A week from now Graeme Wheeler will be clearing his desk on his last day as Governor of the Reserve Bank. I’ll have some more to say about his stewardship of the role, either on that last day or perhaps when the Reserve Bank’s Annual Report and the Board’s Annual Report are published – on past practice they should be released any day now, and I suspect Wheeler will want to publish before he leaves office.

But by next Tuesday also, most of the votes in this year’s election will have been counted. Who knows how quickly, or slowly, but we’ll be on course for the formation of a government for the next three years. Either way, change seems likely for the Reserve Bank – and not just the unlawful term of an “acting Governor” , and in time the appointment of a new substantive Governor.

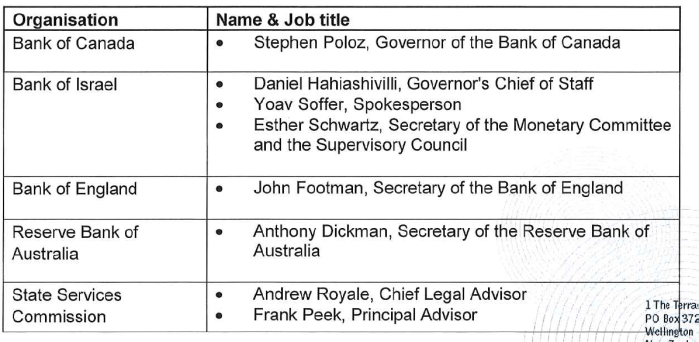

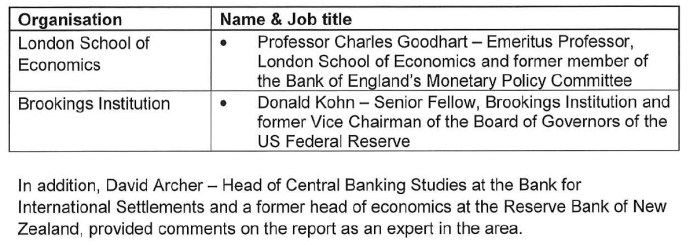

On the National Party side, you’ll recall that the Minister of Finance had Treasury hire former State Services Commissioner (and former Treasury deputy secretary) Iain Rennie to provide some analysis and advice on possible changes to the governance of the Reserve Bank. Having had drafts reviewed by various experts, the report was completed months ago, but hasn’t yet seen the light of day. Treasury has been blocking the release of even drafts of the report, or comments on the draft by reviewers, and nothing is heard from the Minister of Finance. Presumably Rennie didn’t conclude that everything was just fine and no changes were required. Had he done so, there would have been no reason not to publish, and it might even have been a small piece of useful ammunition against the sorts of reforms opposition parties are campaigning on.

The interesting question is (a) how far has Rennie gone in his recommendations, and (b) whether a re-elected National government (perhaps reliant on New Zealand First – long critical of the Reserve Bank) would implement them? I heard the other day a hypothesis that the report isn’t being released because it calls for reform so radical that the Reserve Bank would be split in two (a monetary policy and macro agency, like the Reserve Bank of Australia, and a prudential regulatory agency (like APRA). There are pros and cons to such a structural split, but I haven’t for a long time heard anyone here seriously propose it as an option (and particularly not since the UK government brought all those functions back under one roof). Time will tell, but I would hope Rennie would recommend things like (ideas previously proposed here, and practices in the UK):

- moving (in law) to committee-based decisionmaking,

- having external members appointed directly by the Minister,

- separate committees for monetary policy and the prudential regulatory functions,

- a mandated greater degree of transparency, and

- (something Joyce asked for advice on) making Treasury primarily responsible for the legislation under which the Reserve Bank operates.

As I say, time will tell. But if National is back in office, they will presumably want to move quite quickly on appointing a permanent Governor (the Board, which is driving the process, meets again later this week), and whoever takes the role would presumably want to know what legislative arrangements they would be operating under.

But what if Labour leads the next government? They will have access to the Rennie report, although I had heard that Grant Robertson was quite dismissive when that report was initially commissioned. Perhaps more importantly, they have campaigned on some quite significant changes to the monetary policy side of the Reserve Bank, notably:

- a statutory Monetary Policy Committee, comprising insiders and outsiders, but with all the other members appointed by the Governor himself (and a non-voting Treasury representative),

- adding a goal of full employment to the Bank’s monetary policy objectives, and

- requiring publication of the minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee fairly shortly after any particular interest rate decision.

