(And other economics agencies of government, but the Reserve Bank should be the highest priority given the extent of the decline and the substantive importance/powers of the institution.)

On Friday my post focused on the (severe) limitations of the members of the new Reserve Bank Board. Together, they look as though they would be a well-qualified (perhaps a touch over-qualified) group for the board of trustees at a high-decile high school……but this is the central bank and prudential regulator.

I had a couple of responses suggesting that, if anything, I was pulling my punches, understating the severity of the situation, when it came to the Reserve Bank. One person, who preferred to remain nameless (having high level associations with entities the Bank regulates), indicated that I was free to use their comments provided it was without attribution. These were the comments:

The situation is parlous: inept, multi-focussed but wrong focus, terrible judgement, appalling hires, complete absence of appropriate governance, woeful expertise, [backside]-covering of the regulator rather than interaction. I have zero confidence in their leadership, judgement, processes, balance of hires, and particularly governance which has been enabling of dross.

I guess the Governor could, in response, point to the recent NZ Initiative survey (of the regulated) suggesting the Bank’s standing among that community had improved in recent year (it was never clear to me why, other than the decision to move one key individual who had had significant responsibility for prudential policy).

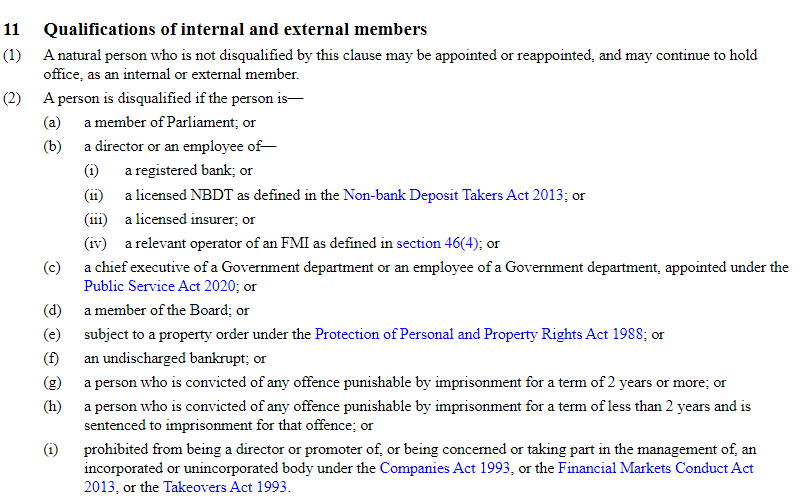

So views will differ, and if – based mostly on what we all see – my views are a bit less harsh than those of some, it seems clear to me that there is a significant problem, and that with the new Board appointments the situation is worsening. The entire new governance and decisionmaking structure – overhauled over several years – is now in place with an MPC where serious expertise is explicitly a disqualifying factor for appointment as an external member (the people who are supposed to represent a check on management), and a Board where in practice serious subject matter expertise (financial stability and regulation or macro) also seems to have been treated by the minister as a disqualifying factor. And all this with a senior management team that is inexperienced (3 of the 4 internal members) or in the case of the Governor mediocre on a good day and more interested in other things (“patently inadequate” for the job was the stronger description of my commenter). Oh, and a Minister of Finance who doesn’t seem to have much interest in building excellent institutions or achieving excellent policy outcomes, who falls short of the standard citizens should be entitled to expect.

What we don’t know is how the National Party Opposition see things. They and their partner now lead in the polls and seem to have a pretty good chance of forming a government after the next election. Since Simon Bridges late last year, just after becoming the Finance spokesperson, said that National would not back reappointing Orr and was shut down within hours by his new leader, we’ve heard nothing much at all from National. You get the sense that the Governor is not exactly their cup of tea, but what (if anything) do they propose to do and say. They (and the other parties) were required to be consulted on the Board appointments. But whether they were happy, or pushed back vigorously, we have heard not a word from the new Finance spokesperson. Silence risks counting as (perhaps resigned) assent.

