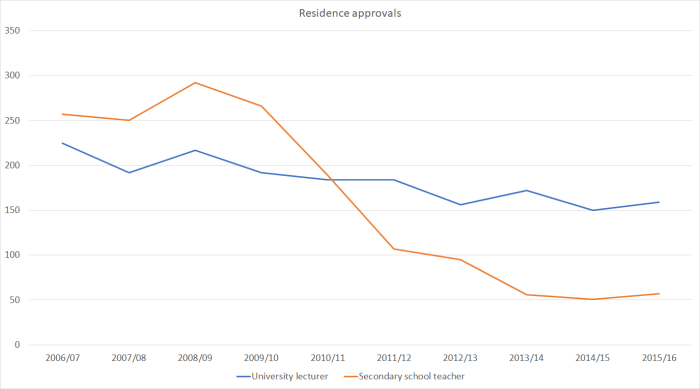

For decades – in fact going back to the 19th century – business groups in New Zealand have claimed that we need lots of immigration (often even more immigration) to relieve pressing skill shortages. No one ever seems to ask them how other countries – which typically have nowhere near as much immigration as we do – manage to survive and prosper, but set that to one side for now.

Sometimes the alleged skill shortages relate to really highly-skilled positions. I don’t suppose anyone is going to have a problem if DHBs manage to recruit the odd paediatric oncologist from abroad. But more commonly the calls relate to the sorts of jobs that require considerably less advanced skills. In generations past the call was for more domestic servants – colonial girls were apparently reluctant to take on such roles, at least at the sorts of wages that middle New Zealand wanted to offer. These days…….well, we all know the sorts of role firms claim they simply have to have immigrants for. Without them, the more florid suggest, the economy will topple over.

For an individual employer, those calls make a lot of sense. Each firm has to operate with the rest of the economy as it is. Faced with two potential employees of exactly the same quality, of course an employer will prefer the one who will work for less. And they’ll be keen to have the competition among potential employees, to keep down any pressure for higher wages. And if your firm couldn’t hire immigrants while your competitor could, your business might well be in some considerable strife. Moreover, if the whole pattern of the economy has adjusted to using large amounts of modestly-skilled immigrant labour, so that some sectors rely mainly on that labour, of course it will look to employers in those sectors as if the continuation of current policy is absolutely vital. Who, we are asked, will staff the rest homes otherwise? Or milk the cows?

Deprive an individual employer of the ability to hire modestly-skilled migrant labour, and the argument will stack up. But if we are thinking about immigration policy as a whole we need to take a macroeconomic, whole of economy, perspective. And then the perspective, or experience, of an individual employer is largely irrelevant. With a materially different immigration policy, much about the economy will be different, not just the ability of that individual firm to hire a particular immigrant.

This isn’t some striking new perspective. New Zealand economists were saying it decades ago, responding to exactly the same sort of business sector claims. Mostly the response consisted of pointing out two things, both of which really should be obvious but seem to repeatedly get lost in the “our business needs more migrants” rhetoric:

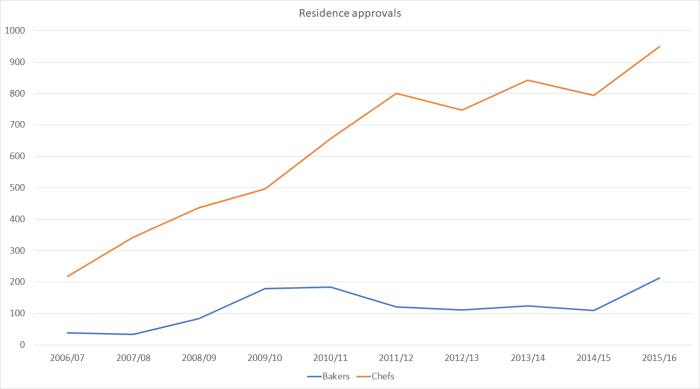

- migrants aren’t just producers (sources of labour supply) but consumers, and someone else has to produce the stuff they want to consume, and

- in a modern economy each new person generates a need for quite a lot of additional capital (a place to live, roads, schools, hospitals, shops etc) and someone else has to produce and put in place that capital.

In other words, whatever beneficial impact an individual migrant may seem to have at the level of the individual firm, there is little reason to suppose that in aggregate high rates of immigration will do anything at all to ease so-called “skill shortages” or “labour constraints”. In fact, mostly the claim was rather the reverse: big migration inflows temporarily exacerbate those pressures across the economy as a whole.