I’ve written about those proposals on various occasions previously (including here and, more recently, here). In general, I’m sympathetic, but think the governance reforms are excessively timid (and haven’t yet tackled some important issues).

Unsurprisingly, Reserve Bank reform hasn’t a big part of the election campaign. But they were a big part of Alex Tarrant’s interview with Grant Robertson last week. In fact, Robertson’s comments in that interview are by far the fullest I’ve seen since the day the policy was released some months ago. In summary, they only increase my unease and concerns about possible lost opportunities.

Tarrant asked first about the pool of possible people to serve on such a committee

One concern is whether we’d have the depth of talent of candidates for such an outfit not connected to the large banks or businesses.

I’ve never found that a particularly persuasive concern. We manage to run a country with a huge number of public sector board and committees, some on very technical manners and others not. We have a Cabinet after all. And will fill all those posts: the appointees aren’t always exceptional, but then again neither (in this case) are the Governors.

Robertson put his response this way

Robertson reckons we do. “We’ll be looking towards people with monetary policy expertise, in academia. We know that there are people who have served boards before, who have a strength and a knowledge and an understanding of monetary policy,” he says.

“The two ideas we’ve got [for Monetary Policy] are linked, in the sense that we do want to broaden the objectives of the Bank, and so therefore we’ll be looking for people who can bring some knowledge and expertise in the wider macro economy – the way in which employment is going.

Here is, I think, one of the areas in which he is risking making a mistake. Perhaps he could find a decent academic with professional strengths in monetary policy, but there aren’t many of them here, and it isn’t the skill-set that is really most needed. The technical expertise will always reside primarily inside the Bank. What they should be looking for in outsiders to serve on a Monetary Policy Committee is a range of skills, but most of all a cast of mind that will mean those externals don’t just become a front for management. The role needs people who will ask hard questions – some of them technical perhaps, but many no more technical than one would might expect from a good Board director.

Tarrant didn’t raise the issue of who appoints the external members. Robertson’s announced policy had been that the Governor himself would appoint the externals, and control when/if they could speak externally. That would be a serious mistake, and is not a model followed by any of the central banks I’m aware of. Monetary policy is a major aspect of short-term stabilisation policy (ie economic policy), and the decisionmakers should be appointed directly by the Minister of Finance (who is, after all, the only person we voters can hold to account). When I raised this issue with him, he expressed concern that it wouldn’t be a “good look” for him to be grabbing the appointment powers to himself. Frankly, I disagree; it would simply be moving towards standard international practice. As I’ve noted previously, if he wants a Labour precedent, when Tony Blair and Gordon Brown took office in 1997 they reformed the Bank of England, made it operationally independent, established a (statutory) Monetary Policy Committe, and to this day most of the members are appointed directly by the Chancellor of Exchequer. Allowing the Governor to appoint his or her own externals (and a minority of voters at that) is a recipe for maintaining the status quo, not changing it. (After all, the Governor already appoints a couple of external advisers to help him on monetary policy, including (somewhat inappropriately) at present the Prime Minister’s brother.)

Tarrant moves on to the proposed addition of an employment/unemployment objective for monetary policy. We still don’t have many specifics from Labour on how they propose to operationalise this change – a change I generally support. Robertson has talked of getting unemployment down to 4 per cent, but the state of knowledge isn’t such that it would make sense to add a numerical target to a new Policy Targets Agreement. We don’t know what the long-run sustainable rate of unemployment (given eg deographics, labour market institutions, welfare provisions is) but we should want the Reserve Bank to be finding out. By “finding out” I don’t just mean doing a lot of formal research – although that would no doubt be part of the process – but running policy in such a way that reveals, through developments in inflation, when we’ve got unemployment as low as it can sustainably go (ie without other micro reforms).

