The Herald’s editorial today is headed “Population growth is powering NZ economy”. It isn’t just a statement of the rather obvious, that a rapid growth in the population – particularly unexpectedly rapid growth – boosts total GDP. When there are more people, they all need to consume stuff, and they need houses, schools, shops, roads, offices etc. And unexpected surges in the population boost demand more, in the short-term, than they do supply. But they don’t do anything much to boost sustainable per capita real GDP.

That isn’t, of course, the Herald line. Rather, channelling the Prime Minister, they assert that

The population increase is helping to generate the growth in the economy that puts New Zealand ahead of most other and larger economies at present, which in turn makes it a magnet for yet more migrants, as well as persuading more young New Zealanders to stay here.

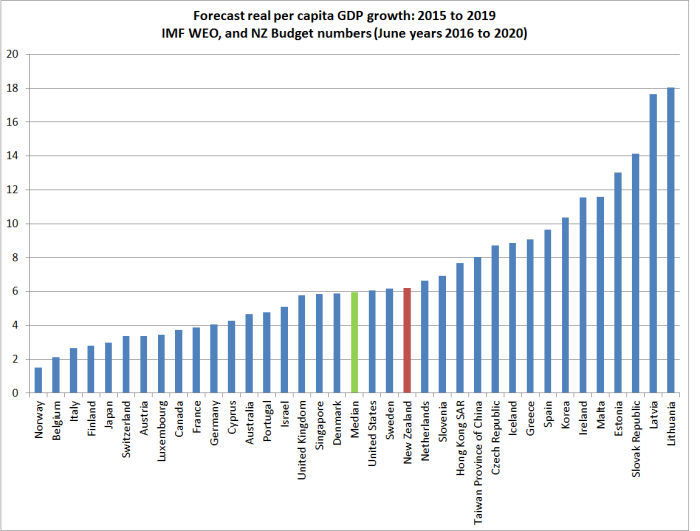

There is so much wrong with this sentence, it is difficult to know where to start. First, and repeating it slowly yet again, it is per capita economic growth that matters. New Zealand has been doing quite badly on that score over the last year or so, even by comparison with other countries. And as I illustrated yesterday, even on the Treasury’s own, optimistic-looking, numbers, we are expected to be only an average performer over the next four year. Average isn’t necessarily bad, except that we are starting out so much poorer than most advanced countries, and not closing the gap.

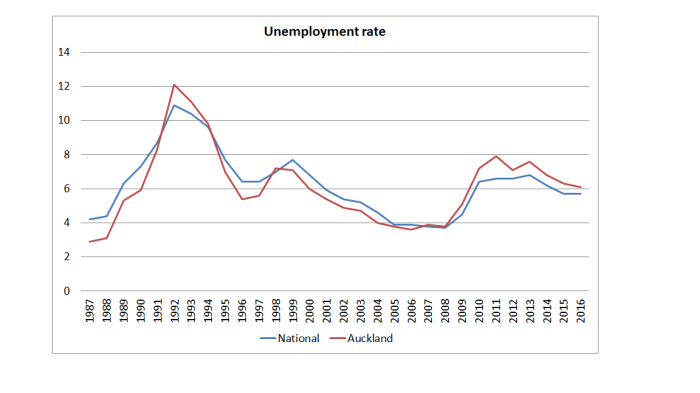

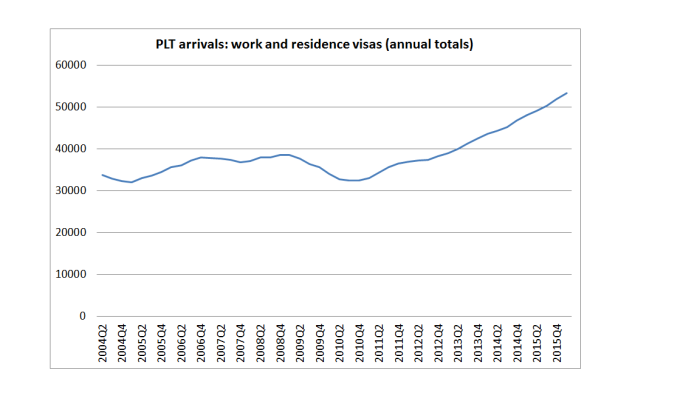

And it isn’t as if jobs are abundant here either, Our unemployment rate, at 5.7 per cent, is well above most estimates of the “natural” rate of unemployment, and not much below the median unemployment rate for OECD countries. The number of residence approvals here is subject to a target, so even if there is increased demand from foreign citizens to move here, it only increases slightly the quality of the people we can take, not the total number. Much of the variation results from two things. The first is the inflow of students, probably influenced more by the policy change allowing most to work here while they study, rather than by the intrinsic strength of the New Zealand economy. And the second is the flow – mostly of New Zealand citizens – to and from Australia. Australia’s unemployment rate is also now quite high, at 5.7 per cent, and New Zealanders moving there don’t have access to the welfare safety net and associated entitlements they do at home.

