In my post on Monday I was critical of various aspects of Liam Dann’s Herald pieces in praise of New Zealand’s high rates of immigration. Part of his story was that we simply had to keep on with high rates of immigration or our population would stop growing and……well, there lies dragons, or at very least “economic stagnation” and some existential threat to “New Zealand’s economic and social wellbeing”.

A casual reader might have supposed that there were no examples of countries with flat or falling populations, no straws in the wind we could look at and see how likely it was that a stable or even modestly falling population would represent a serious threat to the living standards (material and otherwise) of New Zealanders.

There was a new wave of Conference Board Total Economy Database data out a couple of weeks ago. It has wider coverage than the OECD databases and the economic estimates are a bit more timely too. I’ve used Conference Board data in numerous posts over the years, with a particular focus on the 40 or so advanced countries (OECD members, EU members, plus Singapore and Taiwan).

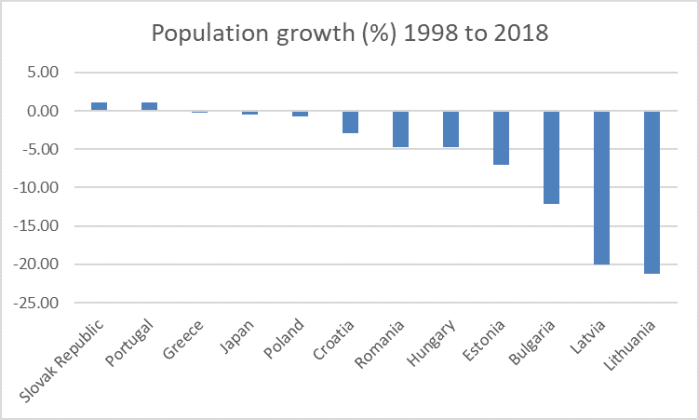

Over the last 20 years, 10 of those countries have experienced a fall in the total population, and another two have had almost no population growth.

If one takes a more recent period – just the current decade – all the countries with falling populations are still falling, and they’ve been joined by Portugal. Spain’s population is also now flat.

Of course, the economic performance of one of these countries – Greece – has been truly atrocious. Real GDP per capita is still about 20 per cent below 2007 levels, and even the average level of labour productivity has fallen. But no one supposes that Greece’s economic woes are because the population is flat or falling: if anything plummeting living standards and high unemployment have prompted Greeks to look for better opportunities elsewhere.

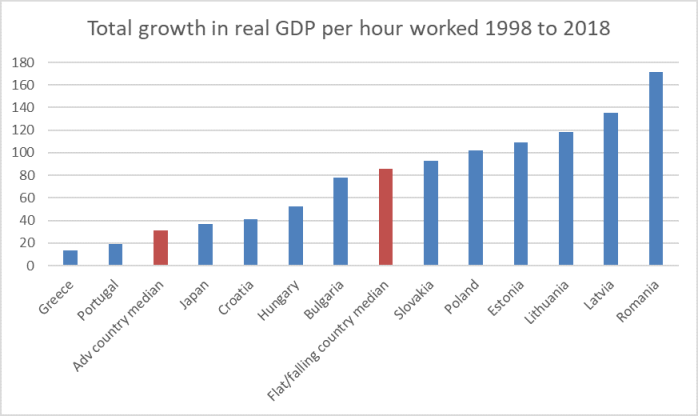

Here is the productivity growth (real GDP per hour worked) performance of those countries with flat or falling populations, again over the 20 years to 2018.

A flat or falling population is, of course, no guarantee of economic success (Greece and Portugal are what they are), but it certainly doesn’t seem to have been a major roadblock in the way of strong economic performance over the last 20 years. Even Japan – already rich 20 years ago, and often a poster-child for the alleged economic problems of a falling population – has had productivity growth outstripping that of the median advanced country.

