets the sense that she isn’t that comfortable in the public spotlight. Many academics aren’t. In her lecture the other day she felt the need to include a photo of her Chinese husband and her three half-Chinese children – no doubt a push back against the sort of despicable pre-election attempt to discredit her and her research tried by the then Attorney-General. It can be a lonely position for an academic when her expert and well-documented research runs head-on into a wall of political indifference (or worse), vested interests, and a media which seems not quite sure whether or not this is a “proper” issue even to be talking about. It is not as if (I’m aware that ) anyone has seriously sought to question the factual basis of her paper, or has demonstrated major flaws in her analysis and reasoning. It seems as if there is just a desperate desire that she, and the issue, would go away. Absent that, the political and business elites simply want to pretend it doesn’t exist. I hope she doesn’t just retreat to her study.

Her Victoria lecture the other day covered pretty familiar ground (although many of the attendees indicated that they hadn’t read either of her papers so much will have been new for them). There was:

- the active efforts (largely successful) of the Communist Party to get effective control of almost all Chinese language media in New Zealand (similar story in Australia) – and thus the story of the issues she is raising goes unreported in that media,

- the efforts of suborn former senior politicians, with roles that align their personal economic interests with those of the Chinese authorites,

- concerns about political donations, especially from individuals/entities with close ties to the CCP, and the associated close ties between political party leaders and China,

- Chinese government interests in influencing New Zealand, both to stay quiet on issues of concern to China, and to detach New Zealand from its historical defence and intelligence relationships,

- China’s interests in Antartica,

- Confucius Institutes, funded and controlled by China, as part of New Zealand universities, complete with restrictions on what can be talked about,

- efforts to promote ethnic Chinese New Zealand citizens, with those ties to the Embassy/CCP, into electoral politics – in New Zealand’s case, both Jian Yang and Raymond Huo.

Huo is now chair of Parliament’s Justice Committee – the same Huo who, as she pointed out, is responsible for Labour campaigning for the Chinese vote under a Xi Jinping slogan, and who – Professor Brady reports – was present at a meeting in Auckland earlier this year in which Communist Party propaganda chiefs (“propaganda” is apparently a literal translation of the role/office) met with local Chinese language media to offer “guidance” on how issues of interest to China should be reported. A serving member of New Zealand’s Parliament…….

Brady noted that the Communist Party’s United Front work has always been an integral element in how the Party works, but that the efforts are now being undertaken with an intensity and importance that is greater than at any time since 1949, when the CCP took power. It is a China that has thrown off Deng Xiaoping’s injunction (post Tiananmen) that China should mask its growing power and bide its time.

When it came to the New Zealand government, in some respects I thought Professor Brady pulled her punches (although she was happy to note that she couldn’t understand how it was that National Party MP Jian Yang – self-confessed Communist Party member, former member of the Chinese intelligence services, and someone who has acknowledged misrepresenting his past on residency/citizenship application papers – is still in Parliament). I’m not sure how much of that is tactical – giving the new government a chance, hoping to be heard by talking constructively. I fear that any such hope is misplaced.

In just the last week we’ve had a couple of episodes that confirm that the new government is quite as craven – indifferent, obsequious – as its predecessor.

A month or two ago, at the time of the 19th Communist Party Congress, it came to light through the Chinese media that the presidents of both the National and Labour parties had been sending warm greetings and congratulations. This last weekend, the Labour Party went one step worse.

The Chinese Communist Party held a congress in Beijing for representatives of such political parties from around the world (300 from 120 countries) as it could gather to its embrace. Most of them were from developing countries. Nigel Haworth, the President of the New Zealand Labour Party, attended. Here is how one Chinese media outlet reported the event.

The CPC in Dialogue with World Political Parties High Level Meeting was the first major multilateral diplomacy event hosted by China after the recently concluded 19th CPC National Congress.

It was also the first time the CPC held a high-level meeting with such a wide range of political parties from around the world…..

During the closing ceremony, Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi stressed that the meeting was a complete success with a broad consensus reached. He also said CPC leaders elaborated on the new guiding theory introduced by the 19th CPC National Congress.

“The innovative theoretical and practical outcomes of the 19th CPC National Congress not only have milestone significance for the development of China, but also provide good examples for the development of other countries, especially developing countries,” Yang said.

The Beijing Initiative issued after the meeting states that over the past five years, China has achieved historic transformations and the country is making new and greater contributions to the world.