The editorial goes on

The Government would not want to say this out loud, but clearly it is not controlling immigration as tightly as previous governments have done. This attitude undoubtedly comes from the Prime Minister and it is consistent with his disinclination to restrict foreign investment or even monitor its impact on the house market. He deeply believes the country is better off being open and connected to the world’s flows of capital, trade and people. The performance of the economy on his watch suggests he is right. Even the housing affordability is a cost of prosperity. If we want drastic steps taken to stop rising prices we need to be careful what we wish for.

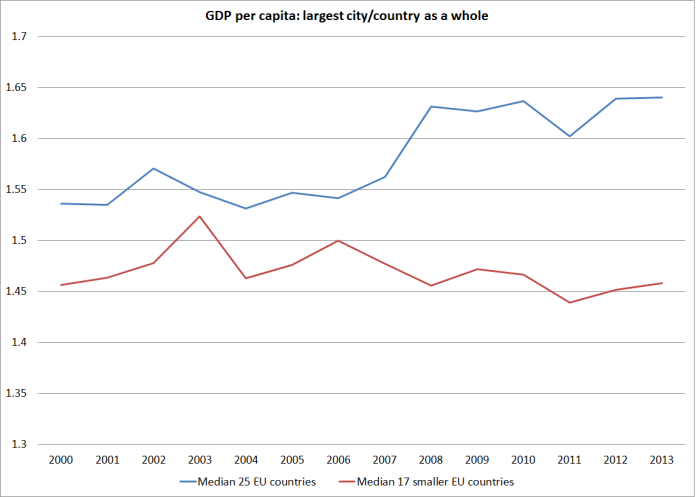

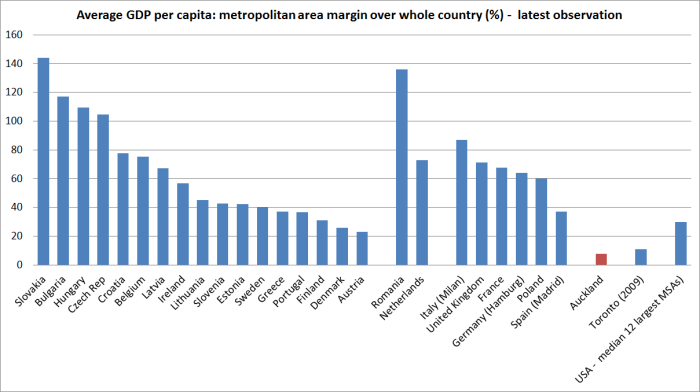

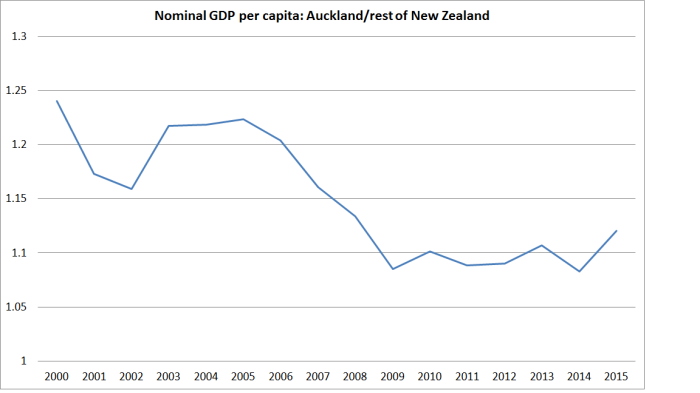

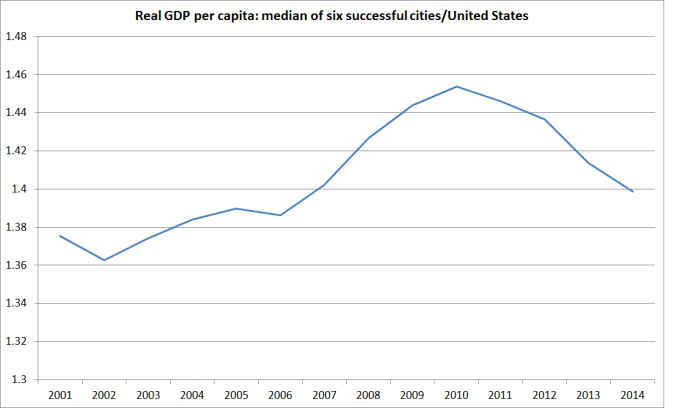

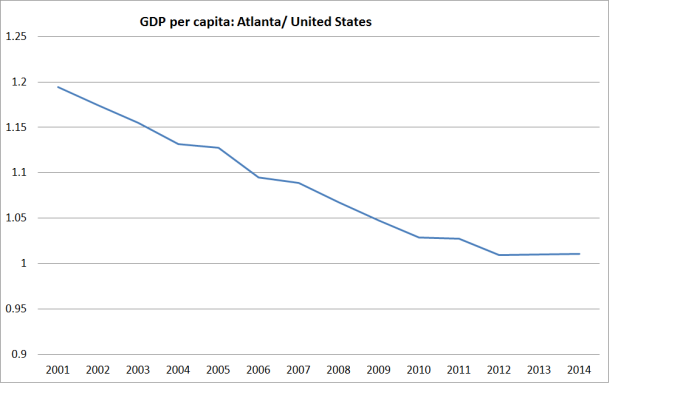

With the exception of allowing students to work, the initial claim here is simply incorrect. The residence approvals target is the same as it was under the previous government, and even student arrivals have not reached the peaks seen under the previous government. As for the rest, no doubt it accurately reports the Prime Minister’s views – he has repeated them often enough – but there is no evidence to support it. Productivity growth – the foundation of sustained long-term prosperity – has remained disappointingly weak. And the immigration inflows have been overwhelmingly concentrated in Auckland, and yet the official data show that Auckland incomes are (a) lower relative to those in the rest of the country than we see in most advanced countries (comparing dominant cities and the rest of the country) and (b) that that gap has been narrowing. Whatever the reason, the strategy is failing.

From there the editorial launches off into its own alternative universe

New Zealand’s desirable population size has always been a contentious subject, though not previously an urgent question. The increase since the turn of the century followed 25 years of static population figures as more people left than arrived.

Immigration policy was a notoriously capricious. Each time the economy dipped, governments would close the door. Now that we appear to have a rapidly growing population again, we need to be discussing how high we want it to go, and how it might be channelled to regions that most need it, and the houses and services it is going to need.

