A couple of months ago now I wrote a post about the new set of discount rates government agencies are supposed to use in undertaking cost-benefit analysis, whether for new spending projects or for regulatory initiatives. The new, radically altered, framework had come into effect from 1 October last year, but with no publicity (except to the public sector agencies required to use them). The new framework, with much lower discount rates for most core public sector things, wasn’t exactly hidden but it wasn’t advertised either.

My earlier post (probably best read together with this one) was based largely around a public seminar Treasury did finally host in February, the advert for which had belatedly alerted me to this substantial change of policy approach (and sent me off to various background documents on The Treasury website).

As a quick reminder, discount rates matter (typically a lot), as they convert future costs and benefits back into equivalent today’s dollars (present values). The discount rate used makes a big difference: for a benefit in 30 years time discounting at 2 per cent per annum reduces the value by almost half, while converted at 8 per cent the present value of that benefit is reduced by almost 90 per cent.

Until last October, projects and initiatives were to be evaluated at a 5 per cent real discount rate – rather lower than the rates historically used in New Zealand, but not inconsistent with the record low real interest rates experienced around the turn of the decade (recall that the discount rates did not attempt to mimic a bond rate, but took account of the cost of both debt and equity).

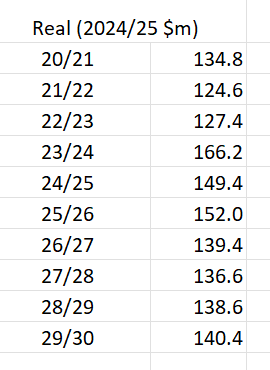

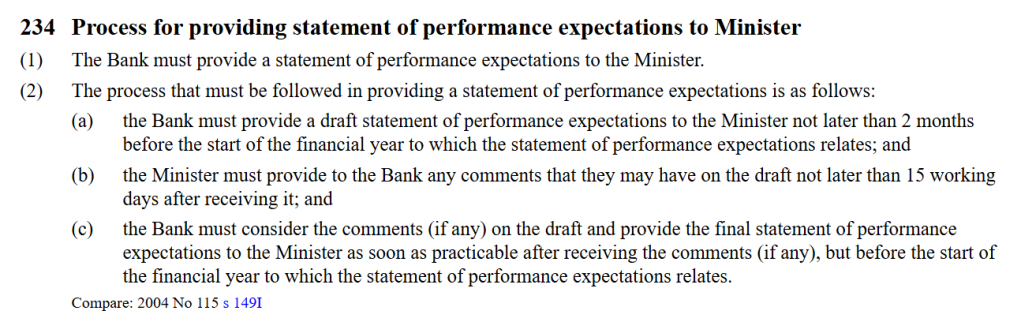

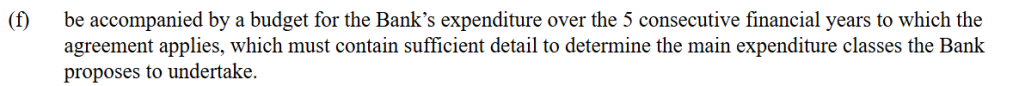

The new framework, summarised in a single table, is

and in case there was any ambiguity about where the focus now lay, not only was the non-commercial proposals line listed first but the circular itself made it clear that the non-commercial rate(s) were likely to be the norm for most public service and Crown entity proposals.

In the earlier post I outlined a bunch of concerns about this new approach, both around the substance and what it might mean for future spending (and, for that matter, regulatory) pressures, and around what appeared to have been quite an extraordinary process, with no public consultation at all. Treasury officials at the seminar had, however, assured me that it had all been approved by the Minister of Finance, which frankly seemed a little odd given the (then) new government’s rhetorical focus on rigorous evaluation of spending proposals etc.

Anyway, I went home and lodged an Official Information Act request with The Treasury. They handled it fairly expeditiously but it took me a while to get round to working my way through the 100+ pages they provided. This was the release they made to me

Treasury OIA re Public Sector Discount Rates March 2025

and this was their advice to the Minister of Finance, already released but buried very deep in a big general release on a range of topics. I’ve saved it here as a separate document.

Treasury Report: Updates to Public Sector Discount Rates 30 July 2024

None of the released material allayed any of my concerns. In fact, those concerns are now amplified, and added to them is a concern about the really poor quality, and loaded nature, of the narrow advice provided to the Minister of Finance on what can be really quite a technical issue but with much wider potential political economy implications. There was an end to be achieved – officials were keen on lower discount rates – and never mind a careful. balanced, and comprehensive perspective. It was perhaps summed up in the comment from one principal adviser who noted “I get a bit lost on the technical back and forth on SOC vs SRTP” but “I support moving to 2%”.

