I got home from Papua New Guinea at 1:30 on Saturday morning and by 3:30 yesterday afternoon I’d finished Grant Robertson’s new book, Anything Could Happen, and in between I’d been to two film festival movies, a 60th birthday party, and church. It is that sort of book, a pretty easy read.

In some respects, that is to the credit of the author. It is pretty well written (although not exactly the publisher’s description: “beautifully written”). I almost always like the “early life and upbringing” chapters of autobiographies and this one was no exception. That is probably a mix of the various laugh-out-loud funny anecdotes,

the fact that there were certain similarities in our childhoods (heavy church orientation, and I too was six when Mum and Dad told us we were changing islands so Dad could pursue his sense of call to the ministry), and the discovery that my wife and kids are (distantly) related to Grant Robertson (former Minister of Finance, Downie Stewart, who resigned in 1933 on a key point of policy difference, is a common relative).

Two other sections will stick with me: the treatment of his father’s betrayal of his family and his employer, culminating in 18 months in Dunedin prison is quite moving, and something no one would wish on any teenager, and Robertson’s pretty severe physical debilitation by the second half of 2022, that meant that when Ardern first indicated (in the September quarter of 2022) that she might step down, Robertson stepping up really wasn’t a viable option.

For the rest, unfortunately, I imagine it is the sort of book many of his mates and Wellington Central supporters will want to have on their shelves. Perhaps his staff at Otago too.

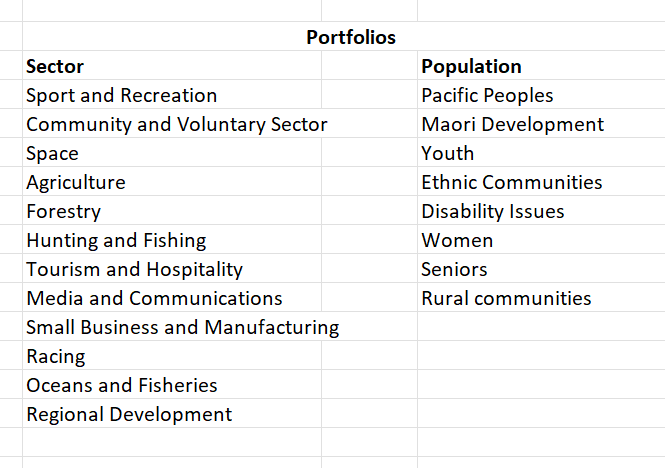

But you will search in vain for any serious insight or reflection on the politics, politicians, or policies of the 20 years or so in which Robertson was first a staffer, then an Opposition MP, and then a senior minister and close confidante of the Prime Minister. He was Labour’s finance spokesperson and Minister of Finance for, in total, just under 10 years (Minister for six of them), and had been Labour’s spokesperson on economic development for a while before that. He ended his political career having held only one substantial portfolio – Finance – and yet in this book you will look in vain for any distinct Robertson perspective on events or issues or institutions or individuals relating to that portfolio or (mostly) for any perspective at all.

As just a small example, back when Robertson became Opposition finance spokesperson his big project was something called the Future of Work, Danish “flexicurity” and all that, (an old post on some of that here). There was serious work done, and yet the book contains just one mention of that project – a mention of getting agreement from Andrew Little (newly elected leader) that he could do it.

But step back a bit further. Robertson shifted over to the political side (from MFAT) in the Clark government, stepping in first to become political adviser to Marian Hobbs before shifting some time later to the Prime Minister’s office. Robertson obviously has and had great affection for Hobbs, who wasn’t one of the shining stars of that government. We get plenty of the amusing malapropisms to which Hobbs was prone under pressure, but little of what made her tick. And if she is now a name many readers will barely be aware of, the same can’t be said for the big players of that government – Clark, Cullen, even Anderton, and of course behind the scenes Heather Simpson. Do we learn anything about them from this book (written by someone who was actually a student of political science, before himself becoming a senior player)? Barely at all.