This country would benefit from many more people, and better preparation for their arrival.

There was a period from the mid 1970s to the late 1980s when New Zealand’s population growth was quite subdued. But for the last 25 years – not just since the turn of the century – we have had one of the faster population growth rates of the OECD. One doesn’t have to take a view on causation to note that people haven’t exactly been flocking to an economic success story. Incomes here are presumably better than they were in the migrants’ home countries, but our productivity growth rate over that 25 years has been among the very slowest in the OECD. Starting low, we’ve just drifted somewhat further behind.

I’m also not sure where the author gets the idea that New Zealand “immigration policy was notoriously capricious”. Yes, there are constant changes at the margin, but to a large extent we’ve been running much the same immigration policy for 25 years now, through several recessions, and some pretty sharp ups and downs in the labour market. Much the same could be said of the post-war decades, until the Labour government in 1974 closed down automatic access for British and Irish citizens – and that wasn’t because the economy was doing badly, but just because they thought immigration should be less focused on traditional sources countries.

Of course, I thoroughly agree that we should be having a national debate about immigration policy. Policy has long been premised, explicitly or otherwise, on the belief that New Zealand would be better, and more productive, if only there were more people. But there is just no evidence for that proposition, and certainly not enough on which to rest such a large scale economic and social intervention as our immigration policy. Big countries don’t grow faster than small ones. When we had 1 million people, there were calls for many more people. And when we had 2 million people. And when we had 3 million people. And so on. And for decades our relative incomes and productivity performance have been deteriorating. New Zealanders have been getting poorer relative to their advanced country peers. I’m not sure where the advocates think the critical threshold is where things might turn around – but clearly 4.5 million people hasn’t been enough either.

