When I opened the newspaper this morning and found the headline “The world needs ethical leadership”, above a column written by someone whose own leadership often fell well short of that standard, it was tempting to go chasing hares.

But I’m more interested in the damage the current leadership of the Reserve Bank is doing both to the standing of the Bank as an institution and – more concerning still – to the New Zealand economy and private firms operating in it, by the Governor’s plans to require banks to raise a great deal more equity capital to support their current levels of business. This morning I want to comment on a couple of contributions to that debate from two of my former Reserve Bank colleagues.

Before doing so, note that I hardly ever agree with the newspaper columns of Business New Zealand’s head Kirk Hope, but his column today on the bank capital proposals is right on point. He ends with suggestion that really should be uncontroversial

BusinessNZ recommends that the Reserve Bank should undertake a comprehensive cost/benefit analysis of the proposals before any further steps are taken.

In fact, the Reserve Bank tells us repeatedly it only intends to do such an exercise when it is too late for it to inform any public discussion or submissions – it will support whatever whim the Governor finally runs with, rather than assisting the development of policy and the contest of evidence and arguments around the proposals the Governor is hawking, and which the Governor himself will get to decide on.

It has been a quiet week in central Wellington, with many people taking the chance to use a few days’ leave to get quite a long autumn break. Nonetheless, a fairly good crowd turned up at Victoria University at lunchtime on Wednesday to hear Ian Harrison critically review the Reserve Bank’s capital proposals. Ian spent most of his career at the Reserve Bank, and did much of the modelling work associated with the previous review of capital requirements, undertaken only seven or eight years ago. Since leaving the Bank he has also consulted for commercial banks on risk modelling and associated capital issues.

I’ve already written here about Ian’s March paper reviewing the Bank’s proposals. Since that paper was written the Reserve Bank has published another 50 page paper attempting to buttress their case, and Ian’s latest presentation – also titled “The 30 billion dollar whim” (with no question mark) – attempted to take account of that paper. He has a further review paper coming; one hopes in time to inform submissions before the Reserve Bank’s deadline on 17 May.

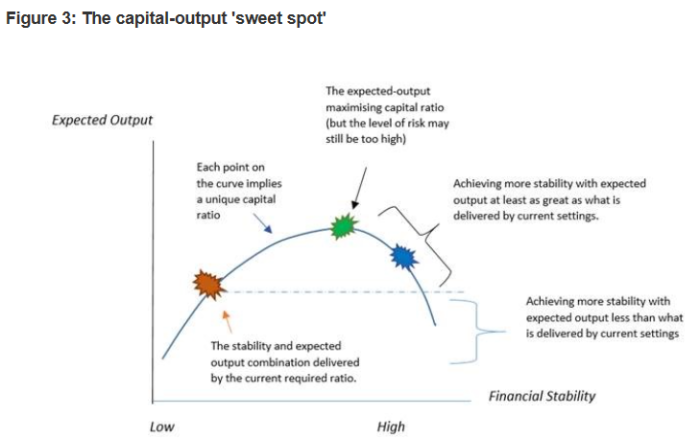

The Bank’s claim all along has been that these proposals are a win-win. We can have a more stable banking system – despite never having had a systemic banking crisis (at least outside an immediate post-liberalisation period) – and higher (expected) GDP as well. This is one of their charts.

It has never really rung true, and none of what they keep on releasing really buttresses their case. As I’ve noted previously, in his speech in February the Deputy Governor acknowledged that the proposals could cut the level of GDP by “up to 0.3 per cent” (say, 0.25 per cent then), and to pay that insurance premium each and every year, on a policy which could be cancelled at any time on the whim of some future Governor, it would have to save us from something truly devastating perhaps 75 years hence. Countries with floating exchange rate, reasonable institutions, and governments that keep out of credit allocation, simply don’t have those sorts of truly devastating events. As I and others (including a rather more prominent US author) have noted, in the serious recession of 2008/09, the (floating exchange rate) countries that had financial crises didn’t perform materially worse than countries that did not. Most likely, what the Reserve Bank is proposing won’t move us north-east of the orange dot (as the Bank claims), but more likely south-east. We’ll be poorer but the banks – already a stable core of (what the Bank tells us every six months is) a stable financial system – will be sounder still. It doesn’t seem like much of a deal…….especially without a robust cost-benefit analysis that we can properly review, or any open engagement with the criticisms various people have advanced.

