Presbyterian Support Northern is hosting a series of lectures on different aspects relevant to the wellbeing of children. The first lectures were given by Australian Labor MP, and former economics professor, Andrew Leigh. I wrote about his lectures here.

I was asked to speak on something around productivity and the wellbeing of children (thus there are huge areas highly relevant to child wellbeing that I simply don’t touch on). This was how my talk opened.

Imagine a country in which the average age at death was only about 45, 6 per cent of children died before their first birthday, and another 1.5 per cent before they turned five. Not many children are vaccinated.

Most kids get to primary school – in fact it is compulsory – but only a minority attend secondary school. By age 15 not much more than 15 per cent of young people are still at school. Only a handful do any post-secondary education (total university numbers are about 1 per cent of those in primary school). Houses are typically small – not much dedicated space for doing homework – even though families are bigger than we are used to. Perhaps one in ten households has a telephone and despite the street lights in the central cities most people don’t have electricity at home.

Tuberculosis is a significant risk (accounting for seven per cent of all deaths). Coal fires – the main means of heating and of fuel for cooking – mean that air quality in the cities is pretty dreadful, perhaps especially on still winter days. Deaths from bronchitis far exceed what we now see in advanced countries. There isn’t much traffic-related pollution though – few cars, so people mostly walk or take the tram. The biggest city is finally about to get a proper sewerage system, but most people outside the cities have nothing of the sort. And washing clothes is done largely by hand – imagine coping with those larger families.

Maternal mortality rates have fallen a lot but are still ten times those in 2018 in advanced countries. One in every 50 female deaths is from childbirth-related conditions – which leaves some kids without mothers almost from the start.

Welfare assistance against the vagaries of life is patchy. Most people don’t live long enough to be eligible for a mean-tested age pension. Orphans aren’t in a great position either, and there is nothing systematic for those who are seriously disabled. There is a semi-public hospital system, but most medical costs fall on individuals and families, and there just isn’t much that can be done about many conditions.

There are public holidays, and school holidays, but no annual leave entitlements. No doubt the comfortably-off take the occasional holiday away from home, but most don’t, because most can’t (afford it). Only recently has a rail route between the two largest cities been opened – but it takes 20 hours for cities only 400 miles apart.

I wouldn’t choose to live in that country. Would you?

And yet my grandparents did live there – they were all kids then. This was New Zealand 100 years or so ago, just prior to World War One. I took most of that data from the 1913 New Zealand Official Yearbook.

And if it all sounds pretty bleak, New Zealand was probably the wealthiest place, with best material living standards, of any country on earth. In the decade leading up to World War One, New Zealand’s per capita income was (on average) the highest in the world (jostling with Australia and the US, with the UK a bit further behind). The historical GDP estimates are inevitably a bit imprecise, but on statistic after statistic in that 1913 Yearbook, New Zealand showed up better than the other rich countries the compilers had data for.

The difference in material living standards between then and now is productivity – the new ideas, new products, new ways of doing old stuff, making more from what we have. Of other influences on material wellbeing, the terms of trade haven’t changed much taken over 100 years as a whole, and people work a shorter proportion of their lives now (whether in the market or in the home) than they did in 1913. Then, most (who survived infancy) were in work by 14, and dead by 65. Productivity is that enormous difference between what we enjoy today, and what my grandparent had as kids in middle-class New Zealand families on the eve of World War One.

And yet, by international standards we’ve done badly. We’ve gone from top of class to perhaps 30th today. It would take a two-thirds lift in average productivity for us to match today’s top-tier (a bunch of – small and large – northern European countries, and the United States).

That’s bad. On the other hand, think of the possibilities it leaves open. We don’t need to blaze trails at the productivity frontiers: making significant inroads on the gap between us and the top-tier would make a big difference to us, and to our kids. And economic failure tends to fall most heavily on those at the bottom, so getting a significant lift in productivity opens up possibilities for everyone, including the disadvantaged.

In this address I’m not focused on the how – the specific policies that might make a real difference. My focus is on highlighting the difference that could be made, and calling for our leaders – political and bureaucratic – to start acting as if they believe things can be better, getting in train processes that might identify what is really important for productivity here in New Zealand, and then getting on with it. Despite occasional references in speeches, our political leaders seem to have more or less given up, focusing on other stuff.

There is a (valuable) place for redistribution and policies that address immediate needs now – it isn’t an either/or – but just as no possible redistributive policies in 1913 could possibly have given people today’s material living standards, so any new redistributive policies now will inevitably make much less difference than markedly lifting our productivity performace would. I’ve banged on here about how dismal productivity growth in New Zealand has been in the last five years in particular (a total of 1.5 per cent). The best-performing OECD countries over the most recent five years were averaging more than 2 per cent productivity growth per annum – and all of them were countries catching up with the most productive economies, just as we once aspired to do. If we’d managed 2 per cent productivity growth per annum in the last five years, per capita GDP would be around $5000 per head higher (per man, woman, and child) today.

