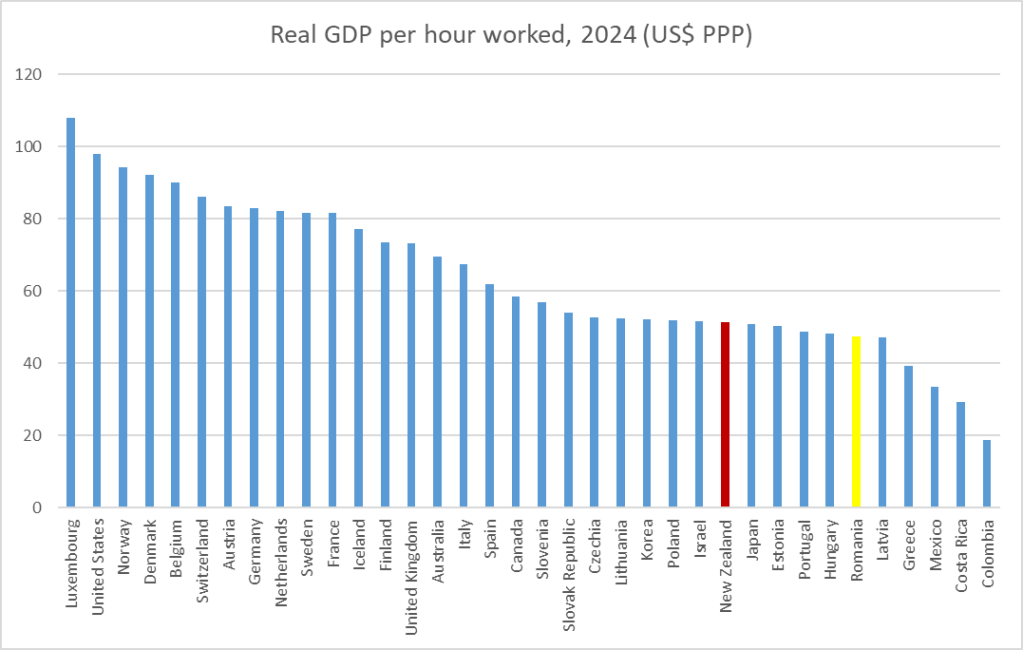

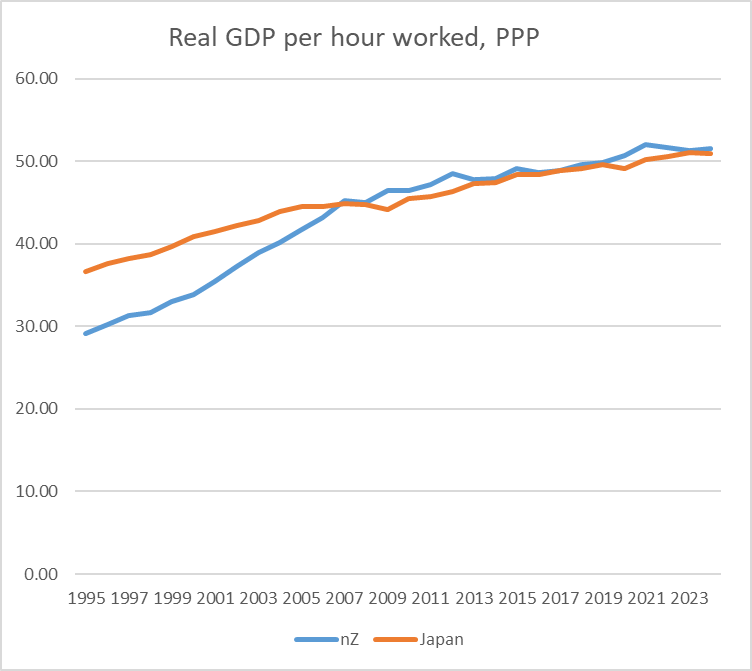

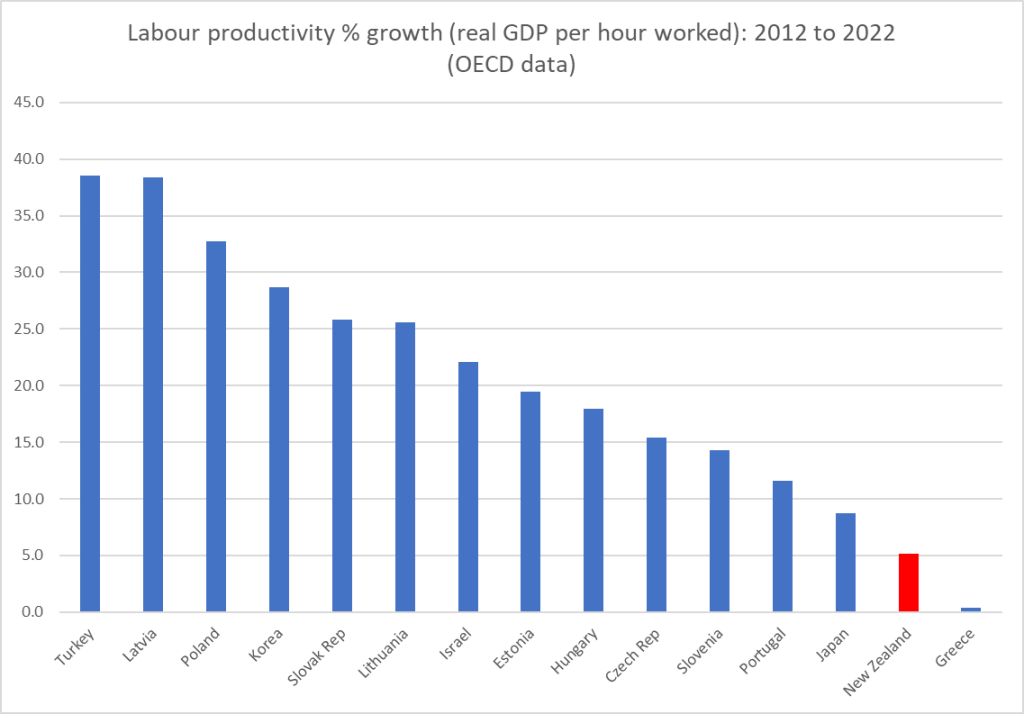

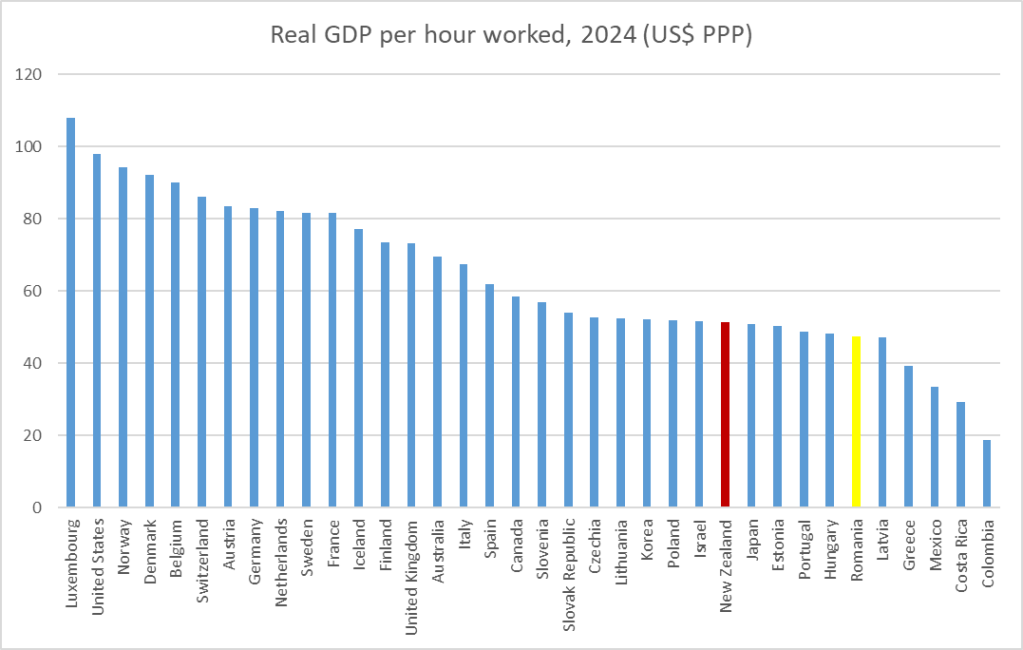

In a post last week I included this chart of the latest annual OECD data on labour productivity, expressed in PPP terms.

It was grim, in a familiar sort of way. New Zealand’s overall economic performance has long been poor (the halcyon days when New Zealand was in the top 3 in the world relegated to the history books, and stories the older among us might have heard from grandparents etc). These days more and more of the formerly communist central and eastern European countries are passing us (Romania – highlighted – will probably do so in the next five years or so).

But it reminded me of the Prime Minister’s State of the Nation speech back in January, which was full of fine rhetoric about the need to do (much) better. He told us that “2025 will bring a relentless focus on unleashing the growth we need to lift incomes, strengthen local businesses and create opportunity”.

At the time, I welcomed the rhetoric but rather doubted that the substance would come anywhere near matching it, pointing out that although in its first year the government had made some useful reforms (with productivity in view), in other areas they had taken things backwards. And they’d made no progress at all on fiscal consolidation which, while not in itself critical to productivity prospects, was