After The Treasury released their file note of that 24 February meeting between the Reserve Bank, Treasury, and the Minister of Finance (full copy here) a few people got in touch directly about a couple of aspects of what was written there, and what I’d made of it.

The file note indicated at one point that in the middle of the Funding Agreement discussion “The Governor left the meeting”. A couple of charitable people (not typically Orr allies) suggested that perhaps I was overinterpreting things to suggest that he’d walked out. I think they were pretty readily convinced that this was a very unlikely interpretation (in a meeting of which the Minister of Finance had already said that it had been clear to her that “emotions were running high”).

Former academic and now consultant economist Martin Lally then sent me this rather neat piece. Some of the non-economists among you might roll your eyes and suggest ‘that’s economists for you”, but I thought it was a nice example of the use of the technique to help discipline thinking.

Seems like a great opportunity to apply Bayesian analysis.

The hypothesis (H) is that Orr stormed out of this meeting. Your background data concerns his type of behaviour on other occasions. Suppose this alone leads you to the view that H has a 10% chance of being true. This is likely to be too low. The odds on H being true are then at least 1/9.

The next piece of evidence is the anonymous information about Orr’s behaviour at the meeting. I sense that you think this evidence would be much more likely to arise if H were true than if H were not true; maybe five times as likely? So, the Likelihood ratio for this evidence is 5. The odds on H being true now rise from 1/9 to 5/9.

The next piece of evidence is the meeting at Treasury a few days before the meeting in question here, on the same funding issue, after which Quigley apologised on Orr’s behalf for Orr’s behaviour. Since it was on the same contentious topic, this evidence seems much more likely to arise if H were true than if H were not true; maybe five times as likely. So, the Likelihood ratio for this evidence is 5. The odds on H being true now rise from 5/9 to 25/9.

The last piece of evidence is the minutes of the meeting in question, which reveal that Orr left during discussion about the funding issue, which Orr had very strong feelings on. If H were true, this evidence or something even more damning would be almost certain to arise because the minute taker would be most unlikely not to have recorded that Orr left. Say a prob of 0.95. If H were not true, the minutes could still have recorded him leaving at the time he did but in that case it would have to be due to quite extraordinary information he had just received that demanded his immediate departure from a discussion he would otherwise have strongly desired to be present for. It could be news of his house burning down or a serious injury to a loved one. These things happen but it would be extremely unlikely to have occurred in the 45 minute time slot in question. So, if H were not true, the prob of his departure from the meeting at this time is close to zero. Suppose events like his house burning down etc happen once every 6 months, so 1/180 chance of it happening on that day and, if on that day, 1/10 of it happening during the 45 minute duration of the meeting on that day, so 1/1,800 of it happening during the meeting, which is 0.0005. So, the Likelihood ratio for this evidence is about 0.95/0.0005 = 1900. The odds on H being true now rise from 25/9 to 47,500/9, so the prob that H is true is now 47,500/(47,500 + 9) = 0.9998, i.e., 99.98%.

So, with all this evidence, it is virtually certain that Orr stormed out of the meeting. This nicely illustrates the power of Bayesian analysis.

