A standard proposition in the literature on delegating public powers to unelected (agents or) agencies in a free and democratic society is that such agencies should operate in a way that leaves no basis for any reasonable person to suspect that those running the agencies are using their platform, and the associated public resources and powers, for any purpose other than the very specific ones Parliament has provided those powers/resources for. Abuses and departures from this norm need not – and fortunately in New Zealand rarely do – involve officeholders seeking to personally enrich themselves or their families. Here it is more likely to take the form of using the platform/powers provided for specific narrow purposes to advance the personal ideological and policy preferences of top managers/Board in quite unrelated areas.

The fact that those individuals, in abusing their powers, do so believing – probably quite sincerely – that they are doing so in some conception of the “public interest” is wholly beside the point. We have elections, and a wider of contest of ideas in the public square, to advance causes. The fact that those individuals might be advancing the views of the government of the day is not just beside the point, but getting towards the heart of it. The whole case – the only real case – for delegating substantive policymaking powers (as distinct from narrow implementation/operations) rests with the notions that (a) the policy in question is separable from the rest of policy, and (b) those charged with it won’t be pursuing partisan or ideological agendas. If not, we might as well have elected ministers make decisions (we can kick them out) and keep the agencies quietly in the backroom as advisers and implementers.

Central banks – or rather central bankers – have long been at risk of falling into this trap, particularly as more of them were granted operational autonomy around monetary policy. Rightly or wrongly, people tend to pay quite a bit of attention to central banks (probably rightly given how much difference their monetary policy actions can make to economic outcomes over, say, a 1 to 3 year horizon). When they speak, the idea has been their words on monetary policy should influence expectations and behaviour – on the presumption that the speaker has no agenda other than the narrow one s/he is charged with. Central banks are also often supposed to be a repository of expertise and wisdom. Sadly, even in the narrow specialist areas central banks have formal responsibility for that, too often neither has really been true (that isn’t just a comment about New Zealand). But central banks do tend to have lots of resources, and provide cheap copy for media (literally, presumably, in the case of op-eds like the Governor’s one that I wrote about earlier this week).

But if your central bankers are using their position to advance personal ideological or partisan agendas – or are perceived to be doing so, even if that is not their conscious intent – the legitimacy and authority of the institution itself will be damaged. And if you believe that gubernatorial words can usefully shape expectations, it is likely that the effectiveness of the institution will be eroded as well. A Labour voter will be less inclined to give serious heed to a Governor suspected of serving National interests or ideological preferences than if they think that person is only interested in doing his/her specific job. And vice versa if the roles are reversed. And if a Governor is perceived to be advancing partisan interests, the effectiveness of that Governor when operating under a government of a different political stripe is also likely to be impeded.

Wise people who have been “inside the temple” recognise the issue and risks. Academic and former Bank of England MPC member Willem Buiter has written about it, as has former Fed vice-chair Alan Blinder. More recently, former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker devoted an entire book to the issues around Unelected Power. It has also been a theme of mine.

Don Brash was Governor of the Reserve Bank for a long time. Before coming to the Bank he’d been an unsuccessful National Party candidate. After he left the Bank he went straight into Parliament as a National Party MP and later was briefly the ACT leader. His interests always seemed more in ideas/policies than in specific parties, but there wasn’t much doubt about where on the spectrum of policy preferences he stood. In some quarters, even if he never said anything much on topics outside his remit, that left a residue of mistrust. I doubt Jim Anderton, or perhaps even Winston Peters, even really saw him as a neutral technocratic figure. But probably where Don really stepped over the mark was quite late in his time at the Reserve Bank, with his speech to the 2001 Knowledge Wave conference. (I wrote about it here.) The details don’t matter now, but it saw the unelected Governor use his position to champion policies that bore no relation to matters he was responsible for. As it happens, in many/most cases they were quite at odds with the views of the government of the day, but it should have been just as unacceptable had he been championing preferences of that particular government. Senior staff, including me, advised him against it – and the version delivered was materially less out of line than the draft – in many cases, including mine, even if we happened to personally agree with the substance of what the Governor was saying. Fortunately Don welcomed challenge/dissent/debate.

