I urged again the other day that there should be an open process of research and debate leading towards the negotiation of the next Policy Targets Agreement in 2017. These documents matter. Monetary policy is the main tool for short-term macroeconomic stabilisation, so the PTA sets the “rule” (well, loose guide) for how the short-term fluctuations in the economy will be managed. The Reserve Bank – and the Treasury and Minister – has often had a tendency to treat deliberations around the PTA as technocratic in nature (which in some ways they are), and hence not something with which to trouble the natives. The standard Reserve Bank response to any suggestion of greater openness was “but we already tell them what we want them to know”. But open government is not just about releasing finished products, after the event, in bureaucratically-approved formats.

Two other former Reserve Bank staff, Kirdan Lees and Christina Leung, both now at NZIER, have made a useful contribution to a debate about the future of New Zealand’s monetary policy. They put out a note the other day headed Time to reassess inflation targeting, which concludes with a pretty strong leaning towards adopting nominal income targeting instead. I don’t think they will get far with the current Governor on that one – he used to bristle and react very frostily whenever anyone so much as mentioned nominal income targeting – but he won’t be Governor for ever, in the end the Minister of Finance calls the shots, and whether the Governor likes debate or not, it is an important part of good public policy processes.

However, I’m not convinced by the Lees/Leung argument. In particular, I’m not persuaded that the form of the rule makes a great deal of difference to assessing the appropriate stance of monetary policy now. Nor am I convinced it would have made a great deal of practical difference over the pre-recession years. And if we were going to move away from inflation targeting, I’m not convinced that nominal income targeting is the alternative I would adopt.

Lees/Leung have a number of strands to their argument.

First, they argue that “supply shocks” have become more important relative to “demand shocks”. Perhaps, but where is the evidence for that proposition in New Zealand or in other countries? They seem, in part, to be arguing from the presence of a number of phenomena (fracking, the internet etc) which are improving productivity. All of them are real, but in aggregate productivity growth has been materially slower in the last half dozen or so years than in the previous decade. And, in any case, the issue for monetary policy would not normally be the trend rate of productivity growth, but shocks – surprises, which can go either way. There is, of course, one area where supply shocks have become more important for New Zealand – terms of trade volatility has been much greater in the last decade than in the previous 15-20 years (apparently driven mostly by the fairly extreme dairy price volatility). We’ll come back to terms of trade shocks.

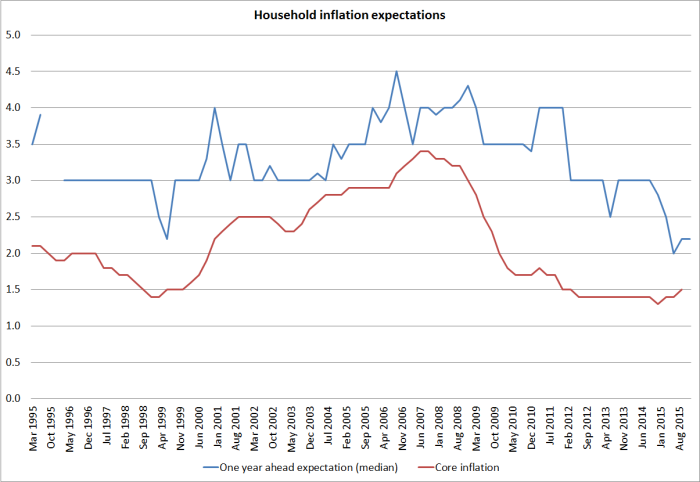

Second, they point out that many advanced countries have seen inflation undershoot respective targets. That is, of course, true, but most of the countries on their chart have largely exhausted the potential of conventional monetary policy. Interest rates are basically at zero, and have typically been so for quite a few years. There are reasonable arguments that a different target might make it a little easier to get out of the current “trap”, but they aren’t relevant to New Zealand at present. Our Reserve Bank has undershot the inflation target not because it couldn’t cut interest rates enough, but because it chose not to. That failure probably wasn’t wilful – largely it was because they misread the data. They (and other central banks) misread the data on the other side during the boom years. Forecasting is difficult, but it is a problem that bedevils any of the rules under discussion.