Where would New Zealand fit in that picture? New Zealand – with rapid population growth – managed 24 per cent productivity growth over 20 years, better than Greece and Portugal, but well below the median, let alone the median of the flat/falling population countries.

20 years ago falling populations really were a new phenomenon. And 20 years ago, many of those countries really were rather poor, just a few years out of Soviet domination. Perhaps one needs to look at more recent periods to really see the (alleged) crippling effects of a flat or falling population? So I had a look at the period from 2007 to 2018 (choosing 2007 so as not to start my comparison in the middle of a severe recession), and over that period the median country with a flat or falling population also did materially better than the median advanced country (or the median of the countries with fast population growth). New Zealand, once again, underperformed each of those medians.

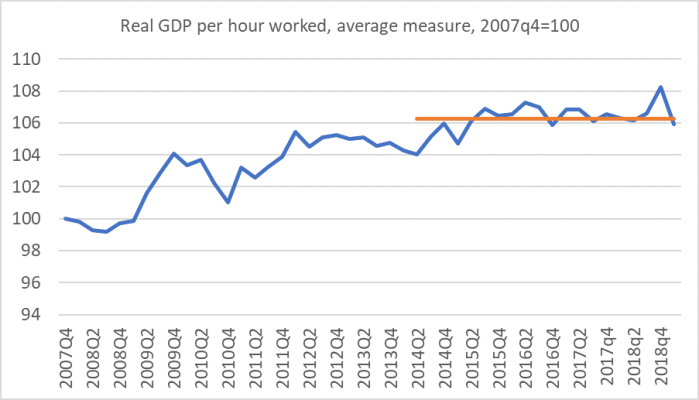

But the focus of Liam Dann’s article had been on the population/immigration surge New Zealand has experienced since 2012. I’m very reluctant to put much weight on short-term comparisons (even across a pool of other countries there can be other cyclical factors that muddy the water), but….what the heck, here it is.

You’ll recall my chart showing an estimate of labour productivity growth in New Zealand.

That was basically no productivity growth over the last five years, and perhaps 1 per cent total productivity growth over the period since 2012.

There are various ways of getting an estimate of labour productivity. Mine (in the chart above) averages the two measures of GDP (production and expenditure) and the two hours measures (HLFS and QES). I’m not sure quite what the Conference Board uses, but their numbers aren’t inconsistent (if perhaps a touch lower) than what is in my chart.

Here is productivity growth for the countries with flat and falling populations from 2012 to 2018, with numbers for New Zealand, all advanced countries, and the median of the flat/falling population countries also shown.

Using slightly different estimates, we might have done better than Portugal but that is as far up the ranking as you can get New Zealand over this period, one when we have – on the Dann telling – been blessed by such a beneficient immigration policy (and associated rapid population growth). Of these countries, Japan and Slovakia already have higher average labour productivity than New Zealand does, while many of the countries are now also close. The convergence story in defence of New Zealand (others are just catching up) has long since lost most of its salience: we were supposed to be one of the countries catching up, but we just haven’t been.

For what it is worth, over this particular recent six year window, New Zealand’s productivity growth was not just second lowest on this chart, but second lowest among all the advanced economies.

My main interest is in New Zealand, an incredibly remote set of islands. Over decades now there has been no sign that rapid policy-driven population growth has been helpful to our medium-term economic performance. But there is no necessary reason why issues that might be relevant to our economic underperformance should also be relevant for countries much closer to major markets, supply chains, networks and opportunities.

On the other hand, there is no sign that countries with flat or falling populations are doing particularly poorly. In fact, in economic terms, most seem to have been doing just fine.

