Luci Ellis, head of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s Financial Stability Department,yesterday gave a speech titled “Property Markets and Financial Stability: What do we know so far?, at a real estate symposium at the University of New South Wales.

The Reserve Bank of Australia is a fairly hierarchical organisation, and so although Ellis is a department head, there is an Assistant Governor (several of them) and a Deputy Governor and the Governor above her. It is a reminder of how deep a bench of talented people the RBA has.

I didn’t agree with everything in Ellis’s speech by any means – among other things there is an uncharitable dig at the 1990s RBNZ, and I was surprised to find no references to land use regulation at all – but it is the sort of speech that one comes away from with plenty of food for thought. It is thoughtful and balanced, offering some fresh insights, and reframing other material in an interesting way. It will repay rereading. Taken together with the speech from Wayne Byres, chairman of APRA, that I discussed recently, it is the sort of material that gives one some confidence that the key Australian institutions have thought carefully and deeply about property market issues and risks. And that they have sought to use historical experiences, and those of other countries, for illumination and not just for support. Not everyone in Australia will agree with Luci Ellis’s way of looking at the issues, but it would be foolish not to grapple with the arguments and evidence that people like her advance.

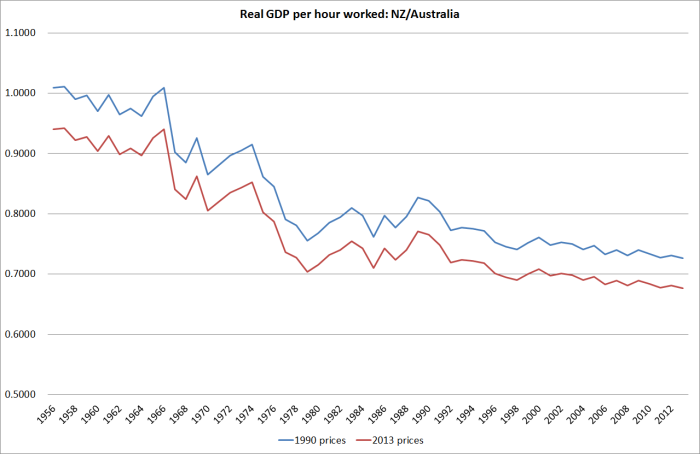

The contrast with our own Reserve Bank is a sorry one. Our central bank does plenty of speeches, but most of them are pretty lightweight affairs. As they will, and must, market commentators scour them for hints about near-term policy direction, but I don’t think any reasonably well-informed observer comes away from a Reserve Bank speech – whether from Wheeler, Spencer, Fiennes, McDermott, or Hodgetts – feeling that they now understand the isssues, or even the nature of the questions, better. Sadly, it isn’t only the Reserve Bank: the quality of the economic analysis from our key economic policy agencies more generally now seems patchy at best. I bang on here about the New Zealand’s slow continued relative economic decline, but when I look at the quality of the policy advice etc (whether it is MBIE or Treasury on (eg) immigration, or the Reserve Bank) I sometimes wonder if we should really be surprised.

I’m not going to try to excerpt Luci Ellis’s speech, simply encourage anyone interested in the substantive issues to read it. Little of it is Australia-specific and many of the insights and questions are relevant to the discussions and debates that should be occurring in New Zealand.

Rather than excerpt the core content of the speech, I want to draw attention to just one section about good public policy processes. Here is what Ellis has to say:

But the policy imperatives inspiring the work make it even more important to be scientific in our approach. By scientific, I mean the idea that the celebrated physicist Richard Feynman talked about in a much-cited university commencement address (Feynman 1974).

“Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can – if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong – to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it.”

It’s an argument for nuance, for being rigorous about your approach and for being prepared to admit you might be wrong. But I don’t want to understate the challenges this poses in a policy institution.

I hadn’t come across Feynman’s speech previously, but it is also worth reading. Here is the fuller version of the bit Luci Ellis quoted from.

It’s a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty–a kind of leaning over backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid–not only what you think is right about it: other causes that could possibly explain your results; and things you thought of that you’ve eliminated by some other experiment, and how they worked–to make sure the other fellow can tell they have been eliminated.

Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can–if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong–to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it. There is also a more subtle problem. When you have put a lot of ideas together to make an elaborate theory, you want to make sure, when explaining what it fits, that those things it fits are not just the things that gave you the idea for the theory; but that the finished theory makes something else come out right, in addition.

In summary, the idea is to give all of the information to help others to judge the value of your contribution; not just the information that leads to judgement in one particular direction or another.

The easiest way to explain this idea is to contrast it, for example, with advertising. Last night I heard that Wesson oil doesn’t soak through food. Well, that’s true. It’s not dishonest; but the thing I’m talking about is not just a matter of not being dishonest; it’s a matter of scientific integrity, which is another level. The fact that should be added to that advertising statement is that no oils soak through food, if operated at a certain temperature. If operated at another temperature, they all will–including Wesson oil. So it’s the implication which has been conveyed, not the fact, which is true, and the difference is what we have to deal with.

