Liam Dann, apparently the Reserve Bank’s favoured journalist, has a column on the Herald website on the Governor’s proposal to increase substantially the minimum core capital ratios for locally-incorporated banks. No doubt it will warm the Governor’s heart, if perhaps not the more rigorous of his staff. Dann’s column runs under the rather populist heading “Don’t let Aussie shareholders hijack our banking debate”.

And yet, here’s the thing. Dann advances not a shred of evidence in support of his suggestion. He writes

I also know the Reserve Bank’s new capital ratio proposal is an important topic for national debate.

And it is becoming one-sided.

The sheer weight of PR power pushing for the status quo – ultimately the interests of Australian bank shareholders – is what leaps out at me in this debate.

We’re seeing the screws turned on the Reserve Bank by numerous financial institutions, lobby groups and even opposition politicians, in a way that undermines the process.

“Becoming one-sided” when a well-resourced major economic regulator, able to act as prosecutor, judge and jury in its own case, with no rights of appeals – and able to get media coverage whenever he wants it – proposes very major changes in the operating environment for a core part of our financial system, without robust supporting analysis or a proper cost-benefit assessment, and a wide range of parties push back?

Perhaps Dann didn’t notice that the Bankers’ Association put in a unified submission. Sure, the Australian-owned banks are the biggest members of the Association, but the small New Zealand banks are also members. The Bankers’ Association submission draws on work led by former Secretary of the (New Zealand) Treasury, former (New Zealand) Productivity Commission member, Graham Scott, supported by other analysis undertaken by Glenn Boyle (New Zealand) academic at Canterbury University, Martien Lubberink (a Dutch academic, and former bank regulator, at Victoria University, and one other New Zealand economist. As a reminder, all the bank members of the association (New Zealand, Australian, Chinese, Dutch, British, American) signed on.

What of other economists? I’ve been fairly vocal on the subject, speaking only for myself (and I may be the last native New Zealanders who has no family connections to Australia at all, let alone any connections to Australian-owned banks and their shareholders). My former colleague Ian Harrison has gone into some of the issues in much greater depth. He’s a New Zealander too – driven by his reading of the evidence, argumentation, and the public interest – and didn’t do any of his work with Australian bank shareholders as his focus. I guess we’ll have to wait until the Reserve Bank finally publishes all the submissions to see the full range, but I’ve read several other unpublished submissions by New Zealanders, working for New Zealand firms, that were far from convinced that what the Governor is proposing would be in the New Zealand public interest.

If anything, I have been a little surprised at how quiet the Australian banks have been, at least in public. Presumably there is intense lobbying going on behind the scenes – on both sides of Tasman – but isn’t that entirely appropriate, and what one should expect (and welcome)? Perhaps it would be better still if the debates were played out more openly….but that might require the Governor to actually engage, not to play his “politics of slur” card, that anyone disagreeing with him is simply serving vested interests, in the pocket of Australian banks.

And what of that bizarre suggestion that somehow the “screws are being turned….by Opposition politicians”…. “in a way that undermines the process”. The Opposition must be flattered that anyone thinks they have that much power. But quite what bothers Dann about the Opposition (or the wider opposition) isn’t clear….except perhaps that it has upset that nice Governor, who only has in mind – and is clearly gifted with unique insights on – the wider public interest. Contest and scrutiny and challenge are part of how policy is, and should be, developed and tested.

Anyway, you rather get the gist of the Dann column with this quote

To me, Orr and his predecessor Graeme Wheeler both seem to be intelligent, philosophical thinkers of a kind that is sadly all too rare in the upper levels of the New Zealand political sphere.

or

Neither this Governor nor the last has been troubled by differing views on where interest rates should be or what inflation is doing.

That would be same Governor (Wheeler) who marshalled his entire senior management team to complain formally to one of the banks (he regulated) when that bank’s chief economist criticised Wheeler on monetary policy?

or (of Wheeler)

For some reason many local commentators made assumptions about the Governor being the prickly one.

“For some reason”! Very good, very visible, reasons – whether one was inside or outside the Bank at the time.

In Dann’s world, Wheeler and Orr have been something akin to perfect hero knights, to whom the rest of us should defer in some mix of wonder and gratitude. In the real world, both were pretty deeply flawed, with increasing questions about whether Orr is equipped (eg temperamentally) for the role (it became clear that Wheeler wasn’t).

When half-baked and costly proposals emerge from very poor policy processes – and when there are no appeals against Orr’s unilateral exercise of statutory power – those proposals need to be robustly scrutinised and challenged, by entities directly affected (whichever country they come from), and by those with a concern for the wider health and economic wellbeing of New Zealand. Good proposals always benefit from robust scrutiny (even just enhancing confidence that what looks good actually is) and bad, poorly supported, proposals put forward by the confident and powerful badly need that scrutiny and challenge, in the public interest. There are plenty of serious questions journalists could put to Orr – if he’d give them access to ask them – and, on some at least there might be convincing and robust responses. We’d all be better for hearing how the Governor deals with the substance of disagreement. At present, reliance on slurs raises further questions as to whether the Bank has good answers, and whether it (and the Governor) have thought broadly and deeply enough.

