The new Chief Ombudsman, Peter Boshier, had some encouraging comments in his interview about the Official Information Act with TV3’s The Nation that was broadcast over the weekend (transcript here).

In some cases, they involved walking back some earlier surprising comments. In an interview with Fairfax only a couple of months ago Boshier said that, despite the huge backlog of complaints and very long delays

Turning to parliament for more resources and money wasn’t tenable, he said,

But now he tells us that he has a request before Parliament for more budget resources

That request should fall on receptive ears. In their recent financial review of the Office of the Ombudsman, Parliament’s Government Administration Committee noted that, despite the efforts of the previous Chief Ombudsman to improve efficiency

Nevertheless, we believe the Office is under-resourced and over-worked, and would benefit from additional resources.

Boshier talks in a way which suggests a commitment to making the Official Information Act work in a way that respects, and gives tangible form to, the stated purpose of the Act

The purposes of this Act are, consistently with the principle of the Executive Government’s responsibility to Parliament,—

(a) to increase progressively the availability of official information to the people of New Zealand in order—

(i) to enable their more effective participation in the making and administration of laws and policies; and

(ii) to promote the accountability of Ministers of the Crown and officials,—

and thereby to enhance respect for the law and to promote the good government of New Zealand:

and its Principle of Availability

The question whether any official information is to be made available, where that question arises under this Act, shall be determined, except where this Act otherwise expressly requires, in accordance with the purposes of this Act and the principle that the information shall be made available unless there is good reason for withholding it.

He spoke several times of his view that we should think of it as a freedom of information act (the title used in several other countries), noting

I think that there should be a premise that why don’t we make information available? Let’s start with the default position of ‘why not?’ instead of ‘why should we?’

Although he didn’t mention it, greater use of pro-active release of material by ministers and agencies would be consistent with this sort of approach (and typically cheaper for agencies too).

Boshier is planning to meet with all the political parties in Parliament to discuss his expectations and aspirations, and the standards to which he will be holding government agencies. It is though perhaps a little disappointing that instead of meeting with the Prime Minister and/or the Minister of State Services, he will only be meeting the Prime Minister’s chief of staff.

But his goals seem good. He says he isn’t going to tolerate agencies going against the spirit of the Act in respect of meeting deadlines – using all 20 working days, rather than releasing material as soon as reasonably practicable (the statutory requirement). That sounds good, although I had a conversation a few weeks ago with one of his staff that suggested that that attitude has not yet seeped all the way down the organization – or at least that staff can still be too trusting of agencies and their excuses for delays.

In one concrete measure,

when we get a complaint or an official information request and we ask an agency’s view, we will give them 28 days. I think it’s too long, so I’ve started to a) cut down that down to something like 14

And he is hoping to use any additional resources to clear out the current backlog (650 cases more than 12 months old) and get the Office onto a basis in which 70 per cent of complaints can be resolved within three months, and all complaints dealt with in 12 months. If that can be achieved, it would be a huge step forward (but would, no doubt, prompt more complaints, since people might believe a complaint might actually make a difference, in timeframes that matter). There was talk of greater use of ADR techniques, which sounded interesting, but there were no specifics.

Boshier also announced that

as of the 1st of July, we intend to move towards publishing what I’ll call league tables. We pretty much know who are really good compliers with the act and those who are not, and probably it will be good for the public to know that as well.

It sounds very well-intentioned, but I’m a little skeptical. We will need to see the details of what is planned, and the Office of the Ombudsman will need to be willing to revise those details in the light of experience.

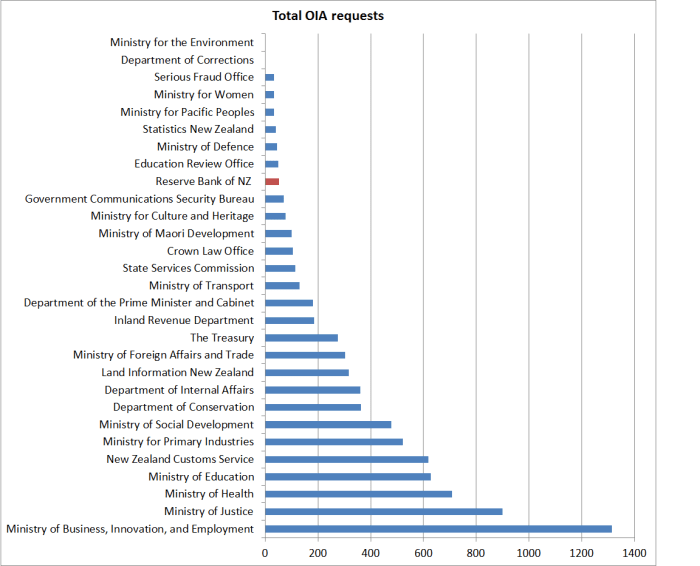

The Official Information Act, and its local government counterpart, covers a huge number of organisations (including every school Board of Trustees) most of which probably get very few requests (or at least very few that they consciously treat under the provisions of this legislation). I wonder which organizations the Office is planning to cover in its league tables?

Perhaps a list that encompassed each government minister, public service departments, non public service departments, the Reserve Bank, and some of the larger crown agents, autonomous crown entities, and independent crown entities might be a good place to start.

But perhaps more importantly, what are they planning to measure and report? If league tables are to be used to heighten pressure on agencies, and yet those league tables can be easily or materially gamed, they could be almost worse than useless.

