The Prime Minister attracted considerable coverage last week for his suggestion that a tax might be applied non-resident (however defined) holdings of land. The Prime Minister wasn’t very specific about the options he had in mind, but it probably didn’t matter – it got some mostly favourable coverage on an issue (house prices, in Auckland in particular) where the government probably senses that it might be politically vulnerable.

Quite how house prices play politically has never really been clear to me. I’ve noted before that I’m not aware of a single example of a city or country that, having once put in place restrictive land use regulation, has ever substantially unwound those controls. I can well understand existing users’ unease about greater intensification, and in particular the coordination challenges that can arise. Existing owners as a whole in suburb near the central city might be (considerably) better off financially from allowing their land to be used more intensively, but that won’t necessarily be so for each of them if such development occurs piecemeal, or if benefits are captured by those first in the queue. The market seems to deal with these issues through private ex ante contracts, the covenants that are now used in most new subdivisions (and which the Productivity Commission was quite disapproving in its report last year).

And I can also understand that no one really wants the value of their property to fall much. Of course, for many it actually doesn’t matter very much. If you haven’t got a mortgage and plan to live in the same city for the rest of your life, the market price of houses in your area just isn’t (or shouldn’t be) that important to you. For those with very large recent mortgages it is another matter. For them, and especially those who aren’t owner-occupiers, falling house prices look like a visceral threat.

But then the mortgage-free are in many cases those with children, already adult or approaching adulthood, who face the huge – increasingly insurmountable – hurdles to entering the owner-occupation market. That should be quite some motivation to be concerned about policies which keep house prices very high, or keep driving them up further. Increasing the physical footprint of cities, and allowing that process to happen in ways and in places that offer the best opportunities (rather than where Council officials and politicians dictate) looks as though it should be the answer. But bureaucrats and politicians obstruct those processes, and seem to get away with it because the issues are complex, and because they cover their tracks, blaming high house (and urban land) prices on banks, the tax system, the building industry, “speculators”, “land bankers”, becoming a “global city”, or whatever.

Other bureaucrats and politicians peddle the line that high levels of non-citizen permanent immigration are somehow good for us. High house prices are just one of those things – a price of progress, indeed of success, so the Prime Minister would often have us believe.

Once in place, distortionary policies, even very costly ones, often last for a long time. We saw that in New Zealand with the import licensing regime first put in place in the 1930s, which wasn’t finally abolished until 1992. It was an enormously inefficient system, driving up costs on many items (and restricting choice) for most people, it was contested politically (largely unwound in the early 1950s, and then re-imposed by the next government). But the entrenched interests of those who benefited from the system (or thought they did) combined with ideologies of “national development” to make it very difficult to undo. Licence-holders themselves obviously benefited, but many of the employees of firms producing products protected by the licensing regime thought they did too. And transitions are/were costly – we saw a lot of that in the 1980s, when big steps were finally made in dismantling the regime. A larger proportion of the population is employed now than was then, but that didn’t mean the transition wasn’t difficult, and even traumatic, for many individuals, and even for whole towns.

One might have hoped that the rigged housing market was different, but it doesn’t seem to be. The distributional effects (winners and losers) are far larger than any aggregate adverse effects (I’m skeptical that GDP is much smaller than otherwise because the housing market is so badly distorted). And unfortunately, those most adversely affected tend to be the poorer, younger, less sophisticated elements in society – those on the peripheries. One might have hoped that one or other main party would have made grappling with these issues a real priority, consistent with the underlying values they claim to represent: National perhaps on some ‘property-owning democracy’ line, in which communities will be stronger etc when property ownership is more broadly based, providing a “fair go” to the hardworking and aspiring classes. Or Labour, built on a fight for the rights and interests of ordinary workers, campaigning for the full inclusion and equal opportunities for peripheral groups.

But it simply doesn’t happen. Instead, the Prime Minister keeps talking of high house prices as “a good thing”, and a sign of success. And for all the somewhat encouraging talk from Labour’s Phil Twyford, less than 18 months out from an election, there is little public sense of a party making fixing the housing market a defining issue. Time will tell. Rigged markets are hard to unscramble – politically hard, not technically so. Doing something far-reaching could be very costly for groups who would quickly become quite vocal, and loss aversion is a powerful force.

Where do land taxes fit within all this? I outlined some of my skepticism about a general land tax in a post late last year. But the Prime Minister’s latest comments relate only to non-resident purchasers. The theoretical arguments for a general land tax don’t apply to one explicitly targeted at a specific subgroup. Instead a land tax appears to be one of the few possible tools (specific to foreign purchasers) left to the government – having signed up to a succession of preferential trade (and other) agreements – if, as the Prime Minister put it, it could be shown that non-resident purchasers were a big influence on the housing market. Of course, we haven’t yet seen the data the government has started collecting, but even when we do there will no doubt be lots of debate about what it means. Say that it shows that 1 per cent of purchases in the last six months have been from non-resident foreigners. One per cent doesn’t sound much. But the significance depends on a various things, including a variety of elasticities. If the supply of houses and urban land was totally fixed (it isn’t, but this is just an illustrative example), a one per cent boost to demand could have a considerable impact on the price of houses. If New Zealand residents were deterred from buying by even the slightest increase in price, then an increase in non-resident foreign demand might have very little impact on price even if supply was largely fixed. Various quantitative researchers will have various estimates of these different elasticities. But some past work has suggested that a 1 per cent increase in population, say, can have a material impact on house prices.