A few weeks ago we learned that the Governor was planning to have some independent experts rather belatedly involved in what has, to now, been a very poor policy process.

The Reserve Bank is also in the process of appointing external experts to independently review the analysis and advice underpinning the proposals.

On the surface that sounded better than nothing, although as I noted in a post just before the FSR

And who are they going to find to serve as “external experts” this late in the piece, when most of those who think about the issues domestically have already either expressed their views and been involved as consultants in preparing submissions by others. There can be a role for overseas experts, but knowledge of the New Zealand system and New Zealand experience should not be irrelevant. And quite what is the selection process the Governor is going to use at this late stage – the suspicion will inevitably be that he will be aiming for people just credible enough to look serious, but emollient enough not to want to make difficulties.

That same day the Bank quietly posted on its website – where no one would find it who wasn’t looking – the terms of reference for these external experts, together with the names/background of the people the Governor had appointed. All three are from overseas, none (it would appear) with much/any background in banking regulation and none with any substantial background in New Zealand economics or banking (one spent a few weeks here in 2014). At least two seem to have publications which suggest they will be very sympathetic to the Governor, and one other has published an entire book on protecting bank supervison from regulatory capture (good book).

You will recall the report last week that at FEC the Governor had gone further and (slanderously) claimed that anyone local had already been “bought” by the banks. Which left me puzzling again at the way the Bank has apparently overlooked Professor Prasanna Gai, at the University of Auckland, of whom we learn.

Professor Gai is currently serving a four-year term on the Advisory Scientific Committee of the European Systemic Risk Board

He might be presumed to have some relevant perspectives and experience, and I hadn’t seem his name associated in public with any other submissions/views on the current capital proposals. I have no idea what his views on bank capital might be, but I suspect he isn’t flavour of the month at 2 The Terrace for some of his other views on the governance of financial stability etc. And, unlike the foreign experts, he would have been somewhat attuned to the local debate.

As it is, in addition to having been carefully selected by the Governor himself – at a late stage in the process, when he already has his stake in the ground – the role of the “independent experts” has been drawn very narrowly. One could even say, generously, surprisingly so.

First, there is the framing in the terms of reference. Thus (emphasis added)

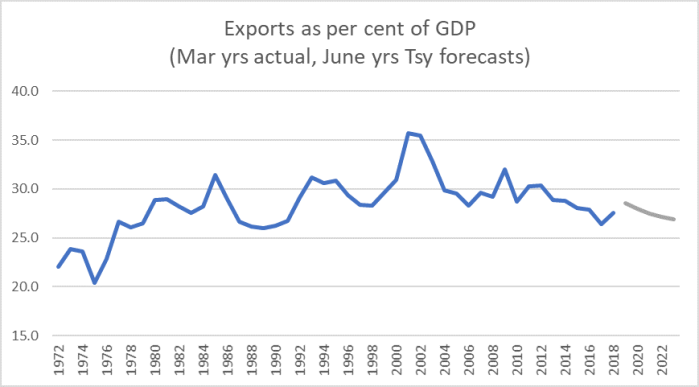

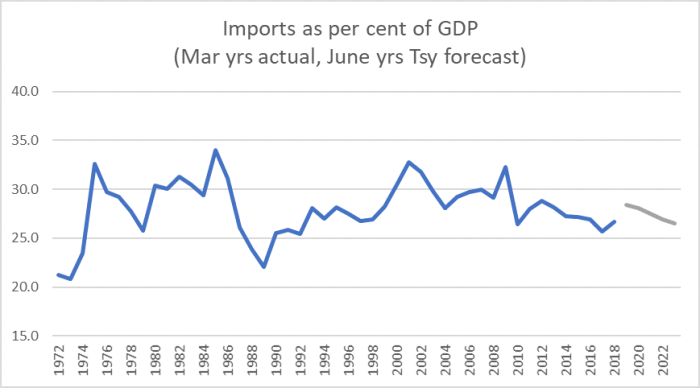

The Capital Review has been carried out within the context of New Zealand as a small open economy, with external imbalances and an economic and financial system that is disproportionately subject to external economic and financial shocks and changes in offshore sentiment

This claim pops up quite regularly from the Bank, but there is no empirical or analytical support offered for it all at all. Then we are told

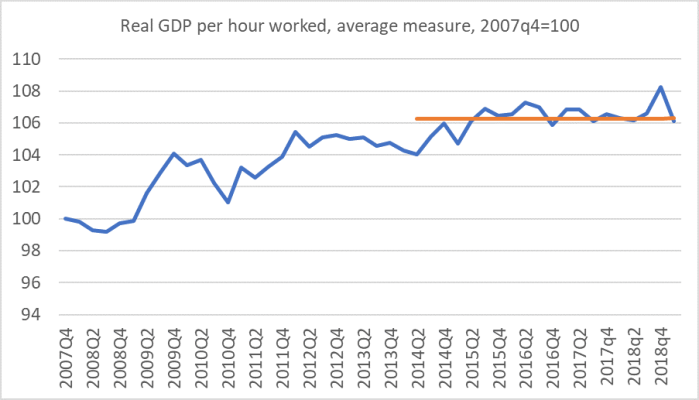

Much of New Zealand’s private debt is concentrated in the household and agricultural sectors, and has been steadily climbing over recent decades.