The Governor’s current five-year term expires in late March next year (ie less than 9 months from now). The process for filling the slot is likely to be getting underway very soon, and it would surprise me if the government (and the Bank) did not want to have everything resolved before Christmas. Under the Act, the Minister can turn down any candidate the Board nominates, but the Minister cannot impose his or her own candidate – ultimately whoever is appointed must be nominated by the Board. There is, of course, nothing to stop the Minister telling the Board in advance that he would not accept a nomination of a particular person or class of persons. In practical terms, there is also nothing to stop the Minister telling the Board who he might like them to nominate – although with a capable and independent Board that approach would risk backfiring.

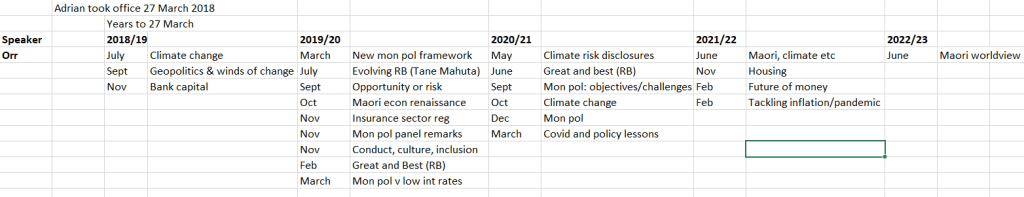

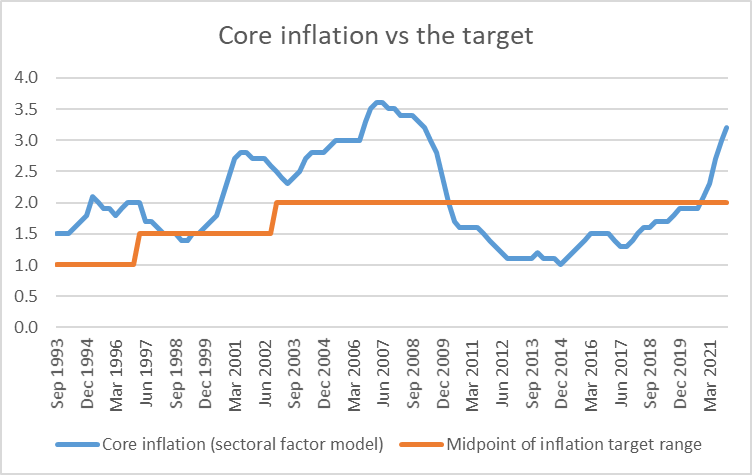

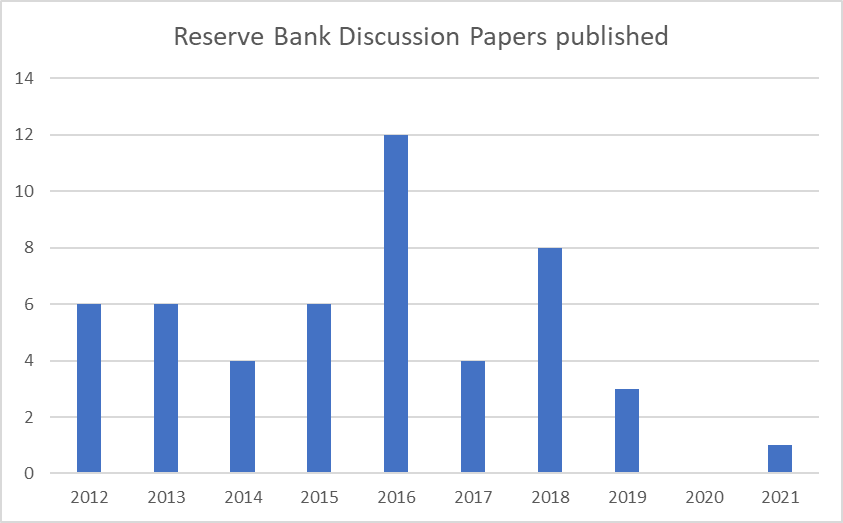

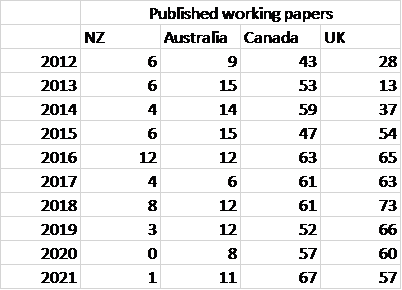

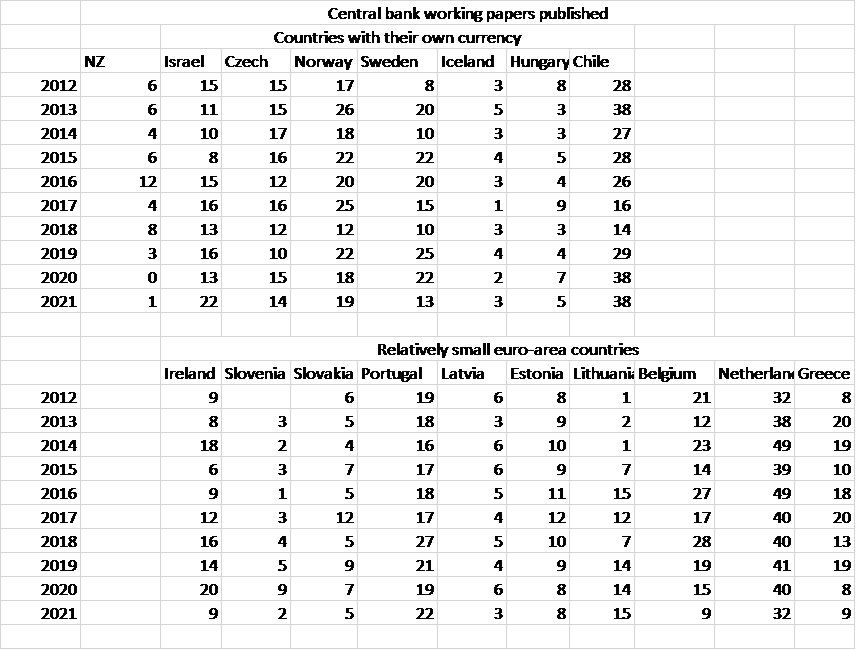

Most RB-watchers treat the reappointment of Orr as pretty much a foregone conclusion (assuming the Governor has not found greener pastures in which to labour). At present, I agree. But that is partly because of the silence where one might have hoped there was an effective political Opposition. If National is content to resign itself to another five years of Orr – using his platform as head of a technocratic non-partisan institution to champion personal left-wing causes, operating with his bullying and divisive style, presiding over a sharp downgrading of the Bank’s research and analysis capability, losing billions of dollars for the taxpayer and then (together with the surge in core inflation) brushing it all off with a “I have no regrets” – they should just keep right on as they are.