And this, I think, is what most seriously troubles me about our own Reserve Bank’s contributions to the discussion of property risks etc. Whether it is speeches from the Deputy Governor, the Governor’s own comments at FEC, consultation documents, and responses to consultation documents, we’ve seen far too little of the sort of scientific integrity that Feynman was talking about. We might not expect much from advertising agencies, or from politicians. But we really should expect it from an independent technocratic agency such as a central bank.

We had some glaring examples of how not to do policy in the Reserve Bank’s processes that led to the decision to treat lending on investment properties as riskier than other housing lending. Ian Harrison documented various examples of selective quotation, dubious use of published studies etc. I gather that the Bank reckons it has found some holes in Ian’s arguments, but it shouldn’t have needed him to be raising the issues at all. We should expect an organisation like the Reserve Bank to go out of its way to make its case, and to make its case more convincing by showing that it was aware of, and had drawn attention to, any potential pitfalls or weaknesses in the arguments, or case, it was making.

My own concern is much more with the new investor finance restrictions. Perhaps they are an appropriate response to the situation, but even if so we will never be able to have a well-founded confidence in such a conclusion because of the poor quality, highly selective, case the Bank has made, the secrecy with which it guards the submissions that were made on its proposals, and the cursory or non-existent responses it has made to concerns and criticisms of its consultative document.

My submission to the Reserve Bank on the proposed restrictions is here. Here is an extract that summarised some of my key concerns

My concerns about the substance of the proposal fall under five headings:

- The failure to demonstrate that the soundness of the financial system is jeopardised (this includes the failure to substantively engage with the results of the Bank’s stress tests).

- The failure of the consultative document to deal remotely adequately, with the Bank’s statutory obligation to use its powers to promote the efficiency of the financial system.

- The failure to demonstrate that the statutory goals the Bank is required to use its power to pursue can only, or are best, pursued with such a direct restriction.

- The lack of any sustained analysis (here or elsewhere in published Bank material) on the similarities and differences between New Zealand’s situation and the situations of those advanced countries that have experienced financial crises primarily related to their domestic housing markets.

- The failure to engage with the uncertainty that the Bank (and all of us) inevitably face in making judgements around the housing market and associated financial risks, and the costs and consequences of being wrong.

The absence of any substantive discussion of the likely distributional consequences of such measures is also disconcerting. Distributional consequences are not something the Reserve Bank has ever been good at analysing. In many respects they were unimportant when the Bank’s prudential powers were being exercised largely through indirect instruments (in particular, capital requirements) but they are much more important when the Bank is considering deploying direct controls. In particular, the combination of tight investor finance restrictions in Auckland and the continuing overall residential mortgage “speed limit” is likely to skew house purchases in Auckland to cashed-up buyers. In effect, to the extent that the restrictions “work” they will provide cheap entry levels. New Zealand first home buyers and prospective small business owners will be disadvantaged, in favour of (for example) non-resident foreign owners. At very least, it should be incumbent on the Bank to spell out the likely nature of these distributional effects.

Conclusion

The restrictions proposed by the Reserve Bank do not pass the test of good policy. The problem definition is inadequate, the supporting analysis is weak, and the alignment between the measures proposed and the statutory provisions that govern the use of the Bank’s regulatory powers is poor..

The Reserve Bank refuses to release the submissions it receives (unlike, say, parliamentary select committees) and instead published what it loosely describes as a “response to submissions”, together with a Regulatory Impact Assessment(RIA). I had intended to comment in detail on these documents, but did not get round to it when they came out a few weeks ago, and won’t bore readers with that now. Instead, lets take a higher level approach.

The RIA is barely five pages long, and two of those pages are largely devoted to three simple charts. There is no attempt at a cost-benefit analysis, or to quantify any of the judgements. There is also little or no engagement with the relevant statutory provisions of the legislation the Reserve Bank operates under.

The response to submissions was 10 pages long, but most of this is devoted to operational details of the proposal, with only three pages given over to the policy issues themselves (is such a restriction an appropriate, and net beneficial, policy response to a real and substantive issue). Although the document is described as a response to submissions, most of the points I included in my summary above are not even mentioned, let alone dealt with or responded to. Since the Bank keeps submissions secret, it is only if submitters themselves choose to publish their own submissions that we can know what points are being made. We should be able to count on a more honest reporting of the issues that have been raised (there were, after all, only 13 submissions).

The Bank may have a strong case for its position, but all it has done – in the consultation document and response – is a piece of advocacy work. It has made no sustained attempt to outline the strengths and the weaknesses of its case. There is, for example, no substantive discussion of the efficiency issues even though financial system efficiency is a key element in the statutory objective and LVR limits cannot but impair the efficiency of the system. And there is no recognition, or consideration of the implications, of the fact that many countries have had rapid credit growth and high house prices, while avoiding a financial crisis. It is simply poor science (in Feynman’s terms) and poor public policy. And the points around the distributional effects of the policy are not even touched on. Such selectivity speaks poorly of the Bank as a public policy agency.

I don’t want to idealise the Australian institutions, which (being comprised of human beings) have made their own misjudgements over the years. But at present the quality of the material the RBA and APRA are putting out shows up the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in a particularly poor light. New Zealanders deserve better from such a powerful institution, and from those who are paid to hold it to account.

Let’s hope they manage a better quality of argument and engagement in the Monetary Policy Statement tomorrow.