The strongly pro-immigration political and business establishment must have been very grateful to the proprietors of the Herald for making so much space available for lengthy unpaid advertorials for high – perhaps even higher – rates of immigration to New Zealand. They even provided a journalist to write these paeans.

First, there was a double-page spread in Friday’s newspaper and then yesterday there was a further gung-ho column (under the heading “New Zealand leading the way on immigration debate”), both by Liam Dann. When I saw yesterday’s column my first reaction was “yes, and the Pied Piper of Hamelin also found followers – much good it did them”.

The double-page spread on Friday purported to be journalism: Dann had gone out and talked to various people, but every single one of them seemed to be either keen on high rates of immigration to New Zealand or wanting even more (wanting rules changed to be even more employer-friendly). He even gave an uncritical platform for Statistics New Zealand, the agency which – unable to conduct a competent Census – has now delivered us permanent and long-term net migration data that is so bad (in the short-term) that even the Reserve Bank the other day indicated that they were now reduced to forecasting flows starting nine months prior to the publication date of their forecasts (whereas previously they had good indicative data available on a timely basis).

Much of the initial story seemed to be built around a premise that the parties in government had not delivered on promises to lower net migration. But then whenever he has been in government Winston Peters has never done anything material to make a difference to immigration numbers. There is no sign he has ever regarded the issue as particularly important. And, if you check out their 2017 manifesto they didn’t make such promises then either – there was, for example, no suggestion of cutting residence approvals numbers. Sure there was some loose talk of net migration numbers falling, but then official forecasts (eg those by the Treasury or the Reserve Bank) also had large cyclical falls projected back then.

What about Labour? Despite attempts to suggest otherwise, they did not promise to reduce the net migration inflow by 25000 to 30000 per annum. I wrote about their immigration policy proposals here, prior to the election. What Labour promised was a series of changes around study and temporary work visas which, if implemented, might have had the effect of reducing the net inflow by those sort of numbers, for one year only. Nothing Labour proposed would have affected residence approvals numbers at all, and thus nothing would have affected the projected net inflow over, say, a 5 to 10 year period.

Of course, none of this is to deny that both Labour (at least under Andrew Little) and New Zealand First might have been happy to try to create the impression that things would be materially different under them. But nothing they promised would ever have done so, and (unsurprisingly) nothing they have delivered has.

