Or so Vernon Small, the Dominion-Post’s political columnist would have us believe. His article appeared yesterday under the heading “Reserve Bank rules need major rethink”, and then online as “Monetary policy is bust, so why are we still banking on it”.

I reckon he has rather overstated his case. “Reserve Bank ‘rules’ need following” might be a more accurate assessment.

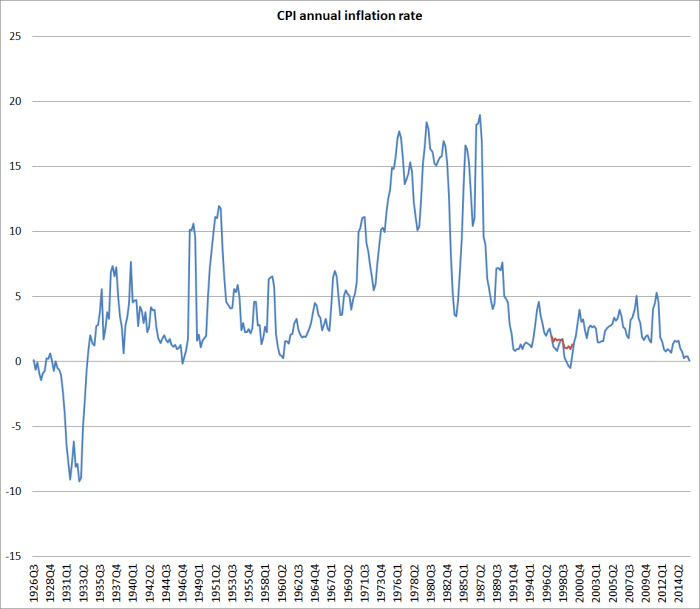

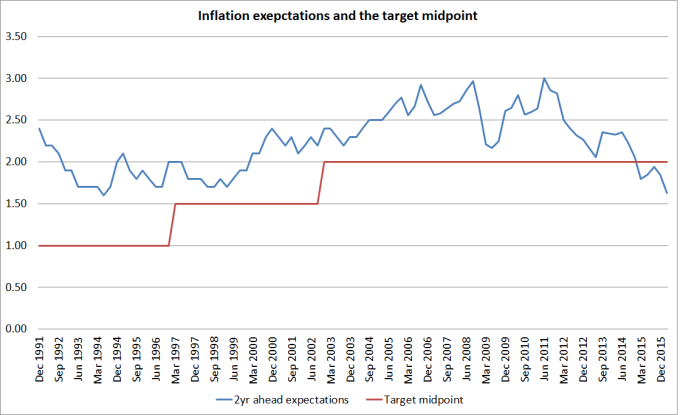

Start with the odd line that Small got from the Minister of Finance, claiming that “no one ever thought it [the inflation targeting framework] would be used to try to lift inflation”. I’m not sure where the Minister got that idea from, but as a reminder New Zealand is the classical case where it has been used, successfully, that way. In 1996, the National-New Zealand First government raised the target midpoint from 1 per cent to 1.5 per cent. And in 2002 the Labour government raised the target midpoint to 2 per cent (the then Prime Minister wanted to raise it further, to match Australia, and to Alan Bollard’s credit he resisted). As I’ve noted previously, right through to the2008/09 recession the Reserve Bank delivered inflation rates averaging higher than the successive (and increased) target midpoints.

Small does have some nice lines that had me nodding in approval

….Governor Graeme Wheeler’s rejection of a “mechanistic” approach that would see low inflation immediately trigger a cut to interest rate, currently at 2.5 per cent. It is hard to find any sophisticated analysts in the area who has made such a “mechanistic” call, but hey! Straw men have no say over what goes into their stuffing.

But he can’t quite seem to make up his mind whether, as he says, “the prime tool of monetary policy, cuts to the official cash rate, cannot achieve the target”. [my emphasis added] or whether it is more a matter that “the Reserve Bank appears reluctant to try”.

