Hamish Rutherford had an article in the Dominion-Post yesterday in which he quotes the Prime Minister as claiming, on the one hand, that the recent high net migration inflows are a “time of great celebration” and, on the other hand, that most of the arrivals are something the country “can do nothing about”. Rutherford had a follow-up piece yesterday with some comments from me and from a couple of other economists – a nicely balanced group; one relatively negative, one relatively positive, and one “it depends”.

Actually, I suspect nobody much shares the Prime Minister’s glib “time to celebrate” sentiment. You can be as much a believer in more liberal immigration, or even open borders, as you like, but it still repays stopping to look at just why things are as they are. Ours isn’t that positive a story.

Of course, contrary to the headlines, the net inflows we’ve been seeing recently are not “record migration” in any meaningful sense. Yes, the net PLT inflow is at a record level, and perhaps even as a share of the population at any time in the last 100 years or more. But the limitations of the PLT numbers are well-known. If one looks instead at the total arrivals less total departures, the inflow over the last year has been around 60000. By contrast, in 2003 the annual inflow peaked at 80000. New Zealand’s population is now around 15 per cent larger than it was in 2003, so the per capita inflow over the last year or so has only been about two-thirds the size of what we experienced in 2003. So the current inflow is large, but not really at record levels.

And although the target number of residence approvals for non New Zealand (and non-Australia) has been 45000 to 50000 per annum for years (despite the growing population), only 43000 approvals were granted in 2014/15, compared with almost 53000 in 2001/02. I think MBIE even objects to the use of the word “target”, but however one characterises the number that Cabinet set, it isn’t met precisely each year. In fact, perhaps reflecting the relatively weak domestic labour market since the recession, 2009/10 was the last year in which residence approvals were above 45000.

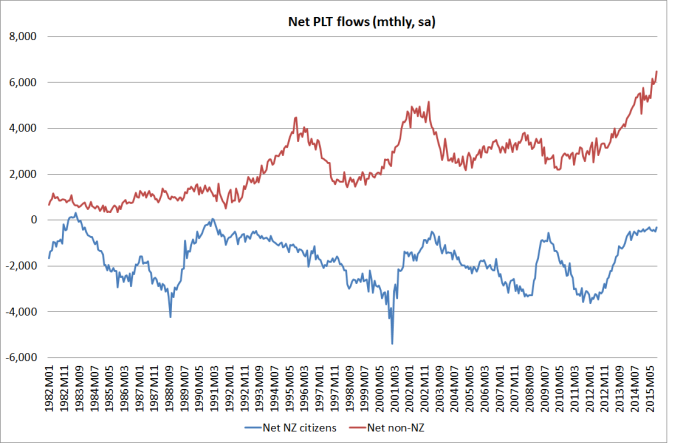

And can we control the total net flow numbers? Well, not really since New Zealanders are free to come and go, and of course any foreigners who has come here (needing advance approval) can also leave any time they like. Since the trough in 2011/12, the increase in the net PLT flow has been roughly evenly split between New Zealand citizens and other citizens, but over the last 18 months the decline in the net NZ outflow has levelled off, and all the further increase has been down to increased net inflows of non New Zealand citizens. At around 6500 in the last month, that net inflow probably is a record, even in per capita terms (SNZ don’t report the total migration data by citizenship). Every non-New Zealand citizen coming to New Zealand needs the approval of New Zealand authorities.

It is worth bearing in mind that there is still a net outflow of New Zealanders each month. The last times there were even modest inflows were 1983 and 1991, both occasions when Australia’s economy was in recession. Given that the stock of New Zealanders living abroad is now much larger than it was in either 1983 or 1991, it would have been easier to envisage a larger net inflow of New Zealanders this time if our economy and labour market were really performing well. But they aren’t. We can’t rule out a small net inflow of New Zealanders at some point, but it hasn’t happened yet.

We can see the role that Australian conditions are playing by looking at the flows of New Zealand citizens to and from Australia, and the flows of New Zealand citizens to and from other countries. If the story were one of a strongly-performing New Zealand, I’d have thought we might expect to see New Zealanders flocking home from all corners of the globe (and not leaving for the rest of the world). New Zealand citizen arrivals for the rest of world (other than Australia) are at quite a low ebb – well below, for example, what we saw in 2003 when our unemployment rate was dropping sharply.