It also highlighted that lasting peace, universal security, and common prosperity have increasingly become the aspiration of people worldwide, and it’s the unshakable responsibility and mission of political parties to steer the world in this direction.

“The most important thing between the 18th and 19th CPC party congress was the belt and road initiative,” according to the Russian Communist Party’s Dmitry Novikov. “And the most important thing about the initiative is the economic cooperation among various countries. Such cooperation leads to the promotion of relations in culture and politics.”

And the President of the New Zealand Labour Party was party to all of this. In fact, not just a party to it, but someone who was willing to come out openly in praise of Xi Jinping.

Here he is, talking of Xi Jinping’s opening speech (here and here)

“I think it is a very good speech. I think it is a very challenging speech. I think he is taking a very brave step, trying to lead the world and to think about the global challenges in a cooperative manner. Historically we have wars and we have crisis, but he is posing a possibility of a different way of moving forward, a way based on collaboration and cooperation. Making cooperation work is difficult, but he think that’s a better way for mankind. I think we all share that view.”

It is shameful. Probably not even Peter Goodfellow would have gone quite that far – if only because there might have been some (understandable) rebellion in the ranks if he had gone that public.

This is the same Chinese Communist Party (and associated state) that

- flouts international law, including with its aggressive expansionism in the South China Sea,

- denies any political rights to its own people,

- that is directly responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people (and which only just pulled back from its forced abortions practices),

- lets dissidents die in prison,

- has no concept of the rule of law,

- persecutes religious believers (Christian, Muslim, Falun Gong or whatever),

- actively interferes in the domestic politics of other countries in all manner of different ways,

- and so on.

In her lecture the other day, Professor Brady mentioned Haworth’s comments, but this was one of the places she pulled her punches. She asked, rhetorically, if we could imagine a New Zealand political party president attending a Republican Party convention and making such public remarks. Or even a Russian political event. At one level it is a fair point – Haworth’s participation in this CCP event, and his positive comments, have gone totally unremarked in the New Zealand media (or from Opposition parties), in a way that would be simply inconceivable in those other cases. But at another, it falls into the trap beloved of China-sympathisers and people on the left (one such academic at her lecture attempted this), of drawing a moral equivalence between, say, the United States and the UK on the one hand, and Communist China on the other. A much better comparison would be to ask if we could imagine a major New Zealand political party President attending Nazi Party congresses pre-war or Soviet Communist party congresses? And whether, even if it had happened, we would look back now with equanimity at associating so strongly with such an evil. Such is the CCP. The fact that certain New Zealand firms make a lot of money trading with them – or that our political parties appear to raise large donations – doesn’t change that character.

Former National Party Prime Minister, Jenny Shipley, was apparently also at the meeting, speaking warmly of China’s One Belt One Road initiative (all about geopolitical influence).

Yesterday, we had yet more proof of how far gone the New Zealand authorities (and the new New Zealand government are). As I’d noted a couple of weeks ago, Victoria University (specifically its China-funded and controlled Confucius Institute) and the New Zealand Institute for International Affairs put on a half day symposium (celebration?) of 45 years of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China PRC). Not a word of scepticism or criticism was to be expected from the programme – there wasn’t for example an opportunity for Professor Brady to present her work, and alternative perspectives on it to be heard.

Quite late in the piece, reportedly, the new Minister of Foreign Affairs agreed to be a keynote speaker at this forum, his first major speech as Minister. Winston Peters had, in Opposition, occasionally been heard to express some unease about the activities of the PRC in New Zealand, including the questions around National Party MP Jian Yang (recall that even Charles Finny, former senior diplomat, noted that he is always very careful about what he says in front on Yang and Raymond Huo, given their closeness to the PRC Embassy). In office, the Rt Hon Winston Peters not just tows the MFAT line, repeating the same obsequious words as former National Party ministers, he takes it up another step.

There was the published text, which was bad enough. In entire speech he could only manage this, that might be pointed to for a modicum of self-respect.

New Zealand supports a stable, rules-based order in the Asia-Pacific region in which free trade and connectivity can thrive. We urge parties to resolve disputes in accordance with international law, on the basis of diplomacy and dialogue.

New Zealand and China do not always see eye to eye on every issue; we are different countries and New Zealanders are proudly independent. However, China and New Zealand have a close, constructive and increasingly mature relationship. Where we do have different perspectives, we raise these with each other in ways that are cordial, constructive and clear.