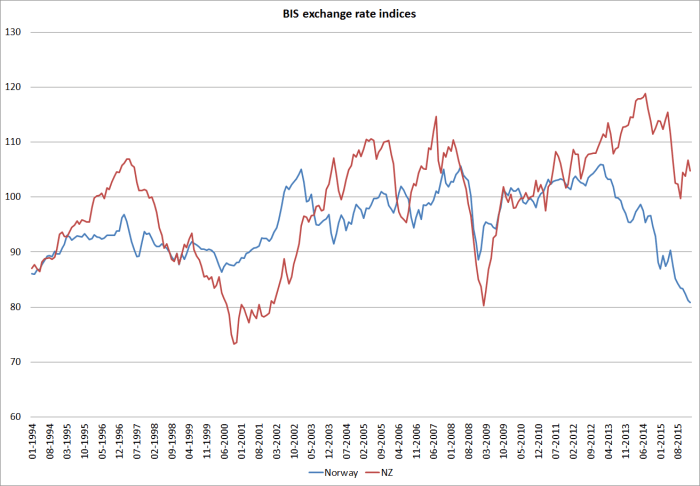

No one has advanced any evidence that, or even a strong argument why, New Zealand’s inflation rate could not have been raised, or could not now be raised. And I’m quite sure the Reserve Bank doesn’t believe such a story. In my post the other day, I set out a list of factors that suggested that keeping inflation up around target should be less hard here than in most advanced countries. And we know, for example, that another small advanced commodity exporter, Norway, has managed.

In a New Zealand context, no one seriously doubts that – all else equal – if the Reserve Bank were to come out with significant OCR cuts and a convincing statement of their determination to do whatever it takes to get and keep inflation near 2 per cent, that the exchange rate would fall. Prices of tradables would rise to some extent, and returns to tradables production in New Zealand would also rise. That combination of factors would lift the inflation rate – and, over time, the latter would be the more important channel.

New Zealand isn’t a surplus country – so we don’t find capital flooding home to our safe haven when international fears rise. We are a small remote net-borrowing country, whose currency foreigners mostly hold because of the yield advantages it typically offers. All else equal, when those yield advantages narrow or disappear so does a lot of the interest in holding New Zealand dollar assets. Stories about what, on occasion, may have happened to exchange rates in Japan or Switzerland or the United States just aren’t particularly relevant here.

For a long time, I don’t even think it was a case of the Reserve Bank being “reluctant to try” to get inflation back to target. At least while I was still closely involved there was a quite genuine and quite widely-shared belief in the Bank that there would be sufficiently strong economic growth that the inflation rate would soon lift back to around 2 per cent, and would have gone beyond that midpoint if interest rates were not raised. They were persistently wrong – and, over time, that should involve some effective accountability for the relevant decisionmakers and advisers – but it was a quite genuine belief.

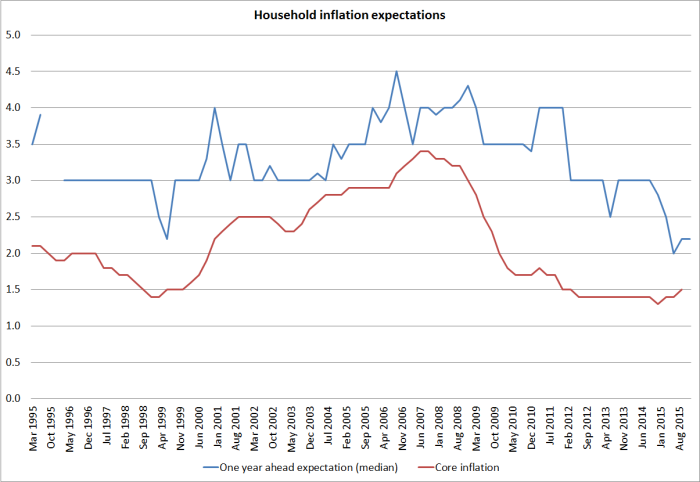

But over the last 18 months, it increasingly seems as though “reluctant to try” has been a more apt description of the Bank’s approach. This has been exemplified in some of the rather shaky arguments they have begun to run. Last year, for example, we were repeatedly told that headline inflation would rise because the exchange rate had fallen, but there was hardly any emphasis on the underlying or core inflation trends that they should have been focusing on. More recently, we’ve had a convenient fixation on a single measure of core inflation, which just happens to be the highest around, when previously they had told us what most other central banks say – there is no one ideal measure, and one needs the information from a range of series to interpret what is going on. Oh, and claims that it is “all about oil” when the data clearly don’t reflect that. And attacking straw men – claiming that those who advocate further OCR cuts are just inappropriately focused on headline inflation.

I don’t even think it is a case of the Bank looking for inflation under ever stone. Rather strangely, they have changed their view on the short-term demand effects of immigration – in a way that supports the dovish side of the story – and yet even though it was a major feature of the last MPS they can’t, or won’t, tell us why or show us their research or analysis in support of their story.

