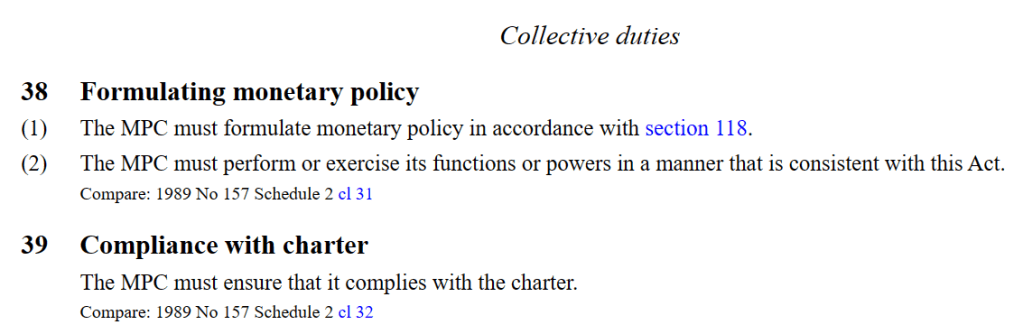

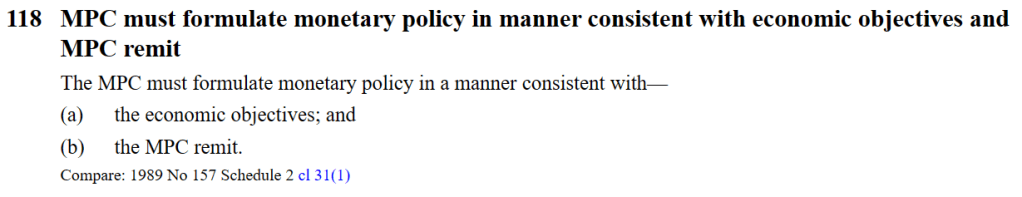

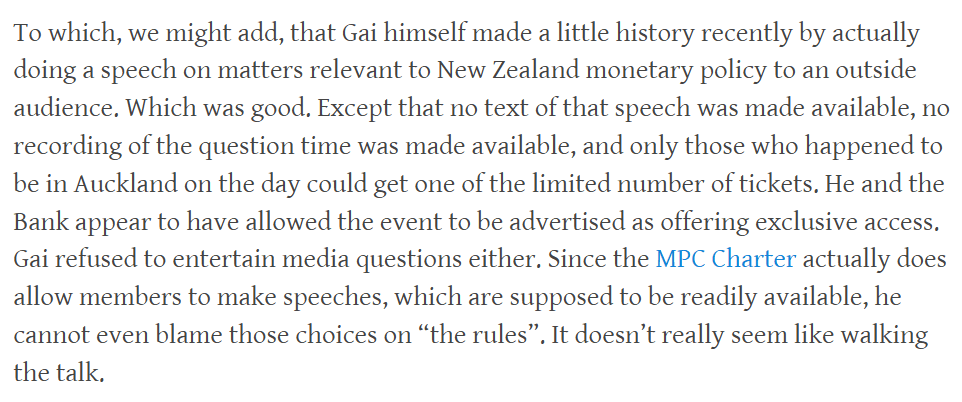

For the first six years of the newly-created statutory Monetary Policy Committee the external members were conspicuous by their silence. While their charter (agreed with the Minister of Finance) allowed them to speak openly we heard almost nothing from any of the three of them (and of course no disclosure of views or thinking in the minutes of the MPC either). The contrast with models like the central banks in the United States, Sweden, and the UK was stark.

This year there has been some sign of progress, albeit only from one of the members (whose approach may not be terribly popular with his MPC colleagues or – though they have very limited say – the Reserve Bank Board). The member in question is Prasanna Gai, a professor of macroeconomics at the University of Auckland and someone who spent the early part of his career at the Bank of England (and has had various other central banking involvements since). On paper he appears by far the strongest of the externals (and probably more so that at least of the internals), even if there is something less than ideal about having someone serving at the same time as an MPC member and on the board of the Financial Markets Authority. We also know nothing directly about his view on the state of the economy or much about his thinking about policy reaction functions etc, although we can deduce from his two recent speeches that he is probably the key player in the rather heavy (over)emphasis on uncertainty from the MPC in the last six months.

