I’ve been working my way through a series of posts on the post-2007 economic experience of a large number of advanced countries, with a particular focus on trying to make some sense of New Zealand’s (no better than middling) experience.

Today I wanted to have a quick initial look at the incidence of financial crises, since the shorthand for what has gone in recent years has often been “since the financial crisis” or “since the [so-called] GFC”. Many authors, including some pretty serious and respected ones, have ascribed much of the poor economic performance to the “financial crisis”, adducing the experience as evidence supporting a case for much tighter regulatory restrictions all round. And there are plenty of theoretical discussions as to how financial crises might have detrimental economic effects.

But what do we mean by a “financial crisis”? Many authors who try to classify events do so by looking at the gross or net fiscal costs of a crisis (eg the costs of bailouts, recapitalisations, guarantee schemes and so on). I’ve long thought that was a flawed basis for classification, for a variety of reasons:

- A country that allowed its banks to fail, with no bail-outs, might have no direct fiscal costs at all, yet on any plain reading could have experienced a very substantial crisis.

- Most (though not all) of any fiscal support for troubled financial institutions tends to benefit citizens of the country concerned, and so redistributes wealth rather than destroying it. There may be all sorts of adverse incentive effects, and deadweight losses from the taxes required to cover the fiscal costs, but the level of fiscal support is not a very meaningful indicator of the cost to society. In rare cases (eg Ireland) the fiscal costs themselves can become quite directly problematic, in terms of on-going market access, but that is not the general experience.

- A country’s banking system might be very highly capitalised, such that no banks actually failed even under severe stress, and yet on most reckonings the country concerned would have experienced a financial crisis.

- In some cases, banks will have experienced the bulk of their losses on offshore operations, while the intermediation business in the home economy might have been fine. The home government might choose to bailout the bank concerned, but there are few obvious reasons to think that those offshore losses (and the choice to bail) will have much effect on the home economy. A good example, in the most episode, was the losses sustained by German banks. On many classifications, Germany shows up as having had a financial crisis, and yet almost all of the increased loan losses resulted from offshore exposures (particularly in the United States housing finance market). If we are trying to understand the economic implications, it probably makes more sense to think of those losses as a US event than a German event.

So instead, I proposed a classification based on non-performing loan data, which the World Bank collects and reports by country. The proposition here is that, if there are sustained economic consequences from something we can label a “financial crisis”, they are likely to arise primarily from the initial misallocation of resources that led to the loan losses in the first place. Gross over-investment in a particular sector (say, commercial property in New Zealand in the late 1980s, or in Ireland in the last decade) eventually leads to losses. The projects don’t live up to expectations, and real resources devoted to those projects can’t easily or quickly be reoriented to other uses. Buildings lie empty, or even half-completed. If there are problems, they arise whether or not any bank ever fails, or is bailed-out by the state. And banks have to reassess their entire models for generating income, and are likely to become more risk averse as a result of the losses their shareholders faced. There might be additional costs if a large number of major financial institutions actually close their doors permanently after a crisis (that argument is part of the case for the OBR tool in New Zealand), but relatively few major institutions actually closed their doors in the period since 2007.

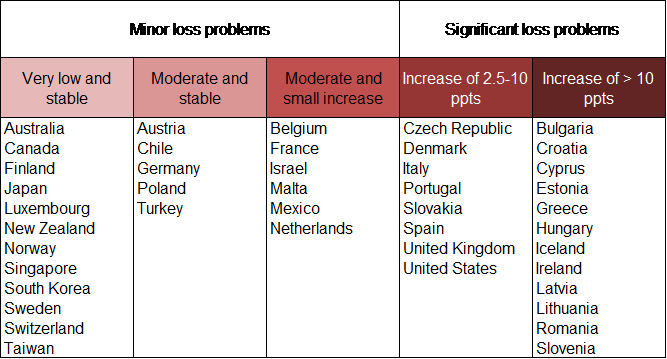

The table below classifies countries based on data on banks’ non-performing loans (NPL) from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. The 20 countries that had a substantial increase in the stock of domestic NPLs after 2007 (the final two columns), are treated as having experienced a domestic financial crisis.

Non-performing loans since 2007

Source: World Bank.

Note:

Very low and stable: NPLs: less than 2.5 percent of loans throughout, remaining at a stable percent of loans

Moderate and stable: NPLs: 2.5 to 5.2 percent of loans throughout, remaining at a stable percent of loans

Moderate and small increase: : NPLs greater than 2.5 percent of loans throughout, increasing by less than 2.5 percentage points

Mostly, the classification looks intuitive, and much as expected. All advanced countries that had a support programme with the IMF during that period are in the financial crisis category. At the other end of the spectrum, the commodity-exporting advanced countries (including New Zealand) all avoided a domestic financial crisis on this, as well as other, measures.

Two points may be worth noting. First, although the extreme liquidity crisis in the United States in 2008/09 attracted headlines – and had global ramifications – loan losses in the United States have been overshadowed by those in many European economies. One element of this is that more loans in the United States were not on the books of banks (and this is bank data). Second, although some banks in countries such as Germany and Switzerland got into material difficulties, in most cases those were the result of losses incurred in the United States. As discussed earlier, these losses probably had different implications for the performance of the home (German or Swiss) economy than losses arising out of domestic lending business.

If this classification looks broadly sensible, it is somewhat ad hoc, and might not easily generalise to other crises and other times, even if broadly comparable data were available for earlier periods.

One can’t just jump from this classification to the chart of GDP per capita performance to see whether countries that had financial crises, on this measure, did worse than those that did not. Apart from the many other influences on any country’s performance, it is also important to recognise that any causation can run in both directions. The argument that a quite-unexpected period of very weak economic performance will have generated large loan losses (many projects will have been based on assumptions that, however apparently reasonable, did not play out as expected) is at least as strong (I’d argue stronger) than the proposition that “financial crises” themselves cause sustained economic underperformance. Loan losses did not cause Greece’s problems, but were an integral of an overall process of economic mismanagement and misallocation of resources that led to Greece’s disastrous underperformance in recent years.

And what of New Zealand? We have had pretty low banking system NPLs throughout. Finance company losses mattered a lot to investors in those companies, but were still quite modest relative to the overall stock of loans in New Zealand. There were fiscal costs, through the deposit guarantee scheme, but without the international rush to guarantee schemes there would have been much the same loan losses and probably no direct fiscal costs.

As no major institutions failed, and (economywide) there was little evidence of sustained over-investment in any particular class of asset, one would not generally think of New Zealand having experienced a domestic financial crisis. Funding was disrupted for a time in late 2008/09, and that was among the factors inducing a greater degree of caution among lenders, but 6-7 years on it seems unlikely that any domestic financial stresses have materially affected New Zealand’s overall performance. For some sub-sectors, the picture might have been a little different, as finance companies had been major financiers for property developments, but for the economy as a whole the effect seems likely to have been quite peripheral. And yet, our economic performance has been similar to that of the United States, the epicentre of the initial crisis, and where the increase in actual loan losses was substantial.