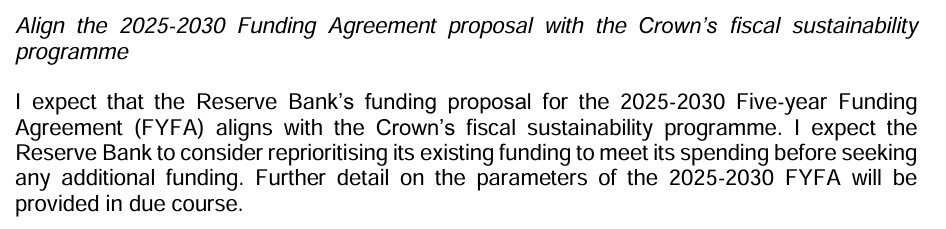

Somewhat amazingly, even though all the documents talk about how a change of this sort really should have ministerial approval – this is even documented in the minutes of The Treasury’s Executive Leadership Team meeting of 12 March 2024 – in the end all they did was ask the Minister to note the change they (officials) were making. All the Minister was asked to agree to was process stuff around the start date and future reviews. I’m surprised that there seems to have been no one in her office – her non-Treasury advisers, who in part are supposed to protect busy and non-technical ministers from officials with an agenda – who appears to have appreciated the significance of what was going on or thus to have triggered a request for more and better analysis/advice. Or even, it appears, to have raised questions about what was behind the comment in the Consultation section of the paper that “To manage risks of raising external expectations and a risk of prolonged debate, we have not consulted publicly”. Were there perhaps alternative perspectives then that the Minister should have been made aware of? (The only people consulted were other public sector chief economists – whose agencies will typically be keen on getting project evaluation thresholds lowered – and a few handpicked consultants.)

What became more apparent in the papers was that this entire project had got going under the previous government (Labour, but with Greens ministers) when the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment had suggested in 2021 that public discount rates should be reviewed with a view to adopting a model that would discount future benefits (relative to upfront costs) less heavily. Treasury had undertaken in 2022 to the (then Labour majority) select committee that they’d do a review. Things seemed to get their own momentum from there, and nothing about either a change in fiscal circumstances – back in 2021/22 even Treasury was keen on spraying public money around – nor a change in government seems to have prompted a pause. Had the new Minister of Finance, or her office, been more alert to the implications, perhaps they’d have called a halt to the work programme (but on this occasion I’m reluctant to put much blame on the Minister, as she appears to have been so badly advised by The Treasury).

The only advice the Minister of Finance appears to have been provided with is the short paper linked to above. It has just over two pages of substance (the rest is process, plus a four page technical appendix – which I’d imagine that, for a noting recommendation only, a busy – and non-technical – minister would not normally read).

It is striking what the Minister is never told:

- there is no mention in the paper that the practical implication of the new approach Treasury was planning to take was that most public sector projects and proposals would be evaluated primary at a 2 per cent real discount rate rather than the (standard) 5 per cent rate previously. They mention that the SOC-based rate is being increased, in line with the increase in bond rates, but never that this discount rate will no longer be used much.

- there is no attempt in the paper to the Minister to explain, or justify, the new approach under which discount rates for years beyond year 30 would be evaluated at even lower discount rates still (there are arguments for and against, but none of it is mentioned and nor are the implications drawn to the Minister’s attention).

- they note the distinction that one rate will be used for commercial projects and one for non-commercial things, but offer no analysis or advice on either why such a distinction should be introduced or how, either conceptually or practically, the two would be distinguished (they promise they would develop future guidance, but this still appears not to have been done).

- they never draw the Minister’s attention to the fact that one can evaluate projects at any rate one chooses but that it does not change the fact that there is a real cost – in debt and equity finance – which isn’t a million miles away from the Social Opportunity Cost (SOC) approach they were planning to move away from. Projects that passed a cost-benefit test at a 2% (or 1%) discount rate but failed to do so using an 8 per cent rate would, if approved, simply be being subsidised by taxpayers.

- they never drew to the Minister’s attention that they were planning to leave the rate of capital charge at 5 per cent, now inconsistent with either approach to discounting and project evaluation

There is also no engagement with some of the conceptual issues raised by what Treasury was planning. This is from my previous post

It is all very well for Treasury to say that every proposal will have to have numbers presented with both a 2% and 8% discount rate, but if they cannot answer simple questions like these (or alert the Minister to them) then all they’ve done is introduced a pro-more-spending muddled model.