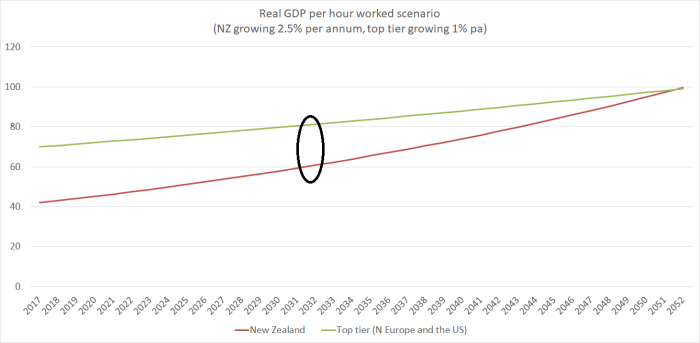

Catching up to the top tier will, in a phrase from Nietzche, take a “long obedience in the same direction” – setting a course and sticking to it. But here is a scenario in which the top tier countries achieve 1 per cent average annual productivity growth, and we manage 2.5 per cent average annual productivity growth. Here’s what that scenario looks like:

I’ve marked the point, 15 years or so hence, where the gap would have closed by half.

Could it be done? Well, on OECD numbers the G7 countries as a group have managed average productivity growth in the last 15 years of about 1.1 per cent per annum, and plenty of OECD countries – each in catch-up mode (Korea, Turkey, and various eastern and central European countries) – have matched or exceeded 2.5 per cent annual productivity growth over that period as a whole. Mine is just a scenario, but it doesn’t look like one that should be beyond New Zealand – and unlike any of those other countries, we were the richest and most productive country in the world barely more than a century ago.

The full text of my address is here. It includes a plug for fixing the manifest evil – by outcome if not by intent – that is our housing and urban land market, which systematically skews away from those at the margins, where (inter alia) our particularly disadvantaged children are typically found.

I end this way:

Judging by the inaction of our leaders in tackling the persistent productivity failure, it suggests that when it comes to crunch ours (regardless of party) care much less about the kids – of this generation and the next – than the cheap rhetoric of election campaigns might suggest. Giving up on productivity – in practice, and whatever the rhetoric – is a betrayal of our kids (and their kids). And most especially it betrays the children towards the bottom of the socioeconomic scales, those who typically end up paying the most severe price of economic and social failure.

Productivity isn’t just some abstract plaything of economists. It makes a real and tangible difference, opening up whole new possibilities and options. We need, and should able to achieve, a whole lot more of it. Our kids deserve no less.

Once again, Michael, you are spot on!

LikeLike

We are all clear on the issue of productivity. Micheal as hammered it into most of us readers. But as yet his only solution offered is dropping the immigration target to 15k to 50k. But successive governments including NZFirst and Labour have not done it when they have the power now to do so.

The reason is that our industries have changed to mainly primary industries, tourism, international students and services. With 10 million cows, 30 million sheep and 1 million deer and goats we have reached peak primary industries. Our substantial land and water resources are already overburdened. NZ economists have harmed the NZ economy in allowing this major miscalculation and misallocation of resources to primary industries.

Tourism and international students is a $15 billion and growing services industry and with the Americas Cup in 3 years, expect more foreign workers as the syndicates bring in their sailors, trainers, chefs, design and build team, supporters and fans. Expect more and more people rather than less. The best service is always more people rather than less.

Until we start to grasp that our billion dollar subsidies need to go to industries that actually make leading edge mass market products that the world requires rather than the abysmal milk and meat production that 10 million cows can offer. A highly subsidised Samsum company delivers $350 billion in sales with 350k people. Our 10 million cows deliver $15 billion in milk and meat. You are never going to get high productivity from primary industries, tourism, international students and services. It is never ever going to happen.

LikeLike

Correction: dropping immigration target to 15k from 50k.

LikeLike

Where would you begin? What Industrial activities do you reckon we could get scale out of?

LikeLike

In this following list Education and Tourism don’t even get a mention, but, what is noticeable is in the list of imports, the bulk are mainly focused on transportation. We need to stop importing planes and helicopters (sarc)

NZ is the 54th largest export economy in the world and the 56th most complex economy according to the Economic Complexity Index (ECI). In 2015, NZ exported $35.8B and imported $35.7B, resulting in a positive trade balance of $71.8M. In 2015 the GDP of NZ was $173B and its GDP per capita was $37.6k.