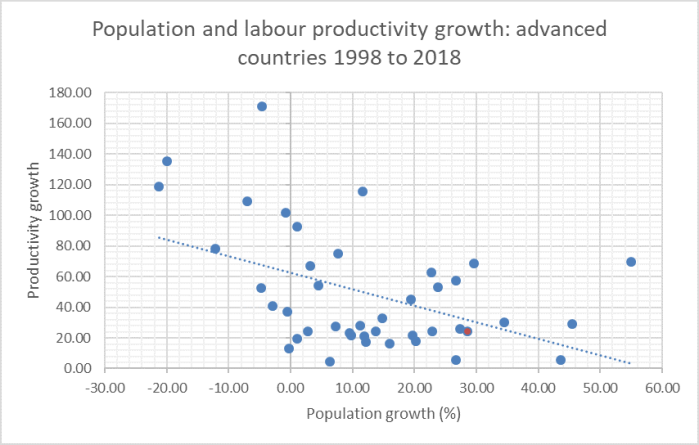

Simple cross-country correlations can always only take one so far. After all, the countries with flat or falling populations will include those where people are fleeing underperformance (Greece say) and countries with rising populations will include some of those where people are attracted to economic success (Singapore say): in neither case is it likely that the main direction of causation runs from population growth to economic success.

But, for what they are worth, here is a scatter plot showing population growth and productivity growth across those 40 or so advanced countries over 1998 to 2018 (one dot per country, New Zealand is red).

It isn’t a tight relationship, but it is there (and was there is the economics literature decades ago) and isn’t obviously skewed by a single outlier country. And New Zealand isn’t an outlier either – our productivity growth over 20 years was only a bit less than one might have expected from this crude relationship.

For the much shorter more-recent period (2012 to 2018), the negative relationship is still there but, as one would expect (with other stuff going on), is weaker. But New Zealand more starkly underperforms. Perhaps that underperformance – little or no productivity growth for years – will eventually be revised away. Perhaps.

I’m not one of those with any generalised aversion to population growth. Most population alarmism, at least at the macro level, is misplaced. Technology, ideas etc keep on allowing for rising material living standards for more people. But equally, there is little evidence that rising populations – beyond some critical low thresholds – themselves work to boost material living standards, and some signs that advanced countries with rapid population growth do less well (in material terms) than countries with less rapid population growth (even with all the sometimes conflicting chains of causation at work).

But across advanced countries as a whole even if all that was simply false, we’d still be left with a picture of New Zealand where policy has fuelled rapid population growth for most of the last 70 years, even as our relative economic performance has kept on declining. Whatever the situation in Japan or Slovakia, there is decent prima facie reason to be intensely sceptical of the alleged economic gains to New Zealanders from continued high policy-induced immigration to this extremely remote corner of the world.

And few/no signs that countries with flat or even falling populations need to worry about economic underperformance stemming from such population changes.

Hello Michael

Your persistence is the face of a bureaucratic and political elite that is largely anti-intellectual is admirable. I figure they have realised that if you ignore critics they eventually move on, which leaves the field to themselves.

Greece is an interesting case as some of their woes are a consequence of a demographic phenomenon often associated with a declining population: population ageing. Since 2000 Greece has one of the oldest populations in the world – currently the four countries with the highest fraction of older people (people older than 65) are Japan (with 26 percent), Italy, Greece, and Germany. Many of Greece’s fiscal issues that helped spark the crisis stem from their pension and retirement policies. Greece has generous state pensions and large incentives to stop working in retirement. This means there need to be high taxes on a small number of working people to pay for the pensions, and if these taxes are not paid when the pension payments are made it means the Government will have large and persistent deficits. There lay the seeds of their crisis.

In contrast, New Zealand has a young population age structure. (This is one of the reasons our fiscal situation looks better than those of many OECD countries.) Our failure to generate decent productivity growth despite this young structure should be an indictment on the country’s economic policies. As you note, when you are small and remote there may not be much incentive for highly productive firms to locate in your neighbourhood, and if their practices are hard to copy it may be difficult to generate high productivity growth. Having some of the world’s highest taxes on business probably doesn’t increase our attractiveness enough to offset the locational disadvantages, although it appears only a minority of people think this may be a factor.