It looks as though there is quite a bit of work still to do to get this part of the package right. My tuppenceworth is that appointing the right person/people is probably the most important element of the proposed reorientation: you want people making these decisions who realise that the whole point of discretionary monetary policy has always been to get and keep unemployment as low as possible consistent with maintaining price stability. And I’ve previously suggested some specific statutory amendments that would help shift the orientation of the Bank:

- require the Bank to publish updated estimates of the long-run sustainable rate of unemployment (or the NAIRU) at least once a year in the Monetary Policy Statement, and

- require that in each statutorily-required Monetary Policy Statement, the Bank explain the reasons why, in its view, actual unemployment deviates (or is projected to deviate) from the NAIRU, and the steps (if any) the Bank proposes to take to close the gap.

If appointing the right people is critical, what does Robertson have to say about that?

He expresses a modicum of concern that the new [not legally binding] Policy Targets Agreement between the Minister of Finance and Grant Spencer, notionally to come into effect next week, was done without any consultation with him. But his concern comes to not much

Robertson was concerned that he wasn’t consulted when Steven Joyce signed the Policy Targets Agreement with interim governor Grant Spencer for the six-month period following the election. As it happens, he agrees with six months of the status quo. But, “when you’re in that period, immediately before the election, I do believe that it would have been better to have had some input from the Opposition in that.”

And, actually, in normal circumstances under the current law an incoming government would inherit a Policy Targets Agreement (and a Governor) with no automatic right to change that PTA (although new Ministers often ask nicely, and Governors have usually agreed).

Robertson should have been more concerned about the permanent appointments that have been made at the Reserve Bank in recent months, by the outgoing Governor, that risk boxing in a new Governor (and a new government). Robertson’s governance model envisages that the members of the internal Governing Committee would become voting members of the Monetary Policy Committee. But instead of making just an acting appointment to the (Deputy Governor level) role of Head of Financial Stability – to cover the period while the current incumbent serves as “acting Governor – a permanent appointment has already been made. That role was filled by shifting Deputy Governor Geoff Bascand into the role, but then a permanent appointment has also been made – of someone with no obvious value to add to things monetary policy or prudential – as Bascand’s successor as Head of Operations. Surely these permanent appointments should have been left to the new Governor, especially with the prospect of legislative change in the wind whoever leads the next government? Allowing a new CEO to apppoint his own top team, when vacancies exist around the changeover, would seem at very least a common courtesy. And people will exercise the monetary policy votes, not algorithms, so appointing the right people matters.

Strangely, Robertson doesn’t even seem that interested in the appointment of the new Governor, which the (current government appointed) Board has had underway for months. Applications for the job closed weeks before the Labour Party started its dramatic rise in the polls. And yet

So, is he happy with the current set-up where the Finance Minister can veto a board recommendation, but has no other power over the process?

“I’m not proposing any change to that,” he says. “I respect the independence, it’s a very important relationship.” One reason he has been talking about Labour’s designs is to give a heads up to anyone that applies for the job about where he’s coming from.

He keeps going on about “respecting” Reserve Bank independence, but that operational independence – the responsibility to set the OCR independently of direct political involvement – is a totally different matter from appointing the individual who, on current law, will have by far the largest policy influence on the short-term direction of the New Zealand economy. He/she will determine what weight the Bank gives, for example, to the proposed employment objective. And in almost every other advanced economy, the Minister of Finance or head of government has a key role initiating the appointment of the central bank Governor. It is the way normal countries do things (perhaps with some role for non-binding parliamentary confirmation hearings). It is what Philip Hammond or Scott Morrison do. It is what Barack Obama did and (okay…) what Donald Trump shortly will do. Our law should be changed. Perhaps require the Minister to consult the Board – although few if any of them have expertise in public policy or economic management – but put the power, and the responsibility, squarely with the Minister of Finance.

I’m frankly not sure why Labour is so reluctant. They are presented with the ideal opportunity here. When, for example, Gordon Brown reformed the Bank of England he was faced with an experienced incumbent Governor, and a very strong internal deputy – and yet they went ahead with reforms that markedly reduced the power of the Bank, and introduced powerful externals not under the thumb of the Governor. Here, if Labour takes office they will do with a vacancy in the role of Governor. Changing the law regarding the appojntment wouldn’t be a slap in the face to anyone (other than perhaps the Board, who are mostly a pretty faceless and unaccountable lot). I’ve argued that, given the vacancy, one of the first steps of a new government should be a short amending bill to put the appointment power back in the hands of the Minister. At present, he is on track for being presented with a status quo candidate (the Board has pretty consistently defended the status quo) when Labour (and the Greens and New Zealand First) are campaigning on changing the status quo.

