The government’s Budget Policy Statement and the Treasury’s updated forecasts were released yesterday. I’m not going to comment on the Treasury forecasts in any detail – it doesn’t help that Treasury produces the only PDFs I’ve encountered anywhere that somehow my computer won’t open – although I’d happily bet against their apparent view that the neutral nominal interest rate is still 4.5 per cent and that inflation is going to quickly get back to the middle of the target range.

But two policy initiatives warranted brief comment. First, the resumption of contributions to the New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZSF) is being deferred again. Leveraged speculative investment funds don’t seem a natural activity for governments, and my only disappointment is that the NZSF isn’t being dissolved. As Grant Robertson put it, the further delay will put pressure on future governments to review the age of eligibility for NZS etc. Precisely.

The second initiative was the increase in the capital allowance by $1 billion for the coming financial year. I’m rather sceptical of the quality of much of the government’s capital spending (Transmission Gully, Kiwirail) but this increase shouldn’t be surprising. There are a lot more people in New Zealand than was forecast a few years ago, and people need places to live, schools, road, hospitals, shops, factories etc. A significant chunk of the total capital stock is owned by the government (almost a sixth just by central government) and all else equal, if we have a lot more people more needs to be spent to provide the associated capital stock. That is true in the private sector – houses, shops, factories, offices – and in the public sector. The latest official capital stock data show a net (of depreciation) central government capital stock of around $110 billion. The population shock in the last few years will have been at least 1 per cent, so we shouldn’t be surprised by the need for additional public sector capital spending. It shouldn’t be seen as some sort of discretionary fiscal stimulus or (according to the odd argument Graeme Wheeler ran last week) as a way of easing inflation pressures. It is just something made necessary by the surprisingly strong population. It is a concrete illustration of how demand effects from immigration surprises typically exceed supply effects in the short-run, again contrary to the new Reserve Bank view.

The net capital stock is almost three times annual GDP: each new worker needs the equivalent of three years production in additional capital (whether housing or factories or whatever) New workers add to labour supply, of course but of themselves they don’t directly add to the capital stock. And, as noted, the required addition to the capital stock is large relative to the additional new labour supply in the first year – typically several multiples of it. And we have a new wave of migrants each year, each requiring further additions to the capital stock. Real resources have to be devoted to putting in place that capital stock (we don’t simply import completed houses, roads, schools or office blocks).

None of this should be particularly controversial. If a country’s population is growing faster then, all else equal, the amount (share of GDP) that has to be devoted to investment (capital stock formation) should tend to be larger than otherwise. An acceleration of population growth should be expected to boost investment, and countries with faster population growth rates might be expected to have higher investment/GDP ratios than countries with slower population growth. The differences should be quite stark: a country with 1 per cent per annum population growth might be expected to devote around 3 percentage points of GDP more to investment than the average country with zero population growth. That is just enough more so that the growth in the population would not adversely affect the capital stock per capita. It is never going to be a precise relationship, since there is always a lot else going on. And some countries have patterns of production that are less capital-intensive than others (eg the UK’s financial services industries are probably less capital intensive than Germany’s heavy manufacturing).

But, in fact, the relationship doesn’t look to have been there at all, either historically or more recently.

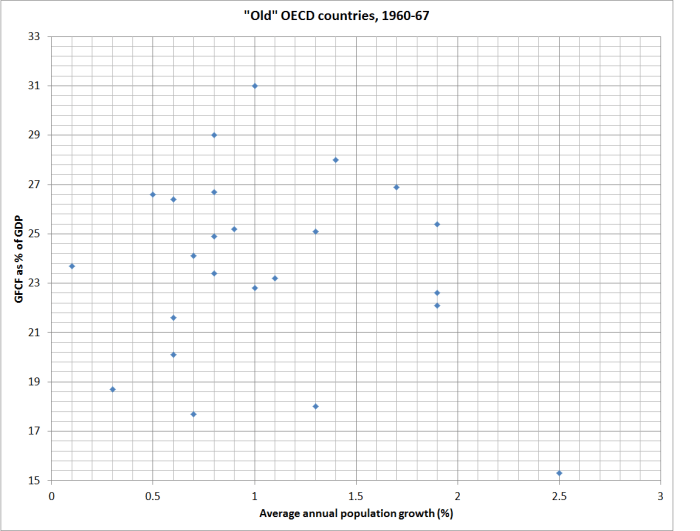

The OECD volume I had down the other day also had data for average annual population growth and gross fixed capital formation for the “old” OECD countries for the 1960 to 1967 period. Here is the scatter plot, with a dot for each country.

There is basically no relationship at all, and certainly nothing as strong as 3 percentage points more of GDP in investment for each 1 percentage point faster annual population growth. It looks as though, across countries,, more rapid population growth tends to crowd out some investment growth. And since everyone needs to live somewhere, and governments have statutory command over resources and fewer market disciplines, the most likely investment to be crowded out is business investment.