I’ve written previously about Professor Horace Belshaw’s contribution to the immigration debate as long ago as 1952, as the post-war immigration wave was getting into full swing. Belshaw was, at a time, one of our leading macroeconomists. He noted

At the time when there are more vacancies than workers, it is natural to assume that immigration will relieve the labour shortage. This however, is a superficial view. The immigrants are not only producers but also consumers. To relieve the shortage of labour it would be necessary for more to be contributed to the production of consumer goods or of export commodities used to buy imported goods than the increased numbers withdraw in consumption. That is unlikely….[and] there will be some temporary net additional pressure on consumption.

and

Of much greater importance is the fact that each immigrant requires substantial additional capital investment, not in money but in real things. Houses and additional accommodation in schools and hospitals will be needed. In order to maintain existing production and services, and even more to maximize production per head, there must be more investment in manufacturing and farming, transport, hydro-electric power, municipal amenities and so on.

To anticipate a little, immigration is not likely to ease the labour shortage while it is occurring, and is more likely to increase it because although additional consumers are brought in, more labour than they provide must be diverted to creating capital if the ratio of capital to production is to be maintained.

A few years later, the Reserve Bank published an article in its Bulletin (April 1961) on “Economic Policy for New Zealand” by a visiting British academic, who noted

It is an illusion to assume that inflationary pressure and labour shortage can be relieved by increased immigration….the main immediate effect of increased immigration is to add to the shortage of capital goods. Even single men need to be housed, and they need capital equipment with which to work in industry…..Resources have to be devoted to providing this capital that could otherwise have been devoted to increasing and modernising capital equipment per man employed.

A few years later, another leading New Zealand economist, Frank (later Sir Frank) Holmes – Belshaw’s successor as McCarthy Professor of Economics at Victoria – published a series of articles on immigration for the NZIER. I could quote from him at length, but suffice to say he was convinced that in the short-term the demand effects (including for additional labour) from increased immigration outweighed, by some considerable margin, the supply effects. And here “short-term” didn’t mean a month or two. In fact, he quoted from some recent estimates by the Monetary and Economic Council – the Productivity Commission of its time – suggesting the additional excess demand would last for up to five years.

Or, a few years on, a quote from economic historian Professor Gary Hawke

Ironically, the success with which full employment was pursued until the late 1960s led to frequent claims that labour was in short supply so that more immigrants were desirable. The output of an individual industrialist might indeed have been constrained by the unavailability of labour so that more migrants would have been beneficial to the firm, especially if the costs of migration could be shifted to taxpayers generally through government subsidies. But migrants also demanded goods and services, especially if they arrived in family groups or formed households soon after arrival and so required housing and social services such as schools and health services. The economy as a whole then remained just as “short of labour” after their arrival.”

This sort of conclusion wasn’t even very controversial among economists. Whatever the possible longer-term merits of high immigration – and on that point views did differ – no serious analyst saw it as a way to relieve labour market pressures or deal with other excess demand pressures. It simply didn’t.

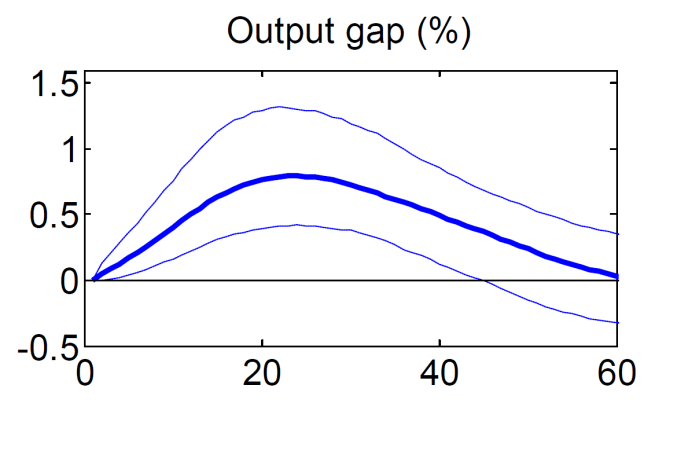

For 15 years there wasn’t very much immigration to New Zealand and in the process this knowledge seemed to have been largely lost. But the character of the economy didn’t really change, let alone the basic propositions that (a) migrants are consumers too, and (b) more people requires the accumulation of materially more physical capital. At the Reserve Bank it took us a while to wake up to this, in the face of first big post-liberalisation surge in immigration in the mid 1990s, but thereafter it became established wisdom for us. Consistent with this was a piece of research the Bank published just a few years ago. In that paper Chris McDonald looked at the impact of a one per cent lift in the population from net migration on, in this chart, the output gap (the estimated difference between actual GDP and the economy’s productive potential).

