Back in the early days of this blog, I illustrated how for advanced countries as a group cumulative growth in real GDP per capita in the period since the peak of the last cycle (2007) to 2014 had been no better than that in a comparable seven year period from 1929, during the Great Depression.

Here is an updated version of the chart I ran then for all the OECD countries

The median growth rate – o.22 per cent in total over seven years – is so small as to be almost invisible on the chart.

And here is the comparable chart, using the Maddison database of historical estimates, for the years 1929 to 1936

I wouldn’t want to make much of the differences in the median growth rates – given the imprecision of many of the historical estimates, and the likelihood of revisions to the more recent ones. I was more struck by the lack of any material real GDP growth per capita in either period.

The Great Depression is seared in historical memory – and whole generations of politicians came afterwards telling themselves and voters “never again”. It is too soon to know whether the most recent period achieves the same permanent imprint on historical memories. Perhaps in part it will depend what comes next. But I’ll be a bit surprised if this episode has quite the same impact. The Great Depression hit popular consciousness particularly hard because unemployment rates in so many countries rose very high, and stayed high for a long time, and in an age when government income support for those unemployed was typically less generous than it is today.

There aren’t (at least that I’m aware of) any consistent cross-country estimates of the unemployment rates in the 1930s. But in most countries, the increases in the unemployment rates were very substantial (in the US, the unemployment rate is estimated to have peaked well above 20 per cent, and remained high for years).

By contrast, here is what has happened to advanced country unemployment rates in the last decade or so.

Whether one takes the median OECD country or, say, the total for the G7 countries, there was an increase in the unemployment rate of around 2.5 percentage points, which has been substantially reversed over the subsequent years. Unemployment rates are typically around where they were in 2006. There are still awful cases – Spain and Greece still have unemployment rates in excess of 20 per cent – but the defining character of the last few years has not been very stubbornly high unemployment rates.

What really marks out the last decade – and contrasts it with the 1930s – is how poor the productivity growth has been. Without productivity growth, one can still end up with plenty of jobs, but they tend not to offer much in way of wage increases.

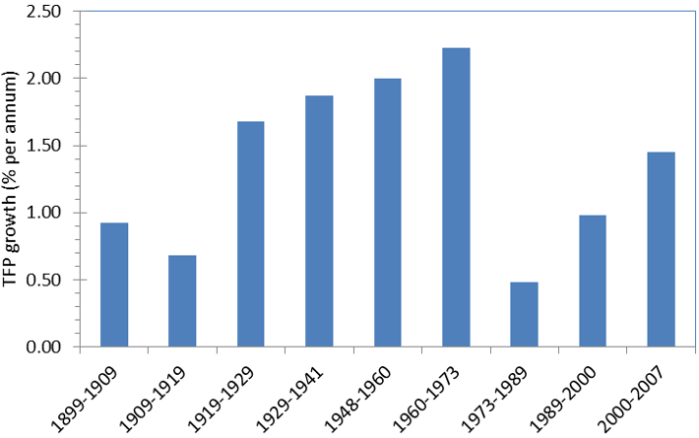

I’ve drawn attention previously to the work of US economic historian Alexander Field, who devoted a book to illustrating the very strong productivity gains (TFP) that the US had achieved in the 1930s. A few weeks ago, I saw a nice summary of a new study by some other economic historians. On the basis of their new work, they no longer see the 1930s as the period of fastest TFP growth in US history, but it was still very strong – reflecting rapid technological and managerial innovations. Here is the key chart.

Figure 1. TFP growth in the private domestic economy, US, 1899-2007 (% per year)

By contrast, here is a picture that uses John Fernald’s (FRBSF) business sector TFP estimates for the US over the last 25 years.

Business sector TFP growth is typically faster than for the entire economy, but for the last 10 years Fernald estimates average annual growth of just over 1 per cent, dramatically slower than the 7 per cent average growth over the previous 10 years.

The slowdown in productivity growth isn’t unique to the US – indeed on some measures, the US has done better than most – and was becoming apparent in the data (again, not just this dataset), if not in the public consciousness, before the great recession of 2008/09 and its aftermath.

The contrast with the 1930s is striking. That was, overwhelmingly, a failure of demand and of the global monetary system, and as those constraints were removed, the underlying lift in productivity supported a recovery in investment. For the US, for example, post-war per capita GDP is on the same growth path as it had been pre-1929: output wasn’t permanently lower.

What about the current situation? Taken together, falling rates of population growth and falling rates of TFP growth materially reduce the volume of investment that is likely to be required, and profitable, at any given interest rate. Add in apparently high desired savings rates around the world, and it is hardly surprising that real interest rates have fallen away so much. Add declines in inflation expectations to the mix, and it has reinforced the decline in nominal interest rates. The problems are mostly structural in nature, but they have been amplified by the reluctance of central banks to do what is required to keep inflation (or other nominal measures) up around target, in turn driven by a constant focus on a desire for “normalization” and a focus on some sense of where real interest rates “must” (in some sense) be in the very long term. The reality, and perceptions, of the near-zero lower bound haven’t helped in many countries.

I’m pretty confident that in the longer-term real interest rates around the advanced world will be positive – land is still fertile, as is the human imagination (so there will be a flow of new innovations and opportunities. But there is no guarantee of such positive real interest rates in any particular decade (any more, in a New Zealand context, than there is a guarantee that our real interest rates will converge with those of “the world” in any particular decade). It seems likely that some mix of lower global savings rate, higher birth rates, and structural reforms that create a better climate for productivity growth and investment are likely to be required to put the world economy on a better path – one that, inter alia, might put us back on a path that supported more “normal” levels of nominal and real interest rates. But those interest rates will be an outcome of a successful overall policy mix, not an intermediate target in their own right. Monetary policy – here and abroad – in recent years has come too close to treating them as an intermediate target, rather than focusing on, and responding to, the data flow.