And if we get that Robertson really really didn’t like, or have any time for, his rival (and Labour leader at the 2014 election) David Cunliffe – and to be fair, there seem to be many people who share that view – and wasn’t too keen on Charles Chauvel (younger readers can look him up) either, that is about it from his side of politics, and even those critical comments are less insightful than conventional and one-dimensional. Robertson served as a senior minister for six years, in a government with lots (and lots) of Labour ministers, losing them by the end at a rate of not much less than one a month. But there is no critical evaluation of any of them (not Stuart Nash, not Kiri Allan, not Kelvin Davis’s time as deputy leader), and not even any insight on what made key players tick. My one takeaway about Jacinda Ardern was learning that she’d once been hospitalised with the same obscure 19th century condition that had once put my wife in hospital on the other side of the world.

And if you suspect that that silence might have had to do with not wanting to risk upsetting anyone in the Labour family, he isn’t really any better on people on the other side of politics (other perhaps than a few interesting comments on Winston Peters in the 2017-20 Cabinet). Luxon gets three mentions, only two from his time in politics, and one of them was simply a mention that he (Luxon) had suggested Robertson (as caretaker Minister of Sport) should go the Rugby World Cup final in 2023, and Nicola Willis – despite facing him as National’s finance spokesperson through the last 20 months of his term and the election campaign – gets no mention at all (critical or otherwise). You’d have thought that a shrewd and experienced operator like Robertson would have had some perceptive, witty, and perhaps even unfair, observations to make. But apparently not. Perhaps he just wasn’t a close observer of people?

And it isn’t just politicians. If productivity (or cognate words/ideas) gets no mention, neither does the Productivity Commission – whose fate Robertson sealed with his appointments in the government’s second term. There is barely any mention of the advisers in his office, whether the political ones or the Treasury secondees and almost nothing about Treasury at all. Gabs Maklouf, whom he inherited, gets just one mention – around the “budget leak” in 2019 – and Caralee McLiesh also rates only a single (and entirely non-insightful) mention. There is nothing about her recruitment – an overseas person with no macro experience – or contribution (Covid or otherwise) or personality or role in the institution. You will learn precisely nothing about Treasury itself (not even Robertson’s views of it) in this book.

And while I’m enough of a junkie that I was always going to buy the book, I was perhaps most interested in what Robertson would have to say about the Reserve Bank in general and Adrian Orr in particular, the more so since Orr was no longer the incumbent. The short answer is almost nothing.

Orr appears twice in the index. The first mention relates to his appointment at the end of 2017. Robertson suggests that on coming into office he did not want an RB insider to become Governor. Which would be fine except that by then (a) Wheeler had refused to seek reappointment, b) his deputy, Spencer, was serving as a – dubiously legal – acting Governor and planning to retire as soon as a substantive appointment was made, and c) I’m pretty sure the other senior RB potential contender, Geoff Bascand who had indicated that he had applied, had already been winnowed out before the change of government. Anyway, Robertson’s only observation is that he wanted to know whether Orr would be open to the reforms Robertson’s envisaged (an MPC, with externals), which Orr was.

And the second reference was to that odd episode in late 2020 when Robertson overruled the Bank and inserted in the MPC’s Remit a clause that (loosely) required the Bank to assess the impact of its policy measure on house prices (without having any particular implications for policy). It was, we are told, “the only time in my term as Finance Minister that I clashed with Adrian Orr as Governor”. And that’s it.

On the substance, that comment in the previous paragraph is pretty damning (if true). The Minister never raised concerns about Orr’s behaviour (of which there were many documented public episodes), the Minister never expressed concern about the $11 billion Orr and the MPC lost taxpayers, he never expressed concerns about FEC being misled, he never raised concerns about inflation being let to run rampant? And did he really never have the feisty Orr overstep the mark, even slightly, in his (Robertson’s office)? And, of course, we learn nothing of his sense of Orr – even with just with the benefit of hindsight – we get no sense of why Orr was reappointed (over the objections of Opposition parties, when Robertson himself had amended the legislation to require consultation), nothing about that weird ban on having experts appointed to the MPC, let alone anything about the wider reform of Reserve Bank governance (and the underpowered Board he appointed) or even such significant structural reforms as deposit insurance.