not a great signal. Together with Don Brash (who’d chaired the 2025 Taskforce 15 years previously, when an earlier government’s rhetoric had briefly talked up closing those income and productivity gaps) I wrote an op-ed for the Sunday Star Times (full text in the previous link), lamenting the decades of aspirational cheap talk on the one hand and lack of realised progress (productivity gaps as large as ever or widening further) and ending this way.

We can choose to continue to drift, with just incremental reforms, as successive governments have done for 30 years even amid the fine talk. But if we do, more and more New Zealanders are likely to conclude rationally that there are better opportunities abroad, and for those who stay aspirations to first world living standards and public services will increasingly become a pipe dream.

It is a multi-decade challenge under successive future governments, but as the old line has it the longest journey start with the first step. We hope the Prime Minister’s bold rhetoric signals the beginning of a willingness to lay things on the line, to lead the debate on serious options, to spend political capital, for the serious prospect of a much better tomorrow for our children and grandchildren.

Where do things stand almost a year on? In cyclical terms, there isn’t much to show for the year. GDP growth has been on average weak (I’m assuming next week’s September quarter number comes out respectably), the unemployment rate has crept up a bit, business investment has been weak, and so on. But, for all the rhetoric and cheap attempts to either claim credit or cast blame, governments usually have little influence over short-term real economic developments, the more so in this era of operationally independent central banks. In our case, the weak economy mostly seems to have been the lagged effect of belated Reserve Bank actions to get inflation back under control, the Bank itself having previously misjudged (in tough circumstances) and let it get away on them. That, of course, doesn’t stop ludicrous government claims that falling interest rates have resulted from government actions and choices, or equally ludicrous suggestions from the left that somehow slash and burn fiscal policy accounted for the recent economic weakness. In short, there has been no fiscal consolidation. Don’t take it from me: I just use Treasury data and charts and the Secretary to the Treasury made exactly my point to FEC last week.

This year’s Budget was also (slightly) expansionary, increasing the structural fiscal deficit.

I noticed the other day a post from Don Brash in which he attempted an assessment of the government’s overall performance at the end of their second year. Don was interested in a wide range of areas, but it was the economic bits that interested me. (While noting the failure on fiscal policy) he scored the government reasonably well here.