That second half of that is simply wrong. There were big run-ups in debt (to income or GDP) in the 90s and 00s, but the ratio of private debt to GDP or income is little different now than it was prior to the last recession.

The risk appetite framework is centred on the concept of ensuring that systemically important banks can survive large unexpected losses – i.e. losses that have a likelihood of occurring only once in every 200 years. This is a higher degree of risk aversion than is implicitly built into the New Zealand system at the moment, reflecting the Reserve Bank’s judgement that the economic and social impacts of financial crises are large and more wideranging than previously realised.

And yet have outlined nothing (here or in the fuller documents) in support of the claims in the final sentence, nor do they note – these are overseas experts recall – that New Zealand itself, like Australia, has not had a systemic financial crisis in well over 100 years.

And they repeat one of their starting stipulations

Capital requirements of New Zealand banks should be conservative relative to those of international peers, reflecting the risks inherent in the New Zealand financial system and the Reserve Bank’s regulatory approach.

But it is all castles in the air stuff, because they never seek to demonstrate that the risks around the New Zealand financial system (floating exchange rate, vanilla loan books) are even as high, let alone higher, than those of a typical advanced country.

What also wasn’t clear from the initial Reserve Bank reference is that the focus of the independent experts is not to be on the decision still to be made. Instead, they are invited to review all the papers the Bank has released in its (multi-year) capital review. This is the Scope of Work

The External Experts Report will cover:

- Is the problem that the Capital Review seeking to address well specified?

- Has the Reserve Bank adopted an appropriate approach to evaluate and address the problem? For example, is the range of information considered, and the analytical approach appropriate?

- Do the inputs and cited pieces of evidence used by the Reserve Bank in its approach appropriately capture the relationship between bank capital and financial system soundness and efficiency?

- Has the analysis and advice taken into account all relevant matters, including the costs and benefits of the different options?

- Have the issues raised in submissions been assessed fairly and adequately? The External Experts will only consider the Reserve Bank’s assessment of issues raised in the submissions on the first three consultation papers.

- Have the key risks been adequately considered across the proposals in the Capital Review? Was the advice and analysis underpinning the Capital Review reasonable in the New Zealand-specific context?

The Capital Review has generated internal analysis covering a wide range of issues. This analysis has formed the basis of four public consultation papers and a much larger number of internal reports. This analysis has covered all aspects of the capital requirements, including the definition of capital (“the numerator”), the calculation of risk-weighted assets (“the denominator”) and the capital ratio itself.

Thus, the independent experts are not asked to look at the submissions on the latest (most controversial document). They are invited to consider whether the “advice and analysis” was ‘reasonable in the New Zealand-specific context”, and yet there is almost nothing about the New Zealand specific context in the “how much capital is enough” consultation papers, none of the experts has any material New Zealand specific knowledge, and they are not supposed to engage with or review the submissions. And

It is not expected that the External Experts will carry out extensive consultation as part of their work. Any external consultation should be agreed in advance with the Reserve Bank.

If, for example, one of the experts was somehow to become aware of (say) Ian Harrison’s specific critiques of some of the modelling, they would be prohibited from engaging with Ian without the prior permission of the Reserve Bank.

I’m not impugning the integrity of the independent experts. But they have been chosen by the Governor, having regard to their backgrounds, dispositions, and past research – a different group, with different backgrounds etc, would reach different conclusions – and the Governor is well-known for not encouraging or welcoming debate, challenge or dissent. Quite probably the experts, each working individually, will identify a few things the Bank could have done better, but it will alll be very abstract, ungrounded in the specifics of New Zealand, and the value of their report is seriously undermined in advanced because of who made the appointment, and the point in the process where the appointment was made. This is the sort of panel that, at very least, should have been appointed a year ago. Better still, it would not have been appointed by the Governor.

The flawed process highlights just what is wrong with the governance of banking regulation and related issues in New Zealand. We need an expert bank supervisory body, but that body shouldn’t be able to set big-picture policy all by itself (one unelected individual, to whom all the rest work). Those calls should be made by the Minister of Finance – who, in any case, should be playing a more active and public role on this specific proposals in front of us – advised by both the Reserve Bank and The Treasury, and drawing on whatever independent perspectives the Minister would be useful to the process. The current system would be flawed even if we had a superlative Governor – expert, judicious, rigorous, open-minded, self-critical etc etc – but it is performing particularly poorly under the leadership the Reserve Bank has had for most of this decade, as the Bank has chosen to take to itself bigger and bigger interventionist policy calls.