But if they aren’t content, they should be saying so, forcefully and often, now. If Labour really insists on reappointing Orr, there is not much formally that can be done to stop it – a brand-new board, selected in part by Orr, is simply not going to decline to recommend reappointment. The only chance of him not being reappointed (assuming he still wants the job) is for Labour (Robertson) to decide it isn’t worth it for Labour to continue to back Orr. We should hope for Governors who are broadly acceptable across the spectrum (not necessarily the ideal candidate for the other side, but broadly tolerable nonetheless) – after all, they wield a great deal of power, can’t easily be dismissed, and Labour itself inserted the new clause in the law requiring the Minister to consult other political parties in Parliament before appointing a person as Governor. “Consult” does not mean “obtain consent or support”, but in a context like this it should mean “take seriously very strong opposition, especially from a range of parties, or perhaps from the largest other party”. It was, after all, Labour that just introduced the provision. But waiting until December to privately express concern is a pathway towards just being ignored – by then the reappointment process would have a lot of momentum behind it already. Now is the time to start speaking out, carefully but forcefully. If they care.

In the New Zealand system, most official appointees have fixed terms and cannot simply be dismissed and replaced immediately by a new government. Mostly, that is a good thing. The position of Governor of the Reserve Bank is one of those positions. So, it seems, are appointees to the MPC and the Board.