And New Zealand citizen departures to the rest of the world, while quite notably lower than they were in earlier decades (tighter restrictions in place like the UK?) have been pretty stable for the last six years.

Instead, all the action in the New Zealand citizen flows is in those between New Zealand and Australia, suggesting that it is conditions in Australia that are at the heart of the story.

The unemployment rate in Australia is around 6 per cent, and there is now a much greater awareness than previously that the rules in Australia have changed for New Zealanders. Any one going now, and who has gone in the last 15 years, is largely on their own if, for example, they can’t find a job, or they lose their job. And their kids are often in some limbo, not really New Zealanders and unable to become proper Australians either. Without that sort of welfare backstop if things go wrong, it is much more attractive than it was for anyone remotely risk averse to stay at home until the Australian labour market is much more robust. It may be less attractive to try even then than it once was. And that is so even though average incomes and real living standards in Australia are higher than those here, and that gap has shown no sign of narrowing. But it is not that to any material extent there is a net outflow of New Zealanders from Australia (although the uptick in New Zealanders coming home isn’t something we’ve seen before), it is simply that for the time being the outflow to Australia has dried up.

Given that the adverse income gap has not narrowed and that our unemployment rate is high, nothing in that is a cause for celebration in New Zealand. If anything, rather than reverse. The more highly productive Australian economy has been an attractive option for New Zealanders for decades – enabling New Zealanders to improve their lot (and taking downward pressure off factor returns in New Zealand). If that alternative outlet is less easy or safe to take advantage of, New Zealanders as a whole are a little worse off. If, for example, people relocating from Invercargill to Auckland were made ineligible for welfare benefits, Invercargill as a whole would be worse off economically – even though some of the parents in Invercargill might be pleased to have their kids and grandkids a bit closer to home.

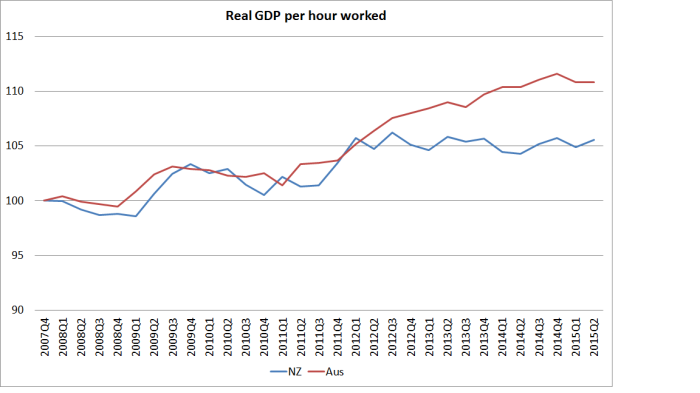

And what of New Zealand’s economic performance relative to Australia? Real GDP per hour worked is a pretty good timely measure of relative productivity performance . As the statistics stand at present – who knows what revisions will eventually show – the New Zealand performance in the last few years has been really bad by comparison with Australia’s. Data suggesting no productivity growth for four years, while Australia has gone on achieving productivity growth, just reinforces a sense that the reduced outflow of New Zealanders to Australia – partly temporary and probably partly permanent – is something bad for New Zealanders, not something to celebrate.

It needn’t always be so. I wish we had the sort of strong sustained economic performance, built on rapid productivity growth, that was putting us a path to income convergence (once again) with Australia. If so, I reckon we’d see the net outflow turn into a material sustained inflow. That would be cause for celebration. This is not.