Perhaps the 2.5 per cent “barrier” has been a factor. The OCR has never been taken lower than 2.5 per cent, and there might be a psychological/mental barrier for the Governor and his advisers to taking it lower. If so, it shouldn’t be. Prior to 2008 the OCR had never been lower than 4.5 per cent, but Alan Bollard rightly blasted through that floor, lowering the OCR to 2.5 per cent in late April 2009 (by when the worst of the financial crisis itself had passed). There were debates in the Bank at the time as to whether it would be safe to go any lower – at Treasury at the time we found that rather frustrating – but that was seven years ago. Since then not only have we seen many countries with official interest rates near zero for long periods, but an increasing number tentatively experimenting with negative rates. Historical reference points are an obstacle to good policy at present, rather than being a useful anchor. If anything, they make people doubt that central banks will do enough, soon enough. In the end I’m sure the Bank will cut further, but once again they’ll have been behind the game, when they could have got ahead of it and helped recreate a climate in which people believe that, whatever was going on abroad, inflation would average around 2 per cent in New Zealand.

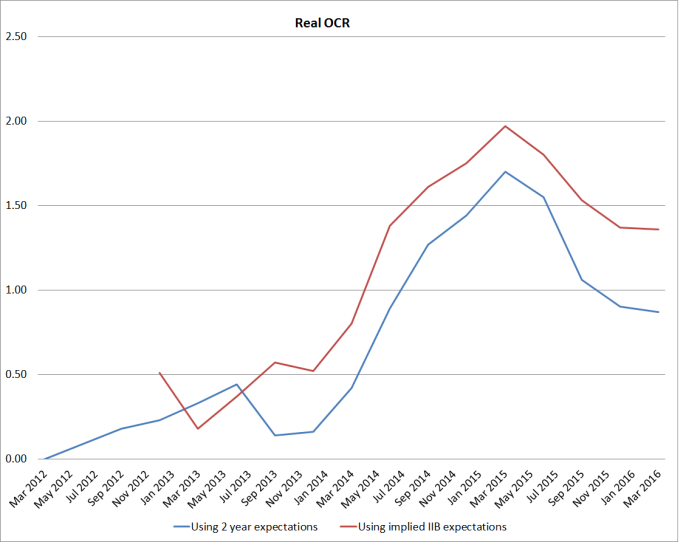

Were they reluctant to try? Well, probably latterly. Certainly the evidence is that they haven’t tried. There has been a lot of focus on last year’s OCR cuts, but recall that they only reversed the previous year’s unnecessary increases. Here is a chart of the real (inflation adjusted) OCR.

I’ve shown two versions. One, which I prefer, deflating the OCR by the two year ahead inflation expectations from the Bank’s survey, and the second using the implied long-term expectations from the indexed bond market. Whichever measures one uses, real interest rates have been rising not falling in New Zealand over the last few years. In a climate of such persistently low inflation, that shouldn’t have happened.

I’ve shown two versions. One, which I prefer, deflating the OCR by the two year ahead inflation expectations from the Bank’s survey, and the second using the implied long-term expectations from the indexed bond market. Whichever measures one uses, real interest rates have been rising not falling in New Zealand over the last few years. In a climate of such persistently low inflation, that shouldn’t have happened.

It all adds up to a story of a central bank that has been poorly led and managed, and which has not managed monetary policy well. It hasn’t been held to account well either.

But that doesn’t say the “rules” are wrong, it simply says they haven’t been followed well. Perhaps we should try operating within the “rules” rather than rush to conclude that there is something wrong with the system itself. There is no sign that delivering inflation near 2 per cent is impossible, or that it is undesirable, or that doing so would lead to otherwise weird outcomes. Protracted debates now about whether the framework is right is a distraction from the real, immediate, and easily remediable issues: even under the current framework, monetary policy has been, and is, simply too tight.

None of which is to say that we should not from time to time review the rules under which the Reserve Bank works. I’ve been championing far-reaching governance reforms, to bring the Bank more into line with international best practice, and the way other government agencies in New Zealand are run. And the Policy Targets Agreement itself expires with the Governor’s term in September next year (which creates timing problems I’ve noted earlier). I’ve argued here previously that it would be a good idea to follow the lead of Canada, and announce now a joint (and open) work programme, involving the Reserve Bank and Treasury, and outside researchers and commentators, to review the issues around the best design and contents of the PTA. The last PTA, and those before it, were done largely in secret – even though the PTA is the main document governing short-term macroeconomic management in New Zealand – and even now, three years on, the Bank refuses to release any material background papers relevant to that PTA.