Each of these individuals or classes of people can be replaced at any time, but only “for (just) cause”, and what counts as “just cause” is defined in the Act. In the case of the Governor

The provisions around removal the Governor from office seem more tightly drawn than they were under the previous legislation (which may have something to do with the formal responsibility for many things the Bank does having been shifted to the Board).

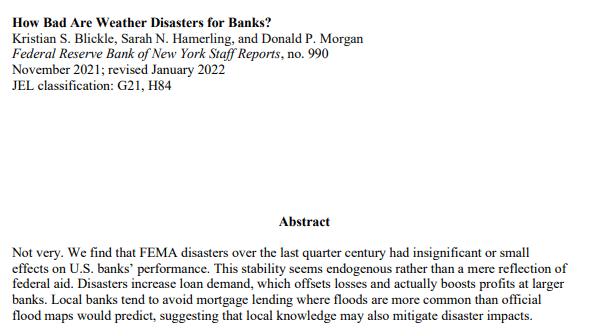

Much as I am critical of a lot of what has happened at the Bank during Orr’s tenure, none of it (individually or collectively) adds up to enough to represent a credible basis for removing him. Are $8bn of LSAP losses dreadful and without excuse? Sure, but it was the Minister of Finance who agreed to the policy and the risks. Is it bad that inflation is at about 7 per cent? Sure. Could the Bank have prevented core inflation getting above 4 per cent? Most probably, and I think there should be searching criticism of the Bank’s failure, and lack of transparency/accountability. But it just isn’t enough to sack a Governor mid-term, especially when (a) so many other countries are seeing something similar, and (b) the median market economist/commentator wasn’t much better when it mattered (last year). One might reasonably lament the decline in the analytical and research output, some poor appointments and massive losses of senior staff. One might lament the diversion of focus onto non-central banking things like the tree gods and climate change. But no one is ever going to sack an incumbent Governor mid-term over such failings (and the Minister often seems to have welcomed the diffusion of effort), bearing in mind the risk of being judicially reviewed, and the attendant lengthy period of (market) uncertainty. It just won’t happen (and probably shouldn’t).

Which is why, if National were to be seriously bothered about Orr they need to be speaking out now and focusing on the looming reappointment.

Fortunately, even if reappointment is the key, there are other levers for promoting change. The Monetary Policy Committee’s Remit can be altered (and, no doubt, the forthcoming financial policy one), including to take out the woolly and irrelevant (to monetary policy) references to sustainable and low carbon economies. National is proposing to delete the employment limb of the target (on this, I agree with the Governor, that the amendment adding it hasn’t made more than cosmetic difference, and nor would reversing it). Ministerial letters of expectations aren’t binding, but they are one more lever, and a new government could make clear from the start that it expects the Bank to focus on its core responsibilities, expects a lift in the quality and range of research outputs etc. The Minister could also amend the rules around the MPC to, for example, require individual votes and reasons for those votes to be disclosed, and to create an expectation that individual MPC members could be expected to make speeches, give interviews, front FEC, and generally be accountable for their view. Small legislative changes to move the responsibility for MPC appointments purely to the Minister (not mediated by the Board) would also be a step in the right direction, weakening what is now a heavy degree of gubernatorial control over monetary policy and the committee.

And then there are the appointees themselves. By the time a possible National government takes office, Orr may be just 6-8 months into a second five year term. But quite a few of the new Board members have been appointed for terms that expire in mid-2025. A new government should begin looking early for high quality people, with strong subject expertise, to replace them. And what of the MPC? There are three external members. One has a term that expires next April, and will have either been reappointed or replaced by the current government. But one member – Peter Harris, who has had close Labour Party associations – has an extended term expiring next October. That should be a date that disqualifies a permanent appointment being made prior to the election (it still puzzles me why Labour chose that date – he could easily have been extended for 2 years rather than 18 months). And the final member has a term expiring in April 2025. It should be made clear to all involved that there will no longer be a bar on appointing people of demonstrated ongoing excellence and capability in macroeconomics and monetary policy, and that the Minister would have a strong preference to appoint at least one such person at the earliest opportunity.