And all that with barely any discussion of the non-New Zealander flows. But just briefly. The Prime Minister correctly notes that foreign students are an export industry. But I’d be more reassured by that if it were not explicit government policy to encourage foreign students, not on the intrinsic strength and quality of our own (middling at best) universities, but as a pathway to residence here. Since there is no evidence that such permanent immigration to New Zealand has represented a net economic benefit to New Zealanders – neither MBIE nor Treasury nor relevant ministers have been able to cite anything remotely convincing – it seems that we are really just back in the export incentives business. Instead of writing cheques, we write (the possibility of) a visa. Export incentives “worked” in the pre-liberalisation period to – people do what they are incentivised to do so we got more subsidised exports – but it still wasn’t good policy. It wasn’t under Muldoon and Rowling, and being done by Steven Joyce and John Key doesn’t change the proposition. I’m not, at all, suggesting we should discourage export education, but let it stand on its own merits if the current numerical success is really to be a cause for celebration.

The Prime Minister also reckoned that “many of the arrivals fell into either highly skilled or investor categories”. In the last year, just 1353 residence visas were issued under the investor and entrepreneur categories (about a third as many as were being granted in the early 2000s) and as I noted in an earlier post MBIE’s research has highlighted just how questionable the net economic benefit of these migrants has been.

One of the MBIE papers is on the web. It discusses some work on investor migrants – who already, in effect, buy their way into New Zealand. The aim of the programme is to import people with business expertise and entrepreneurial skills, presumably to boost productivity in New Zealand. And yet in these surveys of people at various stages of the investor migrant process (and in which respondents must have been at least partly motivated to give the answers MBIE wanted to hear, even if results were anonymised), 50 per cent of the money investor migrants were bringing in was just going into bonds, and only 20 per cent was going into active investments. We aren’t short of money, but may be of actual entrepreneurial business activity. And 70 per cent were investing only the bare minimum required or just “a bit more”. And these people aren’t attracted by the great business opportunities in New Zealand, but rather by our climate/landscape and lifestyle. It doesn’t have the sense of being a basis for transformative growth.

Set alongside the 1353 investor and entrepreneur visas were 4477 parent visas last year.

As for the highly skilled, I have covered previously and, in a succession of posts, at somewhat tedious length the question of just how highly skilled our skills-based immigration programme is. Here, from the tables in MBIE’s excellent resource, Migration Trends and Outlook, are the numbers for 2014/15 –the top few occupations for the principal applicants for residence applications under the skilled migrant stream.

| Chef | 699 |

| Registered Nurse (Aged Care) | 607 |

| Retail Manager (General) | 462 |

| Cafe or Restaurant Manager | 389 |

It doesn’t have a strong sense of something to celebrate – the highly skilled of the world flocking to New Zealand and in the process strengthening our own skills levels and productivity.

And finally, the Prime Minister is quoted as saying

“Show me a country which is booming around the world where more people leave it than come to it”

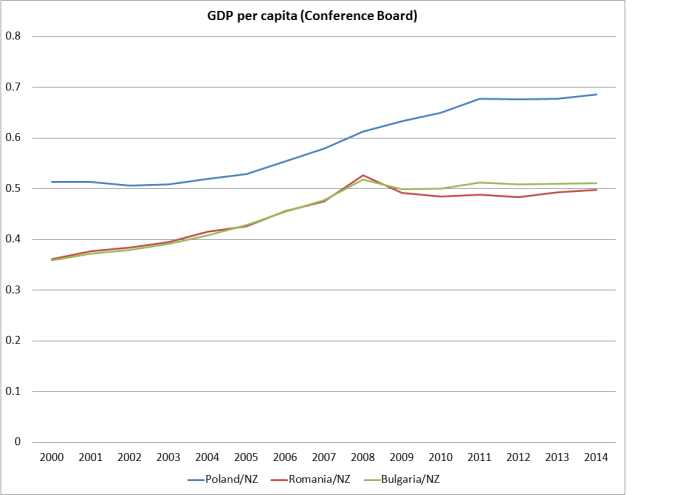

Glad to Prime Minister. Consider Poland, which has been one of the strongest performing OECD countries in the last decade, and which has had steady net migration outflows. Poland is gradually catching up to the living standards in Western Europe, but it has a long way to go. In the meantime, the opportunities for many Poles are still better abroad. Perhaps it is easy to dismiss Poland as just an ex-communist country, but it has done what New Zealand has failed to do – make substantial progress towards converging with living standards elsewhere in the advanced world. In 1989, Polish incomes were estimated to be less than a third of those in the United States. Now they are almost half.