Third, they point out the well-known proposition that, in principle, nominal GDP targeting can generate better short-term macroeconomic performance (eg less output variability) in the presence of supply shocks. In the example they cite, faced with drought, an inflation targeting central bank will tend not to adjust policy (since inflation, and especially core inflation, won’t change much) while a nominal GDP targeting central bank will tend to ease policy to lean against the drought-induced fall in GDP. But, in fact, whichever rule was adopted, the central bank would almost certainly be reacting to forecasts (whether of inflation or nominal GDP), since monetary policy only works with a lag. Droughts typically aren’t recognised by central banks until we are in the midst of them, and when they are recognised they are typically assumed to be shortlived. Faced with the prospect of a drought this summer, the Reserve Bank will typically (and reasonably) assume that next summer will be normal, and since monetary works with a lag they wouldn’t change policy under either regime.

Fourth, they argue that the difference between inflation targeting and nominal GDP targeting is quite material for where the OCR should be set right now. It is certainly feasible that in some circumstances there could be quite a difference, but they don’t make a persuasive case that this is one of those times.

They compare inflation rate targeting with nominal GDP level targeting. Either prices or nominal GDP can be targeted in rate of change terms (inflation rates) or in levels terms. No country in modern times has adopted levels targets for either prices or nominal GDP. The Bank of Canada looked quite carefully at the option of price level targeting a few years ago, and concluded that it would not represent an improvement over inflation targeting. One reason levels target don’t appeal to practical policymakers is that if one makes a mistake and prices or nominal GDP rise unexpectedly strongly, one can’t just treat bygones as bygones – one has to tighten to drive the level of prices (or nominal income) back down again. Whatever the theoretical appeal of such an approach, it seems unlikely to command much public enthusiasm or support – and hence seems unlikely to prove durable.

Much of the older literature around nominal GDP targeting was done in terms of rates of change (nominal GDP growth rates). But since the 2008/09 recession there has been renewed interest in the idea of a level target for nominal GDP. The argument made, most prominently by US economist Scott Sumner, has been that a target for the level of nominal GDP would have (a) prompted an earlier easing in monetary policy, and (b) would underpin expectations (especially in the US and Europe) that interest rates would stay low for a long time.

Lees/Leung acknowledge that the current inflation targeting framework invites further cuts in the OCR (we’ll see next week whether the Governor agrees, although recall that it is a forecast-based framework, so OCR cuts aren’t warranted if the Bank can convincingly show that core inflation is heading back to 2 per cent reasonably soon on current policy). But then they suggest that using nominal GDP levels targeting “interest rates are about right”.

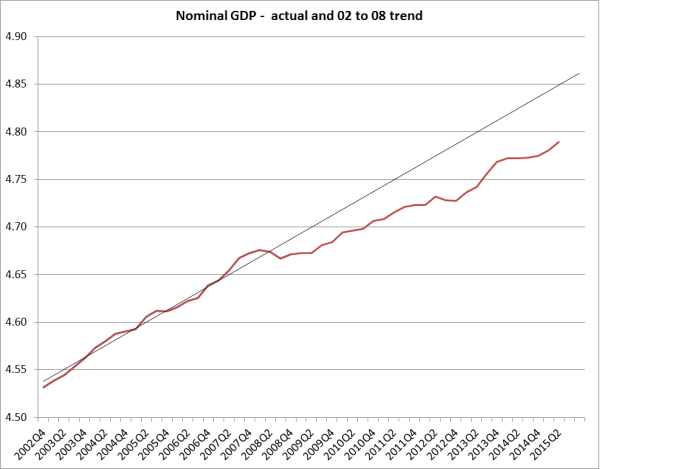

They appear to base that observation on this “illustrative example”.

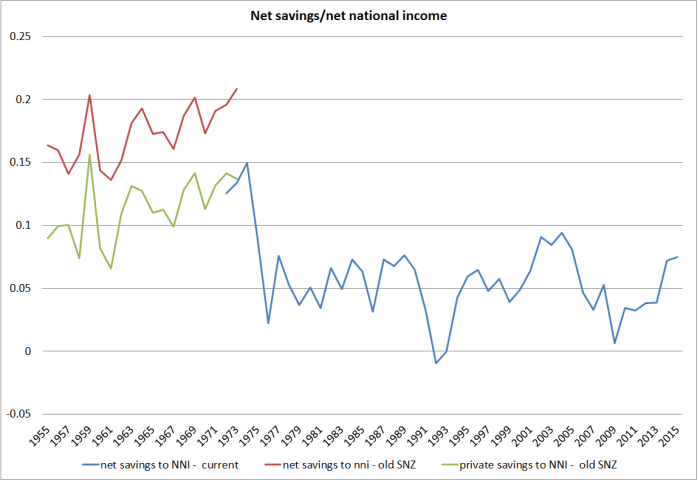

In this chart, they appear to have simply drawn a trend line through actual nominal GDP since 1998 and then calculated the difference between the trend line and actual. That difference is small.