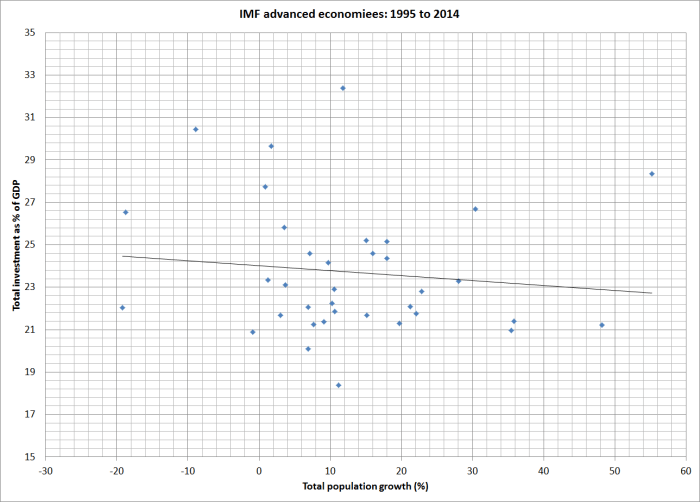

The 1960s is a long time ago. So I also downloaded the same data from the IMF WEO database for each of the advanced countries for the last 20 years (1995 to 2014). Here is the relationship between total population growth and the investment share of GDP. The relationship is basically non-existent, and if anything (not statistically significantly) the relationship is the wrong way round.

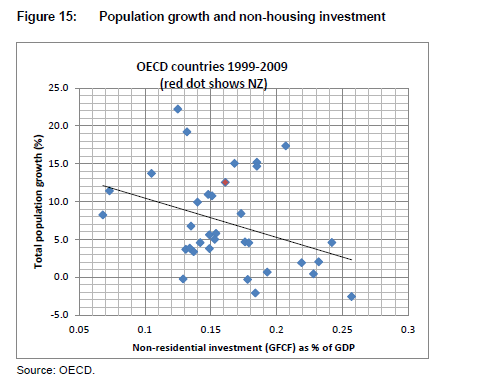

I didn’t have the energy to track down updated non-housing investment data, but I’ve shown previously that there has been a negative relationship between non-housing investment and the rate of population growth across advanced economies.

According to the conventional story, this just should not be happening. After all, our population growth is now largely the result of immigration policy, and high rates of skilled immigration are supposed to spark innovation, skills transfer, and new investment not just to maintain per capita capital stock but to capture the gains to the rest of us from the influx of capable people. In fact, across countries and – as far as we can tell – across time faster population growth tends to squeeze out some business investment in the productive sectors. Why?

There are two ways of articulating the story. Strong demand, reflecting the desire to boost the capital stock to keep pace with the population growth, tends to puts upward pressure on domestic interest rates (relative to those elsewhere). That crowds out some of the desired investment (it just doesn’t happen), especially the return-sensitive business investment. It also tends to raise the exchange rate, providing a double-whammy adverse effect on investment in the tradables sector. Growing per capita exports becomes harder.

The other way of looking at it, is to look at the relative prices of tradables and non-tradables. Tradables prices are determined in world markets, and domestic demand doesn’t really affect them. But non-tradables prices are set in the domestic economy reflecting domestic demand (and underlying productivity growth). High domestic demand associated with rapid population growth tends to raise the prices of non-tradables, and wages, while leaving tradables prices unchanged. That makes it relatively more attractive to produce for the non-tradables sector, all the more so since all tradables production uses (now more expensive) non-tradable inputs. External competitiveness is eroded and investment in non-tradables replaces, to some extent, investment in tradables.

Which brings us back to yesterday’s announcement. The additional government capital expenditure was probably necessary, but at the margin, it will tend to be to squeeze out some other capital investment elsewhere in the economy. The cross-country perspectives suggest that fast population growth will come at the expense of maintaining the per capita capital stock, and make it harder for New Zealanders to keep up, or close the gap on, the incomes of people in other advanced countries.

None of this is new. It was the perspective of able New Zealand economists looking back on the post-war New Zealand experience. Here, for example, is Professor Gary Hawke, writing in the last full economic history of New Zealand in the early 1980s.

the economic consensus is strong one. In essence it simply observes that productivity was highest in agriculture whereas population growth was catered for by the relative expansion of other activities. Population growth thus fostered expansion of relatively low-productivity activities and therefore tended to reduce average per capita income. The key assumption is that sectoral productivities would not have been even more unfavourable in the absence of population growth, and discussion of later chapters shows that assumption to be reasonable….Perhaps if less importance had been attached to full employment, or if a different exchange rate had been implemented, the sectoral productivity trends could have been changed. Perhaps so, but population growth made it more rather than less difficult to effect those changes in policy, even if they had been desired, and, in terms in which it was debated, the economic case against population growth in the post-war economy was always a strong one.

It still is in 21st century New Zealand.