And then there is the budget. The Bank is an unusual government agency, in that it is not funded by annual appropriations (in the way many important – with aspects of independence – agencies are) but through a five-yearly funding agreement, governing how much of its own earnings can be used as operational spending. There are a number of flaws in this procedure but it is what it is, for now at least.

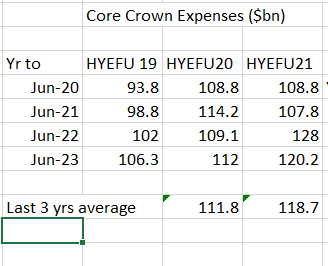

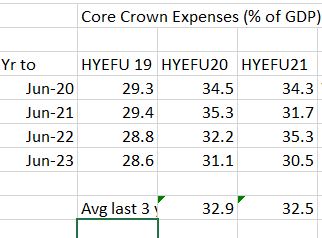

The Bank was given a massive increase in funding in the agreement approved in 2020. But one of the interesting (broadly incentive-compatible) aspects of the arrangement is that permitted spending is specficied in nominal terms for five years. Above target or unexpectedly high inflation makes nasty inroads on the Bank’s real capacity to spend. As wages and salaries rise faster than originally allowed for, that bite is likely to be coming on soon. Moreover, although the agreement wasn’t signed until late Feb 2020, by the time a possible new government takes office (say next November) the Bank will be very conscious that the next round of negotiations will be looming before too long. The final year covered by the current funding agreement is 2024/25, but if you were the Bank (management and Board) you would be wanting some clear signals from the Crown fairly early as to how much the Bank might have available to spend in the following five years. An early signal (say by the time of the 2024 government Budget) from an incoming Minister of Finance that s/he was minded to materially reduce real Reserve Bank spending in the future funding agreement would affect choices the Bank was making from them. National seems to be struggling to identify expenditure savings, and while the Reserve Bank is not that big in the scheme of things, it is much bigger and more expensive that it was five years ago, and ripe for trimming down. The basic functions of the Bank haven’t changed, but the size of Orr’s empire has blown out. It should be pulled back. Ideally, the legislation should be amended to allow the Minister to better specify what money is spent on, but it should be made clear to the Governor and the Board that the Minister expects a ruthless focus on core functions (not, eg, a proliferation of comms or climate change people). The office of Governor might be much less appealing to someone like Orr if he was compelled to manage in that way. That, on this scenario, would not be a bad thing.

And all this without even touching on those mind-numbing documents like the Statement of Intent. The Minister can require a new Statement of Intent at any time, and the Bank must take seriously (“consider”) the Minister’s comments on a draft.

All this is by way of saying that while, if National cares about the Bank, it should focus now on building a climate where it is not worthwhile for Labour to stick by Orr (or where if they do it just looks like a poor and partisan appointment), there are plenty of avenues open to a new Minister to put pressure on to constrain the Governor’s behaviour, his dominance of the MPC process, his empire, his focus, his style and so on. But a new Minister has to want change, and be prepared to follow through consistently.

Finally on the Bank, it is fair to note that it is one thing to argue that Orr should not be reappointed, but quite another to identify an excellent potential replacement. There are no immediately obvious potential nominees of the stature required to begin credibly rebuilding the institution (Bank and MPC). That itself is a poor reflection on the way the Bank has been run for at least the last decade (contrast say the RBA or the Bank of Canada), and perhaps symptomatic of wider weaknesses now at the upper levels of the New Zealand public sector more generally. But just because there is no obvious single name now, isn’t a reason to stick with such a poor incumbent (and if there isn’t an obvious replacement, I can think of several who could, at least as part of a new team, do the job, and we should at least be open to the possibility of a foreign Governor (even if such an appointment might be less easy than it sounds)).

This post has been focused on the Reserve Bank. But there are other agencies a new Minister of Finance will have to pay attention to. There is little point expecting different outcomes if you leave the same people (and sorts of people) in place (and there is a wider question there about what sort of person a new government will replace Peter Hughes, the Public Service Commissioner) with in mid 2024). But the open question still is whether National really cares much about different outcomes, or is primarily interested just in gaining and holding office. Voters might like some idea of the answer.