But to adopt a nominal GDP levels target, one would need to define an appropriate trend period first. And it isn’t clear to me why this is the right one. Most advocates of nominal income targeting at present argue for using something like the pre-recession trend (since the arguments are about whether policy has been sufficiently loose in the year since 2008). In a New Zealand context, in both 1996 and 2002 policymakers decided that New Zealand should have a faster trend rate of nominal GDP growth (since they revised up the inflation target). Alternatively, a common approach in New Zealand has been to look at the entire period since low inflation (and lowish nominal income growth) was established, around 1992.

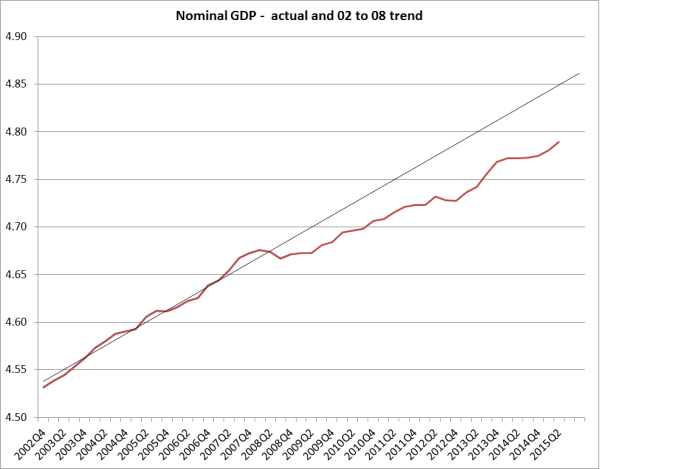

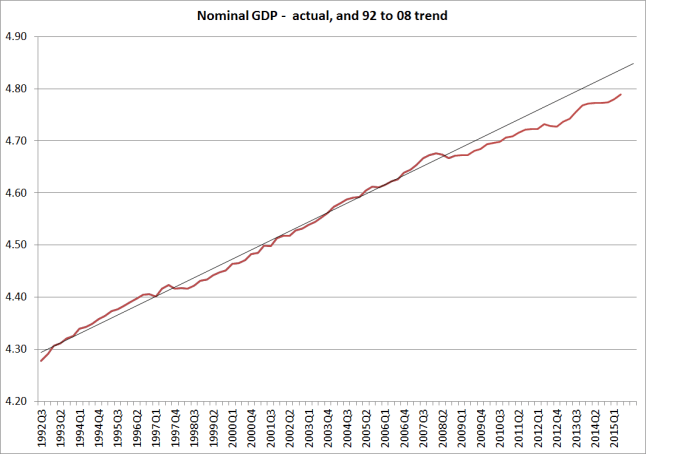

I’m not sure that a trend starting from 2002 to, say, 2008, is that enlightening. After all, there was a common view that monetary policy was too loose over at least several years of that period (Alan Bollard has openly acknowledged as much). But if we used that as the trend, this is what the picture looks like (using logged data).

Nominal GDP is well below that pre-recession trend (as it is in most countries), arguing for looser monetary policy now as well.

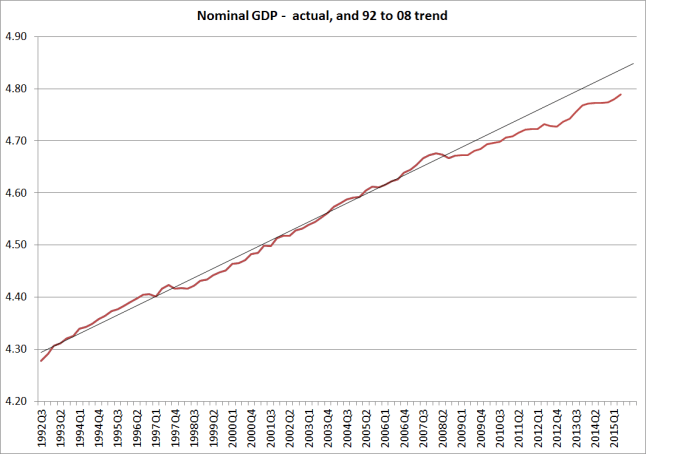

Or we could use a trend done over 1992 to 2008 and one ends with a similar gap.

