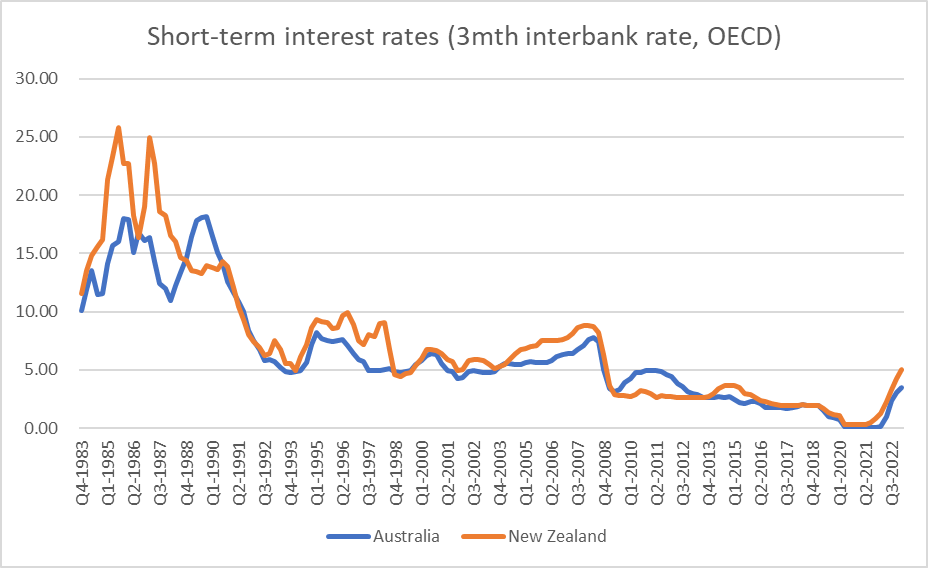

The Reserve Bank of Australia yesterday left its policy rate unchanged at 3.6 per cent. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s MPC is generally expected to today raise its OCR by another 25 basis points to 5 per cent.

In the broad sweep of decades it isn’t an unusually large gap. Most of the time, New Zealand short-term nominal interest rates are at least a bit higher than those in Australia (Australia’s inflation target is a little lower than New Zealand so the real interest differential tends to be a bit larger).

Sometimes economic circumstances in the two countries are very different. Thus, that period a decade or so ago when the RBA cash rate was higher than the RBNZ OCR coincided with the later stages of the Australian mining investment boom, for which there was nothing comparable in New Zealand.

But over the last two or three years, the similarities have seemed more evident. Both countries of course went through Covid, with overall quite similar virus/restrictions experiences. Prolonged closed borders affected both countries, notably the important tourism and export education sectors. Both had very expansionary macro policies. In the scheme of thing, both opened up at about the same time. Both have been characterised by labour shortages and very low rates of unemployment. And both have seen inflation sky-rocket, whether on headline or core measures.

There are differences of course. Take commodity prices as an example. If world prices have recently been falling for both countries, relative to levels just a couple of years back Australian incomes are still being supported much more by the high level of commodity prices.