One can debate the strengths and weaknesses and records of the two subsequent Governors. I imagine that both were fairly sympathetic to the governments of the day when they were first appointed, but there was never much ground to suppose that either was using his office to openly advance his personal ideological or political agendas.

With the current Governor, now almost halfway through his five year term, almost from the first he has consistently used his office to openly champion causes for which he has no responsibility, even as his actual conduct in the things he is responsible for leaves a great deal to be desired. If the Governor presided over consistently excellent, ahead of the game, monetary policy, if his radical policy initiatives around banking regulation had been well-grounded and authoritative, perhaps the wider abuse of office would be a little less worrying – a worrying foible perhaps, but arguably incidental to the success of the stewardship of the things he was responsible for. It would still be worrying – as it would if, for example, the Chief Justice or the Police Commissioner were openly using their offices to advance their personal political agendas – but underlying excellence tends to buy some grudging respect.

Sadly, that isn’t the Orr Reserve Bank. It is as if the Governor really isn’t very interested in his core functions or even in building strong core capability beneath him. Transparency and accountability around core responsibilities also seem to be alien concepts. Openness to debate and challenge – whether inside or outside the Bank – on core responsibilities also seem alien to him. And, on the other hand, is very interested in using his powerful position to champion all sorts of issues dear to his own heart, and that of his ideological allies. I don’t suppose the Governor necessarily sees himself as championing Labour’s interests or that of the Green Party (the two he would seem to have most in common with) but that is the effect when he weighs in on one topic after another, never in much depth, but consistently advancing those personal agendas in a quite undisciplined way.

There has been example after example of this sort of thing going back to when he first took office in 2018, whether it was views on agriculture, on infrastructure, on climate change, on fiscal policy, on Maori economic development, alleged short-termism or whatever. It remains notable just how few, and unserious, have been the Governor’s speeches on core responsibilities, and how many his speeches and commentaries on these other issues. It flows down the organisation. We had another example yesterday.

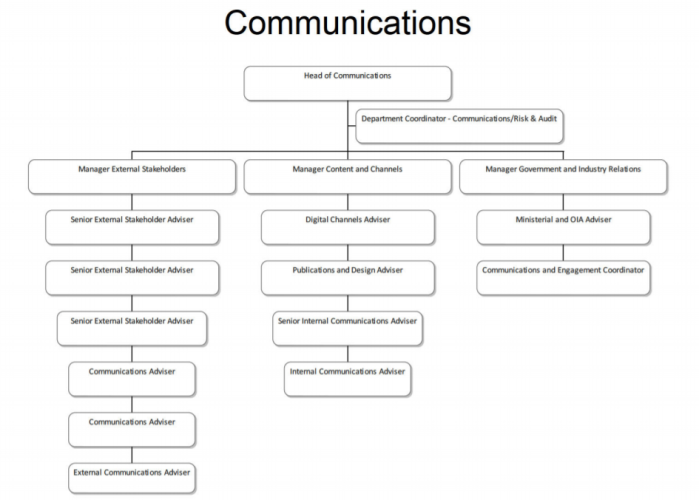

The Bank from time to time sends out newsletters to those signed up to its email list. Yesterday’s one was from one of Orr’s deputy chief executives, the Assistant Governor Simone Robbers (she of the 17 person communications department, among other bits of her domain).

The full text of the email is here. It was sent out under the heading “Our priorities and key progress on our mahi” (“mahi” apparently means work, but whether in Maori it carries a sense of responsibilities or of self-chosen agendas isn’t clear to me). Among the Bank’s self-chosen roles appears to be the campaign to change the name of the country, given the repeated use of “Aotearoa” for New Zealand.

The newsletter isn’t long but it is quite telling.

