Partly in the cause of research, and partly because I have a bit more time these days, last night I went to my first ever Wellington City Council public consultative meeting. The Council is keen to promote more medium-density housing in Island Bay (and several other suburbs). To their credit, they have gone beyond the formal requirements of the RMA and are undertaking an informal community consultation, with information delivered to every household, very early in a process that they hope will eventually lead to a change in the district plan. I think I recall seeing a comment in the recent Productivity Commission report commending this WCC initiative.

The meeting wasn’t an edifying experience, but then I’m not sure that was a surprise.

It doesn’t help that the Council doesn’t have a great reputation in Island Bay at present, despite (or perhaps even because of ) the Mayor being a local resident. There has been a sense of them ignoring community opinion – the seawall, severely damaged in a storm almost 2.5 years ago, still not repaired, and a hugely acrimonious debate over a rather expensive new cycle-way which can’t pass any conceivable cost-benefit test. All that makes for a degree of cynicism – vocally expressed last night – about the genuineness of any consultative process. (And all that is before one considers the folly and hubris of an organisation that wants to put tens of millions of dollars into an uneconomic airport runway extension. )

There is also a degree of hostility to the local Special Housing Area. I don’t fully understand that hostility. The moribund buildings of a former Catholic school (closed by the church 35 years ago) are less than a couple of hundred metres from our place, and I have long looked forward to them being replaced with houses or apartments[1]. Island Bay is a popular place to live, and this private land is not currently being used at all. If someone is keen, at last, to develop it, it might be small step towards keeping housing only moderately unaffordable.

But that is all by way of background to the medium-density housing consultation, which continues to puzzle me. Question 1 on the WCC consultation form says “Where should medium-density housing development happen in your suburb?”, which on the one hand presumes that people agree that such development should happen at all, and on the other leaves me scratching my head thinking “well, surely on any site where someone finds it worthwhile to do so”. And then “what standards of design should the medium-density housing meet?”, and I’m thinking “whatever works best for developers and willing buyers”. But I’m pretty sure I was the only person in the room last night thinking anything remotely along those lines. Not that I would be any more sympathetic if it was, but Island Bay is not some olde worlde place with uniform Edwardian architecture. It is a pleasant mix of the old and new, where the number of dwellings per square kilometre has increased enormously in the 37 years since I first came here (through some mix of infill, new streets further up hills, and medium-density developments on several larger existing sites).

Instead, it was a case of the regulatory state run rampant (from both the supply and demand side). The Council staff had a Powerpoint presentation which started well – headed “Housing Supply and Choice”- but it was pretty much downhill from there. Instead of a focus on facilitating landowner rights, consumer choice, and competition, the whole thing flow from a central planner’s identification that Island Bay is one of those places with a strong “town centre” and hence a candidate to promote medium-density dwelling. I was trying to work out why Island Bay is identified and not, say Seatoun – similar public transport, similar vintage houses – and I can only conclude that it is because the latter lacks a supermarket, an anchor of the “town centre”. It puzzles me what happens to the Council’s logic if the(small by modern standards) supermarket were to close – or if the Council were, for once, to do a hard-headed cost-benefit analysis and close the small local library. The local identities who have run a stationery and children’s bookshop for the last 40 years are just about to retire, and the chances of that business continuing can’t be strong.

But part of the consultation is about preparing a “plan to guide development in Island Bay town centre”. The so-called “town centre” is perhaps 15 private shops, in a higgledy-piggledy variety of styles, several of which are threatened by the Council/government earthquake-strengthening requirements. But why do we need bureaucrats “planning” a “town centre” to “ensure coherency across different developments and help contribute to a more attractive and vibrant centre”? At the meeting, the bureaucrats talked of checking to ensure that “we have located the town centre in the right place” – to which one response might be that the market already resolved that one more than 100 years ago. Sometimes I think I must be missing something important, but then I think it is just bureaucrats and local politicians run amok.

And the Council draws on some demographic projections for the next thirty years to argue that they need to facilitate housing for older people who will want to downsize but stay in the neighbourhood. Quite possibly there will be such a demand – I expect to be one of the older people, although I don’t intend going anywhere – but when you rely on such projections, and especially when you can’t even adequately explain how they are done, you are on a hiding to nothing. Council staff drew a lot of fire for those numbers. Much of it was quite ill-informed, but it was hard to have much sympathy. Inevitably, holes appear the moment you prod, ever so gently, a projection of that sort. Choice and flexibility etc should be the watchword not “we wise bureaucrats have identified this specific need 25 years hence and want to change the law now to meet it”.

And then Council staff talk of undertaking a “character assessment of the suburb”, and burble on about wanting to “make sure that all new development is high quality, the design and appearance fits in with the surrounding environment, and it can stand the test of time”. Just like the IMF the other day, the Council is keen on only “high quality” housing, but why is that something for them to decide, rather than willing buyers and sellers?