Count me rather more sceptical. Overall, it looks to have been another year of a few useful reforms, some (modest) backward steps, and a much greater focus on attempting to gee up sentiment and activity (or appear to do so) before next October than any real drive to markedly lift New Zealand’s productivity prospects and performance over the coming decade (and thus, to the extent that good things are happening in schools, any overall economic gains are almost by necessity a decade or more away).

I’m a strong believer in much (and sustainably) lower real house prices (not just achieved by people consuming less house, less land) but, as Don notes, the Prime Minister isn’t. He claims to be keen on prices just rising less rapidly than they once used to. And although house prices have generally been falling in the last couple of years it still isn’t clear how much of that is more or less cyclical (unwinding the extraordinary 2020/21 surge) and how much might be structural. Productivity performance was pretty woeful a decade ago and real house prices now are no lower than they were then. Some economists believe that much lower house prices would themselves help materially lift productivity: I’m sceptical about that in our specific circumstances, and reckon improved housing affordability and responsiveness is mainly good (very good, if taken far enough) for its own sake. Young families on moderate incomes should be able to afford a basic house in our cities. It was so before and can be so again.

The government is tomorrow launching to great fanfare (huge lockup and all) its RMA reforms – one of the items the PM promised for this year back in January. We’ll see what that package looks like. In principle, reforms should be supportive of productivity growth. My story of New Zealand’s failure emphasises the apparently limited number of profitable opportunities here open to business (local or foreign) and if costly roadblocks can be removed the expected returns to opportunities will improve. More investment should follow.

But….it is a long road ahead. Whatever is announced tomorrow is not guaranteed to be what passes Parliament in (presumably) the dying days before the election next year. If there is a change of government (coin toss territory at present?), how likely is this particular package to endure? And, as we saw with the original RMA itself, what was initially seen as liberalising and enabling legislation turned into anything but, between the courts and successive lots of central and local government.

As for the government itself, we learned this year that the Minister of Finance had gone along with bizarre new Treasury schemes under which investment and regulatory proposals being evaluated by government agencies will use discount rates that are absurdly low and bear not the slightest relationship to the cost of capital. In the private sector, the government’s flagship policy in this year’s budget wasn’t about addressing the high tax rates on business income here but on subsidising firms to buy new capital equipment, with the biggest effective subsidy going to the sector (commercial buildings) they’d imposed a new distorting tax impost on only last year. So much for the efficient allocation of scarce resources, whether in the public or private sectors. Nor has there been any sign of top-notch appointments to any of the key economic agencies in the public sector – in the MBIE case, still no chief executive appointment at all. Small as such a reform might be, in an age of Trumpian tariffs the government hasn’t even gotten round to removing the remaining tariffs New Zealand has in place (including protection for the local ambulance building industry…of all things).

Looking back over the year it is a lot easier to be persuaded that what is driving the government – perhaps the Prime Minister in particular, and his “Minister for Economic Growth” is initiatives to grab a headline for a news cycle or two, with a focus mostly on next year’s election. We’ve had new film subsidies, new gaming subsidies, the taxpayer has been helping to buy a rugby league game for Auckland, and we’ve had the (laughable if it weren’t so bad) money thrown at the Michelin company to get their guide to cover New Zealand restaurants. Whatever you think of National’s new Kiwisaver policy, it isn’t going to shift the dial on productivity (where access to capital has never been the presenting issue, even if Kiwisaver changes ended up shifting national savings rates, itself questionable – to put it mildly). Headlines, and associated chirpy social media posts, seem to be where it is at, rather than a serious sustained reform effort, grounded in hardnosed analysis and New Zealand specific insights on just what has gone wrong here. What has seen us drift behind so many other countries.