It begins with this bumpf

While a new ‘normal’ is emerging in New Zealand after the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the pandemic continues to have significant and ongoing consequences across the globe. We are actively engaging with our Central Banking colleagues around the world to share policy advice and insights. As explained in this recent op-ed from Governor Adrian Orr, it is clear from our discussions that the COVID-19 health shock is impacting nations in similar ways, however, the economic and policy impacts differ greatly.

I wrote about that content-lite zone on Monday.

Here in Aotearoa, although we have successfully contained the virus, and many parts of the economy are back up and running, households and businesses face uncertain times and potential further disruption as the full economic impacts of the pandemic become evident.

Name of the country aside, I guess it is unexceptional, but also rather empty. She goes on

We at the Reserve Bank, Te Pūtea Matua, need to keep working together with all of Government and industry, just like we did at the start of the pandemic, to respond to the challenges. We need to be prepared to manage our economic recovery well, while not losing sight of delivering for the long-term interests of all those in Aotearoa.

These “long-term interests” – whatever they are – are simply not something the Reserve Bank has responsibility for. It seems to be cover dreamed up by the Governor to weigh in on anything he chooses.

And that is it on anything even close to the core responsibilities of the Bank. Inflation – let alone inflation expectations – doesn’t get a mention at all. Nor does (un)employment, that the Bank was so keen on talking about last year. Nor, perhaps to no one’s surprise, does the utter failure to have had the banking system positioned for negative interest rates – supposed now to be work in progress, in a highly core area, but no mention here whatever. Instead, we learn what the Bank has been devoting its energies to

Alongside supporting the economy and all New Zealanders by providing liquidity to banks and coordinating monetary and fiscal policy settings, we have also continued to deliver on our commitments including:

- Jointly working with The Treasury to see the new Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bill introduced to Parliament

- Publishing the Statement of Intent (SOI) for 2020-2023 and further embedding our Tāne Mahuta narrative

- Agreeing to a new five-year Funding Agreement to ensure our long term commitments are met

- Progressing our Te Ao Māori strategy through our economic research and proactive outreach to regulated entities, Government and Māori partners

- Working closely with our fellow Council of Financial Regulators (CoFR) members to manage and co-ordinate regulatory work to enable the financial sector to focus on their customers.

During this time, some of our initiatives have received sharper focus as we look to respond to COVID-19 challenges. For example, the financial inclusion issues that are being faced by everyday New Zealanders. We congratulate the banking sector for their leadership in recently becoming the first living wage accredited industry in New Zealand. It is also a good time to deepen our collective understanding of climate change risk in the financial sector, and ensuring we are all taking a long term and sustainable approach to economic recovery and future resilience.

We are using this period to consider what is ahead and what steps we need to take so we can live up to our vision of being ‘A Great Team and Best Central Bank’ and deliver as kaitiaki (caretaker) against the commitments we made in our SOI.

Actually, the Bank doesn’t “coordinate monetary and fiscal settings”: the Minister of Finance sets the Bank a target, and the government sets fiscal policy, and then the Bank (MPC) is just charged with getting on and doing its monetary policy job, given all of that.

But even set that to one side, what do we see prioritised? Well, there is the tree god nonsense that the Governor seems so fond of. Perhaps it does little harm – although as I’ve unpicked it in the past it is often actively misleading – but right up there at number two on the list? Then, of course, we get the Bank’s Maori strategy – something that is not clear is necessary at all (in a wholesale-focused organisation) – or which has generated anything of substance (and no research, despite the claims here) in support of the Bank’s actual statutory responsibilities. But it advances the Governor’s personal whims and preferences I guess.

Then we move off the bullet point list and on to the next paragraph, and even more highly questionable stuff. There is that line about “financial inclusion” which, whatever it means, clearly has nothing whatever to do with the Bank’s twin responsibilities for financial stability and macroeconomic stabilisation. There might be some worthy issues there, at least on some reckonings, but they are nothing to do with the Bank.