Bulgaria and Romania are less striking stories, but they are also countries with substantial net migration outflows – again, the opportunities abroad are better than those at home. But both countries have managed to grow materially faster than New Zealand since 2000, and have matched New Zealand’s per capita income growth in the years since John Key has been in office.

Immigration policy is not, by any means, the whole story. It probably isn’t even the bulk of the story in these countries. But net inflows of people aren’t always good and net outflows aren’t always bad. It depends. There is no real reason to believe that the current net inflows to New Zealand – or even the reduction in net outflows to Australia – are cause to celebrate. I suspect that, if anything, the inflow is compounding the underlying productivity problem. But there is certainly no sign that it is either a response to us having solved those problems ourselves (and thus being on some convergence path back to the rest of the advanced world) nor that the inflow will be any more likely to bring about a transformative lift in productivity than the previous inflows over the last 25 (or 75) years have.

Another analysis out today on the effect on Auckland housing;

http://www.interest.co.nz/property/78828/expected-increase-new-home-construction-wont-be-enough-dent-aucklands-housing

Here’s JK with his “cause for celebration” comments in respect of the explosion of Indian student visas;

https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/indian-students-not-here-to-study-says-peters

And on that same subject a few days earlier, where Immigration NZ raise the red flag on this ‘education export boom’ (as Key refers to it);

http://m.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=11548482

So, one has to ask in the face of rising disquiet and evidence to the contrary – even from his own immigration officials – what on earth is his underlying objective in trying to spin this boom as a benefit?

There has to be a reason… and it can have nothing to do with economics. It’s almost as if there is an intent to create social discohesion, particularly in Auckland. But why?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suspect quite a lot is just about managing the 24 hour news cycle. One quick, rather glib, set of comments and the PM got a substantial positive story. And then it was on to the next issue and next news cycle.

After the journalist did do a follow up story, getting reactions from economists, but not until the day after his first story. I’m not necessarily blaming him – he has bosses and time constraints etc – but politicians, like others, respond to incentives, and they know how the system works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not too sure what all the fuss is? John key is perfectly correct. Things are certainly looking good iso far, in NZ, especially in the context of a uncertain world. Jobs are readily available for those that do want to work. Housing looks expensive in Auckland but when you consider that the Unitary plan would virtually double the income potential of most residential property in Auckland as a MINIMUM, those prices look rather reasonable and in a lot of cases even cheap from a commercial context.

LikeLike

When NZ education institutions have spent $1 billion in the last couple of years plus another $1 billion to be spent in the next couple of years on student infrastructure, you can virtually guarantee that the 7 big educations institutions would be marketing around the world to increase international fee paying students. Can’t really blame John Key for that. It is private enterprises doing what they do best and that is to make a profit and and big $2.85 billion contribution to export earnings.

LikeLike

Compare that with Australia’s International student’s contribution to export earnings of A$18 billion, our student numbers are paltry. We should aim for Australia’s $18 billion export earnings from the international student market and ask ourselves why we are not able to attract more international students???

http://monitor.icef.com/2015/08/australian-education-exports-reach-aus18-billion-in-201415/

LikeLike

And I’m not (blaming Key for the institutions), but in fact a huge part of the attraction is the bit the govt is directly responsible for – the prospect of a residence visa, combined with work opportunities while enrolled in study. That is the “export incentive” dimension.

(And, of course, lots of those on student visas are not enrolled at universities. Again, nothing wrong with that in principle, provided the quality of the education is the product.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Frankly, we are way at the bottom of the world, we need every incentive to get people even remotely interested in studying here in NZ. How do you expect to catch up to Australia when we only export a paltry NZ$2.85 billion in International Fee paying students when Australia is exporting A$18 billion in International Fee paying students a year? We must ask ourselves weather our government is doing enough to attract more students. It is not less that we should be concerned with.

LikeLike

Given that Australia has five times the population of NZ, and more good universities (we have nothing with the reputation of Sydney or ANU) our export education numbers look pretty respectable.