On this estimate, unexpected changes in migration increase the excess demand pressures on the New Zealand economy. The dark blue line is the central estimate, while the lighter lines represent confidence intervals around that central estimate. Coincidentally – see the Monetary and Economic Council estimates from earlier decades – on this model it takes five years (60 months) for the excess demand effects to fully dissipate. Over that time, on this model, immigration will be exacerbating aggregate labour market pressures, not relieving them.

I don’t want to put too much weight on any particular model estimates, and the Reserve Bank itself has tried to back away from this particular one. What causes the change in immigration matters to some extent. But the general conclusion – immigration does not ease resource pressures – shouldn’t be controversial. Indeed, only a few months ago some IMF modelling on New Zealand’s experience again produced similar results.

None of this should be a surprise (including to economically literate officials advising ministers). As I noted earlier there are two strands through which immigrants add to demand. The first is consumption. The household savings rate in New Zealand is roughly zero: on average, people consume what they earn. Perhaps the typical (or marginal) migrant is different – some will be sending remittances back to their homelands – but even if we assume that new immigrants have hugely different behaviour than New Zealanders, perhaps consuming equal to only 80 per cent of income, it is still a significant boost to demand. In effect, much of what the immigrants produce will be consumed by them (not exactly the same stuff, but across the economy as a whole). That is no criticism of them – people do what people do – but it is the first leg in the story about why claims that immigration eases labour shortages are typically simply false.

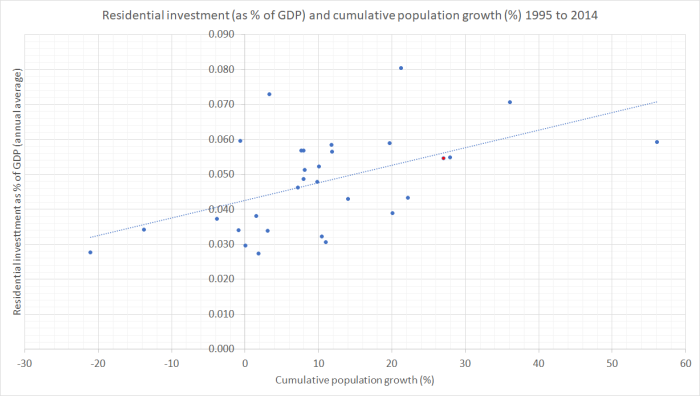

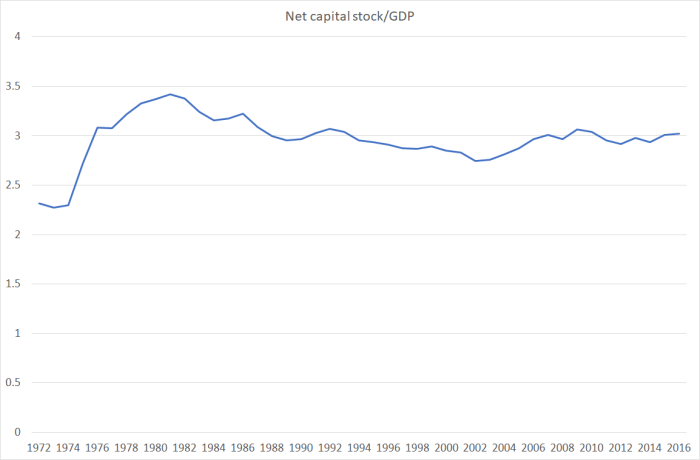

But the much more important part of the story is the capital requirements that new people (migrants or natives) generate. Here Statistics New Zealand’s capital stock data can help us. The latest estimates of the net capital stock (ie net, as in depreciated, and excluding land) are around $750 billion. Total GDP is around $250 billion. That ratio of net capital stock to GDP has been pretty stable around 3 for decades.

Each dollar of additional GDP seems to require three dollars of new capital. And this ratio understates the issue for two reasons:

- the first is that the capital stock is a net (depreciated) figure and the GDP is gross (it includes capital spending to cover depreciation – around 15 per cent of GDP), and

- the second is that our focus is here on the contribution of labour. The ratio of the net capital stock to compensation of employees (the national accounts measure of total labour earnings) is almost 7.

These are average numbers of course, and in discussing immigration the focus should be on the margin. It might be reasonable to point out that the typical migrant won’t need much more government capital in the short-term (eg schools and hospitals) – but then central government makes up only around a sixth of the total capital stock. Perhaps the typical migrant, at least their early years, will settle for less good quality housing than the typical native? But on the other hand, the productivity of the typical migrant is also likely to be lower than the national average, again at least in the early years (MBIE’s own labour market research highlights how long it takes many migrants to reach the earnings of similarly qualified locals). So I’m not here to give you a definitive number for how much new capital spending is typically going to be associated with each new migrant, but it will be large. It will be a significant multiple of the first year’s labour supply of the typical new migrant. It will, in other words, for several years exacerbate any aggregate shortages of labour, not relieve them.