Much of what we should care about in respect of compliance with the Act isn’t easily measured in ways that are amenable to league tables. It is about compliance with the spirit and principles of the Act.

It might be useful to know how many OIA requests have been responded to within 20 working days, and track those proportions for each agency over time, but…..if many requests are of a sort that should be turned round in three working days, and others are genuinely complex, how is that going to be reduced to a useful league table?

At present, when agencies respond to occasional requests about how many OIA requests they receive they have no particular incentive to gloss the numbers. Technically, any request to any agency for information, of almost any sort, has to be treated as if it were explicitly a request under the OIA, but few count every approach. League tables, designed to exert pressure, change the incentive.

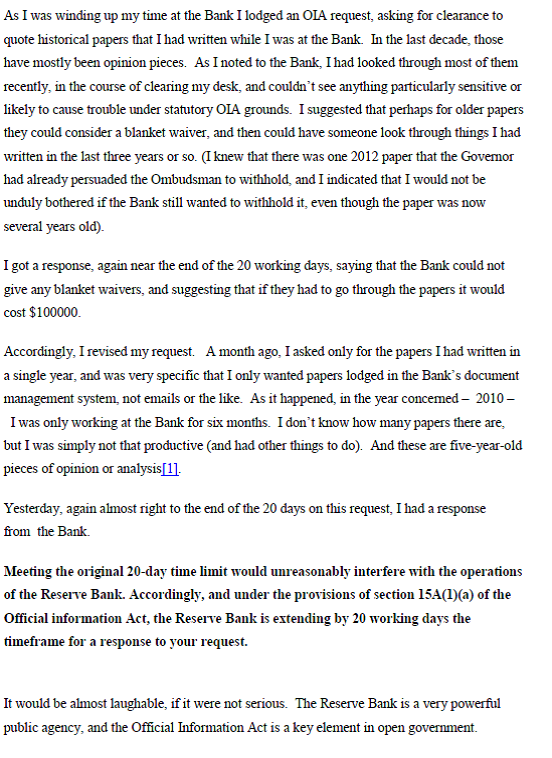

Take the Reserve Bank as one illustrative example (and not to criticize the Bank, it is just the agency I know best). The Bank generates a considerable volume of financial statistics and publishes a lot of material on its website (although, like many websites, unless you are familiar with the site specific material can sometimes be hard to find). The Bank gets a lot of simple requests re data, simply dealt with in a very quick email response, or answer to a phone call. Those requests aren’t included in the 51 requests the Bank reported receiving last financial year. But a league table could easily capture all these requests, and the quick response times (which are welcome), without shedding any real light on the issues of concern around the handling of the more contentious OIA requests.

Or take the Governor’s press conferences, at the release of the MPS and FSR. As far as I can tell, each question is technically a request for information, covered by the Official Information Act. Each answer is given within seconds of the request being made. Over a full year, that would be easily another 100 requests lodged and expeditiously dealt with, without shedding any light on how the Bank handles requests for material it doesn’t want to release.

I’m sure those who know other agencies or departments in detail could readily come up with similar opportunities to game the statistics and any league tables.

It is good that the Onbudsman reckons he knows who the good performers are, and who the bad performers are, and that he wants to let the public know, but I suspect he is going to have a very hard time reflecting those assessments in any sort of league table. This is mostly about attitudes, and they are fairly easy to spot, but hard to attach a number to.

Finally, the Ombudsman was asked about agencies charging for OIA requests, and specifically about the stance of the Reserve Bank. He avoided the specific issue of the Reserve Bank’s approach, but commented more generally

if we were to call this a freedom of information act and not an official information act, it gives the right tone. There should be an assumption that you can get information in a freedom way – that is without cost. That’s my starting point.

I do not support charging as a general rule.

That is welcome.

It is, however, quite a change of stance over only a few months. In that Fairfax interview in January he had said

“I think the Reserve Bank’s response is actually very fair. When I looked at it I couldn’t fault it. As a statement of principle it was perfectly fair and it’s one to which I subscribe,”

And, as the Reserve Bank itself revealed, the Ombudsman’s office had advised the Bank, as recently as November, that

Ms Kember [Principal Adviser in the Ombudsman’s Policy and Professional Practice Advisory Group] said that the Ombudsmen generally consider both that it was reasonable for agencies to charge in accordance with the guidelines and that the charges imposed within those guidelines are likely also to be reasonable. She said it is surprising that more agencies don’t make greater use of charging as one of the tools available to manage their overall workload and processes for responses where this would be helpful.

November was, however, before the new Ombudsman had taken office.

The Chief Ombudsman’s heart appears to be in the right place, and the direction of his comments yesterday is very much one that I would support. The Office of the Ombudsman has some legal powers and should have some moral authority which he may be able to use to lift the compliance of government agencies with the letter and spirit of the Official Information Act. His predecessor was reluctant to use that authority. But much also depends on political leadership. There were some encouraging comments in response to Boshier’s interview from the Greens, but are the leaders of the National and Labour parties likely to treat this an issue that matters?

In the end, the Ombudsman can go only so far. As I’ve pointed out previously, the relevant provisions of the Official Information Act itself appear to allow a more active use of charging than is envisaged either in the government guidelines on charging, or in the comments yesterday from the Ombudsman. Good practice – few agencies actually do charge – need not be as stringent as the provisions of the Act allow, but it might be timely to review the statutory provisions to buttress a sense, now apparently shared by the Chief Ombudsman, that official information should largely be available freely, in both senses of the word.