I’m sitting here a bit puzzled at what approach to contesting or debating policy they now teach and model at Oxford University, or practice at Auckland University of Technology.

A few weeks ago, I posted here a submission I’d made to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into how New Zealand might make a transition to a low-emissions economy, and arguing that immigration policy should at least be considered by the Commission as one material influence on total New Zealand emissions, and as a potential tool to facilitate a cost-effective pursuit of the goverment’s emissions target. Late last week, Newsroom published a column of mine based on that submission. In that column I noted that

New Zealand has committed to a fairly ambitious emissions reduction target as part of the Paris climate agreement. Of course, some political parties think the target isn’t ambitious enough, but New Zealand faces an unusual set of factors that affect our ability to reduce emissions here at moderate cost. Appropriate policy responses, and the choice of the mix of instruments we choose to deploy, need to take account of that distinctive mix.

and concluded

The aim of a successful adjustment to a low-emissions economy is not to don a hair shirt and “feel the pain”. It isn’t to signal our virtue either. Rather, the aim should be to make the adjustment with as small a net economic cost to New Zealanders – as small a drain on our future material living standards – as possible. Lowering the immigration target looks like an instrument that needs to be seriously considered – including by the Productivity Commission – if that goal is to be successfully pursued.

The backdrop of course – and a point made in both the submission and my column – was the arguments I have been running for some years now suggesting that immigration policy itself been damaging to our economic performance, and thus has come at some net economic cost to New Zealanders.

But one academic reader decided that rather than engage primarily on the substance of the arguments I’d made – the bottom line of which, after all, was simply that the Productivity Commission shouldn’t just ignore the issue – he’d try to muddy the waters with some slurs.

David Hall is a young academic researcher at AUT, having returned to New Zealand relatively recently after doing a D. Phil at Oxford. While he was in the UK he, for a time, had a regular Listener column. His academic background appears to be in politics rather than economics, but he has been writing about climate change policy and was the editor of the recently-published BWB Texts book Fair Borders? Migration Policy in the Twenty-First Century, a collection primarily about aspects of New Zealand’s approach to and experience of immigration. I’ve written previously about a couple of chapters in the book (here and here). As I noted in the latter of those posts

As much as I can, I try to read and engage with material that is supportive of New Zealand’s unusually open immigration policy. One should learn by doing so, and in any case there is nothing gained by responding to straw men, or the weakest arguments people on the other side are making.

Newsroom has published a response by Hall to my column (they even illustrated it with a photo of my own suburb, Island Bay). There are some points of substance in Hall’s response, and I want to come back to them in a separate post.

But it was these two paragraphs that really annoyed me

What’s striking about all this is not only Reddell’s argument is from the perspective of climate change, but also economics. He resists the orthodox view that migration has a modest positive impact on national GDP. I’m no enemy of disciplinary iconoclasm, but it does beg for robust positive arguments. Reddell’s appeals to uncertainty (economists cannot prove definitively that migration increases GDP, therefore it might not be true) do not count. Climate scientists are all too familiar with this kind of denial.

So if economic evidence cannot always carry his arguments, one can only conclude that non-economic reasons are doing some of the work. To Reddell’s credit, he is explicit about his concerns for cultural cohesion, or that “Islam is a threat to the West, and a threat to the church wherever it is found”. These are real reasons for wanting to reduce immigration, but should be debated on their ethical and sociological merits, not couched in an idiosyncratic take on climate policy.

This is frankly pretty scurrilous stuff.

Apparently, when it comes to the economics of immigration, all I’m doing is “appealing to uncertainty” not advancing any “robust positive arguments”. This is, so he claims, the economics equivalent of “climate change denial”.

First, lets look at what I’d actually said in my column

Of course, if there were clear and material economic benefits to New Zealanders from the high target rate of non-citizen immigration (the centrepiece of which is the 45,000 per annum residence approvals “target”) it might well be cheaper (less costly to New Zealanders) to cut emissions in other ways, using other instruments. But those sort of gains – lifts in productivity – can’t simply be taken for granted in New Zealand. Despite claims from various lobby groups that the economic gains (to natives) of immigration are clear in the economics literature, little empirical research specific to New Zealand has been undertaken. And there is good reason – notably our remoteness – to leave open the possibility that any gains from immigration may be much smaller here than they might be in, say, a country closer to the global centres of economic activity, whether in Europe, Asia, or North America.