The big incentive, as I implied, would be a lower real exchange rate. The biggest obstacle to a persistently lower exchange rate is persistently high interest rates. And the story behind those is the investment needs of a rapidly growing population in a country with a rather modest savings rate. Cutting the immigration target would, largely, deal to that issue. As I said yesterday, it is all in the paper I wrote in 2011. I’d be really interested if you have some alternative perspectives or challenges to that way of thinking about the issue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Australia has 5 times the population but export earnings of 10 times in international national students. Therefore it is more students we want and not less.

LikeLike

Looks like perhaps 7 times the export earnings. And it has better universities to start with – can’t charge premium prices for mediocre quality. But as Blair has pointed out, even in Aus a lot of it is a rort; all about skewed incentives rather than quality education. I have a great deal of time for Judith Sloan on issues like this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is no obstacle to getting a lower exchange rate and that is to drop the interest rates.

LikeLike

Umm….the universities we have are not as good, on average, as tho of Australia, and of course they have many more universities. Being a safe English speaking country is an advantage, but it isn’t a huge one and it isn’t obvious why students would choose to come here if they could get anywhere else. And, of course, our prices aren’t cheap – with an exchange rate averaging say 55 cents export education might be a more feasible proposition, on its own merits (the price vs quality mix).

LikeLiked by 1 person

My wife and several friends are Australian academics. I am very sceptical about Australia’s education export miracle. There are two main issues: 1) the dumbing down of standards to cater to foreign students with poor basic skills (don’t get me started on some of the interns I have had recently) and 2) the corruption of senior administration staff caused by the amount of money sloshing around the system.

In line with my own experiences is this comment from Leith van Onselen of Macrobusiness recently (excerpted as behind paywall): “Over the past few years, several people in the higher education sector have expressed concern to me that education standards are being eroded as education providers have turned into ‘factories’ selling degrees/diplomas, often to foreigners as a pathway to future permanent residency.

Those that I have met involved in teaching/lecturing have complained that they often feel unable to fail students for fear that it will lead to a backlash, resulting in less ‘sales’ of degrees/diplomas in the future. In turn, they believe that education standards and the value of higher education are getting watered down, with obvious repercussions for future productivity.

Over the past year, a series of reports have emerged highlighting these concerns in greater detail. For example, Fairfax has previously reported that international student colleges have taken cash kickbacks in return for helping overseas workers and students win Australian visas using fake qualifications. The ABC has made similar reports.

Four Corners has also previously uncovered international education university cheating and plagiarism rorts.

Today, The Australian has released three articles (here, here and here) uncovering widespread rorting by private colleges.

According to one report, Australian private colleges were handed more than $1.4 billion in government-funded VET Fee -Help loans last year, which was four times as much as was provided to public vocational education and training providers. Yet, only 14,400 students managed to complete courses at private colleges last year, compared with 18,400 students at TAFE and other public providers. Thus, the figures reveal that private colleges are inflating course costs but providing very poor educational outcomes.

Indeed, according to another Australian report, Private training colleges have tripled tuition fees in three years and lumped taxpayers with billions in tuition loans:

Official data reveals the average tuition fee for an information technology diploma soared from $2779 in 2011 to $18,735 last year. Colleges are charging students an average of $15,493 for a diploma of business management that cost $4623 in 2011.

Business courses, including diplomas in hair salon management and training for “fitness business professionals’’, account for half the $1.7bn students borrowed for vocational training courses last year.

Across all fields, the average tuition fee for a vocational training diploma has tripled from $4814 to $12,308 in three years, the latest federal Education Department data shows.

The Australian’s Judith Sloan summarises the problem as follows:

Fly-by-night operations could lure students to expensive, inadequate courses and send the bill to the federal government. Students were urged to take loans on the understanding they would not have to repay the principal…

The above reports highlight an inherent conflict with Australia’s higher education system: how to maintain education standards at the same time as maximising profits, be it via education exports or domestic tuition?

Producing ‘degree/diploma factories’ obviously will maximise profits, at least in the short-term, but will lead to the dilution of standards and the value of higher education, negatively impacting on productivity. However, by enforcing standards, the sector risks lowering sales of degrees/diplomas, thus negatively impacting profits.

A related issue is that Australia’s education system has become an integral part of the immigration industry – effectively a way for foreigners to gain backdoor permanent residency to Australia.

