Some months ago, I commented briefly on a speech by the Secretary to the Treasury, Gabs Makhlouf (himself a fairly recent temporary immigrant), in which he had lauded the economic gains to New Zealand from our large-scale non-citizen immigration programme. Makhlouf asserted that:

Migration helps to lift our productive capacity – it enables the economy to grow faster by increasing the size of the workforce, in much the same way that foreign capital allows us to grow faster than domestic savings alone would permit.

Like foreign investment, migrants also bring new skills, new ideas and a diversity of perspectives and experiences that help to make our businesses more innovative and productive.

And perhaps most importantly, migrants often retain strong personal and cultural connections to other parts of the world, which opens up, and helps us to pursue, new business opportunities. We are in a pretty incredible position in this regard, with so many New Zealanders – around 1 million people – living overseas, and so many people who live here having been born in another country.

More recently, I passed on the comment Makhlouf had reportedly made, in an official capacity, that ‘immigration is good, it is as simple as that” (or words to that effect).

Some time ago, I lodged a request with Treasury for copies of any advice they had provided to ministers over the last couple of years on the economic impact of immigration in New Zealand, and on the permanent residence approvals target (currently 45000 to 50000 per annum). I was curious as to see what analysis and argumentation might lie behind their chief executive’s rather gung-ho views, but was really more interested in any economic analysis around the permanent residence approvals target, which I knew had been reviewed last year.

It took quite a while for the papers to be released, but eventually I did get part or all of 21 documents. Treasury suggested that they might put the material on their website, but they do not appear to have done so [UPDATE: a link here], so here is a link to a single pdf which contains all the material they released. Subsequent page references are to this document.

Treasury immigration OIA results

Perhaps what surprised me most – I’m a starry-eyed optimist at heart – is how little substantive material or argumentation there was. I wasn’t expecting a major essay in each paper, but across the 21 papers there just wasn’t much there, even taken together. Having said that, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the advice Treasury staff were providing the Minister seemed rather less glowingly optimistic than the perspectives offered by the Secretary.

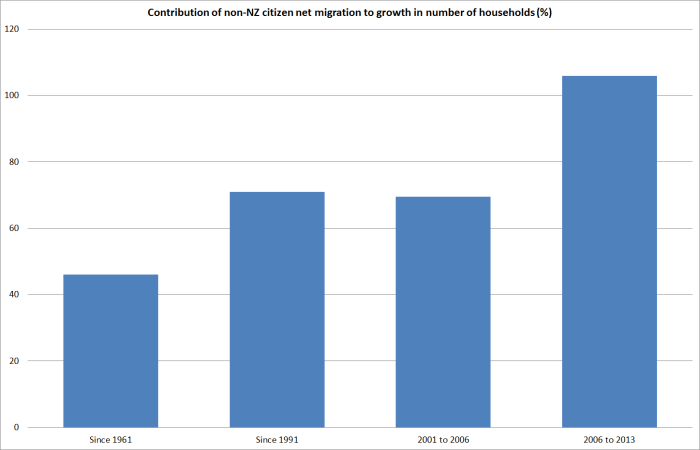

The government sees (and probably previous governments saw) immigration primarily as an economic lever. If so, we do it mostly because we think it benefits us. The non-citizen migration programme is certainly large, and Treasury recognises that New Zealand’s non-citizen immigration programme is one of the largest (as a share of population) of any advanced country. An immigration programme of the size and character of the one New Zealand has run over the last 25 years has changed New Zealand very substantially. Total population continues to increase quite rapidly (not now the case in many other advanced countries), and the ethnic composition of the population has been changing markedly. By sheer scale, it is probably larger than any other aspect of government economic policy in the last 25 years. Statistics record a net 862000 non-citizen permanent and long-term arrivals in the 25 years to March, and the true scale of the inflow is probably larger than that.

But what is there to show for it? The idea is, to quote from two of the Treasury papers:

High-skilled migrant labour increases the average productivity of the labour market, and this is the micro-economic channel through which many of the benefits of immigration accrue (p56)

Granting residence to skilled migrants can increase New Zealand’s human capital by helping meet skill shortages in a growing economy, improving productivity by reducing search costs for employers, and increasing the diversity and innovation of the workforce. These effects can improve labour market productivity over time, which contributes to New Zealand’s overall economic productivity. (page 29)

But there is no evidence of it having happened. We’ve had one of the largest targeted migration programmes anywhere, and there is no sign of any improvement in New Zealand’s productivity performance relative to other advanced economies. In none of these papers is there anything concrete Treasury points to to suggest more favourable outcomes.

