I gave a talk in Nelson last night on housing issues. It was largely a rework of material I’ve used before (posted here and here) so I won’t post the text here. I’m not sure the speech quite hit the mark for the audience, but as always when I put together a presentation I find that I learn something in the process, or some things come together more clearly in my own mind.

By Auckland standards, Nelson-Tasman house prices aren’t that high. In real terms, house prices are still lower than they were in 2007. But a median house price of around $400000 against a median household income of not much over $60000 reminds us just how high price to income ratios are across most of New Zealand (my old home town of Kawerau remains an unattractive exception). Most of the “problem” is in the land.

As I often do, I devoted a bit of time to explaining why I don’t think features of the tax system are a material part of the explanation for high New Zealand house prices, or for the cycles that we – and other countries – experience. As a slight counterbalance, I took the opportunity to put in another plug for land-value rating by local authorities, a case also recently made by the Productivity Commission. Most New Zealand local authorities now use capital value rating, which – relative to a land value base – provides less of an incentive to bring vacant land into development. In principle, and all else equal, greater use of land value rating should help to dampen urban land prices, and close the gap between rural and peripheral urban land prices.

But one of the audience, a highly-respected figure in Nelson, with decades of experience in the building industry and on the local council, pointed out to me that Nelson city had, some decades ago, moved to land value rating. Urban land prices remain very high. It isn’t obvious that land value rating has been very helpful in easing land supply pressures. Then again, nothing operates in isolation. Neighbouring Tasman District Council, where much of the (flat land and) population and housing growth has been, still operates a capital value rating system. And an ever-growing District Plan, that now runs to 1000 pages in Nelson City, probably has not a little to do with the continuing high land prices, and the continued excessively costly houses, in that part of the country.

A variety of factors no doubt explain the shift to capital value rating, although one can’t help wondering if the pervasive biases of so many councils towards more intensive, rather than extensive, development isn’t part of the story. Many councils really don’t seem to want more land developed, or they want it developed only at a pace that suits them. It is probably unrealistic to think that councils would favour a move back towards land value rating when those same councils are the ones applying land use restrictions in the first place. If councils were committed to making urban land affordable, they could quite readily do it now. Instead, as the Productivity Commission put it – seemingly approvingly – in its report last week:

Many urban councils in New Zealand have a clear idea about how they want to develop in the future, and how they intend to meet a growing population demand for housing. Many larger cities have chosen to pursue a compact urban form. Yet some of our cities have difficulty in giving effect to this strategy”.

Sadly, the Productivity Commission seems to see councils, and the planning regime, as part of the solution rather than as a large part of the problem.

I hadn’t been thinking much about housing while I was on holiday, but a conversation with friends we were staying with, in their growing prosperous (2 per cent unemployment rate) Midwest small college city, had got me thinking. I’d asked about local house prices and they’d commented that their house was probably worth about US$175000 – decent-sized section, four bedrooms, and five minutes walk from the local college. And they observed that prices had been moving up, and local sentiment was that they were really quite expensive. In exchange I offered them scare stories about Island Bay prices, and vague references to the scandalous Auckland prices.

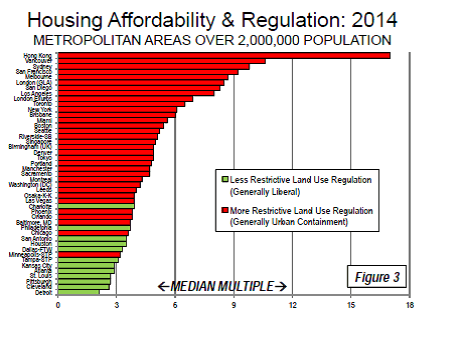

I didn’t give it much more thought until I got home and started preparing last night’s talk. That observation that US$175000 was quite expensive was still running round in my head, and so I printed out the latest Demographia tables. I’ve often used Houston as an example of a large, fast-growing, city with very moderate house prices – in fact, lower in real terms than they were 35 years ago. But, actually, Houston prices aren’t at the low end of the range – the median house price was about US$200000 there last year. Astonishingly cheap, absolutely and relative to income, by New Zealand standards but not by US standards. Detroit (inner city) is a byword for cheap, but among cities with over a million people (and remember that Auckland hasn’t that many more than a million), these places last year had median house prices in a range of US140-175K (and price to income ratios of around 3).

Cincinnati

Grand Rapids

Pittsburgh

St Louis

Atlanta

Indianapolis

Kansas City

Louisville

Columbus

Oklahoma City

Memphis

Tampa

And there are dozens of other similarly affordable smaller cities. I haven’t checked each of them, but I suspect “densification” hasn’t been a big part of keeping housing affordable.

Of course, the US has places at the other end of the range as well – places I’ve barely heard of as well as Los Angeles, Honolulu, San Diego, San Francisco, and so on.