Even many of those who are broadly supportive of New Zealand’s past approach to immigration policy will now generally acknowledge that any gains to New Zealanders may be quite small. And for some years now, I’ve been arguing for a more far-reaching interpretation of modern New Zealand economic history: that our persistently high rates of (non-citizen) immigration have held back our productivity performance (i.e. come at a net economic cost to New Zealanders).

It isn’t controversial to suggest that there has been little empirical research specific to New Zealand on the contribution of immigration policy to New Zealand’s economic performance. It is simply an accepted fact – and the chair of the strongly pro-immigration New Zealand Initiative accepted as much in an exchange here last year. I also don’t think it is controversial to suggest that any economic gains to New Zealanders may be quite small – it was, as I recall, the conclusion of Hayden Glass and Julie Fry (both generally pro-immigration) in their BWB Texts book last year. Remoteness is generally accepted as an issue in New Zealand’s economic performance – even if reasonable people differ on the implications and appropriate policy responses.

And then there was the reference to “and for some years now I’ve been arguing”. Since the point of the emissions/immigration column was to argue that the connection should be considered, not to attempt to demonstrate that immigration has been economically costly, I didn’t elaborate in that column. But it would, to most readers, have been a hint that there was a bit more to the argument than “appealing to uncertainty”. If Hall himself hadn’t been familiar with my arguments, Google would willingly have helped. There are, I see, 140 posts on this blog tagged with “immigration”, and there are plenty of speeches and papers, and a lengthy commentary on the New Zealand Initiative’s major piece earlier this year making the case for New Zealand’s immigration policy. Only last week, in a post where I outlined some specific alternative immigration policy proposals, I linked to a recent speech outlining the economic case – specific to New Zealand – for rather lower target rates of non-citizen immigration. People might disagree with my economic arguments and reading of New Zealand’s economic history, but none of those arguments is a mystery to anyone interested.