An independent economist (and former Treasury staffer) Julie Fry was commissioned by the Treasury’s Macroeconomic Policy team to prepare a paper on links between immigration and New Zealand’s macroeconomic performance. The resulting work last year found its way into a published Treasury Working Paper on the issues. Her abstract read as follows:

New Zealand’s immigration policy settings are based on the assumption that the macroeconomic impacts of immigration may be significantly positive, with at worst small negative effects. However, both large positive and large negative effects are possible. Reviewing the literature, the balance of evidence suggests that while past immigration has, at times, ha significant net benefits, over the past couple of decades the positive effects of immigration on per capita growth, productivity, fiscal balance an mitigating population ageing are likely to have been modest. There is also some evidence that immigration, together with other forms of population growth, has exacerbate pressures on New Zealand’s insufficiently-responsive housing market. Meeting the infrastructure needs of immigrants in an economy with a quite modest rate of national saving may also have diverted resources from productive tradable activities, with negative macroeconomic impacts. Therefore from a macroeconomic perspective, a least regrets approach suggests that immigration policy should be more closely tailored to the economy’s ability to adjust to population increase. At a minimum, this emphasises the importance of improving the economy’s ability to respond to population increase. If this cannot be achieve, there may be merit in considering a reduced immigration target as a tool for easing macroeconomic pressures. More work is require to assess the potential net benefits of an increase in immigration as part of a strategy to pursue scale an agglomeration effects through increase population, or whether a decrease in immigration would facilitate lower interest rates, a lower exchange rate, an more balance growth going forward.

The Fry paper considers a number of my ideas around the potential adverse effects of high rates on inward migration to New Zealand. I don’t entirely agree with her conclusion, which I think is probably too generous to the immigration programme New Zealand has run over the last quarter century, but even her conclusion is modest enough – any gains, from a very large scale programme, are likely to have been “modest”. If so, why bother with the programme?

Just before the Fry paper was released, Treasury wrote an aide-memoire to the Minister of Finance, which they have released in full (from p 18). It is interesting because it is a joint product of the macro policy area of Treasury and more micro-oriented labour market and welfare team. The authors note that “on the whole, The Treasury agrees with the assessment of the evidence in the paper”. They don’t necessarily agree with the policy recommendations, but the government’s principal economic advisory agency apparently sees no reason to be more optimistic about the economic impact of immigration than Fry’s quite downbeat assessment. It is a very different from the tone of Makhlouf’s March 2015 public speech.

As I have noted on various occasions, with a well-functioning market in housing supply and urban land, immigration should have no material or sustained impact on house prices. But if supply is sluggish – as it undoubtedly is in New Zealand, largely for policy-determined reasons – increases in population will put considerable pressure on house and land prices. All New Zealand’s population growth now results from the large non-citizen immigration programme – without it, we would have a flat or slightly falling population. Against this background, it is surprising that the papers Treasury released make very little mention of the implications of the target level of immigration for house prices, in Auckland in particular, and hence for affordability and inequality issues. The young and the poor, the latter disproportionately brown, pay the price of a government commitment to continued high levels of non-citizen immigration. It is not as if other parts of Treasury are oblivious to the problem – this recently released paper on the housing market treats the issue quite well – but it does not seem to have been factored into immigration policy advice.