New Zealand is no Greece, but the warning should be taken: population ageing need not be a major economic problem, but can become one if policies are not appropriate. Of course, if Greece had been awake, they will have taken New Zealand’s history as a warning: you will recall Prime Minister Muldoon tried a similar trick to the Greeks in 1976 when he reformed New Zealand Superannuation by lowering the age of eligibility and by increasing the size of the payment, while forgetting to increase taxes to pay for it all. That not only created large deficits and a large debt but it seems to have scarred the nation’s elite into believing that it is important for a country to have low government debt, even though there is precious little economic evidence to support such a theory.

Your list of countries with falling population largely comprise former eastern European countries, and while their progress has been outstanding in the last two decades, few yet have per capita incomes at the very top of the pile. For some of them outward migration must have been significant.

On a less pleasant note, some of the strongest growth in per capita incomes in the medieval period occurred when the Black Death wiped out a third of the population.

Andrew

LikeLiked by 2 people

THanks Andrew

Re your last point, yes indeed. The key resource – other than labour – then was the fixed stock of natural resources. It might be an interesting thought experiment to wonder which countries today would experience a material rise in per capita GDP if a third of the population suddenly died. I’d say (eg) Australia, Norway, S Arabia, Oman, Trinidad, Chile and NZ too. On the other hand, in most of Europe any effect would be small, and quite possibly negative.

Of course, we should neither welcome plagues nor regret native choices to have sufficient children that the population rises. But immigration (not emigration these days) is a discretionary policy choice.

LikeLike

My wife who thinks deeply but does not complain a lot, wonders if that the apparent increased activity of the far right in NZ is the result of the vastly increased volume of immigrants and our inability to keep up with infrastructure and to assimilate cultures alien to our own. She also notes mini ghettoisation in some suburbs in Auckland.

LikeLike

It is a plausible hypothesis, altho I’m not sure what evidence there is of “increased activity of the far right in NZ”. Perhaps it is there, but I wonder what indicators would people point to to demonstrate it?

LikeLike

Increased activity of the far right probably means discussion of the motivation of the Christchurch terrorist. It would seem that NZ was chosen because it is a country with minimal violent ethnic conflicts (unlike much of Europe and the USA). The nearest we have to a ‘populist’ party is NZF and unlike populist parties in most European countries their support has been decreasing ever since they attained power.

LikeLike

An Australian nutter acting alone commits mass murder and that apparently for some, is evidence of “increased activity of the far right.” Or a few years ago there may have been some far right students at Auckland University, according to someone. The “Far Right” fear is politically stirred and based on very thin evidence. There have been a few Nazi idiots in NZ since the 1970’s but no evidence that I’ve seen indicates they are growing in number and threat. The criminal gangs like Headhunters and Mongrel Mob would rank as a bigger threat to the country,

LikeLiked by 1 person

My thinking Michael is that NZ’s high immigration rate is a poor policy response to skills shortage resulting from our high emigration rate. In particular that over 600,000 kiwis have migrated to Australia in recent decades. This doesn’t exactly fit your narrative Michael because Kiwis are not migrating to the main continents, kiwis are migrating across the ditch to cities like Brisbane, which is pretty much just as isolated and distant from the rest of the world as NZ cities are.

Why does NZ have such a high emigration rate?

Probably because our towns and cities, where 85% of us live, have broken housing and transport markets -which is impairing productivity gains. Housing and transport cost increases for the median household have consumed most of the median household income gains for several decades -in particular in Auckland with housing.

Accountancy firm PwC recent report -‘Competitive Cities: A Decade of Shifting Fortunes’ written by chief economist Geoff Cooper has some quantitative data on this. Basically most of NZ has much worse housing conditions compared to Australian cities like Brisbane that are attractive for migrant kiwis. The one NZ city -Christchurch with comparable housing costs -has the worst transport cost increases -meaning half the increase in Christchurch’s disposable income is being spent on increased transport costs.