Perhaps most breathtaking was the bold claim (offered with no supporting analysis at all) that “The updated discount rates will not change the dollar volume of spending, since individual spending proposals will continue to be prioritised within a budget constraint (fiscal allowances).”

It is the sort of claim that if a first year analyst had made you might take them aside and explain something about incentives, political economy, and what was and wasn’t fixed in the system. This paper was written and signed out by a highly experienced Principal Adviser and a highly experienced Manager, and the policy had been signed off by the entire Executive Leadership group.

Never once it is pointed out to the Minister that budget allowances (whether capital or operating) are hardly immoveable stakes in the ground, enduring come hell or high water from decade to decade. (Why, this very morning, the operating allowance for this year was altered again). Or that the overall effect of what Treasury was planning to do would mean that more projects (spending proposals) and more regulatory initiatives would pass a cost-benefit test and show a positive net present value. And that while, in any particular year, an operating allowance might bind (so that only – at least in principle – the most highly ranked projects (in NPV terms) would get approved, over time if more projects and regulatory proposals showed up with positive NPVs the pressure would be likely to mount – whether from public sector agencies or outside lobby groups – for more spending and more regulation. (In fact, Treasury never even pointed out the operating allowance is a net new initiatives figure and higher taxes can allow higher spending even within that self-imposed temporary constraint.) And that even if a National Party minister might pride herself on her government’s supposed ability to restrain spending, time will pass, governments will change, and future governments that are predisposed to spend more will hold office. Sharply lowering discount rates – to miles below the actual cost of capital – was just an invitation to such governments. It seems like fiscal political economy 101…..and yet not only is this issue not touched on in the advice to the Minister there is no sign of it in any of the other documents Treasury released to me. You wouldn’t get the sense at all either that the fiscal starting point was one in which New Zealand now had one of the largest structural deficits in the advanced world, with even a projected return to surplus years away.

Treasury seems to have just wanted lower discount rates.

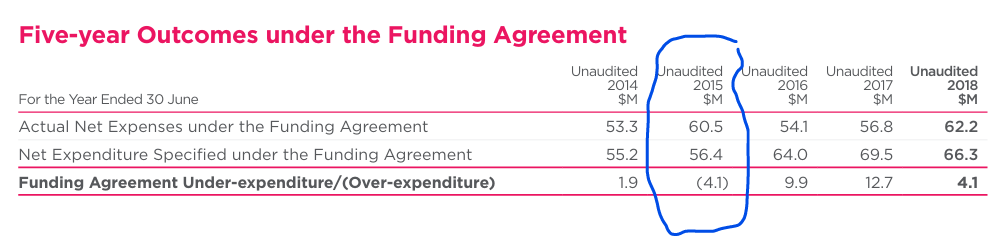

You get this sense in this extract from that short paper to the Minister

Goodness, we wouldn’t want anyone debating the appropriate discount rate would we, so let’s just render it moot by moving to an extremely low rate (in a country with a historically high – by international standards – cost of capital). Or, we don’t anyone fudging their cost-benefit analysis – but isn’t Treasury supposed to be some of gatekeeper and guardian of standards – so we’ll just make it easy and slash the discount rate hugely. And as for that claim that a 5 per cent discount rate – miles below any credible estimate of cost of capital or private sector required hurdle rate of return – incentivises decisionmakers to focus on the short-term, there is no serious (or unserious) analysis presented to the Minister suggesting this was in fact so (that lots of projects with compelling cases were missing out), nor any attempt to suggest that capital is in fact costly, and that when it is costly there should be a high hurdle generally before spending money that has payoffs only far into the future.

There is, you should note, no corresponding paragraph outlining the incentive effects and risks around what Treasury was planning to do.

There was a time when you could count on The Treasury for really good and serious policy advice. If this paper is anything to go by, that day is long past. Changes of this magnitude should have been done only with the Minister’s explicit approval and should probably only have been done after serious and open public consultation. And the Minister was entitled to expect much better, and less loaded, advice than she received on this issue, where what Treasury was planning ran directly counter to the overall direction of the government fiscal policy and spending rhetoric. The Minister herself probably should have had better and more demanding advisers in her office, but really the prime responsibility here for a bad, muddled and ill-justified change of policy rests with The Treasury.

(And in case you think I’m a lone voice in having concerns, here is a column from a former very experienced Treasury official who had considerable experience in these and related issues)

[Further UPDATE 21/5. Consultant and former VUW academic Martin Lally has added his concerns on the substantive issues in two posts here

https://nzae.substack.com/p/social-rate-of-time-preference-lally-one

https://nzae.substack.com/p/social-rate-of-time-preference-lally-two ]