What marks out one group from the other isn’t being a “global city”, or a growing city: it is mostly the land-use restrictions. As Demographia highlight, there are no cities with high house price to income ratios that have liberal land-use regimes.

Which brings me back to a speech given last month by Bill English on housing affordability. I noticed it has even been getting some coverage abroad, and it certainly has some useful perspectives on some of the issues (although looking through my copy I noticed I’ve scrawled “dubious” in a surprising number of places). I liked the idea that our Deputy Prime Minister was making the case that urban planning has become a net drag on the country, and especially on its poorer and more vulnerable people, for whom housing has become progressively less affordable. I was surprised to learn that the government now subsidises 60 per cent of all rentals in New Zealand. And as the Minister notes of the 3000 page Auckland Unitary Plan “no one person [ or, one might add, no committee or Council] could possibly understand all the trade-offs in that plan”, or the implications of those choices.

I did, however, splutter at the suggestion that planning was an externality that central government might have to deal with just like “other externalities, such as pollution”. The Minister seems to conveniently forget that the powers local governments have all flow directly from central government legislation – the centrepiece of which, the Resource Management Act, was passed by a government in which he served as junior backbencher. Individual members of central and local governments may have their hearts in the right place, but this is ultimately a problem of central government failure at least as much as of local government failure.

And there are few signs that the problems are going away. But perhaps that shouldn’t surprise us. As I’ve noted here previously, I’m not aware of any examples of places in advanced economies where tight land use restrictions once in place have ever sustainably been removed. When I first made this observation, I made it pretty tentatively. I’m not an expert in the details of urban planning or familiar with the hundreds of individual regimes in various countries. I was half-expecting that someone would come back to me quite quickly pointing me to a compelling case study of successful liberalisation. So far no one has. And I haven’t heard the Minister of Finance or the Minister of Housing highlight such studies. I haven’t seen the New Zealand Initiative do so, and I haven’t seen Demographia do so, even though they have every incentive to highlight such examples if they exist. I still hope there are such case studies out there, but it looks increasingly unlikely.

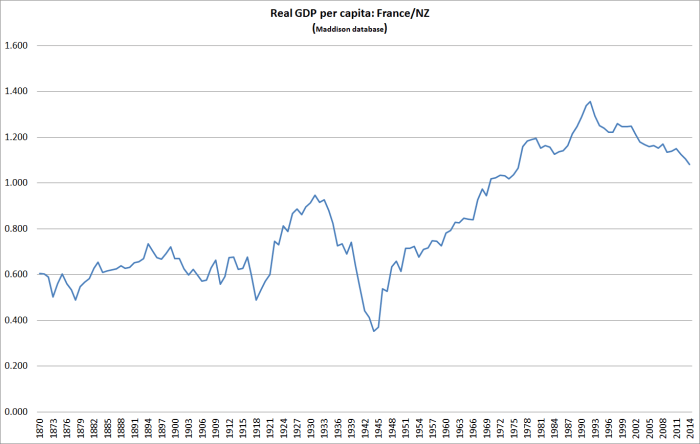

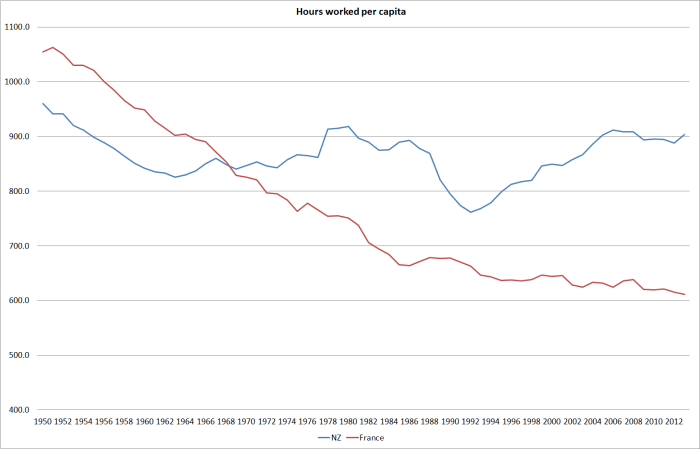

Bad policies don’t last for ever, but they can carry on for a very long time. I highlighted last night that New Zealand once had the unique feature of a car market where second-hand cars held their value and (by repute at least) were at times worth more than new cars. My maternal grandfather often liked to tell the story that he reckoned my father was keen on marrying my mother as much because she owned a car as anything else (she’d done an OE and had overseas funds). The insanity of the import licensing and local assembly regime eventually came to end, but it took a very long time – sixty years or more. Is there any reason to be more optimistic that housing will once again be affordable in New Zealand any decade soon? If house prices had been bid up simply on the back of reckless bank lending policies, then perhaps so. But that isn’t the New Zealand story. Ours is a story of microeconomic policies, implemented and maintained by successive central and local governments, with the clear and predictable effect of making housing, and the sort of housing people want, much less affordable than it needs to be.