Obviously many kiwis decide they will not put up with these poor disposable income conditions and migrate to Oz for a better return from their labour market skills.

The PwC report (with a link) is discussed in my below report about free car parking not being a solution to Christchurch’s transport woes.

View at Medium.com

In my car parking article there is also a link to my ‘Housing Productivity Story’ article which I have previously provided to this website. The ‘Housing Productivity Story’ article discusses the theoretical economic model developed by Moretti linking inelastic housing markets with poor productivity.

LikeLike

Re your first para, Aus just has an enormous quantity of natural resources (relative to the number of people) – and have been willing to take in poor relations from NZ. People flow where the better opportunities are for themselves and their families. In our case, Aus has filled the bill – open, richer, relatively close – but of course Aus productivity lags well behind the OECD leading group.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There has been some interesting debate on Australias immigration on Skynews over the last couple of weeks.

The politicians do not want to confront the major issues arising from high immigration .

Of further concern is the policy floated by Labor to allow more family reunification if elected .It appears this could see 100,000 eligible to join family in Aus but it may be more like 200,000 plus according to some commentators.

LikeLike

Probably because our towns and cities, where 85% of us live, have broken housing and transport markets -which is impairing productivity gains.

………..

Does that make sense Michael. Sounds like word salad to me?

LikeLike

Who needs silly old productivity, when you can just keep on farming iron, coal, houses, and overseas students? Hard to believe, but Big Australia just dodged a population bullet. Morrison went to the May election with an insane 270K net migration, second highest of all time. Shorten saw him and raised him, with an even more insane open-ended parent visa scheme. Makes Jacinda look good.

LikeLike

Your statisitics and argument appear solid. I will forward a link to the editor of the NZ Herald and my MP.

To be contrary I expect similar figures for NZ 1860 to 1900 would show a different story with population, productivity and wealth all flourishing. Then there were opportunities to exploit resources: undeveloped arable land, timber and gold and with technology the frozen meat trade. If GGS’s rocket lab was launching rockets hourly and receiving minerals mined on asteroids in return then the possibility of another massive NZ boom of population and wealth could be envisaged.

My family’s roots were in British Railways so I am well aware that managing a decline is much more difficult than growth. Without immigration boosting NZ population what would our politicans and bureaucrats actually do? No new art centres and motorways to discuss, design and open.

I would prefer NZ to be as it was when I arrived rather than the dash to be a miniature copy of Sydney/Manila/Tokyo but if it it does continue to grow at 2% per annum then in 100 years NZ will have a population of 36 million (at least it may be able to feedthem). And maybe then the grandchildren of our current govt will finally face the issue of stopping population growth.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So far the arguments around promoting population growth seem to be based entirely on perceived economic benefits. That’s a valid parameter to use, but let’s not ignore the other factors or benefits that might come from stable population, where the birth rate plus any immigration equals the death rate. That sort of fits with the “sustainability” mantra popular a few years ago.

I’m reminded of Bhutan’s goal of “Gross National Happiness” as an alternative to a GDP measure (guaranteed to give an economist heart burn). They just like staying the way they are. They might be on to something there.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I fear future wellbeing budgets will be used to sidestep the lack of value we get with our immigration policy.

This article explains how NZ is poor at both attracting and retaining skilled (that is the word ‘skilled’ as common usage not the Tourist guides, Bakers and so called Chefs that are ‘skilled’ according to INZ). It only reinforces my opinion that immigration policy in NZ is a plot to maintain a pool of docile low waged workers.

https://www.maxim.org.nz/making-new-zealand-sexy/

Quotes “”New Zealand ranked 17th in the world in its ability to attract talent “”

and

“” While Norway is slightly worse than us at attracting talent (20th place), they are 4th in the world at retaining talent; whereas we’re struggling down at 31st on the list. Our main problem isn’t getting people to migrate here, but we’re apparently doing a terrible job at convincing them to stay. “”

LikeLike