And so it goes on. Bureaucrats talk of a desire to “decrease private motor vehicle use” and “encourage more walking” (and hence medium-density housing might be encouraged five minutes walk from the town centre but not seven). What happened to facilitating choice I wondered? Oh, and fixated on accommodating possible demands from old people, the chief planner present commented that the Council wanted to encourage medium density housing in which the core living facilities were on the ground floor. It gets tedious to say it, but isn’t there a market test in these matters? Dwellings that meet market demand will sell better than those that don’t. And aren’t maximum site coverage rules one of those things that work against single storey dwellings?

So the Council staff were bad, but they met their match in the residents. There was a strongly negative reaction to the notion that anyone outside Island Bay should have any say on the proposed changes – forcing staff to downplay the very suggestion. There was a great deal of concern about protecting people’s house prices (up), but no apparent sense that allowing land to be used more intensively would, all else equal, make it more valuable not less. There was concern about what sort of socially-undesirable people might move into these new dwellings (and this is one of the more left wing suburbs around), and so many demands for controls and restrictions that – briefly – the Council staff were forced to defend the ideas of choice and private property rights. One person was appalled at the idea of three storey dwellings – this is a suburb surrounded by, and partly built on, high hills. And not a mention from the floor – although it was hard to get a word in – of the idea that people should be able to use their own land as they liked, or of the attractions of helping keep places only moderately-unaffordable so that perhaps one day our children might be able to buy here.

Council officers were reduced to plaintive observations that “the city is growing and people have to live somewhere” (downtown high rises appeared to be the response from the floor), which I might have sympathised with were it not for the historical evidence that as cities get richer they tend to get less dense not more dense – something the planners are no doubt oblivious to, and perhaps disapproving of. Harder to encourage walking I suppose, as if technological change had not given us options. The invention of the tram helped open up places like Island Bay in the first place – otherwise it was a bit far to walk to work.

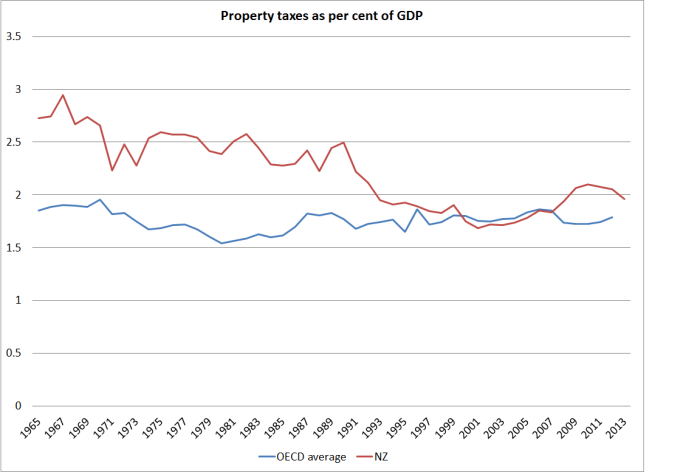

I recently criticised the Productivity Commission for the bits of its land supply report that appeared to endorse the way some (most?) Councils were setting out to promote compact urban forms (rather than to facilitate choice and respond to individual preferences). I came away from last night confirmed in that view. I’m all for allowing more intensive development, not just in individual suburbs but across Wellington (and all other areas for that matter). But the pressures to do so, and the sorts of vocal clashes I witnessed last night, arise largely because Councils are reluctant to see the physical size of the city grow. Wellington might not have much flat land – although most people probably don’t live on flat land in Wellington anyway – but any time I fly in or out of the place I’m reminded that it is not short of land. Regulatory restrictions – and perhaps at the margin the rating system – combine to make it optimal for developers to release land only slowly, and that helps keep the price of all urban land high. For landowners in existing suburbs part of the appeal of more intensive housing (eg infill on existing rules) is realising the value that regulatory restrictions had artificially added to land prices. If a section on our main (flat) street, The Parade, is worth $500000 or more, subdivision and more intensive development must be attractive. If it were worth $150000 – which it might well be if new building opportunities were readily available on the periphery (or in greater Wellington’s case, most actually between Wellington on the one hand and Porirua and Lower Hutt on the other)), more people would probably prefer to keep a decent-sized backyard or front lawn. I’d probably still favour allowing more intensive development, but I don’t think we’d see much of it, especially this far from the centre of town. Space appears to be a normal good.

As it is, the confrontations will go on. I don’t like to predict how our one will end, but whatever the outcome the process is a pretty unedifying, and unnecessary, one.

[1] There is a beautiful chapel in the buildings, and I would be sorry to see it go. But I’d also be reluctant to see my rates used to save it, especially if doing so compromised the development opportunities of the site.