Of course, quite a bit of physical capital is imported. All those earlier estimates already, explicitly or implicitly, take those imports into account. SNZ’s input-output tables suggest that across capital formation as a whole the import component isn’t high – around 21 per cent in 2013. That shouldn’t be surprising. Buildings make more than half the physical capital stock, and although they have some imported components, there is a great deal of domestic labour (and domestically produced timber and concrete). Accommodating more people simply adds greatly to the demand for employment over the first few years after they arrive.

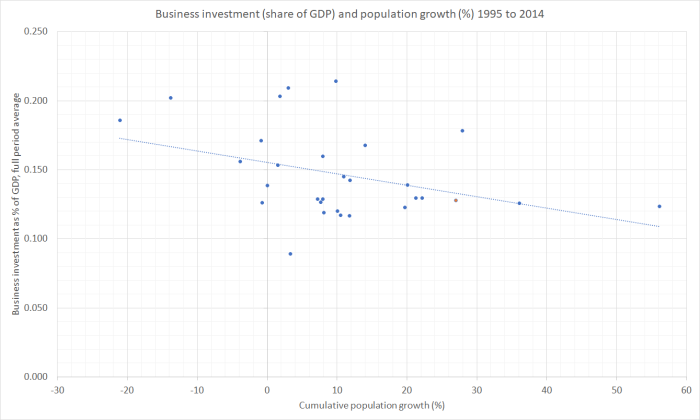

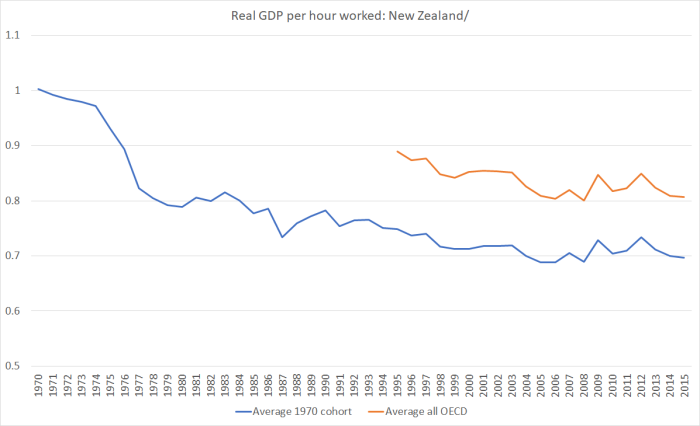

Commentators and politicians who argue that migrants don’t take jobs away from New Zealanders are largely correct (again, past modelling exercises confirm that sort of intuition). They don’t do so – and they don’t succeed in lowering aggregate wages – precisely because influxes of immigration (or unexpected reductions in the net outflow of New Zealanders) add to demand – for goods and services, but thus for labour – more than they add to supply. There are probably some sector-specific adverse wage effects – in sectors where immigrant labour has been made particularly readily available – but much the bigger determinant of overall real wage prospects in New Zealand is productivity growth. Sadly, our record on that score over many decades has been poor. Over the last five years it has been shocking – no labour productivity growth at all. That, in turn, may be in part because of the effects of rapid population growth – all that spending associated with more people crowding out (notably through a high exchange rate) activities that might have offered more productivity growth prospects. Despite the political rhetoric to the contrary, there is no surprise that more people create more jobs – always have, probably always will. But there is also no surprise that as it was decades ago, is now, and probably ever will be, increased immigration doesn’t ease overall labour market pressures.

So too much of the New Zealand debate is simply misplaced. If we want to deal with domestic unemployment, as we should, look to monetary policy (it was a point Frank Holmes made 50 years ago). In the current context, hire a Governor who will take seriously the ambition of non-inflationary full employment. If there are sectoral market pressures, let wages in those sectors adjust – that is what happens to tomato prices when tomatoes are in short supply. And if we were serious about wanting sustained productivity growth – as we should be – it increasingly looks as though much lower levels of non-citizen migration would be the way to go.

On our woeful productivity performance, even the Reserve Bank is starting to openly recognise the issue. This chart (using their estimate of TFP) was in the chief economist’s speech this morning

Figure 3: Potential GDP Growth

Source: RBNZ estimates.

Little investment – as the Deputy Governor noted in his speech last week – and almost no productivity growth, and simply lots and lots more people. To what end – beneficial to the average New Zealander – one might reasonably wonder?