What makes me say that? Well, Robertson actually. Because in the interview he says

How about the job description for the next Governor – is he OK with that? “Yes, but, as I say, the reason we gave the speech was to make sure that people were aware that, should we be elected, this is the direction we’re going in. The job description is what it is, as it stands today.”

It is frankly incredible. The job description – which I wrote about here – was decided by the Board, all of whom were appointed by the National government. The members aren’t openly partisan, but they were people National was comfortable with (when Labour was in power, they also had competent people on the Board, but the complexion was a bit different). And the job description is framed under the Act as it stands (and quite rightly so – it is all the Board can do). But Labour is campaigning on material changes to the Reserve Bank Act, to its policy responsibilities, and to the personal powers of the Governor. Surely it would seem likely that a subtly different set of skills would be appropriate under the current Act/PTA, than under whatever Labour and its allies are proposing? Surely, at least to some extent, different sorts of people would be interested in the role (there are, for example, some people who would be resolutely opposed to any suggestion of adding an unemployment target, and might find it very hard to work under such a regime). Even if Labour wasn’t going to adopt my suggestion of amending the Act to take the appointment into the Minister’s hands directly, they should be thinking of sitting down with the Board as soon as they take office, outlining their plans and visions, and inviting the Board to re-open the selection process, now that potential candidates are better placed to know what might be expected of them?

I was also interested in this comment from Robertson

Grant Spencer’s 1-3% target with a 2% mid-point will remain in place over the six months post-election. “We’ve got to take some time to get ourselves in and then have the discussions we want.”

I can understand where he is coming from, but…..parliamentary terms are only three years, and what he is effectively saying here is although he wants the Bank to focus on unemployment as well as inflation he is not going to anything about it until one-sixth of his first term is already over. It wasn’t what Ruth Richardson did in 1990, Winston Peters in 1996, or Michael Cullen in 1999. And even if he can’t amend the Act immediately to establish the employment objective – and getting the details right does matter – it would be quite within his powers to seek an amendment to the Policy Targets Agreement (which, in this case is non-binding anyway) to capture those unemployment concerns straightaway. Given Labour’s clearly stated intention to legislate in this area, it also might not be unreasonable to at least consider use of a section 12 override (although this would probably run head-on into the concerns about the legality of the Spencer term and the supposed PTA).

And, then, finally, there is the large gap in all these reform proposals. Tarrant didn’t ask about it and Robertson has never substantively addressed it. The Reserve Bank has huge discretionary policymaking powers, especially over banks, which are (in law) exercised personally by the Governor, with no adequate accountability framework (nothing like the Policy Targets Agreement for example). Any exercise that opens up the governance of the Reserve Bank – as is likely under any government emerging after the election – has to find a solution to those issues as well. There are questions around which powers should be with the Minister and which with the Bank, and for those exercised by the Bank whether a committee (and if so of what sort) or an individual should (in law) wield them. There are, probably second-order, issues around whether (so-called) macro-prudential analysis and regulation should be governed differently than the day-to-day regulatory regimes applying to banks, insurers, and deposit-takers. I gather Labour recognises that the issues exist, but has as yet not really given any thought to how to resolve the issues. I’m sure Treasury has some advice waiting for whoever does take office.

Robertson has been at pains to stress that the core of the Reserve Bank Act was passed almost 30 years ago (and previous core Reserve Bank Acts didn’t last that long). There are enough issues outstanding – lots not touched on in this post – that doing the reform well really should be quite a major piece of legislation. That will take time, but if he wants to embed change, reorient and lift the overall performance of the institution, he really should be thinking a lot harder (than he appears to be, based on this interview) about ensuring that he acts early to ensure that any government he is a leading figure in can choose as central bank Governor someone they are confident in, both as regards the conduct of policy, and about making effective the sort of structural and cultural changes they talk of.