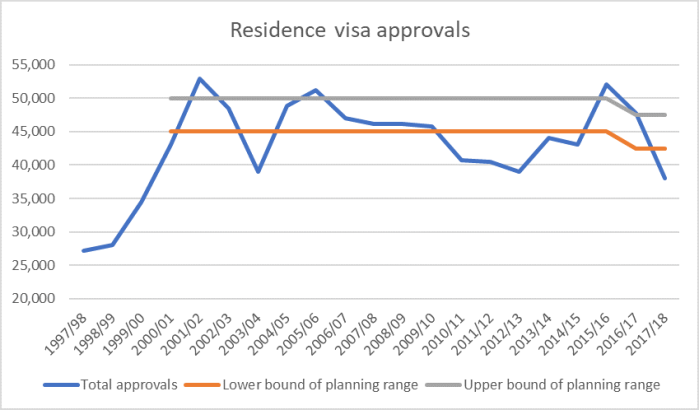

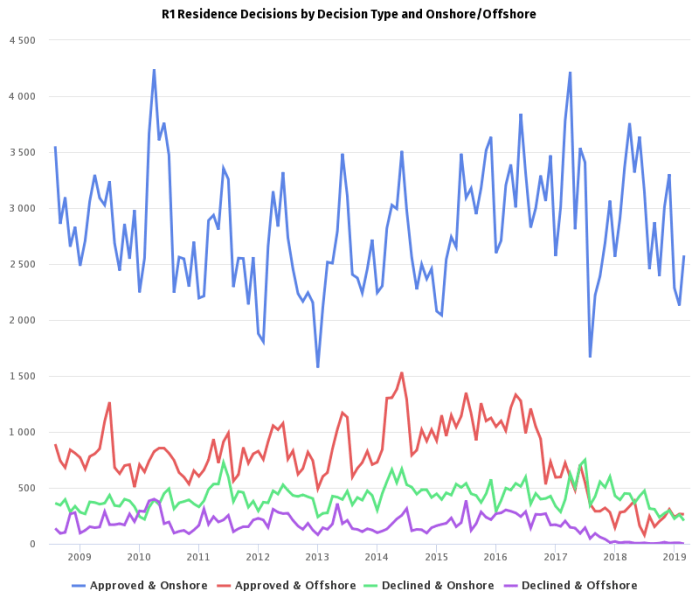

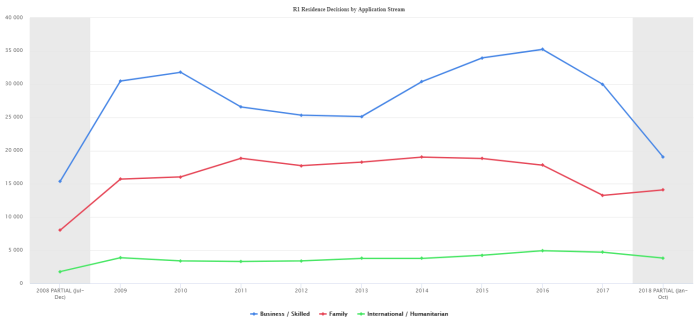

And yet, amid all the breathless gung-ho stuff in the article, there is no mention at all of the substantial decline in the number of residence approvals granted over the last couple of years, no mention of the recent cut in the target rate of residence approvals, and nothing about the plans the government is now working on to managed residence approvals streams differently in future. For anyone interested, I wrote about them here last week.

There are lots of small points I could pick up on. There was the weird statement that “policy plans and population outlooks continue to assume that New Zealand’s net migration will fall back into negative territory”, which simply isn’t true: neither SNZ population projections, nor (say) Reserve Bank or Treasury forecasts assume the net flow turns negative, just that it slows. Or the odd comparison that noted that our peak population growth rate (in 2017) “was more in line with sub-Saharan African countries like Sierra Leone” than with other advanced countries – which might have made for some interesting comparisons (eg around economic performance) but was just left hanging.

But I was more interested in two lines in Friday’s article. First, we had the prominent and doughty academic champion of high rates of immigration, Massey’s Paul Spoonley. who ran this line

More recently we’ve seen issues such as Auckland property prices and the Crafar farms sale. “There are distinct issues that trigger highly negative responses,” says Spoonley.

“What equalises that is the positive economic story and a relatively strong understanding of the role migration plays in that.

“We came through the GFC quite well and have done relatively well since … and what is important in that is the contribution that migration makes.”

I guess if you repeat nonsense often enough some people will believe you. As a reminder:

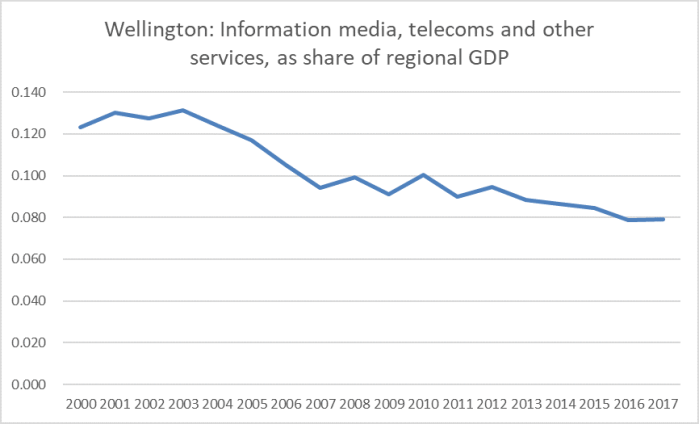

- New Zealand’s economic performance is among the very worst in the OECD, whether one looks back 70 years (about what the post-war immigration surge got going), 50 years, or 30 years,

- There was nothing particularly attractive about New Zealand’s record in the (so-called) GFC, at least if one compares us to other countries with similar sorts of economic management (floating exchange rate, own monetary policy etc),

- And, as even the economists who will champion New Zealand immigration policy will concede, there is no evidence specific to New Zealand that our immigration policy – the most aggressive in the OECD over the last two decades – has contributed to (an imaginery) economic success, or even mitigated our relative failure.

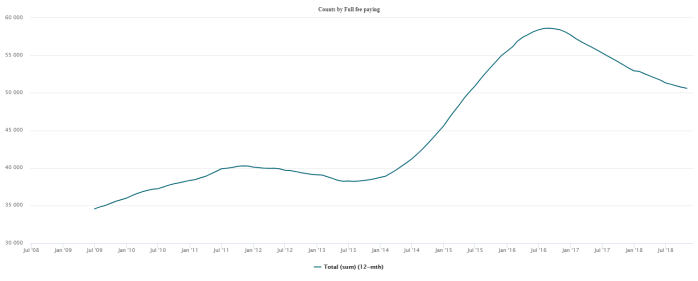

As for the most recent wave of immigration – which Spoonley himself (rather exaggeratedly in my view) describes as unprecedented – here is the chart showing New Zealand labour productivity growth (or near complete lack of it) from Friday’s post.