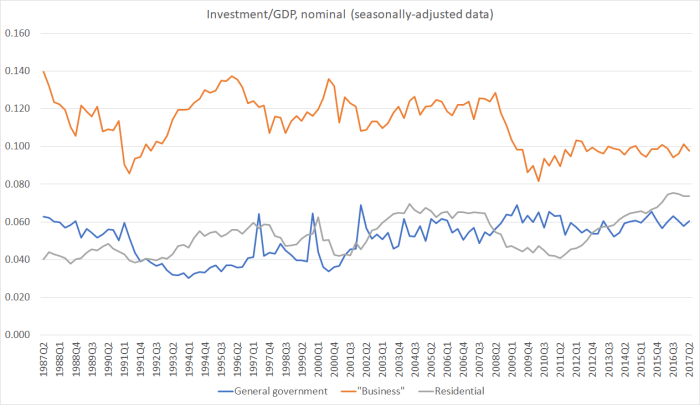

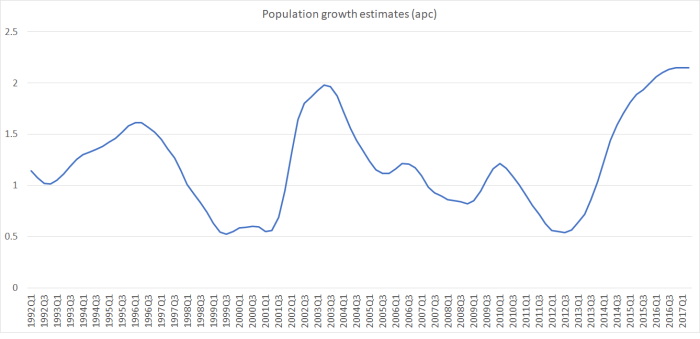

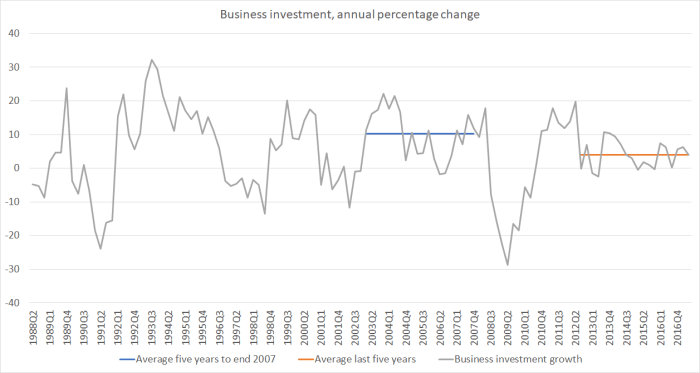

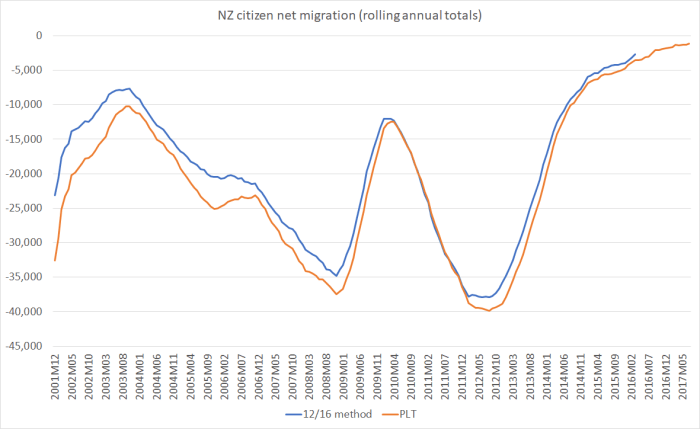

(In – very – short, (a) extreme remoteness makes if very difficult to build many high productivity businesses here that aren’t natural resource based, and (b) in a country with modest savings rates, rapid population growth has resulted in a combination of high real interest rates and a high real exchange rate, discouraging business investment and particularly that in the tradables – internationally competitive – sectors, on which small successful economies typically depend. I add to the mix how unusually large our immigration target is and how, despite the official rhetoric, the skill levels of the average and marginal migrants are not particularly high.)

But Hall’s rhetorical strategy rests on making as if none of this extensive body of argumentation and analysis exists, that I’m playing distraction, and then falling back on the “Muslim card”.

In parallel to this blog, I maintain a little-read (and these days, little written) blog where I occasionally write on matters of religious faith and practice, and sometimes on a Christian perspective on public policy issues. If there is a target audience it is fellow Christians and in writing there I take for granted the authority of the Bible, and of church teaching and tradition over 2000 years. I very rarely link to it here, as there is typically little overlap in subject matter and I know that most of the readers of this blog don’t share those presuppositions.

A couple of years ago, I wrote a couple of posts about refugee policy, prompted by some domestic commentary on the possible economic case for taking more refugees (in particular from Syria). On this blog, I wrote something fairly short and narrowly focused on the economics, noting that there were unlikely to be net economic benefits to New Zealanders. I concluded that

None of which is an argument for not taking refugees. Doing so is mainly a humanitarian choice, not something we do because we benefit from doing so. I don’t have a strong view on how many refugees New Zealand should take, but I don’t think possible economic benefits to us should be a factor one way or the other.

We do good because it is right to do so, not for what it might do for us. Whether “doing good” in this case involves taking more refugees, or donating more money to cost-effectively assist in refugee support in the region, is a more open question.