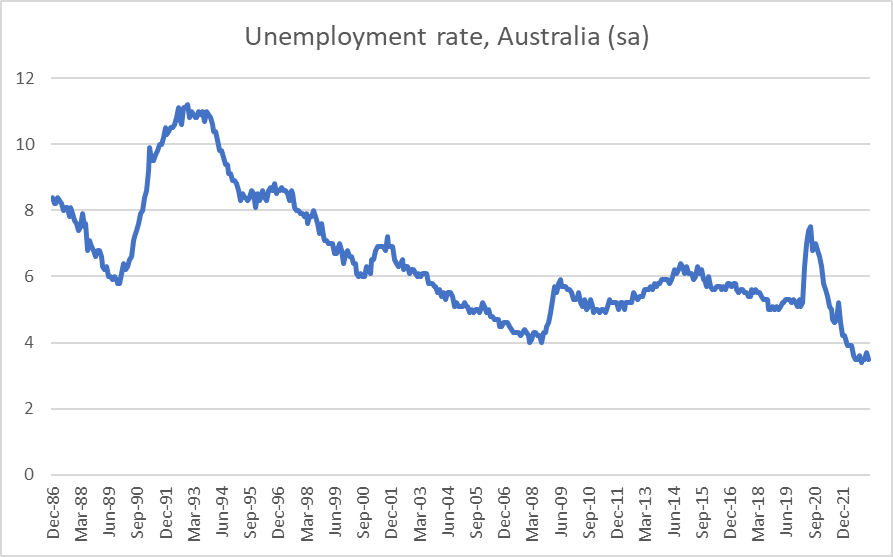

What of the respective unemployment rates? Both are very low, but if anything Australia’s seems lower relative to (a) history and (b) likely NAIRU. Australia’s current unemployment rate is a half percentage point lower than the previous cyclical low, and has not yet shown any sign of lifting.

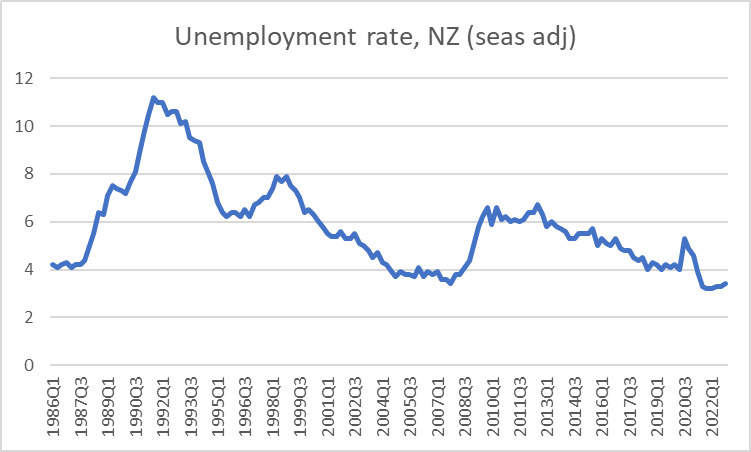

New Zealand’s unemployment rate (quarterly only) seems already to be off its trough and is now about the same as the unsustainably low level reached late in the 00s boom.

One can’t make much of that difference – and the unemployment rate isn’t the only relevant labour market indicator – but the comparison doesn’t obviously point to the RBA needing to do less than the RBNZ. As far as I can see, business survey measures suggest that difficulty of finding labour may have been easing a bit more in New Zealand than is yet apparent in Australia.