“New Zealanders” might be proudly independent, but it isn’t clear that our governments are. At a New Zealand event – so it wasn’t even a matter of talking politely in China itself – our Foreign Minister can’t bring himself to name any specific concerns or risks (despite rising international unease, and the material documented by Professor Brady). And if he ever has concerns he’ll raise them in “cordial” way………”cordial” and direct interference by a foreign power in New Zealand, undermining the freedoms of hundreds of thousands of our own people (ethnic Chinese) doesn’t strike me as the sort of words that naturally belong together. At least in a country whose government retains any self-respect.

But then it got worse, at least according to the Stuff report of how Peters departed from his written text.

“We should also remember this when we are making judgements about China – about freedom and their laws: that when you have hundreds of millions of people to be re-employed and relocated with the change of your economic structure, you have some massive, huge problems.

“Sometimes the West and commentators in the West should have a little more regard to that and the economic outcome for those people, rather than constantly harping on about the romance of ‘freedom’, or as famous singer Janis Joplin once sang in her song: ‘freedom is just another word for nothing else to lose’.

“In some ways the Chinese have a lot to teach us about uplifting everyone’s economic futures in their plans.”

It is so remarkably reminiscent of the Western fellow travellers of the Soviet Union in decades past – tens of millions might die, but not to worry, a new Jerusalem is on the way to being built. Basic rights and freedoms might be trampled on, or simply not exist at all, but not to worry….what is freedom after all?

Personally, I don’t think the biggest issue in the China/New Zealand official relationship should be how the Chinese party/state treats its own people – abominable as that is. The issues people like Professor Brady are raising are about the direct, systematic, in-depth, interference by another country – a hostile power, run by a regime with mostly alien values – in the domestic affairs of other countries. Our own most of all. International expansionism and defiance of the rule of international law might matter too. And none of that has any connection whatever to improvements in material living standards in China.

And what to make of the nonsense claim that “the Chinese have a lot to teach us about uplifting everyone’s economic future in their plans”. That is about as ignorant as it is offensive.

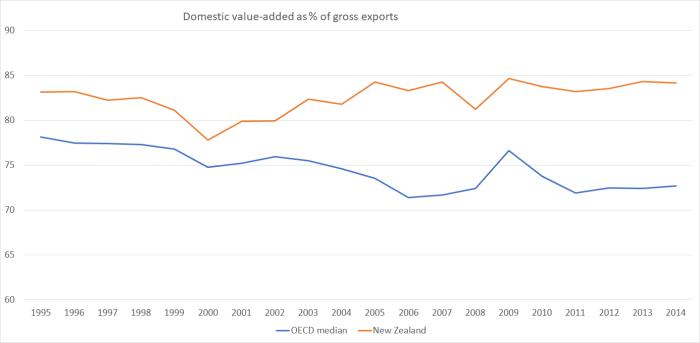

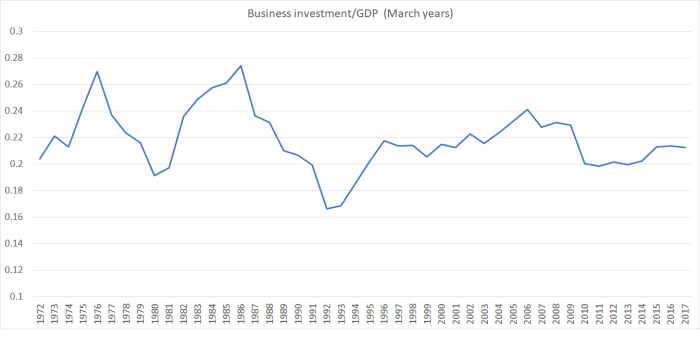

I’ve shown this chart before

Here is a chart showing GDP per capita for China, and a range of now-advanced Asian countries/economies. I’ve shown each country’s GDP per capita as a percentage of that for the United States for each of 1913, 1950, and 2014, using the Maddison database for the 1913 observation and the Conference Board (which built on Maddison’s work) for the more recent observations. Data are a bit patchy in those earlier decades, but 1913 was before China descended into civil and external wars (from the late 1920s), and 1950 was the year after the Communist Party took control of the mainland.

What stands out is just how badly communist-ruled China has done economically, and especially relative to the three other ethnic-Chinese countries/territories. Substantial re-convergence has happened in all the other countries on the chart, but that in China has been excruciatingly slow. A few buoyant decades (the aftermath of which we have still to see) struggle to make up for the earlier decades of even worse Communist mis-rule.