Ian Harrison also points out that the Bank appears not to have take explicit account of the fact that our main banks are foreign-owned. As he notes, most of the international modelling on capital works on the assumption that banks are largely domestically-owned. If higher capital requirements mean higher total equity returns to shareholders that in itself isn’t a loss to the domestic economy – just a transfer from one lots of nationals to another. There might still be some cost in the form of lost output, resulting from a higher economywide cost of finance and wider intermediation spreads (eg the Deputy Governor’s “up to 0.3 per cent”). But in New Zealand, if we compel banks to have much more capital to support their level of business, and there is no full offset between the cost of debt and the cost of equity (and the Reserve Bank accepts there won’t be), there is an expected net transfer from New Zealanders to (in this case) Australia and Australians. That is where Ian’s $30 billion number (a present value calculation) comes from. It doesn’t figure in any of the Reserve Bank documents, which seems on the face of it a rather gaping omission – especially from a Governor who appears to have a strong prejudice against Australian banks.

There was a lot of material in Ian’s presentation and I can’t cover it all here. But a few other highlights:

The Bank likes to claim that their new approach – specifically identifying how infrequently they think New Zealand should expose itself to a financial crisis (once in 200 years is the Governor’s stab in the dark) – is a significant step forward, and determines the proposed capital ratios that emerge from the analysis. Ian notes that, if anything, it appears to be the other way round: they initially used a 1 in 100 year framing, found that produced results they didn’t much like (something like current capital requirements), and with no supporting analysis at all – there is a single sentence footnote – switched to the 1 in 200 year framing. Support rather than illumination springs to mind. The Governor seems to have wanted high headline minimum capital ratios – regardless of cost, regardless of the fact that the way ours will be calculated will be more demanding – and to have cast around for anything to prop up such a case.

In his rather whimsical vein, Ian goes on to suggest that there is so little substance behind the proposal that perhaps the proposed 16 per cent minimum capital ratios (CET1) for big banks might as robustly have been derived from the Governor’s fling with the tree god Tane Mahuta: the kauri tree of that name has a girth of 15.44 metres apparently, and allowing a little for growth we get 16. In a similar vein, he goes on to note that kauri trees are (apparently) bigger than gum trees, which perhaps accounts for the Governor pushing his requirements well beyond those in Australia.

Ian unpicks the relevance of various of the overseas paper the Bank cites, including noting how dependent any of the results are on specific assumptions, specific sample periods (especially around loan losses – using a short period centred on 2008/09 will produce different results than, say, using the last 100 years). In some of the Bank’s New Zealand analysis (including around the late 80s/early 90s) instea of using loan write-offs (recorded just once, when the write off occurs) they’ve used average annual non-performing loan data – even though the same non-performing loan can remain on the books for several years, but can only be written off once.

He noted briefly, as I have at more length here, the important distinction between (a) marginal effects and average effects (we should only focus on what further reduction in crisis probability this further big increase in capital requirements will result in), and (b) between the costs of the bad lending and investment choices that led to loan losses, and the cost of bank failures themselves (the Reserve Bank simply never addresses this latter point).

In passing he notes that references to reducing fiscal costs of bank failures tend to be overstated: the common reference point in 2008/09, and yet bank capital ratios are already materially higher than they were then, and even in 2008/09 the net fiscal costs (after recoveries and sales) were often quite small. Oh, and OBR here is supposed to further reduce, or eliminate, fiscal costs.

In its latest document, the Bank devoted a lot of space to the alleged social costs (suicides, divorces, mental health problems) etc of financial crises. Ian looked at all their references, and I don’t think it would be going too far to say that the Bank’s representations were borderline dishonest – often drawing from countries without a decent social safety net (or countries without the buffer of a floating exchange rate). Again, the idea that the Bank was looking for support rather than illumination sprang to mind.

Ian ended his presentation with a simple insurance parallel, suggesting (as above) that the Bank was inviting New Zealanders to buy (well, perhaps compelling us to buy) a very expensive insurance policy of the sort no rational agent would ever buy voluntarily. All backed up with inadequate analysis and no serious engagement.

After Ian’s presentation there were several thoughtful questions from the floor. Graham Scott, former Secretary to the Treasury back in the reform era and currently a member of the Productivity Commission – a “dry” if ever there was one – asked about the assumptions around the Modigliani-Miller proposition. At the extreme, this proposition asserts that the financing structure of a firm (mix between debt and equity) doesn’t affect the value of a firm. In this case, for example, requiring banks to hold even a 20 per cent capital ratio wouldn’t affect the economics of banking (required rates of return on equity, and debt costs) would fall to fully offset the increased equity component. It would suit the Reserve Bank case to be able to argue that there is such a full offset, but they don’t. Instead, they assume something like a 50 per cent offset (thus, over time required rates of return on banking in New Zealand will fall, but not enough to fully reflect the reduction in the expected future variance of earnings).