We should advance work on both fronts – governance reform, and open review of the PTA issues in advance of the next renegotiation. I’m not convinced of the case for material change in the PTA – or that eg nominal GDP targeting, or wage targeting, or adding an external balance consideration – would make much practical difference anyway (points I’ve covered in earlier posts). But the research should be done, and debated, openly, to test and explore the arguments and alternatives.

But the problem at present is not that inflation targeting is being followed too closely, let alone “mechanistically”, or that it is proving overly and inappropriately restrictive. It is that isn’t being taken seriously by those – the Bank – with a legal responsibility to do so.

Using data on the general government sector’s net debt, New Zealand’s position wasn’t quite as strong. But in 2007, we were one of the 12 countries where the government sector has less debt than financial assets, still one of the stronger positions among OECD countries.

Using data on the general government sector’s net debt, New Zealand’s position wasn’t quite as strong. But in 2007, we were one of the 12 countries where the government sector has less debt than financial assets, still one of the stronger positions among OECD countries.

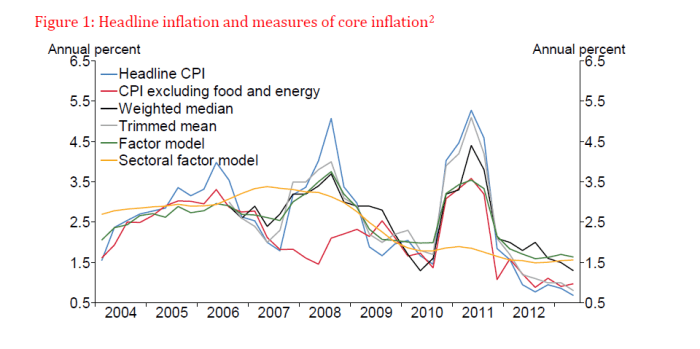

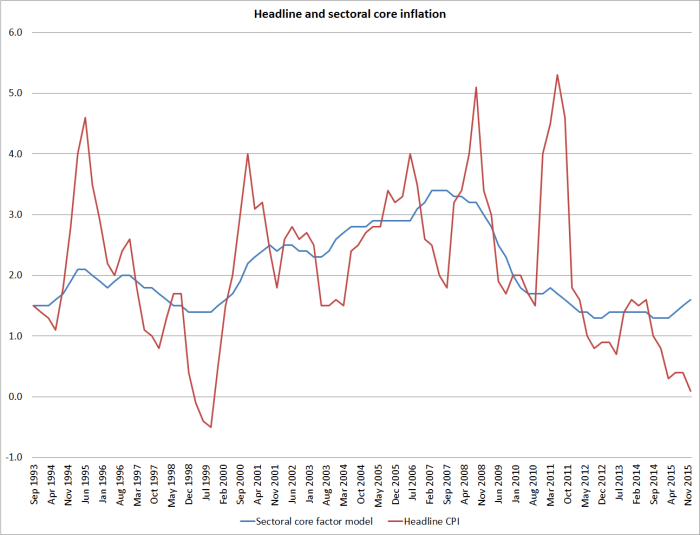

And, as with all of these sorts of models, the problems are particularly acute for the most recent observations. The model is, in effect, trying to discern the common trends in the various component price series, but it can do that increasingly reliably with the benefit of more time and more data. That makes tools like this most valuable for identifying the underlying inflation processes in periods of history (eg looking back now on the pre 2008 boom) and relatively less useful for “spot” reads on what is happening right now. In that sense, it is a little like filter-based estimates of the output gap, and it is similarly unwise to put too much weight on real-time estimates of any one model of the output gap.

And, as with all of these sorts of models, the problems are particularly acute for the most recent observations. The model is, in effect, trying to discern the common trends in the various component price series, but it can do that increasingly reliably with the benefit of more time and more data. That makes tools like this most valuable for identifying the underlying inflation processes in periods of history (eg looking back now on the pre 2008 boom) and relatively less useful for “spot” reads on what is happening right now. In that sense, it is a little like filter-based estimates of the output gap, and it is similarly unwise to put too much weight on real-time estimates of any one model of the output gap.