On matters economic (and he is sociologist not an economist) Spoonley is making stuff up, which Lian Dann happily channels for him.

And then there was the population issue. On Dann’s telling

One thing is for sure: if New Zealand wants to maintain a growing population it needs positive net migration.

and he even gets Statistics New Zealand’s chief demographer in to try to buttress his case

There are other places such as Korea, China and western Europe where the natural rates of fertility are much lower than New Zealand’s.

“In some ways they’re a harbinger of where we’ll be in future decades,” he says.

New Zealand’s total fertility rate has been below replacement for decades now (since about 1980) but with no trend apparent for further drops (the rate is pretty stable at about 1.8 children per woman) – nothing to suggest that our birth rate future is that of Korea or Italy.

But even if our fertility rate were dropping, what of it? Such a drop would presumably be the result of voluntary choices by New Zealand couples. What is it that leads Liam Dann to be so sure that we need, or want, continued population growth? He doesn’t say.

(And doesn’t, for example, mention that – all else equal – more people mean more emissions, not just in New Zealand but (since our emissions per capita are quite high) probably at global level as well.)

And what of Dann’s rather shorter (and thus probably more widely read) column yesterday?

He begins with the tired rhetorical trope

New Zealand has always been a nation of immigrants.The good news is that most of us understand that.

I’m not sure about his background, but I certainly don’t count myself as an immigrant. But even if in some sense his factual statement was true, what of it? It tells us nothing about appropriate immigration policy now (any more than, say, it might have in 1840, had Captain Hobson suggested to the Maori chiefs “you know, this land has always been a nation of immigrants”).

But then he tries to get into substance

However even if numbers ease it seems unlikely that we’ll see a return to the migration outflows we regularly experienced through the past 100 years.

The New Zealand story in the 21st century is very different to the 20th.

For starters our economy is more robust. The peaks and troughs have mellowed.

There are concerns about the fairness of the economic changes made in the 1980s and 1990s but they created a more flexible economy that is less vulnerable to external shocks.

There is so much wrong with this it is hard to know where to start. First, these “significant outflows” were not common at all in our history: net outflows to Australia happened towards the end of the great Australian boom (shortly to be followed by a very nasty bust) in the 1880s, and there were small net outflows in the 1930s (the UK’s experience of the Great Depression was much worse than our own). Significant outflows have only become a feature in New Zealand since our economic performance started lagging so far behind Australia’s. Once we and they had similarly high incomes: these days we are very much the poor relation, and if net outflows to Australia are now not what they once were, it isn’t because those productivity or income gaps have narrowed, but because Australia is much less substantively welcoming to New Zealanders (who can still go any time they like) than they once were. That is probably a wise choice by Australia, but it has further reduced options for New Zealanders.

Second, what about that spin about our economic cycles. Certainly, any boom this last decade has been very (very) subdued – basically not a thing – but perhaps Dann has forgotten that rather severe recession that occurred only 10 years ago. And there is a certain incoherence in the suggestion that the 1980s reforms reduced the likelihood of migration outflows, when many of the large outflows of New Zealanders have occurred in the decades since the reforms.

Ah, but it is not just the economics. We are now such a with-it place that who (decent human beings anyway) wouldn’t want to live in New Zealand.

Then there is New Zealand’s cultural rise on the world stage.

We’re still a minnow but we are visible and our international media stereotype is of a cool, progressive sort of place – rather than a backwater.

The internet and cheap air travel have removed the tyranny of distance. The immigration boom has turned our largest cities into more cosmopolitan places.

New Zealand has become a place that young people are in less of a hurry to leave, a place that those who do leave are more inclined to return to.

It is also a place that potential immigrants are more likely to be aware of.

It is a place those wanting to escape the madness of the wider world aspire to – whether they are Middle Eastern people fleeing war zones, or Brits and Americans seeking more progressive political landscapes.

And yet, as even the Minister of Immigration’s Cabinet paper – discussed last week – noted, we have struggled to attract many really high-quality immigrants. There will always be many poor people happy to move to a relatively prosperous country, if that country will let them in, but not many really able people would have a really remote country, with a poor record on incomes and productivity, as their first choice. Not inconsistent with that, the number of residence approvals has been dropping not rising.

And then Dann returns to the big-New Zealand rhetoric

That’s just as well. New Zealand’s population growth in the 21st century will be tied to immigration.

Our natural birth rate is falling and our population is ageing, following trends in Western Europe and demand.