A day or so later I wrote a longer post on my Christian blog on the refugee issue through the lens of the gospel, and included a link to that post at the end of the “economics of refugees” post. At the end of quite a long post, aimed at Christian readers (and none of which I would resile from now) I included the phrase Hall now seeks to highlight. Here is the full text

Islam is a threat to the West, and a threat to the church wherever it is found. Political authorities in the West were right, and well-advised, to resist in the past, and at the Battle of Tours, at Lepanto, and at the gates of Vienna, to begin to turn the tide. We owe it to the next generations of our own people to resist the creeping inroads of Islam. If New Zealanders convert to that faith, there is of course little we can do, but neither compassion nor common sense requires, or suggests it would be prudent, for Western countries with any sense of their own identity to take in large numbers of Syrian refugees or migrants.

Frankly, I was a bit puzzled as to how Hall – an apparently secular academic – was aware of this obscure post, with perhaps 100 readers in total, but not of the substance of my economic arguments. But in an email exchange overnight, he tells me that he is actually familiar with this blog, and presumably with its economic arguments, and found the Christian post on refugees through this blog. At least that answered that question, even if it doesn’t explain his attempt to pretend that I’m not raising substantive, or developed, economic arguments.

And as he acknowledges that he is familiar with this blog, perhaps he might have considered looking at the material I’ve posted here on the issues around culture, diversity etc. There was, for example, this address to a Goethe Institute event on diversity etc. Or a post earlier this year where I explicitly laid out some thoughts on culture and identity issues in response to one chapter of the New Zealand Initiative’s report.

I began the post by making the point I often use

My focus has tended to be on economic issues – and thus to be largely indifferent on that count whether the migrants came from Brighton, Bangalore, Beijing, Brisbane or Bogota. Almost all of my concerns about the economic impact of New Zealand’s immigration programme would remain equally valid if all, or almost all, our immigrants were coming from the United Kingdom – as was the case for many decades.

Nonetheless, I noted that there were many groups of people who I would not have welcomed large number of migrants from

So long as we vote our culture out of existence the Initiative apparently has no problem. Process appears to trump substance. For me, I wouldn’t have wanted a million Afrikaners in the 1980s, even if they were only going to vote for an apartheid system, not breaking the law to do so. I wouldn’t have wanted a million white US Southerners in the 1960s, even if they were only going to vote for an apartheid system, and not break the law to do so. And there are plenty of other obvious examples elsewhere – not necessarily about people bringing an agenda, but bringing a culture and a set of cultural preferences that are different than those that have prevailed here (not even necessarily antithetical, but perhaps orthogonal, or just not that well-aligned).

I went on, talking about the Initiative

They take too lightly what it means to maintain a stable democratic society, or even to preserve the interests and values of those who had already formed a commuity here. I don’t want stoning for adultery, even if it was adopted by democratic preference. And I don’t want a political system as flawed as Italy’s,even if evolved by law and practice. We have something very good in New Zealand, and we should nurture and cherish it. It mightn’t be – it isn’t – perfect, but it is ours, and has evolved through our own choices and beliefs. For me, as a Christian, I’m not even sure how hospitable the country/community any longer is to my sorts of beliefs – the prevalent “religion” here is now secularism, with all its beliefs and priorities and taboos – but we should deal with those challenges as New Zealanders – not having politicians and bureaucrats imposing their preferences on future population composition/structure.

But the New Zealand Initiative report seems to concerned about nothing much more than the risk of terrorism.

A commonly cited concern in the immigration debate is of extremism. The fear of importing extremism through the migration channel is not unreasonable. The bombing of the Brussels Airport in 2016, in which 32 people were killed, or the Bataclan theatre attack in Paris where 90 people were murdered, shows just how real the risk is.

The report devotes several pages to attempting to argue that (a) the risk is small in New Zealand because we do such a good job of integrating immigrants, and (b) that the immigration system isn’t very relevant to this risk anyway.

The point they simply never mention is that in many respects New Zealand has been fortunate. For all the huge number of migrants we’ve taken over the years, only a rather small proportion have been Muslim.

I went on

They highlight Germany – perhaps reflecting the Director’s background – where integration of Turkish migrants hasn’t worked particularly well over the decades, while barely mentioning the United Kingdom which is generally regarding as having done a much better job, and yet where middle class second generation terrorists and ISIS fighters have been a real and serious threat. Here is the Guardian’s report on comments just the other day from a leading UK official – the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation – that the UK now faces a level of threat not seen since the IRA in the 1970s. Four Lions was hilarious, but it only made sense in a context where the issue – the terror threat – is real.