LikeLike

Thanks Blair. The final para of Judith’s comment highlights that these are serious problems in both countries. Everyone responds to incentives, and when govts are so skewing the playing field the outcome is unlikely to be efficient/desirable.

LikeLike

Seems like a problem of policy coordination between immigration targets and infrastructure investment/funding requirements. And I don’t want to be a ‘fun sponge’ but perhaps the chef, retail and café manger skew goes to the heart of the issue: a little too much consumption (house prices always go up right?) results in too little saving which means higher nominal rates to keep the inflation dragon at bay. On that note, house looks good in the sun so about time for an afternoon flat white…

LikeLike

NZ Households have $143 billion in cash savings in banks plus $49 billion in listed shares, a total of $192 billion in very liquid assets for only 4.2 million people. is that considered too little savings? With household debt of only $152 billion would you not consider that too much savings rather than too little?

LikeLike

Correction: Household debt of $158 billion

LikeLike

….if household savings aren’t too little, why is NZ a debtor nation? Do you think the households with the liquid assets are the same as the ones in debt? If the $49bn listed shares were liquidated on mass, would the monies received sum $49bn? To my mind, aggregate data masks imbalances within and between sectors??

LikeLike

The critical point is that what matters to our external indebtedness is national savings (ie corporate plus household plus government). Our national savings rate has long been quite low by advanced country standards. On the other hand, our investment/GDP has been around the OECD average (it probably “should” have been higher, given our well above average population growth). the current account deficit is just the difference between savings and investment (a difference identically equal to that between exports and imports), and the NIIP position is just the accumulation of the current account deficits (adjusted for any valuation effects).

LikeLike

Michael, it seems the weakest link in your chain is the assumption that higher immigration results in higher interest rates. How settled do you think the evidence is here?

LikeLike

In the short run it is largely uncontested (and has been for decades). An increase in immigration, all else equal, raises interest rates. Recent RB research again confirmed that result.

But other than the sense in which the long run is just a succession of short runs, the longer term picture – my real interest – is more contested. The stylised facts are pretty clear. We’ve had persistently higher interest rates than any other advanced country on average throughout the last 25 years. There is no sign of the gap narrowing, and no sign that the difference is just a difference in inflation rates – it is clearly a difference in real interest rates. There are two competing hypothesis. One is that the higher interest rates are a risk premium on account of the large negative NIIP position. I counter that if that were so we should have seen (a) a surprisingly weak exchange rate, not a surprisingly strong one (risk premia lower asset prices), and that the risk premia etc should have led to a rebalancing in the economy that saw the imbalances go away. Many people – but not all by any means – accept that reasoning, regardless of their view on immigration policy. But there are no definitive empirical studies. If my logic is right, then the difference in interest rates must reflect the difference between desired savings rates and desired investment rates. Plenty of people will accept that as quite standard macro. The differences are then more ones of policy preferences. People who I respect well in the bureaucracy will accept that immigration policy puts pressure on this S/I imbalance, exacerbating it, but will often prefer to focus on the savings side. For those who favour compulsory savings for whatever reason this is an obvious leap. But it is also the relevance of the point I mentioned last week – the failure by officials (even ones sympathetic to a savings deficiency story) to identify areas of policy where govts are systematically skewing our national savings rate down relative to those in other countries. As a central planner one could try to boost national savings, or lower population growth. My conclusions follow from a fairly standard neoclassical analysis of looking for the policy intervention that caused the imbalance, and removing that at source. No one seriously disputes that a large immigration programme is a policy intervention. But elite opinion is committed to a belief in the benefits of large scale immigration programmes, so faces an enormous intellectual and emotional hurdle to get to my conclusion.

In an ideal world, there would be a major rich cross-country across-time study to help shed fresh light on the story of the determination of interest rates. Must people I’ve talked to, including those much more research oriented than I am – are reasonably sceptical that any such studies will ever show anything very conclusive (and perhaps especially not about this one episode in world econ history – the last 25 years’ failure to converge in NZ.