Graham Scott’s point – which echoes one I’ve alluded to here on a couple of occasions – is that the 50 per cent offset assumption may still be too high. He notes that the big Australian banks’ New Zealand subsidiaries are not listed entities. From a shareholder (in the parent) perspective the operating subsidiaries here are little more than another operating division of a much bigger company. Every manager in every operating division will always be looking for excuses to deliver low rates of return (circumstances, regulatory factors or whatever) while still collecting their bonuses and we might be sceptical that the parents will accept low rates of return on bank business here simply because our Reserve Bank says they have to hold more capital. Correlations also matter – reduced variance in New Zealand earnings, might do little to reduce the variance of the earnings of the parent.

I suspect that the direction of the effect Graham Scott points to is correct, but that the effects might be seen in a rather disruptive way. As I’ve noted previously, the Bank’s capital requirements apply only to locally incorporated banks. Big corporates will have no particular problem getting credit from overseas banks that aren’t incorporated here. These might include the parent (Australian) banks, all of which also have branches here, or any other significant bank in the world (Fonterra is most unlikely to pay a higher cost of debt because of regulatory stuff our Reserve Bank does). The bond market also offers a mechanism to take locally-incorporated banks out of the mix – not just for big corporates, but potentially for securitised home mortgages. Some credits can’t be easily or quickly securitised and they are likely to be the ones who bear the brunt of the changes. Overall, credit may be harder to get and more expensive. The other group who may bear the brunt will be depositors – borrowers can over time change their credit provider, but retail depositors (in aggregate) have fewer options (eg overseas branch banks can’t take significant retail deposits).

But none of this – not a single strand of it – is analysed in any of the material the Reserve Bank has put out. Nothing about transitions, nothing really about steady states, nothing about how the fact that the requirements will fall on some but not others will affect the future structure of the financial system. It is really inexcusably poor policy development and communication. One business figure put it to me recently that there is a risk that the Bank’s proposal will actually reduce the soundness of the financial system – increasing the soundness of the core banks themselves (perhaps, unless the parents choose to partly liquidate their exposures, and we are left with banks without strong parents), but reducing the significance of those core banks (and leaving many credit exposures less transparent than they are now). I’m not sure I would yet go that far, but the rather limited and mechanistic approach the Reserve Bank is taking is leading them to overstate even any possible soundness gains, even as they ignore the likely output costs.

It simply isn’t a standard of policymaking we should accept. The Minister of Finance and The Treasury – if the latter isn’t distracted playing sun-moon cards and talking about their feelings – should be demanding better.

And that is more or less the theme of another former Reserve Bank regulator, Geof Mortlock, in his piece on interest.co.nz earlier in the week. After noting how resilient the Reserve Bank’s own stress tests suggest the New Zealand banking system is, and noting some of the likely costs and disruption, Geof notes

One would think that these costs and other adverse impacts would have received a great deal of attention by the Reserve Bank in undertaking a cost/benefit assessment of the proposals. But no. By their own admission, they have not yet undertaken a comprehensive cost/benefit analysis. (Perhaps Adrian Orr was too busy engaging in god-to-god dialogue with Tane Mahuta and the forest fairies to give serious policy matters his attention! Deities are so busy of course.)

I don’t agree with all Geof has to say – he is much more optimistic about the value supervisors can bring to the table than I am – but on the lack of proper, searching, evaluation and robust ex ante cost-benefit analysis we are at one. As Geof says, it just isn’t good enough.

Geof’s bottom line is this

What is needed is an in-depth independent, professional assessment of the Reserve Bank’s capital proposals. Treasury will no doubt review the Reserve Bank’s cost/benefit assessment once the Regulatory Impact Statement has been prepared. However, that is too late in the policy formulation stage. Moreover, with all due respect to Treasury, it lacks the depth of knowledge needed for a rigorous assessment of the different policy options and the costs and benefits of each. What is needed is for Treasury, at the direction of Grant Robertson, to engage a couple of independent professionals (such as an academic specialised in bank regulation and a recently retired foreign senior bank regulator – e.g. John Laker, former Chairman of APRA) to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the Reserve Bank proposals, plus alternative options. The findings of this assessment should be incorporated into the Treasury’s own review and the results be made public. The independent review would considerably assist the quality of the process of assessing the Reserve Bank’s proposals and may assist in reaching a more sensible outcome.