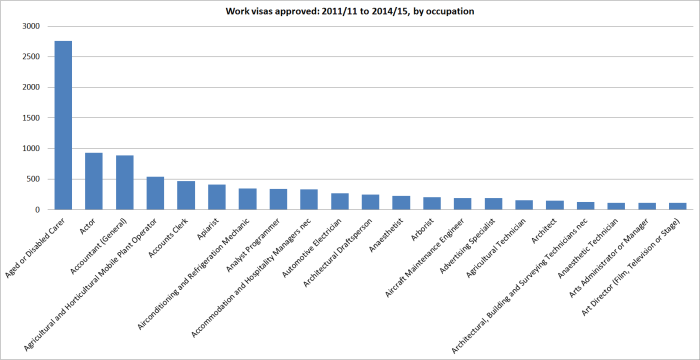

In my macroeconomic arguments about the effects of immigration, I have tended to assume the best about the make-up of the immigration programme itself – that it was bringing in mostly well-qualified people. I was willing to concede that there might be some skills gains, but to argue that these were probably outweighed by the macroeconomic pressures (on real interest and exchange rates). But people keep pointing out that even the skills gains are not as clear one might like to think. Apparently, we’ve given 20000 work visas for chefs in recent years. And Fry points to formal studies showing how disconcertingly long it takes many similarly-qualified immigrants to reach New Zealand native earnings. And, as the Treasury papers show (page 26), over the three years to 2013/14 only around half of permanent residence approvals were to people under the “Skilled/investor” heading (while more than 10 per cent were for the parents of New Zealand citizens or residents).

I had also not paid much attention to the numbers coming under the numerous working holiday schemes that New Zealand is now party to. But Treasury has, and actually recommended to the Minister of Finance last year that a cap should be placed on the numbers coming to New Zealand under the various uncapped working holiday schemes, highlighted a number of risks, including that the substantial growth in the number of working holiday visas might adversely affect employment opportunities for New Zealand young people. This is no small point, since standard analysis (to which I largely subscribe) tends to be very sceptical of the idea that immigration undermines employment prospects, whatever it might do (positively or negatively) to productivity or wages. And it is not just one paper. In another, from December last year, Treasury notes that “immigration policy often involves trading off domestic labour market objectives with other policy objectives” (page 52) – a rather different tone, again, from the Makhlouf speech – and observing that “there is reason to be concerned about the impact some of our current immigration policies may be having on the labour market prospects of low-skill New Zealanders.”

And I’ve already highlighted some of MBIE’s own work suggesting that the investor and entrepreneur immigration categories might struggle to provide much net economic benefit to New Zealanders. There is no sign in these papers that Treasury is any more optimistic.

The other thing I learned from these papers, which I had not previously been aware of, is that when Cabinet reviewed the New Zealand Residence Programme last year, they agreed to set a two-year target rather than a three year one. That was, apparently, partly to shift future decisions, perhaps still triennial, into non-election years. But they also “directed officials to undertake a review of NZRP and report back to Cabinet by November 2015”. Treasury observes (page 53) “MBIE is currently undertaking a strategic review of immigration policy settings. One particular area of interest that has emerged is the extent to which labour market objectives are balanced against goals like foreign policy, tourism and export education”. It all seems a far-cry from a hopeful vision of substantial productivity gains, and beneficial spillovers to long-term New Zealand living standards, from a large scale inward migration programme.

Twenty five years on there is little or no evidence that our very large scale inward migration programme is producing economic benefits for New Zealanders – which should be the principal criterion guiding what is, after all, sold as an “economic lever”. There are some obvious winners – notably those who happened to be property owners in Auckland – but that is purely a redistributional effect, at a serious cost to those who are increasingly squeezed out of being able to afford to buy a house in Auckland. And there are serious reasons to worry that actually the immigration programme has made things worse for New Zealanders, by putting pressure on scarce resources, and driving up real interest and exchange rates, and crowding out much of the sort of business investment we might otherwise have expected after the economy was freed-up in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Secretary to the Treasury is upbeat on the economic benefits to New Zealanders of the immigration programme. But where is his evidence? His staff don’t seem to have been able to find it.

Notwithstanding the prejudices of the elites, there would seem to be a pretty good case now for substantially reducing the non-citizen immigration programme, rather than just pushing on with a failed strategy – a huge intervention in New Zealand’s economy and society for which Treasury can point to no material demonstrable benefits.

Of course, MBIE may yet have the answers. At the same time I lodged the original OIA request with Treasury I lodged a similar one with MBIE, the department with prime responsibility for immigration policy issues. That request is still working its way through the system, more than two months after it was first lodged. I’m beginning to wonder what interesting gems it contains, or (perhaps more saliently) which might yet be deleted and withheld. Two weeks ago I had a friendly email from them telling me I would have the information the following week, and then last week I had another email, from someone further up the hierarchy, telling me that consultation – with the Minister’s office perhaps? – was taking longer than expected, but “we are working to provide a response to you as soon as possible”. It isn’t an overly urgent issue, but it has now been more than two months, and the basic timeframe under the Act is 20 working days.