But the Initiative argues that few terrorists are first generation immigrants, and some come on tourist or student visas (eg the 9/11 attackers) and so the immigration system isn’t to blame, or the source of a solution. I’d largely agree when it comes to tourists, and perhaps even to students – although why our government continues to pursue students from Saudi Arabia, at least one of whom subsequently went rogue having become apparently become radicalised in New Zealand, is another question. But there are no second generation people if there is no first generation immigration of people from countries/religions with backgrounds that create a possibility of that risk. Of course the numbers are small, and most people – Islamic or not – are horrified at the prospect of terrorism, or of their children taking their path. But no non-citizens have a right to settle in New Zealand, and we can reduce one risk – avoiding problems that even Australia faces – by continuing to avoid material Muslim migration.

Having said that, I remain unconvinced that terrorism is the biggest issue. Terrorists don’t pose a national security risk. Whatever their cause, they typically kill a modest number of people, in attacks that are shocking at the time, and devastating to those killed. But they simply don’t threaten the state – be it France, Belgium, Netherlands, the US, or Europe. Perhaps what they do is indirectly threaten our freedoms – the surveillance state has become ever more pervasive, even here in New Zealand, supposedly (and perhaps even practically) in our own interests.

The bigger issue is simply that people from different cultures don’t leave those cultures (and the embedded priors) behind when they move to another country – even if, in principle, they are moving because of what appeals about the new country. In small numbers, none of it matters much. Assimilation typically absorbs the new arrivals. In large numbers, from quite different cultures, it is something quite different. A million French people here might offer some good and some bad features. Same goes for a million Chinese or Filipinos. But the culture – the code of how things are done here, here they work here – is changed in the process.

So, Dr Hall, despite your attempts to suggest otherwise, basically none of my concerns about New Zealand’s immigration policy have anything to do with Islam at all. Very few of the huge number of migrants we’ve taken over the years have been from Muslim backgrounds. It simply isn’t an issue New Zealand has faced (unlike, say, Australia). As I’ve said previously, my economic arguments are blind to which country, or religious background, immigrants have come from. We’ve taken lots and lots of people, from wherever, and the numbers are – on my argument – the issue, not the origins. Those arguments apply as strongly to the post-war decades – when most of the immigration was from the UK – as they do in the last couple of decades. And – to revert to the emissions/immigration connection, all those migrants – wherever they’ve come from – have added to New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions.

(To be clear, I would be uneasy about large scale Muslim immigration, on non-economic grounds. But I’m quite sure I wouldn’t be alone in that – in an exchange on his blog earlier in the year, even strongly pro-immigration New Zealand Initiative Chief Economist Eric Crampton noted that his one area of concern might be migrants who would undermine our democratic norms. Eric seems to be quite strongly anti-Christian (and probably anti all religions) but he acknowledged that large numbers of Wahhabi Saudi immigrants – not in prospect – would be a serious concern.)

In reading some more of Hall’s own views on immigration, I found an interview with him in which he notes

But we also need to redistribute power and especially to give Maori greater influence over the ends and means of migration policy. I support Tahu and Arama’s call for tangata whenua to exercise greater influence on border policy as part of an emboldened tino rangatiratanga, not least because Māori have the most to lose from unfair migration.

I don’t agree with him on that, but my own thoughts on the implications of immigration policy for the Maori place in New Zealand are in the Goethe Institute piece linked to earlier and in a fairly-read post here earlier in the year, again prompted partly by the Initiative’s report. In it I raised, for a general audience, concerns perhaps not a million miles from some of his own.

But don’t try to pretend that (a) there are not serious economic questions to be answered about the impact of our large-scale immigration programme, or (b) that I have not posed them, almost ad nauseum. I’ll come back to some of the specifics around population and emissions targets, and the place of national policy in a wider world, in a separate post.