I wrote a few months ago about Gai’s published views (to be clear, from before he became an MPC member) on how Monetary Policy Committees should be functioned and governed. That post was shortly after his first speech

But in the last few weeks there have been two more sets of (fairly brief) remarks, and things have improved somewhat. In their email notification of upcoming speaking engagements, Bank management has noted that the two events were coming up, and the texts of the two sets of remarks are on the website (although you get the impression the Bank might be unenthused because they have not emailed out links, leaving people to remember to go and look for them, or otherwise to stumble over them).

The first of those sets of remarks was about uncertainty (mostly in the light of the US tariff situation), delivered to (it appears) an academic audience in Melbourne a few weeks ago. In those remarks, which were expressed reasonably abstractly, Gai could most reasonably be read as suggesting that the trade policy uncertainty was having a material macroeconomic effect on New Zealand and that fairly bold monetary policy responses were appropriate. I put some comments about those remarks on Twitter, which are in a single document here

tweet thread on Prasanna Gai’s uncertainty remarks

While welcoming the fact of the speech, I was a bit sceptical of the argument. But then the good thing about policymakers laying out their thinking is so we can scrutinise, challenge, and engage with those arguments.

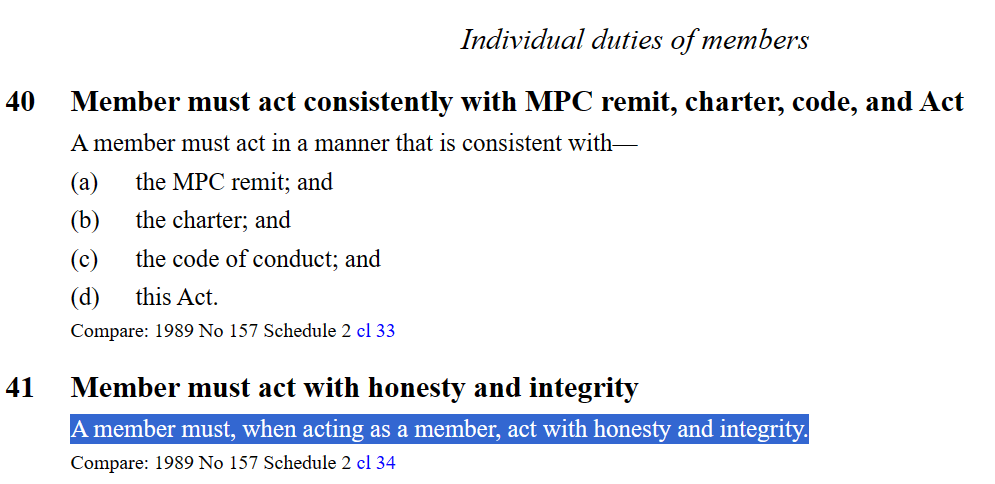

Gai’s most recent set of remarks was to some forum run by the Ministry for Ethnic Communities (one of those entities whose continued existence casts severe doubts on government rhetoric about cost-savings and lean efficient bureaucracy – but that isn’t Gai’s fault). There is more about uncertainty (in fact the remarks carry the title “Navigating the Fog – A Tryst with Economic Uncertainty”) although he takes the issue rather wider than the US tariffs stuff. I still wasn’t entirely persuaded, especially by the sentence I’ve highlighted.

Faced with the unknown, and already in the midst of a downturn, economic actors hesitate, delay investments, and reduce engagement. We see this in NZ surveys like the QSBO. Paradoxically, this cautious behaviour, while individually sensible, creates a self-fulfilling cycle. Caution reduces economic activity, which deepens uncertainty, leading to even more caution. Economists call this the “uncertainty trap.” It locks the economy into stagnation. By avoiding risk, we inadvertently create the very uncertainty we seek to avoid. This cycle of inaction feeds into a broader macroeconomic malaise, where growth stagnates, prices become sticky, opportunities are missed, and innovation slows. When everyone waits, nothing moves.

No doubt we can all agree in wishing away a fair amount of avoidable uncertainty (probably most people in New Zealand would count the US tariff uncertainty – regime uncertainty from day to day – in that category) but uncertainty is a part of life and always been. Perhaps it is greater in the short to medium term in democracies and market economies (absolute dictators can, although perhaps rarely do, provide greater certainty about some things over those horizons) so it seems a bit odd to suggest that people dealing with uncertainty is somehow problematic, or even creates uncertainty itself. There is more stuff along these lines in the remarks.