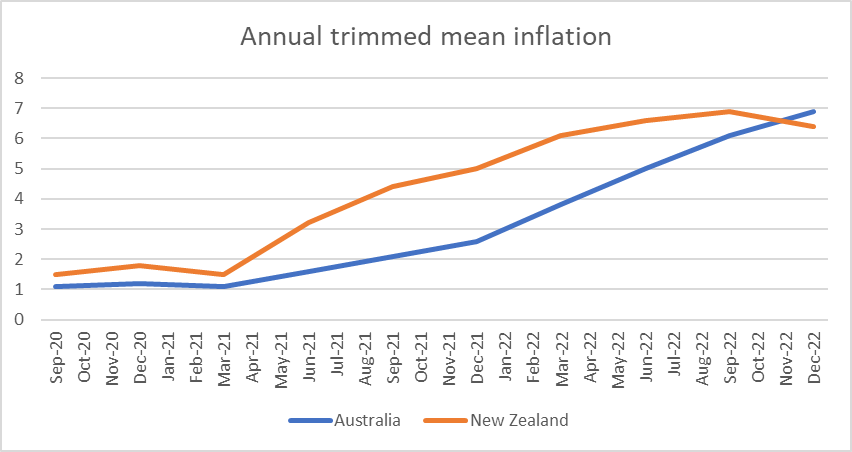

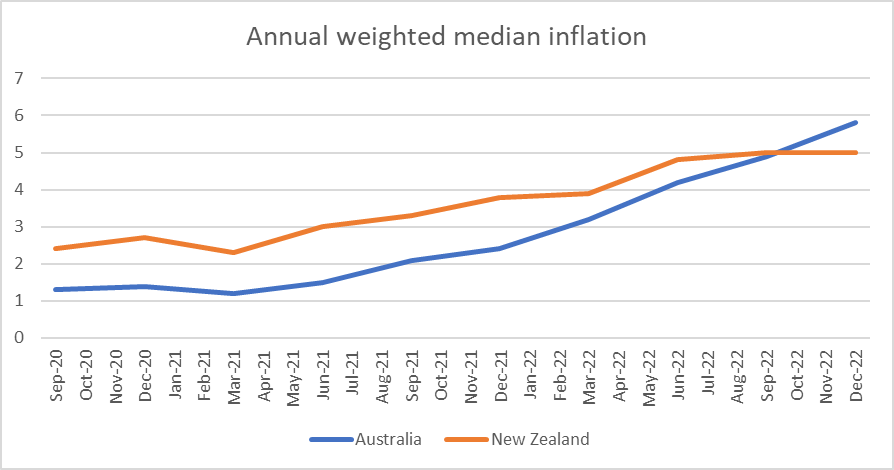

What about (core) inflation measures themselves? Bear in mind that the Australian inflation target is centred on 2.5 per cent and the New Zealand one is centred on 2 per cent.

Here is the annual trimmed mean measure of core CPI inflation for the two countries

And here are the annual weighted median measures

Core inflation started higher in New Zealand than in Australia (the RBA had been badly undershooting the target in the late 10s) but on both annual measures (a) New Zealand annual core inflation appears to have levelled out and (b) Australian core CPI annual inflation now appears to be higher than that in New Zealand. The differences between the two countries core inflation rates in the most recent quarter are more or less in line with the differences in the respective inflation target.

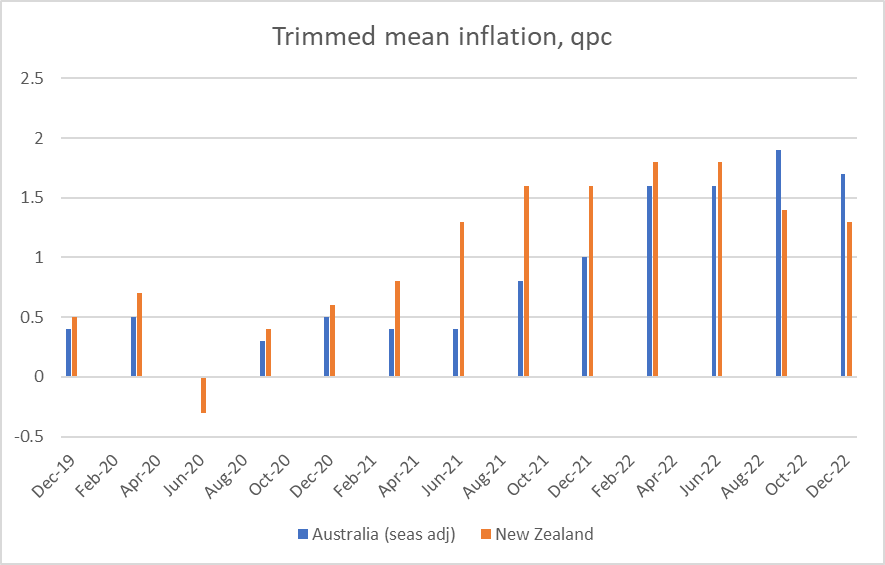

What about the quarterly measures? Here there is some difficulty because the ABS produces seasonally adjusted measures and SNZ does not. Eyeballing the New Zealand series there appears to be some seasonality, although not terribly strong.

Here are the quarterly trimmed mean inflation rates

and here are the weighted medians

The latest observations for the two series for Australia are quite similar (1.6 and 1.7) but there is quite a divergence in the two NZ series (0.9 and 1.3). But in both series there are signs the NZ peak has passed (if you worry about seasonality, even the latest quarterly observations are lower than those a year earlier), while there is no such sign in the Australian quarterly data. And while one can’t meaningfully annualise these data, the differences in the quarterly inflation rates look like more than is really consistent with the differences in the respective inflation data.