Without a steady flow of migrants our economy faces stagnation.

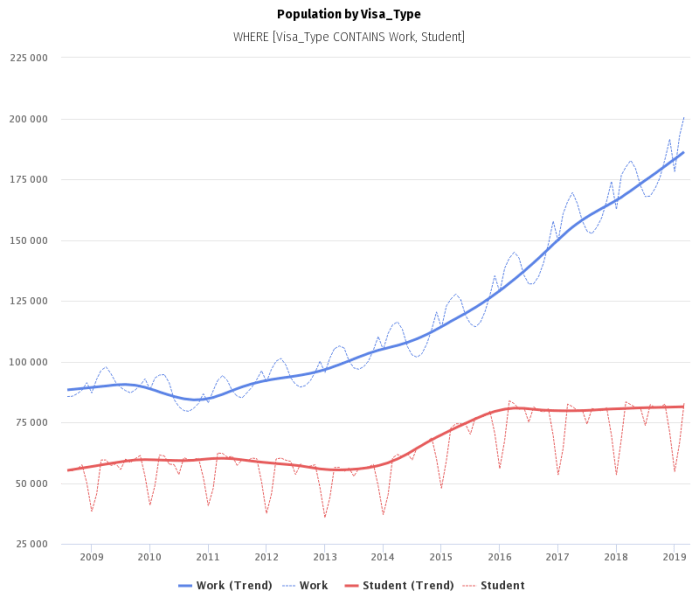

With unemployment at historic lows, an international labour pool prepared to drive trucks, pick fruit and work tough, low-paid shifts in factories, rest homes and hospitals is now crucial to New Zealand’s economic and social wellbeing.

As a factual statement, of course immigration policy will have a huge bearing on New Zealand’s population future. It has almost throughout modern New Zealand history (when immigration was less expansive – between the wars, and from the mid 70s to the late 80s – as well as when the doors are fairly wide open).

But the idea that with a flat, or even modestly falling, population we face economic stagnation, or an inability to manage “economic or social wellbeing”, is – quite simply – unsubstantiated rhetoric that (for example) pays no heed at all to the experience of other advanced countries with fairly flat, or even falling populations. One could add in that unemployment isn’t at historic lows, and that countries with little or no immigration still manage to get the jobs done. It isn’t clear why we should aspire to having more “low-paid shifts in factories” in the first place, but even setting that to one side, economies have ways of adjusting to differing patterns of population growth: some activities just don’t need to be done as much if the population is flat (housebuilding is a good example), and changing relative prices (wages) will draw people into service roles. Unless, of course, immigration policy – as it seems to around, for example, the rest home sector – acts to stymie such adjustment.

I wonder if Liam Dann has any idea how the dozen OECD or EU countries that experienced falling populations in the last decade maanaged?

Central planner to the end, Dann ends his column this way

There’s room for more people in this country. We just need to invest realistically for population growth.

As a matter of geography, there is room for more people. There is physical room in almost country. So perhaps “investment” is the operative word here, and yet we know that rates of business investment in New Zealand (share of GDP) have been towards the bottom of the OECD range for decades even though our population growth rate has been at the upper end of the OECD range. Sure, there are issues about government infrastructure keeping pace with population growth, but the rather bigger issue is that private businesses have not seen the remunerative opportunities to invest here in ways that might have generated the sorts of incomes and material living standards our peers in leading advanced economies – most of them with rather modest rates of population growth – have come to take for granted. That failure – not just this year or last year (although very obviously through this particular immigration surge) – is the market test that the boosters just never grapple with. And before any comes back with a “but housing….New Zealanders invest too much in housing”, recall that (a) conventional wisdom is that there is a shortage, not a surplus, of houses, and (b) that without rapid population growth a much smaller proportion of scarce resources would have to be devoted to building houses.

Recall that the government’s new immigration policy objectives were about improving the wellbeing living standards of New Zealanders. Current immigration policy is failing on that count. In Friday’s article, the Minister of Immigration was running the party line

What we’re interested in is having an immigration system that supports the economic transition to an economy that is more inclusive and more productive.”

Sounds like a worthy goal. Just a shame that productivity growth has been so poor, and exports and imports have been shrinking as share of GDP. Current policy – and whatever tweaks the Minister has in the works – seem unlikely to change that for the better. The policy, in much the current form, has been tried for decades now and has failed.

Big New Zealand – a sentiment championed by too many all the way back to Vogel at least – is a costly delusion. It is past time it was abandoned, and we concentrated on doing much better for the New Zealanders we already have in our remote and unpropitious corner of the world, far from markets, networks, supply chains, and (most)opportunities.