It is one of those areas where I’d love for my pessimism to be wrong. There is a risk that after decades of failure it becomes too easy to be cynical about the latest efforts. But at this point, and two years into the government’s term, there is still little or no sign of things that are really set to turn out performance around. Inevitably a post like this has to be somewhat selective, but you could also look to the financial markets. Is there any sign, for example, of our stock market outperforming as investors markedly re-rate longer-term business (and profitability) prospects here? Not that I can see. And although our bond yields have been quite high by international standards for a long time – which is something one might also see if investment prospects were improving sharply – if anything those differentials are narrower now than they used to be.

The Prime Minister ended his January speech this way

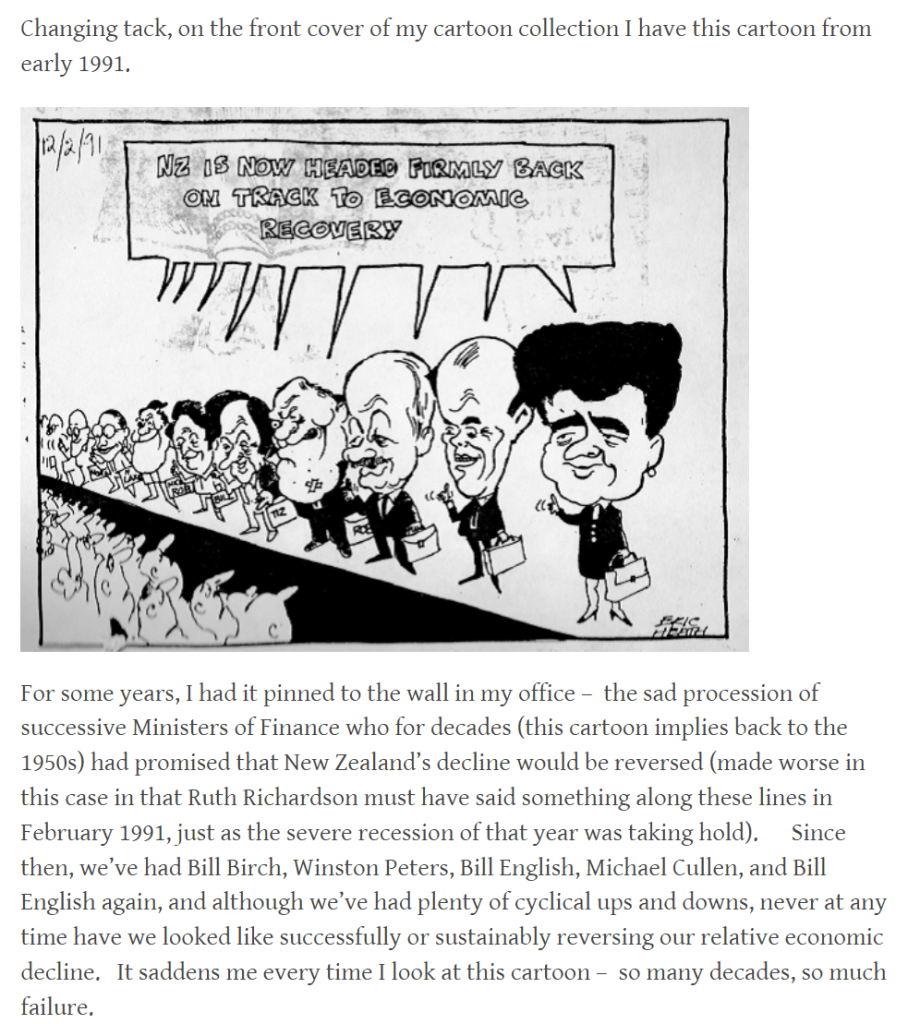

But I’m afraid he and his Minister of Finance look as if they will slot in nicely with the sequence this old cartoon (which I first ran here almost a decade ago. Yes, there will be (may already be) a cyclical upturn, but the structural failings still lie largely unaddressed (and certainly unresolved).