The top exports of NZ are Concentrated Milk ($4.75B), Sheep and Goat Meat ($2.24B), Frozen Bovine Meat ($2.11B), Butter ($1.62B) and Rough Wood ($1.62B). Its top imports are Cars ($2.94B), Crude Petroleum ($2.07B), Refined Petroleum ($1.23B), Planes, Helicopters, and/or Spacecraft ($1.18B) and Delivery Trucks ($1.06B).

LikeLike

Rocket Lab should have been funded by the hundreds of millions. The venture capital here is too small. On Q&A today, Robert Beck of Rocket Lab made it very clear he had no choice but to become a US company in the last few year dues to lack of funding. The NZ government should have locked down the technology in the interest of National Security.

LikeLike

Whitecloud, not too sure the point you are making as Tourism and international students is a $15 billion export industry which is much larger than the numbers that you are putting forward as our other top industries which I think is in USD rather than NZD. The imports like aircraft is to support the tourism industry with Auckland Airport handling 19 million passengers each year.

LikeLike

This is damned good Michael.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Read both. Time for your own YouTube chanel Michael.

LikeLike

Please rewrite that excellant introduction adjusting the figures and replacing NZ 1913 with PNG 2018.

LikeLike

Good one Michael. You may well have read it already, but if you haven’t, you’ll find Steven Pinker’s latest book ‘Enlightenment Now’ does a very good job of documenting the global rise in living standards and its rub-off positive effects on any number of social problems

LikeLike

Thanks Donal. I haven’t read Pinker’s book, but from short articles he has done on it, various reviews, and from interviews with him it sounds like rather a mixed bag from my perspective – good on the improvements in material living standards while clearly seeing religion as something antithetical to his overall version of “progress”. In my address this week I deliberately kept emphasising that I was talking only about material living standards – directly connecting to “productivity”.

I touched on some of PInker’s arguments, and some corallaries, in a post a couple of months ago on the choice ‘would you prefer to live in 2017 or 1967″ on my other blog.

https://amongtraditions.wordpress.com/2018/02/14/2017-or-1967/

On balance, I was inclined to favour 1967.

LikeLike

My Great grandmother died in the 1920’s. She had a hard (including death of an infant) but wonderful life and what stood out was “kind friends and family” plus living in an environment to die for (early settlers choice).

Also

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/letter-to-peter-collinson/

LikeLike

What stands out today is a concentration of opinion (media tyranny).

LikeLike

Lots of comments on RNZ Facebook good and bad. Robert Gore had the best (long).

These are among the worst

Richard Vell Unfortunately his numbers are cooked up, this is why we cant have fair debate on immigration. 45000 residence visa is just made up number. Number of residence visas granted per month is only 800. Anyone can go on immigration nz website can check this fact. He claims migrants are “little less skilled than average NZ workers” without providing any evidence to substantiate his claims. Its just saxon propaganda.

…….

Jack Jones Nope, the economic problem is wages have not kept up with productivity growth so working people do not have the money in our pockets to spend which would keep the economy ticking over. #101

……

Richard Vell Well this had to happen, how did Britannia get all its wealth? by looting and steeling from the same 2nd and third world countries don’t you think. Unfortunately, we cant do that anymore, so our standard of living is declining.

LikeLike

You’ve acknowledged the high productivity economies are in “catch-up mode”. And they aren’t just in catch-up mode from our position with a GDP 2/3 of the US. They’re on a run from a starting position a tiny fraction of the US, an order of magnitude or two behind. So a cynic might think they’re just running on momentum now. They have the kind of culture conducive to that growth rate because they’ve been doing it for a while.

Reflecting on this and on your posts in general, it seems hopeless. If you are correct in your arguments against immigration then we could stall our decline by cutting immigration to just 10,000 or so skilled people a year. But I don’t see any promise of being able to turn things around to an average of 2% like you say.

When I look at the fundamentals myself I can’t think of a great reason for optimism. If we’re really lucky, well get a half decent trade deal with the UK in the next few years. Long term, the agricultural sector will be challenged by clean (lab grown) meat products; tourism will grow but you can’t build a high productivity economy on tourism; the world’s economy will continue to transform with much of the meaningful growth powered by AI tech/big data. One irony of the Internet age has been how much distance *does* matter, with key industries in Silicon Valley, Shenzhen, and other hotspots. So absent a few stars- Xero, Orion, Vista – it’s not clear NZ can build prosperity on the information economy.

Michael, do you see any meaningful path forward? What are policies that might get us on track, in your view?