The editorial writer talks of channeling people to “the regions”, which is almost certainly even more wrongheaded than bringing in large numbers in the first place. We’ve seen that in the policy changes the government made last year: giving more points to people with job offers from the regions simply has the effect of lowering the average quality of the migrants we do get, who (on average) have not been terribly highly-skilled in the first place.

Instead of constantly championing the case for ever more people – even at the cost of encouraging New Zealanders to leave Auckland (a weird way to help people at the bottom) – it is about time there was a serious conversation that stopped pretending everything was fine, and confronted the facts of New Zealand’s economic underperformance, and Auckland’s economic underperformance. Doing so would force people to think harder about whether there was much realistic prospect of New Zealanders benefiting from an ever-increasing migration-fuelled population. I’m not suggesting a population policy – fertility and emigration choices of New Zealanders are their own affair – rather, the abandonment of the implicit “big New Zealand” population policy we have had through successive governments. Pretty much everyone accepts (and it is an uncontested OECD empirical result) that our distance from markets (and competitors) is a material penalty, making it harder to generate really high per capita incomes in New Zealand. There is still no sign that New Zealand is getting much traction in products and markets that don’t rely largely on our natural resources – and utilizing those natural resources in ever smarter ways simply does not need lots more people. Why penalize everyone more by rapidly increasing the population of a country with such a disadvantageous location?

The Herald is right that without the unexpected surge in immigration total GDP today would be lower than it is. But without the surge in immigration over the last few years then, all else equal, our interest rates would also be lower, and our exchange rate would be lower. And New Zealanders as a whole would be better off, because more firms would be better positioned to sell products and services into world markets at competitive prices. But, probably more importantly in the long-run, our largely fixed stock of natural resources, found on not-very-propitiously-located remote islands, would be spread over rather fewer people. As a country we’d be better off, and lower Auckland house prices – no doubt still distorted by unnecessary land use restrictions – would be a beneficial mark of that success. As it happens, the regions – where the natural resources mostly are (pasture, forests, mines, seas, landscapes) – would loom larger relative to Auckland, curiously the goal that the Herald’s editorialist seems to espouse.

And it isn’t just that Christchurch has had a very low unemployment rate through the repair and rebuild period. Graphing the Auckland unemployment rate against that of the median region produces much the same picture.

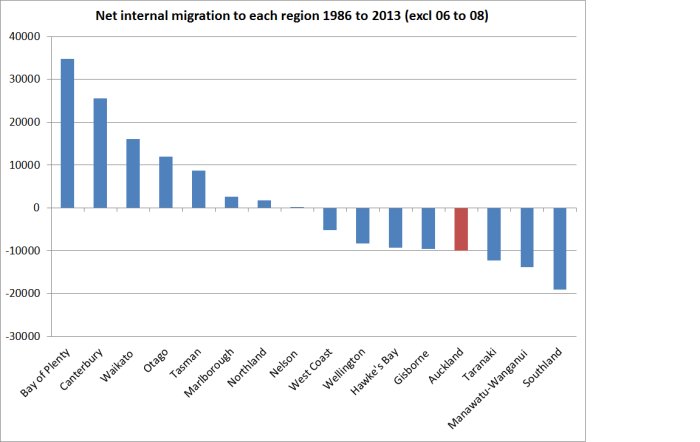

And it isn’t just that Christchurch has had a very low unemployment rate through the repair and rebuild period. Graphing the Auckland unemployment rate against that of the median region produces much the same picture. And the massive increase in student visa numbers (mostly to second tier non-university entities), many of whom later acquire residence, is on top of that.

And the massive increase in student visa numbers (mostly to second tier non-university entities), many of whom later acquire residence, is on top of that. Net, a small number of New Zealanders left Auckland for other parts of the country. Relative to Auckland’s population, the estimated outflow is tiny, but there is just no sign of New Zealanders flocking to the “success” of Auckland (and note that this period includes the outflow of people from Christchurch in couple of years after the earthquakes). Perhaps things have been different in the last three years, for which we don’t yet have data.

Net, a small number of New Zealanders left Auckland for other parts of the country. Relative to Auckland’s population, the estimated outflow is tiny, but there is just no sign of New Zealanders flocking to the “success” of Auckland (and note that this period includes the outflow of people from Christchurch in couple of years after the earthquakes). Perhaps things have been different in the last three years, for which we don’t yet have data.