I had a couple of posts on the non-resident purchases issues last year. Despite my general stance strongly favouring a pretty liberal regime for foreign investment, the housing supply market is so badly messed up that I don’t think we should rule out restrictions targeting non-resident foreign purchasers, as a second or third best option (perhaps especially if there was evidence that a large proportion of such purchases were being left empty). The capital outflows from China – which is where the main issue is – are historically unprecedented. They aren’t a normal phenomenon of an emerging economy, but a reflection of a whole variety of things that are badly wrong with the governance and rule of law in China.

But is a land tax the answer? If it is, it is a pretty unappealing one. It would seem to be a tax planners’ dream. One of the appeals of a general land tax is that the land is fixed, and some identifiable entity (person, company, trust, government) one owns each piece of land. It doesn’t really matter who owns it, but someone will have to pay the tax. A land tax focused only on some definition of non-resident purchasers means it makes a huge difference who owns the land. If I own it, there is no tax liability. If a family in Shanghai owns it there is. Which looks like a pretty clear incentive to have the land owned by New Zealanders, and (to the extent there is demand) the things on the land owned by the foreigners. No doubt lots of clever intrusive anti-avoidance provisions could be added to any land tax legislation but to quite what end? Are we better off if, say, the non-residents purchasers bought apartments (which typically have a smaller land component) rather than, say, standalone houses? Perhaps if it stimulated a supply of new apartments – for which there would be an enduring demand – but not if it largely just reallocated who owned what within an existing housing stock.

And there is, of course, the question of what might be a reasonable rate of land tax. Long-term New Zealand government bond yields in New Zealand are among the highest in the world. At present, those real bond yields are just over 2 per cent per annum. Imposing a tax of 1 per cent per annum on value of land (including farm land?) would be a very heavy burden in such a low yield environment. Perhaps it might not matter too much to those seeking to safeguard their capital (return of capital rather than return on capital), but if so it might not make that much difference to offshore demand either. I’ve seen talk of higher rates – Rodney Hide’s Herald column yesterday talked of a 3 per cent annual rate – but in such a low yield environment such tax rates could quickly starting looking like expropriation, confiscatory in intent. I suspect our preferential trade agreement partners might start looking askance at that.

For what it is worth, I think a serious response to the house and urban land price affordability issue would have several dimensions, including:

- limiting the assessability and deductibility of interest to the real (inflation-adjusted) interest only. The ability to offset losses in one activity against profits in others is a good feature of the tax system not a flaw, but there is no good economic case for taxing the inflation component of nominal interest, or allowing borrowers to deduct the inflation component. This is a small issue, especially at present when inflation is so low, but it would be good tax policy and work towards slightly better housing market outcomes.

- creating a presumptive right for owners to build, say, two storey dwellings on any land, with associated provisions to developers/purchasers to cover the costs of associated infrastructure (whether through private provision, or differential rates).

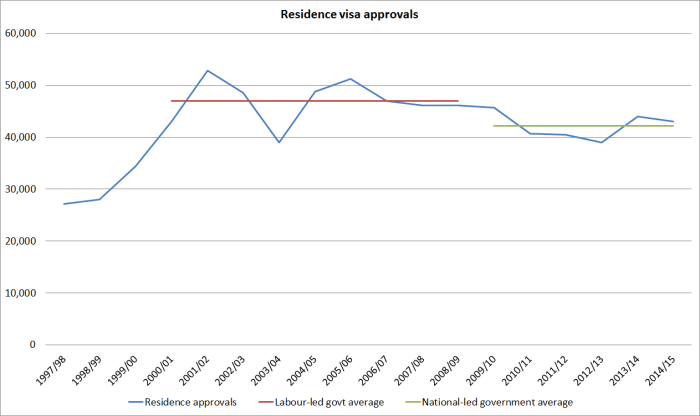

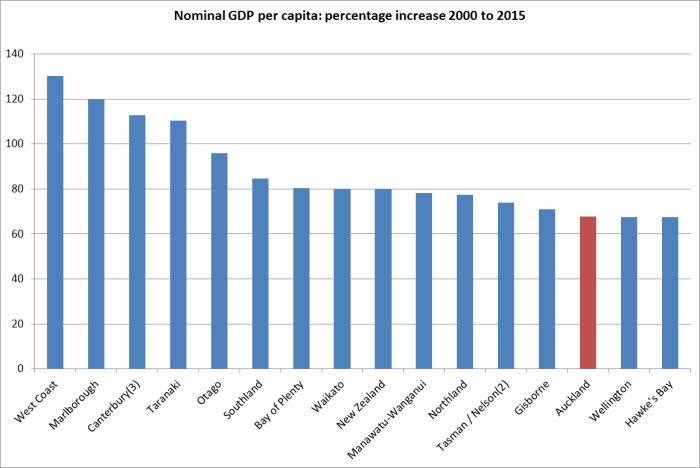

- sharply cutting the target level of residence approvals under the New Zealand immigration programme, from the current 45000 to 50000 per annum to perhaps 10000 to 15000 per annum. Since there is no evidence that New Zealanders, as a whole, have been gaining from the high trend levels of immigration – and indications that Auckland, prime recipient of the inflows, has been persistently underperforming, this would represent immigration policy reform in any case. But it would also have material implications for trend housing market pressures as well.

The third element would be the one that would be easiest to implement. But, of course, like the policies around housing supply – or import licensing (see above) – the distributional implications of the current arrangements (positive and negative) are probably larger than the overall economic effects. Those who see themselves as “winners” from the current arrangements – a funny mix , including those who genuinely benefit, and those with a “feel good” preference for diversity – are likely to be more vocal, and more easily heard, than those who pay the price of an misguided approach to economic management: a “critical economic lever” (MBIE’s words) that has done little or nothing positive for New Zealanders as a whole. The parallels with Think Big in the 1980s, or with the protective regime of the 1930s to 1980s, each well-intentioned and with their own internal logic, are sobering.