I’m not here running a strong view on whether one of these two central banks is right and the other wrong. But it remains a challenge to see how both can be right at present. The two central banks tend to articulate somewhat different models (I’m always surprised at the weight the RBA appears to continue to place on wage inflation, in rhetoric that sometimes seems misplaced from the 1980s), central banks are shaped by their past (the RBA was badly undershooting the inflation target pre-Covid), the political climates are now different (the RBA Governor’s term expires shortly, and governance reforms are in the wind) and there are other material differences in the demand pressures in the two economies that I’ve not touched on here (eg New Zealand has had a bigger housebuilding boom and may be exposed to a deeper bust).

Neither central bank has handled the last three years particularly well – or we wouldn’t have that unacceptably high core inflation – and I am far from being the RBNZ’s biggest fan, but for now my sense is that they are probably closer to right than the RBA is. That may, of course, mean that the near-inevitable recession is nearer at hand here than in Australia.

It might be prudent if the RBNZ holds off raising rates further for now too?

LikeLike

I’m on the fence as to whether a OCR increase today makes sense, and would expect (data dependent of course) no further ones are. They do need to be fairly sure they have done enough to get inflation back down fairly fast and their forecasting models haven’t been working that well in recent years, so hard to be sure .

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

Did the RB make the correct decision?

Certainly, it seems that our economy leapt off the cliff last December. I have never seen the New Zealand economy facing poorer prospects, or being so unbalanced, in my lifetime. Our economic prospects now seem to me to be worse than during the early 1990s or 2008.

The size of government has grown exponentially over the past five years. At the same time, the private sector has been wilfully vandalised by the government. The government response to Covid amounted to economic sabotage. This is shown in our current account deficit, which is the worst in the OECD, and in our history, at 8.9% of GDP. I expect this current account deficit to blow out, to over 10% of GDP.

The problem is, there are two distinct possibilities for our likely economic recession. There could eventually be deflation (similar to the Great Depression), or there could be stagflation (like the 1970s and 1980s).

There are many factors making stagflation likely:

1. The New Zealand exchange rate appears 10 – 20% overvalued to me, given the aforementioned current account balance. A currency crash could cause stagflation, by pushing up the price of energy.

2. Kommissar Robbo has another budget to deliver, during election year. He is addicted to public spending. Who would bet against him gorging on poorly targeted spending once again? This wild public spending could also fuel stagflation.

3. Kommissar Wood has implemented centralised wage fixing. During election year, he will likely splash the cash giving huge wage hikes, thereby fuelling a wage-price spiral.

4. The rebuild from the floods is transitory, but will also be inflationary.

Personally, if I was Governor of the RB, I would be issuing warnings to Kommissar’s Hipkins, Robbo and Wood, saying that they need show fiscal restraint and competence, or the RB will need to offset their stupidity with further rate hikes.

I’m not sure that a 50 bps hike was the correct move. Nonetheless, I have some sympathy for the RB. We have the worst government in our history. Mortgage holders are being made to pay for Kommissar Robbo’s lack of discipline.

All in all, the economy is a train wreck. Who would have thought far left economic policies don’t work?

LikeLike

Hi Michael. and the gap just got bigger, with NZ OCR now 5.25% versus RBA cash 3.6%. One way i can reconcile the difference (not necessarily justify it) is they have different strategies/tactics to bring inflation lower – rather than any differences in their analysis of the current situation or the outlook. My sense is the RBA is hoping to get bailed out by the global tightening in policy – which if its severe enough on global growth, will allow lower inflation to be imported to Australia to some degree. After all, Australia’s (and NZ’s) currently high inflation rate owes as much to global factors as anything domestic. RBNZ is taking more concerted steps to squash inflation by its own actions. Their Feb forecasts seem to make this clear. Both NZ and Aus have roughly 3.5% unemployment rates. the RBA forecasts 4-4.5% in years ahead and the RBNZ 5.6/5.7% – and a recession. the RBA could look like chumps or champs in a few years time.

LikeLike

Thanks Peter. I guess the RBA got (very) lucky in 2008. Not sure that punting on a v nasty global outcome – or all other central banks doing the work – esp when the AUD will tend to fall in a global recession is first-best central banking!

But, as you say, they could get lucky. Still not sure quite what I make of the RBNZ today – the scale of their move, and deliberate choice to surprise, doesn’t seem overly well justified in the statement.

LikeLike