Then – and this was the one that caught my eye – there is the weird reference to the banking sector and the so-called “living wage”. I’m sure the Green Party must love that settlement, and whatever deals banks want to sign up to for their staff is really their affair, but what has it to do with a prudential regulator, the Reserve Bank – which is not, repeat, some general regulator of all banking sector activities? I suppose we should be grateful not to see the Bank praising the Kiwibank decision to refuse banking facilities to lawful and creditworthy businesses doing business that the Governor profoundly disapproves of.

But perhaps that is encompassed by the next sentence.

“It is also a good time to deepen our collective understanding of climate change risk in the financial sector”

Not clear why it is a “good time” (one might have supposed a higher priority now might be, for example, understanding the risks to the financial sector from a prolonged downturn and limited monetary policy response, or to have understood better the issues and options around macro-stabilisation and the (current) effective lower bound on nominal interest rates). But, for what it is worth, I think we can pretty easily conclude that the risks of climate change to the New Zealand financial sector are vanishingly small. But acknowledging that might make the Governor’s position – endlessly weighing in on these personal causes – seem more obviously inappropriate.

And who knows what lurks beneath that

ensuring we are all taking a long term and sustainable approach to economic recovery and future resilience

It isn’t even clear whether the “we” is supposed to refer to the Reserve Bank or the rest of us. What is clear is that none of it has anything much to do with the monetary policy responsibilities of the Bank – the bits actually to be able recovery. Full employment, conditioned on price stability, should be what matters, but none of that gets a mention at all.

And then Robbers ends with this

We are using this period to consider what is ahead and what steps we need to take so we can live up to our vision of being ‘A Great Team and Best Central Bank’ and deliver as kaitiaki (caretaker) against the commitments we made in our SOI.

As I noted earlier in the week there was a speech on this topic a month ago. It was startlingly empty, devoid of any real sense of (a) why this goal made sense, (b) how the Bank, and those it works for, might know if it was achieving the goal, or (c) what steps management was taking to deliver on the goal. When he delivered the speech, I noted down a strange comment from the Governor about how it is “therapeutic” to be able to think about these issues. Even at the time it struck me as a luxury most private businesses wouldn’t have, and one one might not expect a central bank grappling with a deep economic downturn, falling inflation expectations, rising unemployment etc to have either, at least if it were doing its job. Then again, the Bank has a big budget and no real accountability so I guess the Governor can simply pursue his whims.

And that is about it.

In a way none of it was that surprising. This is the Reserve Bank that Orr has been creating in his own image: one that simply isn’t doing its job well, doesn’t have its eye on the ball, shows no sign of thinking deeply about the core challenges it should be addressing….all while pursuing the personal ideological agendas of the Governor (and his handpicked senior management – most probably you don’t get or keep a job on the top team – or perhaps further down the organisation either- unless you are all-in with his alternative, non-statutory agenda). We deserve a lot better, the economy needs more, but there is no sign that the Bank’s Board – paid to hold the Governor to account – or the Minister of Finance care. It is just another marker on the journey of the degrading of the capability of our economic institutions, and of the legitimacy and authority of our autonomous central bank.

There was one final thing I noticed deep down the email (which had various links to other bits and pieces). As I’ve noted regularly, the new Monetary Policy Committee has now been in place since 1 April last year. In that entire time, including through some of the bigger macro challenges in modern times, we’ve heard not a word from any of the three external members of the Committee, the ones carefully selected to not be awkward for the Governor, to meet the government’s gender quota, and to exclude – consciously and deliberately – anyone with current monetary policy or macro expertise. But now we have. There is a couple of minute Youtube clip where we see and hear from the externals. Not, of course, that they say anything of substance, anything about actual monetary policy, inflation, employment or anything. But they wax lyrical about a wonderful collegial process, and what a learning opportunity has been – and about how they don’t pay much attention to things for six weeks and then get together, with no undue influence from anyone. No doubt they are all deeply sincere, but it did have a bit of sense of a hostage video, produced to show that the Committee really exists. It should assuage no concerns at all about the structure, the people, the lack of transparency, and the lack of accountability.