An independent review would sensibly include consideration of:

- the magnitude of economic shock needed to cause any of the large banks in New Zealand to fail, and the probability of such a shock occurring;

- the level of capital needed to enable banks to survive a plausible range of severe economic shocks;

- the composition of capital requirements and other loss absorption facilities that would be suitable to enable banks to survive severe economic shocks, including whether (as in many countries) a substantial proportion could be in the form of debt instruments that convert to equity upon defined breaches of core equity capital ratios;

- the impact of the proposed increase in capital ratios on bank lending, interest rates, property prices and economic growth (with implications for government revenue);

- the impact of the proposed increase in capital ratios on banking system contestability, competitiveness and financial inclusion (especially for those on low incomes);

- the alternative policy options for strengthening the resilience of the banking system, including strengthening Reserve Bank supervision of banks’ governance, risk management practices, lending policies, and recovery planning;

- the bank failure resolution options that could be applied to maintain financial stability with minimal taxpayer risk (and hence reduce the need for high capital ratios).

The Minister of Finance and Treasury need to give serious attention to these matters. And the sooner the better.

I have a lot of sympathy with that. If the Reserve Bank’s supine Board had been doing its job they would have strongly urged the Governor to take such a path – and/or prior open consultation before the Governor himself took a view – from the start. It is all the more pressing that things be done properly, evaluated rigorously, contested vigorously, when it is the Governor personally who is championing these (extreme) changes and the Governor personally who will finally make the decision (with no rights of appeal or review).

As a final note, generally I don’t think the banks help themselves. On both sides of the Tasman banks are typically scared of being openly critical of their regulator. I can understand that to some extent – regulators exercise a lot (too much) power on a lot of dimensions – and no doubt the banks will raise significant concerns in their own submissions. But by the time the submissions are in – and especially by the time the public ever see those submissions – it will be too late to marshall a wider pool of support for their case. Sure, banks are not naturally particularly sympathetic entities, but this is one of those cases where what is bad for banks is probably bad for New Zealanders and the New Zealand economy as a whole. Sadly, banks have made no effort to engage in any public debate on these issues over the 4+ months this Reserve Bank proposal has been in the public domain.

To your last point, I think that Orr has been masterful in discrediting nay sayers before they have even had the opportunity to open their mouths. Anyone associated with the banks has and with an opposing view to RBNZ has often been labelled a lobbyist in the media. Indeed, Orr himself in an interview labelled some who disagree as “just a couple of bloggers” (yourself included?).

On watching some of the frustrated reactions of one or two in the room when Ian Harrison spoke against the evidence provided by RBNZ in support of proposals, I wonder if RBNZ is unduly creating anxiety among members of the public for whom the technical nature of capital requirements is inaccessible – both by omission and in the lengths they are going to to get this proposal across the line.

In terms of an insurance policy, the proposal does not remove the implicit guarantee from government. It also does not inquire as to how much responsibility Government should have and how much responsibility bank shareholders should have. Government receives 28% of bank profits. I think it is fair to at the very least, discuss to what extent government should be involved if an extreme event in the banking system were to occur.

As one alternative (or compliment of the proposal), I would like to see a costing of an explicit crown guarantee, where the crown could then be fairly compensated for said guarantee. Geof Mortlock wrote a piece a few months back where he suggested 5bps or thereabouts might be achieve this – considerably less than 20-40 as claimed by RBNZ for the current proposal.

LikeLike

I’m sure both Geof and I are caught with the broad ambit of Adrian’s “couple of bloggers” (loosely defined).

I’ve also been on record for some time in favour of explicit deposit insurance (although not an overall crown guarantee of all creditors). Of course, proper economic pricing would depend on the level of capital (relative to risk-weighted assets), but at current capital levels for the big banks I suspect a fair price would be more than 5bps. Of course, such a fee is a pure transfer (from one lot of NZers to others).

I think Adrian’s spin may work with some of the general public, but I doubt it really works with even moderately informed people. You are right to suggest banks are easily portrayed as self-interested – so is anyone lobbying against excessively costly regulatory proposals for their industry – so the focus should be on getting arguments, evidence, models etc out there, enabling their material to be scrutinised and challenged. In the same way, bureaucrats have incentives, which aren’t necessarily the public good, and we should expect to be able to scrutinise their claims, and cost-benefit analysis, in depth.

LikeLike

Re the RBNZ’s use of average annual non-performing loans instead of loan write-offs: the error is even larger than the fact that the same loan may feature as non-performing for several years but is written off only once. If the bank reports the loan as non-performing but does not write it off immediately, that is because they consider there is still a realistic chance of getting their money back. Some of the time, at least, they will be right, in whole or in part. So a loan which is reported as non-performing for 3 years and from which (during that time and on final recovery) half the debt is recovered will contribute some 6 times as much to the non-performing loan figures as it does to the loan write-offs.

For year-to-year investment and regulatory decisions, the bank’s conservative and timely estimate of what loans are at risk is an important piece of data; the actual loan write-offs come too late to be really useful. But when doing research on historical data and averaging over decades, there is absolutely no excuse for using the non-performing loan data instead of write-offs as a measure of the cost of defaults.

LikeLike