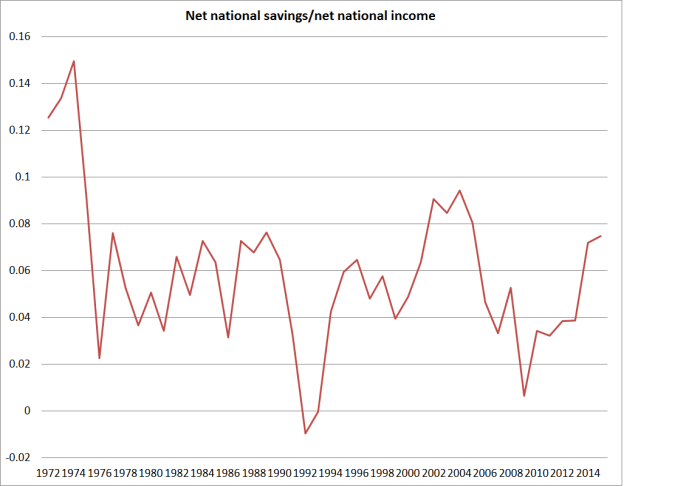

Levels targeting does require identifying a starting level (which is neither easy nor uncontentious). But what if we just look at nominal GDP growth rates?

Not only has nominal GDP growth averaged far lower since 2008 than it did over the previous 17 years, but the most recent observation (annual growth of 3.9 per cent) is right on the average for the post-2008 period. If we are happy with something like 2 per cent inflation (few have argued for lowering the target) and have a population growth rate of almost 2 per cent per annum, then 5 per cent nominal GDP growth might be a reasonable benchmark. Current nominal GDP growth is well below that, just as current inflation (headline or core) is well below the 2 per cent inflation target.

So, shifting between CPI or nominal GDP based rules, levels or rates of change, looks as though it would not make much difference to how one thinks about appropriate monetary policy at present, at least on the current data.

But as I noted earlier, central banks aim to base policy on forecasts, so the issue is not so much where inflation or nominal GDP is right now, but where the central bank thinks it will be in a year or two’s time. My proposition is that most of the mistakes central banks have made in the last decade or two have been forecasting mistakes rather than policy rule mistakes. Monetary policy wasn’t tightened soon enough during the boom years partly because Alan Bollard was a dove, but partly because the Bank – and most other forecasters even more so – recognised the immediate inflation pressures, but forecast that they would soon dissipate. They were wrong, and as a result inflation and nominal GDP growth were higher than forecast. Similarly in the last few years, central banks have underestimated how weak both inflation and nominal GDP growth have been. If one could forecast nominal GDP more reliably than inflation, perhaps the case for change would be stronger, but outside recessions the big source of fluctuations in New Zealand’s nominal GDP is international commodity prices. They are highly volatile, and the volatility dominates any trend movements over the sorts of period relevant to monetary policy.

An international conference was held in Wellington a year ago this week to mark 25 years of inflation targeting, and the papers have recently been published. Several academics presented a paper looking at how inflation targeting compared with nominal GDP targeting for New Zealand. They looked at a variety of different time periods, including the pre-liberalisation period, the transition to a more liberalised economy, and the current period. The authors were sympathetic to the case for nominal GDP targeting. I was asked to be the discussant, bringing a practical policy perspective to bear on the issues raised in the paper. In my remarks, I set out some of the reasons why I’m not convinced that a practical nominal GDP rule would represent a material advance over (practical) inflation targeting.

One of the attractions of nominal GDP targeting is that it prompts a monetary policy tightening when export commodity prices rise, even if there is no immediate rise in consumer prices. But as I noted one needs to think specifically about the characteristics of the particular economy.