LikeLike

There are some comments relevant to this in my response to a couple of people on Saturday’s post https://croakingcassandra.com/2018/05/19/a-wager-for-the-minister-of-finance-to-consider/comment-page-1/#comment-24947

I don’t know if we can match Belgium, France etc, although as I noted to an audience the other day, despite their locational advantages, they also hobble themselves with high taxes etc. I’d have little doubt we could at least halve the gap (roughly, catch up with Australia), and we’ll never know if we can go beyond that if we don’t try.

And trying seems likely to involve recognising the big disadvantages of location, working with the people we have (not trying to drive up the population – esp when the advanced world as a whole has relatively flat population). We have the skilled people, reasonable quality institutions, ideas and entrepreneurs, but it is (a) insane to be taking so many more people, and (b) doing so has skewed relative prices against those trying to take on the world from here. Stop that and I’d be astonished if we couldn’t do a great deal better (bearing in mind that insisting on a big carbon reduction target in a place where ag emissions are big and hard to abate is yet another self-imposed skew against the economic possibilities that could otherwise be realised.

Even if the conclusion is one of despair, even that should lead us to stop loading up the country with ever more people. It makes some sense to welcome in lots of people if the economy is doing (structurally) very well, but not when it has underperformed for decades.

LikeLiked by 1 person

With GDP still running at 3.5% not many people are actually concerned about productivity. As long as there is food on the table, beer in the fridge, a 55 inch TV for sports and a roof over our heads and a job that pays enough for that most of us are very contented.

LikeLike

Perhaps, but (a) more than half of any growth rate is just an increase in population numbers, and (b) some of the rest is just NZers working more. Prosperity usually involves working less – as today’s NZers work a smaller share of their lives than their ancestors 100 years ago did.

Perhaps also to the point, you may have noticed the bipartisan angst over child poverty in the election campaign, or regular moans about low wage increases. Productivity is part of dealing with those sorts of issues.

Life is almost always comfortable for employed professional late middle-aged people (families like mine, and I deduce like yours). That is so in Argentina, Russia, China or other places much poorer and less productive than NZ is. Life is much less comfortable for many other people.

LikeLike

We still seem stuck at the same problem, not really understanding the problem and failure to approach the problem with anything other than superficial analysis. This results in attempts to apply solutions that work else were here clearly not here, remember the let’s imitate the Asian tigers, then the Celtic tiger, etc, etc. No one actually seems to have any real original ideas, most seem to be on the level of whether or not unionisation of the stewards on the RMS Titanic would have improved the profit margin. We need to realise we are the nation equivalent of Venice, an entire continent of which only 8% sits above sea level. We need to starting thinking originally, particularly now humanity is on the verge of a proper disconnect between population and maximum possible productivity. We could have a continent sized economy with a 5 million population.

Clearly we need to look at what already works here. Business that have a large domestic market here tend to also be competitive exporters, think Gallaghers and the like. In the past a major strength noted by oversea observers was that we could get all the nations experts in a room and sit down to get a way forward for a particular problem, this seems to have disappeared under a mass of consultants and other irrelevant hanger-on’s. It appears that the distance to market issue as a limit on this economy is largely over rated except for small companies or companies with a limited home market. More critical is the failure to realise that the population size and critical mass limits means we need to rationally (not ideologically) pick specific sectors to develop.

Any great creator of wealth that is easy & simply isn’t worth it as we end up completing directly with everyone else looking to cheap and simple wealth (software is a classic of what everyone think is an example of this). Hard is much better, offering much greater reward with limited competition, the classic example is the US aerospace industry they have a large domestic demand and have made very large investments in research for last 90 plus years (much though NASA and the DARPA) which means they are still very much the world leaders. It also needs to be noted that the military’s demands are a great part of this success (jet engines, digital imaging, silicon chips are all direct outcomes from military support research / labs). There is no point engaging in research if there is no domestic demand and domestic production isn’t competitive if there isn’t any research, and companies just don’t tend to engaged in research,unless government driven.

Going back to the continent slightly sticking out of the water. There is much new technology that will fundamentally change our interaction with the sea. We could be the natural leader in this field, we have more water than just about anyone else. This could easily be developed, focusing on developing technical capacity for subsea mining and its equipment (not the 3rd world approach of just giving away most of the margin to avoid all the risk approach of National), following by the many profitable subsea activities that no one knows exists just yet. There is no real reason we couldn’t be the richest nation on earth in 20 years.

LikeLike

With the UN having recognised that we are actually a continent, Zealandia, our maritime borders now stretch much much further to the edge of the continent. This means that the extent of our reach in terms of Oil and mineral exploration and ownership goes much further than it previously did. Oh no the Labour government just went and stopped future oil exploration.

LikeLike