But my main interest in this set of remarks was the section headed “What Can Policymakers Do?”. He seems to think they can and should do a lot. I suspect he is far too ambitious (including on fiscal policy where he observes “At the same time, fiscal policy must step into its own strategic role — by investing through uncertainty and setting the stage for deep microeconomic reform. Where private actors

hesitate, public action creates space — catalysing investment in innovation, skills,

infrastructure, and housing8. And, like monetary institutions, fiscal policy must be guided

by intellectual clarity, coherence, and long-term commitment.”)

But again, my main interest is monetary policy. He writes

In other words, central banks must set the tone for the economic conversation. Their words, emphasis, and structure condition how millions of decisions unfold. They must illuminate the path ahead, not merely comment on the prosaic.

Transparency – describing the macro-landscape by publishing monetary policy statements and modelling scenarios – is helpful, but not enough. What really matters is the capacity to guide expectations. This requires intellectual rigour, deep technical expertise, and the agility to challenge conventional thinking. How we think, rather than who said what, is the essence of credibility when uncertainty is high.

It is important to remember that central bankers wield unelected power7. Direct engagement—through public speeches and testimony before Parliament—brings clarity to uncertainty. Speaking directly about how we think, and what would change our minds, provides analytical accountability that complements procedural channels that chronicle debate – such as meeting records and monetary policy statements. When we open the doors of our policy reasoning to scrutiny, the fog clears and trust builds.

There is good stuff there (and in that footnote 7, which I’ve not reproduced, he refers readers back to the paper he wrote pre-appointment (see above), observing “some of those lessons are relevant for New Zealand”).

He is clearly laying down a marker here advocating for a materially greater degree of transparency from the New Zealand Monetary Policy Committee. The incoming Governor – about whom I will probably write later this week – went on record at her appointment announcement as favouring greater monetary policy transparency (unsurprisingly given that the Swedish central bank has substantively the most transparent monetary policy decision-making etc model anywhere). But you have to suspect it is going to be an uphill battle in an institution with a deeply rooted culture (not specific to any particular Governor) of favouring transparency only when it suits, whereas real transparency and accountability are about openness even when it hurts).