Or how about this one, using Conference Board data for real GDP per person employed (they don’t have real GDP per hour worked for China, but estimates are very low)?

Even on official Chinese data, the record is pretty poor: China barely matches Sri Lanka which was torn apart by decades of civil war, and doesn’t even begin to match the performance of the better east Asian economies (none of which has anything like the waste, the massive distortions, of China). Surely China is best seen as a (potential) wealth-destruction story? Taiwan’s numbers might be a reasonable benchmark for what could have been. Taiwan threatens no one.

Just to cap an egregious speech, the Opposition foreign affairs spokesman indicated that he didn’t disagree with what Winston Peters had had to say (well, after his government’s track record of cravenness, he would, wouldn’t he).

I came home from Anne-Marie Brady’s lecture the other day and pulled off the bookshelf my copy of The Appeasers, written in the 1960s by Martin Gilbert and Richard Gott, a heavily-documented account of British appeasement of Germany from 1933 onwards. As I started reading, lots seemed to ring true to today.

Two situations are never fully alike. For a start, New Zealand isn’t a “great power” and China is (as Germany was becoming again). And Germany had little real interest in interfering in domestic British politics – and there was no large German diaspora in the UK to attempt to corral and control. But there is a lot of the same willed blindness to the evil that the regime represented. In the 1930s, it wasn’t the bureaucrats who were the problem – from the very first, British Ambassadors in Berlin recognised and reported on the nature of the regime, its domestic abuses and its external threats. There were various forces at work it seemed – a fear of Communism (and thus Nazism as perhaps some sort of bulwark against something even worse), unease and even guilt over some of the Treaty of Versailles provisions, the fear of new conflict (only 15 years after the last war), and often some sort of admiration for the order the new German government was bringing to things (and some philo-Germanism among many of the British upper classes). As Gilbert and Gott summarise it

“Like alcohol, pro-Germanism dulled the senses of those who over-indulged, and many English diplomats, politicians and men of influence insisted upon interpreting German developments in such a way as to suggest patterns of cooperation that did not exist.”

Britain and France could (and should) have stopped Germany earlier. New Zealand can’t stop China, of course, but we can assert ourselves, and reassert some self-respect, for our system, our freedoms, and for the interests of like-minded countries. We can call out, firmly (not cordially) Chinese influence-seeking etc where we see it – as the Australian government has been much more willing to do. We can cease to pander to such an obnoxious regime that not only abuses its own people (including failing to deliver economically) but represents a threat to its neighbours, and which persists in seeking to interfere directly in other countries, whether in its neighbourhood or not, whether with large ethnic Chinese minorities (as NZ, Australia, and Canada) or not. Our politicians shame us by their deference to such an evil power – and frankly, one that has little real ability to harm us (as distinct from harming a few vested interests).

In her lecture the other day, and in her policy brief, Anne-Marie Brady called for our political leaders to insist that none of their MPs will have anything further to do with entities involved in the PRC United Front efforts. That would certainly be a start – though the Jian Yang stain on our democracy really needs to be removed altogether – but it is probably a rather small part of the issue: we need political leaders who will recognise – and openly acknowledge – the nature of the regime, and stop fooling themselves (and attempting to fool us) about the nature of the regime they defend, and consort with. Perhaps our leaders are no worse than, say, British Cabinet ministers in the 1930s who enjoyed hunting with Hermann Goering, but if that is the standard they are comfortable with, New Zealand is in an even worse place than I’d supposed. In their book, Gilbert and Gott quote from the former head of the British foreign service:

“Looking back to the pre-1939 era Vansittart wrote: “I frequently said that those who ask to be deceived must not grumble if they are gratified”

Indeed.

I said that I thought Professor Brady was inclined to pull her punches a bit. Asked what New Zealand can do, she began her response claiming that “Australia can be more forceful”. No doubt Australia is, and will remain, more forceful – we’ve seen in the DFAT Secretary’s speech, in the ASIO report, in the foreign affairs White Paper, and in the new legislation details of which were announced yesterday. But “can” isn’t the operative word. If trade is your concern, Australia trades more heavily with China than New Zealand firms do. If distance is your concern, Australia is physically closer to Asia – and the waterways of the South China Sea. Our political leaders – National, Labour, New Zealand First, Green – could speak out, could act forcefully. But they won’t.

Shameless and shameful.

UPDATE: As I pressed publish, I discovered that I’d been sent a link to some other reflections on Peters and Haworth by China expert Geremie Barme.