In both monetary policy and policing there is a case for a considerable degree of operational independence from politicians. The case is (by far) strongest in respect of the Police, where it would be just egregiously unacceptable to have a system in which politicians got to decide who was and wasn’t arrested or charged. It isn’t a foolproof system, because Police Commissioners can have their own biases and preferences, and if there are some (eventual) protections against them arresting people for things that aren’t crimes or on allegations that have no real foundations, or against them simply making up evidence, there are no real protections against them just choosing not to enforce the laws Parliament has written. But constabulary independence is better than the alternative.

The case in respect of monetary policy is technocratic, and views have come and gone on the strength of that case. Operational independence has been the fashion of the last few decades, although in many countries (including New Zealand) there has always been scope for political overrides.

But, whatever your views on the case, in a free society operational independence has to be matched by effective accountability. If you wield great power you must be accountable for its use, and “accountability” here cannot just mean something as feeble as having to publish an Annual Report or front up once in a while at a select committee. The standard form of accountability – really in any job, but certainly in public life – is the threat of losing your job. That is, after all, what happens to politicians: when enough of us disapprove enough of their performance they lose the election, and office.

Both the Police Commissioner and the Reserve Bank Governor can be dismissed, but it is interesting to compare and contrast the statutory provisions.

First, from the Policing Act 2008

I hadn’t known until yesterday (when stories were around as to whether the new Minister of Police would or would not express confidence in the current Commissioner) that the Police Commissioner could be dismissed at will. It isn’t old legislation, and there don’t seem to be any process etc requirements in the Act around potential dismissal. All it seems to take is the signature of the Governor-General acting on advice.

My family used to be keen watchers of the New York police show Blue Bloods and I was always struck then by the fact that the mayor could dismiss the police commissioner at will, a point both (fictional) parties noted fairly often. It had the feel then of something open to abuse (and like all these things, in practice conventions and ex post scrutiny act as restraints) but I guess it recognises that ultimately the law and the enforcement of the law – the coercive powers of the state – are political matters.

To be honest, dismissal at will (with no compensation) seems a rather dangerous provision when it comes to the Commissioner of Police. It might be quite reasonable for a new government to want a different style of policing, and thus a different sort of person to run the Police, but if so they should be prepared to (and required to) state their reasons, and offer some compensation for loss of office. But what we shouldn’t want is a Commissioner of Police pandering to the minister behind the scenes to save his or her job, whether the pander involved things nearer to policy or things nearer to protection for some mate of a government (the latter might seem low risk, but we build institutions against tough times and risks of attempts to pervert the system).

I’m not overly interested in Police or the current Commissioner, and don’t have any strong views on his fate (although it probably isn’t irrelevant that his term only has 16 months to run) but I am interested in the Reserve Bank, and particularly the contrast between the dismissal provisions for the Police Commissioner and those who exercise official power at the Bank, notably the Governor. The statutory provisions in the Reserve Bank legislation are a little more complex.

Take the Governor first

The Governor can be dismissed at any time, but only “for just cause”. That immediately makes it much harder to dismiss a Governor, because it injects the potential for the courts to become involved in reviewing whether any cause cited by a Minister of Finance in dismissing the Governor was a just one. That makes dismissal almost inconceivable as a practical option, except perhaps in a truly egregious case of public disgrace (eg Governor charged with a serious criminal offence), or physical or mental incapability, because with so much power resting in the Bank we could not reasonably have months of market uncertainty while a court process, and appeals, were worked through.

What might constitute a just cause? You’ll notice in section 90(2) there are two sub-clauses. The first (2a) allows the Minister to seek to dismiss the Governor if (and only if) the Bank’s Board has made a recommendation to dismiss (for the current situation, remember that the entire Board was appointed in one go by the previous Labour government, and signed off on the Governor’s reappointment only last year). That particular provision is narrow – relating specifically to relations between the Governor and the Board.

The more general case is 2b, where the Minister can seek to dismiss whether or not the Board agrees. And what does the Act say counts as “just cause”?

It needs to be read together with this, which applies also to other MPC members

It is a long list, but it is really quite restrictive. Against the backdrop of Adrian Orr’s performance, probably only 92(1a) and 25(1a) are likely to be relevant. And, although the lawyers may have a different view, I’ve take these provisions as applying only to things done (or at least apparent) in the Governor’s current term of office. It isn’t obvious that he could be dismissed for the failures (of which there were many) in his first term, which expired in March this year, even if those failures were captured by these specific grounds for dismissal.

What of 92(1a)? I doubt anyone could mount a seriously credible argument that Orr was unable to perform the duties of his office or that he had neglected his duties (his focus on many other things not his responsibility notwithstanding). What of “misconduct”? I reckon actively misleading (or worse) the Finance and Expenditure Committee this year should count – it is a clear breach of Parliament’s own rules – but…..it is probably a stretch against the wording of this particular piece of legislation.