LikeLike

I accept your hypothesis – I think if the NIIP risk premia thesis were correct, we would hear traders and sell side brokers talking about it more. I was more concerned that perhaps the RBNZ had thought that immigration actually thought immigration reduced wage pressure, or that they kept changing their mind about it. Flicking through some of the Governor’s recent speeches, I detect a “on the one hand, on the other hand” attitude to the effect of immigration on both house prices and inflation.

LikeLike

Thanks Blair

I spelled out the story mostly for other readers rather for you.

But yes there was a bit of RB flip-flopping on the subject over the last 18 months. But even then they were arguments about the specifics of the current situation, rather than the general nature of immigration pressures. There was, for example, an argument that lots of the carpenters coming to Chch might be young and single, putting less pressure on resources (and providing more labour supply) than the typical migrant (at the other extreme, the parent visas). There may be a little to that – composition does matter to some extent – but their own published empirical research is pretty clear that the average effect of a shock to migration is to (net) increase demand and increase interest rates.

LikeLike

There is a lot of anomalies in NZ statistics numbers that is not clearly understood by our economists(perhaps intentionally) and then these become headline news.eg

1. Net PLT gains of 62,000 but no one mentions that most of the net increase is from international students, returning kiwis and foreign workers for the Christchurch rebuild leading to calls for less migration and the public questioning why the government does not respond. Thhe answer is simple. The government cannot respond because the net increase is not from real permanent resident migration but from the other 3 variables.

2. $62 billion of property investment debt included with NZhousehold debt and compared with NZ household disposable income but excluding tenants income to give a erroneous 160% debt to income ratio which was headline news for years and then oooops RB corrects the $62 billion error and the debt to income ratio drops to 100%. Who in their right minds leaves out the income from an investment debt?? Apparently it is ok for economists in NZ to do that.

3. Reliance on NZ Household disposable income when there is clearly almost 2 million people that potentially have incomes outside of NZ borrowing and buying properties in NZ. Not factoring that almost 40% of our population is migratory. NZ household disposable income is so badly skewed it is incredible anyone in their right minds even would place reliance on it.

4. Poor savings?? $192 billion is not poor savings It is incredulous that QC would even question listed share value as if the whole $49 billion would be liquidated in an instance. If you question the value of savings by NZ Households then you may aswell write down the trillions of dollars in the savings of every other nation and NZ would still shine pretty well.

5. Trying to justify a net debtor position by bringing in corporate debt is also poorly understood. Corporate debt is funded by the equivalent assets and the interest obligations are more than adequately covered by corporate earrnings. If corporate debt is a problem these businesses would be out of businesss. The biggest risk to a business is not competition. It is the RB when they get trigger happy with the OCR.

LikeLike

6. The OCR drives the key benchmark 90 day bank bill rate. The RB drives the OCR. You can look at the entire history of the 90 day bank bill rate and you would find it is almost a mirror image of the OCR. Yes, I would agree that at some point where NZ starts a war like Russia then the OCR would cease to influence interest rates because the rest of the world would view NZD as high risk. No one over the last 20 years would consider the NZD high risk even though NZ economists try to justify our high interest rates with that glib comment.

LikeLike

I’m not really sure of your point. All statistics have their pitfalls and most are useful for particular purposes. As we gone over repeatedly, PLT numbers are more or less relevant for the short-term impact on demand, but they are not that relevant as a reflection of govt policy on immigration. Other – approvals etc – data are. I could make the same sorts of comments on almost all the points in your list.

LikeLike

…true that ggs: I was somewhat playing devils advocate!! Though, I struggle with the idea NZ is a nation of savers when – on a stock or flow basis – the country remains reliant on the rest of the world for financing. I guess my basic point is that a consolidated balance sheet is more vulnerable when debt is a higher proportion of the financing mix, which, in the case of NZ, is mainly reflected via the slug of offshore funding within the bank sector. True, it is hard to see a ‘shock’ that will shake confidence in the NZD and our history of being a stable democratic country must look fairly attractive at the moment. But then again, ‘shocks’ are easier to spot in hindsight…!