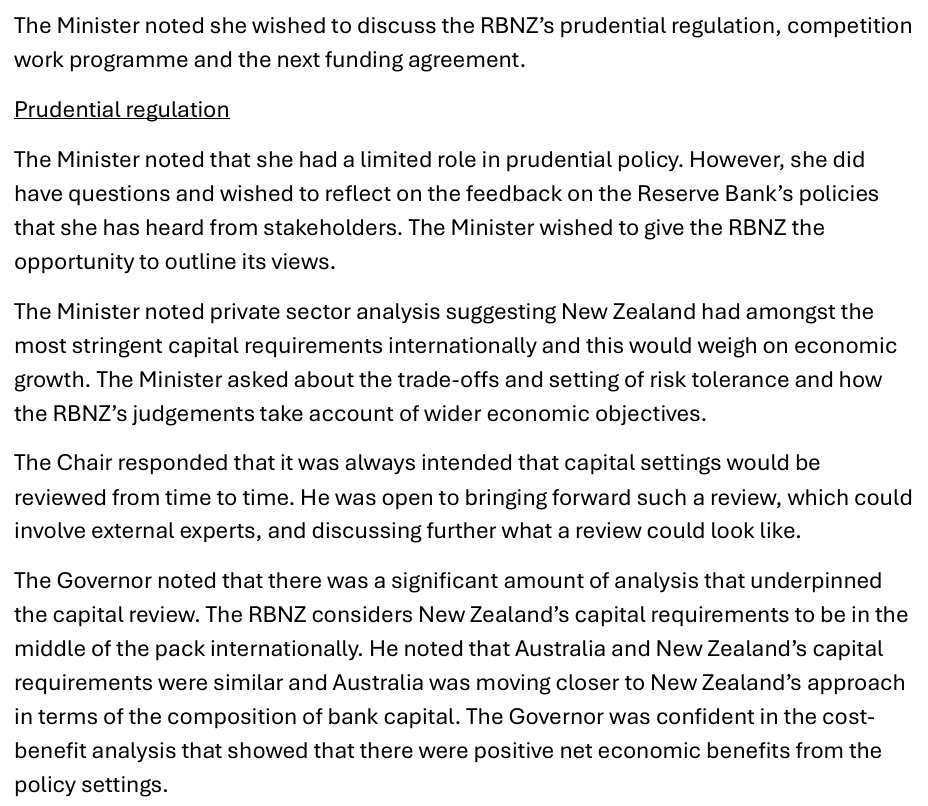

A few other people got in touch about the earlier part of the meeting, on banking regulation and competition matters. This part of the meeting was attended by Reserve Bank Deputy Governor Christian Hawkesby, whose day job at the time was financial stability, supervisory and regulatory etc issues (and he left the meeting when his item ended, thus missing the – apparent – fireworks).

The relevant bit of the file note was this

It is pretty clear from that that the Minister of Finance wanted a review. Perhaps she didn’t say it directly, but it is the clear implication of what is recorded in those first two paragraphs, and Quigley clearly recognised it as such, noting (folllowing the Minister’s remarks) that he “was open to bringing forward such a review….and discussing further what a review could look like”.

Why raise this now? Because Hawkesby is currently the temporary Governor, and supposed in some circles to be keen on getting the permanent job. Even if he doesn’t want to be permanent Governor, he is the deputy chief executive of a major government agency and a statutory appointee to the Monetary Policy Committee. Those who got in touch earlier this week reminded me that a few months ago (8 May) Hawkesby had been asked at Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee about this meeting. Radio New Zealand’s report is here.

The first part of Hawkesby’s remarks seem fine

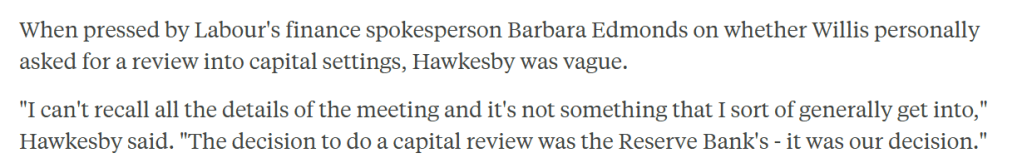

But then FEC was told this

The meeting had been only two months previously, it had been only a 45 minute meeting (of which he was only there for half an hour or so), on matters he had direct responsibility for, and the meeting itself has to have stuck in his mind given the role it seems to have played, within days, in the Governor’s departure. What’s more, surely you’d normally expect that coming out of a meeting like that there’d have been some sort of file note (especially when his boss and the board chair had appeared to be singing from different song sheets) or even an email to his direct reports in that area, and if he was really in doubt as to what went on I guess he could have asked Treasury for their file note. And yet we are supposed to believe that whether or not the Minister had requested (or only strongly implied) that a review should be undertaken was “not something that I sort of generally get into”. It reads a lot like misleading Parliament – in much the same way Orr had done repeatedly, often with Hawkesby in the room.

To be clear, I’m sure he is quite correct that “the decision to do a capital review was the Reserve Bank’s”, but in much the same way that the Governor’s decision to resign was a “personal decision” – at one level it was, but he was clearly prevailed on, pressured to go. Under the law as it stands Willis couldn’t directly compel the Bank to undertake such a review, but it will have been the less bad choice for them (she could have changed the legislation or commissioned her own review for example). And it was also a time – the end of March when the final decision to do a capital setting review was announced – where it probably will have suited Quigley and Hawkesby not to have been difficult; Quigley wanted his medical school, and Hawkesby may well have wanted to be made permanent Governor. The review would not have happened when it did without the Minister’s lead.

(And, to be clear, I don’t think that is a problem. As I’ve noted repeatedly, I think the law should be changed so that big picture prudential policy choices are made by ministers, with the Bank acting as (a) expert advisers, and b) implementing agents. I don’t think the Minister’s involvement here is inappropriate – whatever one’s view of actual capital settings – but really senior officials should not be misleading Parliament. And when they do, and when they sit silent while their bosses mislead Parliament, they really should not be serious contenders for high and very powerful office. Misleading Parliament is supposed to be a serious matter, and if MPs seem to have given up bothering over much (except when it suits), the rest of us should still insist on higher standards of integrity.

It is, in addition, supposedly one of the Reserve Bank’s own values

But perhaps those are just words. The actions at the top certainly haven’t aligning with the words for some time.