And so that brings us to section 25 in the schedule covering MPC members, including the Governor. On paper, 25(1)(a) sounds most promising. But what are the ‘collective duties’ of the MPC?

The MPC, under the lead of the dominant Governor, may have burned through $12 billion of taxpayers’ money, delivered inflation well above target for three years in a row, failed to deliver much in the way of speeches or serious supporting analysis……..all things that seem like clear marks of failure in the job, but it is simply impossible to envisage a court accepting that policy was not formulated (at the time) in a manner consistent with the Remit. It clearly was. It was just done very very badly, with not a sign of any contrition since from any of them. The sort of thing that should mean you could lose your job. But not, it appears, when you are the Governor or MPC member. Could continuing to run a big open punt on the bond market now (years on from Covid) count? I doubt it, as I doubt it would be considered now as “formulating monetary policy”, and it clearly had the support of the Board and the previous Minister of Finance.

The final possibility might be

I don’t think actively attempting to mislead FEC, in his role as Governor and MPC member, is acting “with honesty and integrity”…..but it seems a stretch.

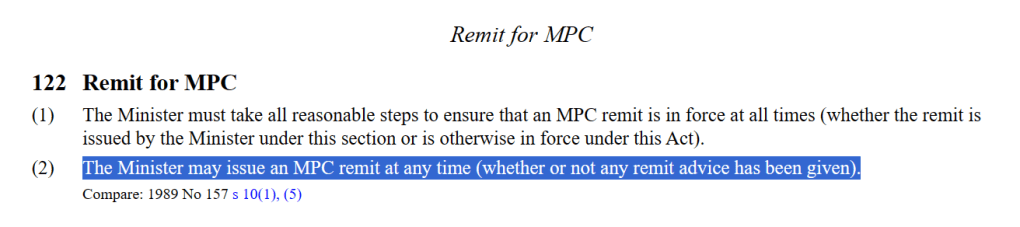

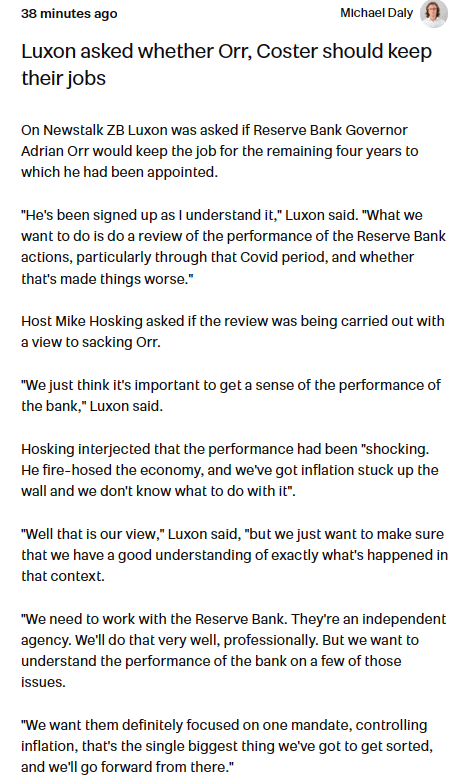

Were Orr operating under Police Commissioner rules (law) he – and his fellow MPC members (especially the externals) – could be dismissed at will. It is not a choice that should ever be made lightly (and the terms of two externals in any case expire shortly), but when you (individually and collectively) have done as badly as Orr and his colleagues have in recent years it should be an option open to an incoming Minister. After all, the new government can impose a new Remit – against which the MPC has to operate – pretty much at will (doesn’t require legislation, at least within quite wide bounds) so why shouldn’t it be able to dismiss the key individuals and ensure that those holding these powerful offices genuinely enjoy the confidence of ministers?

If I could wave a wand I’d make it easier to dismiss Governors and MPC members and a bit harder to dismiss the Police Commissioner. As it is, it reminds me of an article I wrote perhaps 15 years ago – which the the Bank’s Board weren’t too comfortable with and insisted on changes – suggesting that in practice accountability for the Governor mostly existed at the point of reappointment. And since then governments have amended the legislation to make it a bit harder to dismiss the Governor, while limiting to two the number of terms any Governor can serve. Over the objection of the Opposition parties, Robertson chose to reappoint Orr last year, and since he is now on his second term (as are all the external MPC members) and can’t be reappointed again we are in this unacceptable position of someone exercising enormous power (doing it poorly, and having done a particularly poor job in recent years) and facing no effective accountability at all.

Of course, there are always options of seeking to buy out the Governor – whether directly or through the offer of another public role – but that would be to reward failure and poor performance, not punish it.

Were the Governor an honourable man he would already have resigned. But were he an honourable man he would at some point have expressed some serious contrition in recent years. Instead, he wields the power and we – and the incoming government – are left with massive financial losses, a huge inflation shock, and a poorly performing institution.