LikeLike

The point is NZ economists have painted NZ to be such a bleak and debt trodden economy and that we are borderline bankrupts and we have too many people at a paltry 4.2 million. What this does is create wrong investment decisions. A company that is struggling to survive versus a company that is growing has different decision criteria. Survival means to cut costs to the bone and every cent goes to paying off debt. A growing company is prepared to take on debt to allow investment in infrastructure and that allows revenue growth and productivity gains.

Our economists deluded perception of poverty means we are always in survival mode and we do not borrow and invest in infrastructure that would enable growth and productivity. People are people. There is no difference between a imported migrant and a New Zealander that becomes a immigrant in Australia. Only one generation is a migrant because the 2nd generation is kiwi born so your immigrant statements lack integrity.

These are RB and NZ Statistics numbers. I have have shown why these do not support NZ economists contentions.

LikeLike

Businesses invest on their perceptions and experiences of opportunities, risks and markets. For whatever reason, in New Zealand they don’t do much of it (business investment as a share of GDP has been persistently low for decades). I’ve put forward a hypothesis for why that is. Others have different views. But I’m sure none of the people actually making investment decisions pay much attention in making those decisions to big picture economists. And nor, speaking as one of those economists, should they.

LikeLike

QC, I actually shared the very same perception that NZ Households was highly indebted because I used to read glib poorly researched comments by NZ economists. One day I just thought I would look up some of these highly indebted numbers and instead found that 33% of NZ households are completely free of debt, That is a staggering 400,000 NZ household property debt free. NZ Household debt in total including all consumer credit card debt was only $158 billion.

So I continued and thought we have poor National savings but lo and behold our cash savings in the bank totalled $143 billion. Add that $49 billion invested in listed shares and we came up with liquid assets of $192 billion well in excess of all NZ Household debt. Ok so we add another $62 billion in Property investment debt and that still brings our debt level to $220 billion, still very respectable given savings of $192 billion. But if bring in the asset value plus the savings, NZ households have a trillion dollars net wealth. This net trillion dollar wealth does not include all that Maori community land or any crown owned land like the $10 billion in HNZ properties.

So where does this perception that we are heavily debt burden comes from and I read a RB comment in tiny print that NZ household debt is very low but the RB was concerned that NZ Household disposable income does not look like it can afford to service the debt.

Then I started to look at NZ Household disposable income. Firstly you cannot get a home loan if you cannot afford to service the interest. When you borrow from a bank they will check your income very thoroughly. Lose your job and they pull your loan within 6 months. Therefore it cannot be correct that NZ household disposable income is accurate. Then I realised that NZ has a million migrants to replace the million New Zealanders that live outside of NZ. There are at least 2 million people whose possible overseas income is missing from NZ Household disposable income. 2 million out of the normal 4.2 million that NZ statistics uses would introduce a 40% outlier. I have lots of mates living around the world and they do buy and borrow in NZ, their incomes are not factored into NZ household disposable income. I have been working with a number of well heeled migrants, they all have companies and businesses overseas with massive overseas incomes. eg, Deyi Shi who bought out the Hotchkins mansion for $39 million and borrowed $20 million to acquire the property with a NZ income of $300k. This one migrant would have blown NZ Household disposable income out of the water.

LikeLike

….ggs! I’m replying here to your post of 11:20 (great stuff indeed, thanks!) as I can’t see a reply button there which no doubt reflects my IT skills!! I’ll think on as I hear you and indeed, statistics can often revel more than they hide. I still think (but the picture isn’t clear!) the distribution of income, assets and debt across the population/sectors plus the role of financing (i.e. who/where the finance coming from) matters when reflecting on current macro trends. And, more broadly on the ‘debt burden’ issue, I have yet to find a clear explanation re what drives the upper limit of aggregate debt accumulation for a given currency area: ‘it depends’ seems to be the case (e.g. debt/GDP ratios of Japan v UK v China v NZ) – if you / anyone has any thoughts, let me know! cheers

LikeLike

whoops “….hide more than reveAl”: what a plonker I is!

LikeLike

New Zealand is an external debtor because it is cheaper to raise funding offshore if you look at household savings over the last 60 years you will find they that we are net savers to the tune of 5 percent of our annual income. We only really had negative household saving for short period in the 2000’s. Economists constantly confuse this issue in the media.

LikeLike