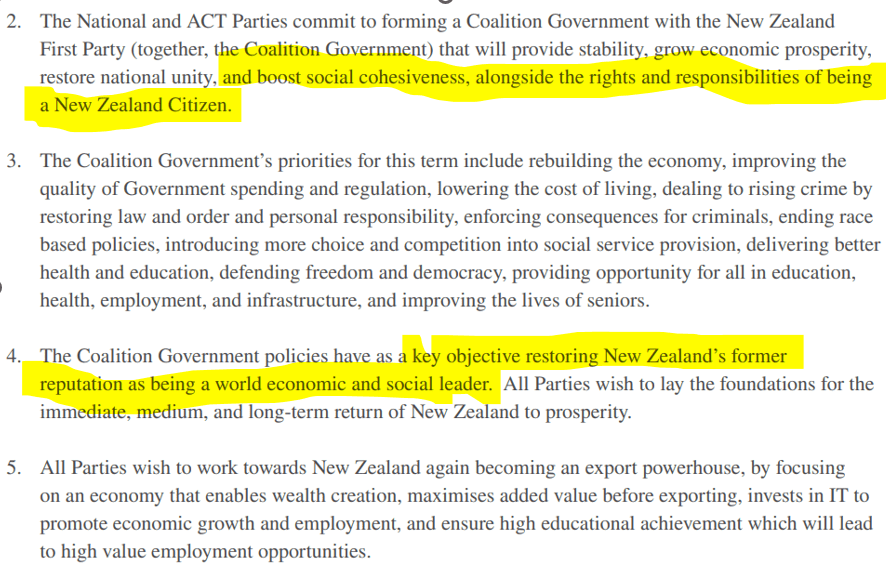

And, of course, there is nothing at all on the structural fiscal deficit Robertson bequeathed to his successors (yes, even on PREFU numbers which included quite a bit of last minute vapourware promises about future fiscal chastity and sobriety). Not even a rueful reflection on the contrast between those Budget Responsibility Rules he and James Shaw had launched (to the upset of the left of their own parties) back in Opposition in March 2017 and the way it all ended. And nothing at all on what role Treasury advice and (poor) forecasts played.

It is a shame. There was some good things done by Robertson as Minister of Finance. He was finally willing to grasp the nettle and reform the governance of monetary policy and of the Bank more generally (I was a discussant at the event in 2017 when he launched that policy and the associated post was headed “Grant Robertson made my day”). Not everyone was a fan (the RB wasn’t) but I thought, and think, that deposit insurance was an appropriate second-best reform. But even on RB matters, execution and details left so much to be desired. Perhaps Robertson can’t really be blamed for Orr in late 2017 (he was new, and had to appoint someone the Quigley-led Board wheeled up), but he can for most of what followed – the bloat, the loss of focus, the personal behaviour, the disempowered MPC (lightweight appointments, never heard from), and so on…..all culminating in that stunning exit on 5 March this year.

There aren’t many good books in New Zealand on policy and politics. You’d have thought (I did – I was looking forward to the book) Robertson would have been capable of something more. Perhaps the market is small, but it is hardly as if he’s in need of whatever money a New Zealand political autobiography might make. Sadly perhaps it reveals him finally as not much more than a political operator, without very much substance at all.

When I wrote here a few years ago about Michael Cullen’s book – which for all its faults, written against the clock of terminal illness, was better than this – I concluded this way (reacting to a quote from Helen Clark lauding Cullen)

Meanwhile Cullen – and Clark herself of course – bequeathed to the next government (who in turn bequeathed it to this one), the twin economic failures: house prices and productivity (the latter shorthand for all the opportunities foregone, especially for those nearer the bottom of the income distribution).

In that sense, what marks him out from a generation or two of New Zealand politicians, who have spent careers in office, and presided over the continuing decline?

And now the same failures were bequeathed by Robertson (and his bosses) to Willis (and hers). And just this morning we hear the latest Prime Minister distancing himself from his housing minister’s ambition for lower house prices (suggesting he just wants a slower rate of increase), and nothing at all shows any sign of improving productivity.

New Zealand politics for you…….