In thinking about an export price shock, it might also be important to understand the transmission of the shock across the rest of the economy. A highly open economy, in which a generalized export price shock affected firms across an employment-rich wide-ranging export sector, might look considerably different than a sector-specific shock in a moderately open economy where the commodity production sectors employ relatively little labor (the story in New Zealand dairy, and much more so in Australian minerals and gas extraction). If New Zealand experiences a surge in dairy prices, and much of the proceeds are saved by farmers—perhaps because they are very conscious of the volatility of prices—why would one want to tighten monetary policy against that lift, if there was little or no apparent spillover to domestic (wage or price) inflation? Perhaps if the shock destabilized wage expectations there could be a basis, but there has been little sign of that sort of wage-setting behavior in response to recent export price shocks. The issues are even more stark in Australia, where most of the profit variability in the face of export price shocks accrues to non-Australian owners of capital (whose consumption choices are likely to put few pressures on domestic resources in Australia).

Partly for this reason, over several years I have been drifting towards the conclusion that if one were to replace inflation targeting with another rule, in New Zealand’s case nominal wage targeting might have rather more appeal. I noted

Much of the academic discussion of inflation targeting focuses on the idea of stabilizing the stickier prices in order to minimize the real costs of adjustment to shocks. Since, as this paper agrees, wages are typically among the stickier prices, perhaps we should be more seriously considering the merits of nominal wage targeting, as Earl Thompson argued decades ago. I have noted elsewhere (Reddell 2014) that such a rule could even have financial stability advantages. Nominal wages are the prime basis for servicing the nominal household debt that dominates the balance sheets of our banks. Faced with adverse shocks, and especially deflationary ones, nominal debt is arguably the biggest rigidity of them all. It would be interesting to see such a rule evaluated in a suitable model.

But…..

If productivity shocks were the dominant source of dislocations in New Zealand, such a wage rule could also have considerable appeal— shifting the variability into the price level rather than into (sticky) nominal wage inflation. As it is, over the last twenty years, wage inflation has followed a rather similar path to core CPI inflation— and does not look much like fluctuations in the path of nominal GDP (or in NGDP per capita, or NGDP per hour worked). So perhaps, at least over that period, policy should have looked very little different under a wage rule than under the CPI inflation targets that successive ministers and governors have agreed upon.

Of course there might be considerable political/communications difficulties with wages-targeting. But this would be nominal wage targeting: actual real wages and the labour share of income would still emerge from the market process. But given these communications difficulties, the case for change would have to be stronger than it is right now (although for what it is worth, current wage inflation also probably argues for looser monetary policy – just like the CPI or nominal GDP).

I have little doubt that inflation targeting is not the “end of history” for monetary policy. But the choice between inflation, nominal GDP, or wage targets – in levels or growth rate terms – doesn’t seem to be the biggest issue we face in designing monetary policy and the related institutions. In practical terms, each would rely on forecasts, and our forecasts simply aren’t very good. And each still faces the issue of the near-zero lower bound. There are arguments that levels targets might help alleviate the ZLB, but only zealots think that in isolation it would make a huge (or sufficient) difference. We need much more energy being applied to either removing the ZLB constraints (which are essentially regulatory in nature) or raising the target for inflation (or nominal GDP or wages growth) sufficiently so that the zero bound is no longer likely to be binding. The Bank of Canada is right to be looking at this issue. Other central banks and finance ministries need to be doing so.

And I still think the other issue is one of just how much accountability there can actually be for autonomous central banks implementing monetary policy. As I have noted recently in both the New Zealand and US contexts, in practical terms there is very little. In the United States, John Taylor has argued for legislating something like a Taylor rule as a benchmark against which the Federal Reserve’s judgments can be formally evaluated, requiring the Fed to explain deviations from the recommendations of that rule. Some on the political right argue for a return to the Gold Standard. I don’t think either would be desirable, but in a sense both are reactions against the delegation of too much unchecked power to central banks. The original conception in New Zealand was of a high degree of effective accountability – an easy test as to whether or not the Governor has done his job. Money base target ideas had a similar conception – plenty of delegation, but plenty of effective accountability. It turned out not to be so easy. But if we cannot meaningfully hold these powerful independent agencies to account – in ways that mean real consequences for real people – I suspect the debate will begin to turn again as to whether the power should be delegated to unelected officials at all. Citizens can vote governments out of office, and that has real consequences for real decisionmakers.