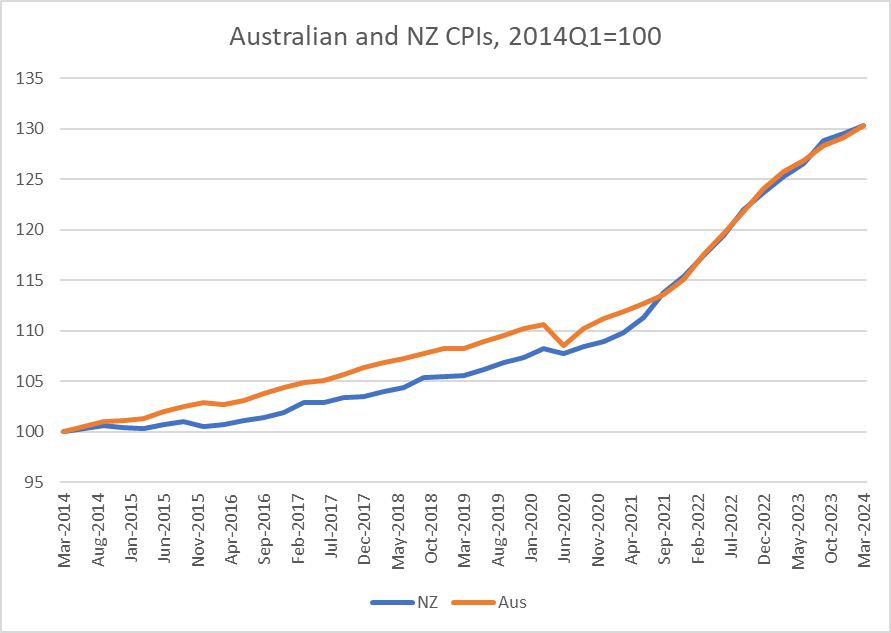

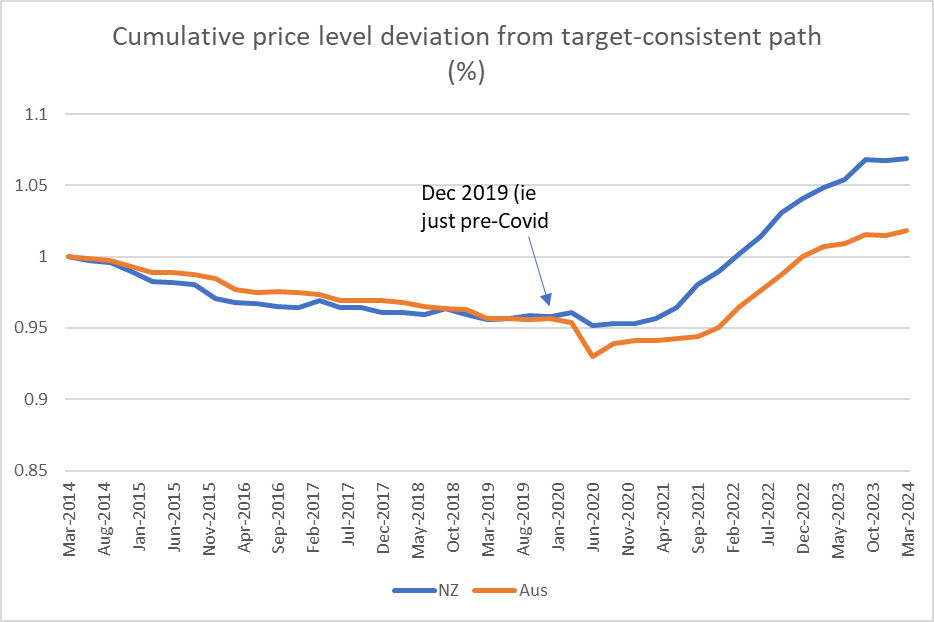

I’m all in favour of much greater transparency (and the new Bank of England MPC model looks as though it could provide a good model). But there is an important distinction between transparency that makes a difference to macroeconomic outcomes and that which largely supports heightened accountability. Perhaps the two should overlap but they rarely do. It isn’t obvious, for example, that the central banks that are much more open, including about differences of views and models among members, or whose MPCs had deeper stores of technical expertise among their membership, did any better at all – in terms of inflation outcomes – through the dreadful inflation resurgence of the early 2020s than, say, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s MPC did. But in those countries with greater transparency we know a lot more about the views of individual members and their thought processes and are thus better positioned to assess whether perhaps some are less guilty than others. Individual accountability is, thus, a serious possibility.

My impression is that Gai is much more optimistic about the scope for enhanced transparency to make a macro difference. In a sentence before the block of text I quoted he says “when uncertainty is high and the channels of transmission are weak, communication takes on greater importance”.

Well, perhaps, but only if the central bank has something meaningful to say, otherwise it just ends up as cheap talk. No doubt we can all agree that central banks should always and everywhere indicate that if (core) inflation looks like going off course they will respond accordingly. That is a (much) better place than we (advanced world fairly generally) were in 50 years ago, but it isn’t really much help in grappling the high levels of uncertainty firms and households actually face at times, most of which isn’t about monetary policy. Central banks can’t add much of any use on where US trade policy may go, let alone how other countries might or might not respond. Or whether (let alone when) the AI stock market surge will prove to be a bubble that will burst nastily. Or whether China will invade Taiwan. Or, to be more pointed and winding the clock back five years, what would happen to policy regimes around Covid (lockdowns, border closures etc) – surely the most extreme, perhaps inescapable, example of policy uncertainty in recent times. Central banks generally couldn’t get the macroeconomics right even when the policy uncertainty began to diminish (see inflation outcomes and generally very sluggish interest rate responses). The ability to “illuminate the path ahead, not merely comment on the prosaic” seems very limited in practice in most circumstances. (I think back, for example, to the early days of inflation targeting in New Zealand: we aimed then to be very transparent, and had a Governor who was a strong retail communicator, and yet if we consistently held out a vision – sustained low inflation and a fully-employed economy – we had no certainty to offer as to what it would take or when the payoff would be seen. Bigger central banks that went through similar dramatic disinflations generally found themselves in the same boat.)

But to conclude, it is great to have an MPC member putting his thinking on record (even in this case it is still mostly about processes/structures than the specifics of how the economy and inflation might unfold). Perhaps some journalists might ask him about the speech and seek to tease out his ideas. We all benefit when those wielding power – unelected power in this case as he rightly notes – put their ideas out for information, scrutiny, and debate. Perhaps some other MPC members might think of taking up speaking opportunities that come. Perhaps Gai, who has dipped his toe in the water with a couple of brief sets of published remarks, might consider a fuller version at some point?