One of the great things about being a prominent organisation that releases complex material to select media under embargo is that you can get uncontested coverage in the first (and probably only) news cycle. Adrian Orr will have been glad of that when it came to the embargoed release yesterday (the public only got to see it at 5:43 this morning) of the IMF’s Article IV report, and in particular the short (600 words) annex on the fiscal implications of the Reserve Bank’s LSAP programme – the one on which the Reserve Bank has so far lost $11bn.

It was 10 days or so ago that we first heard that some such paper was coming. The Governor was being interviewed by the Herald‘s Madison Reidy after the Monetary Policy Statement. She asked Orr about the LSAP losses and noted in contrast the fiscal costs of the storms/cyclone this year. In his usual effusive style he responded that the LSAP itself had already more than paid for the cyclone recovery costs, moving on to suggest that only accountants could think otherwise “who know the cost of everything and the value of nothing”. He then went to say that the IMF had a paper, which he hoped would be published, showing that the LSAP had actually improved the government’s finances, and that it would offer the “proper story” not some “piecemeal accounting story”.

That caught my eye. Knowing that the IMF Article IV report was due before long, I wondered if they’d have a Selected Issues paper on the topic. These are supplementary research pieces, usually 15-20 pages or so, undertaken by Fund staff (often on topics requested by the authorities) as part of the Article IV review process. The latest two such papers are here.

But it proved not. Instead, we got only a little annex on the topic (600 words and two pictures) on pages 64-66 of the main report. The “proper story” it certainly isn’t – and in fairness to the Fund, as distinct from the Governor, it doesn’t really purport to be. What it is is a little exercise by a few researchers (not working specifically on New Zealand) using a model, as yet unpublished, that they have developed for work on central bank exit strategies, showing that on certain assumptions something like the LSAP could end up producing net fiscal benefits. Surprise, surprise. Of course. It could. The question really is about the realism of the assumptions etc.

Orr, and probably the Fund, will have been pretty happy with the Herald‘s coverage this morning, under the headline “Reserve Bank’s money-printing buoyed Govt books, says IMF” (well except that – rightly – the Governor and IMF would disavow the suggestion that the LSAP was “money-printing”: it was just an enormous asset swap). The results could be read as backing the Governor’s claim – a year ago in an interview with the same journalist – that the benefits to the economy had been “multiples” of the direct cost (although she seems not to have realised that because she contrasts these results with Orr’s 2022 claim).

The first of the two charts really captures the gist of why the little model analysis sheds no useful light at all (SS here simply means steady state).

I showed the top left chart to a 3rd year economics undergraduate, who immediately spotted the problem. It isn’t very hard.

You’ll note that in this example real GDP falls materially below the steady state, or potential, and stays there – converging ever so slowly – for years. By construction of the model, the LSAP intervention – about the scale of the actual LSAP programme – lifts real GDP, but again throughout the entire forecast period real output is at or below potential. There is, in other words, a negative output gap right through the period in the scenario. As the model is constructed, the LSAP intervention boosts real GDP, so that there is a smaller negative output gap. But it is always either negative or zero. Thus, the LSAP has unambiguously boosted real GDP, and thus tax revenues. Working back from the (few) numbers in the little note, and knowing the tax/GDP ratio in New Zealand is about 30 per cent, the total GDP difference must be of the order of 7-8 per cent of GDP. The current LSAP losses to the Reserve Bank are just over 2.5 per cent of GDP, so on those numbers the gains from the LSAP would be “multiples” of the Reserve Bank losses.

But have we had a negative output gap throughout the last 3+ years since the LSAP got underway at the end of March 2020?

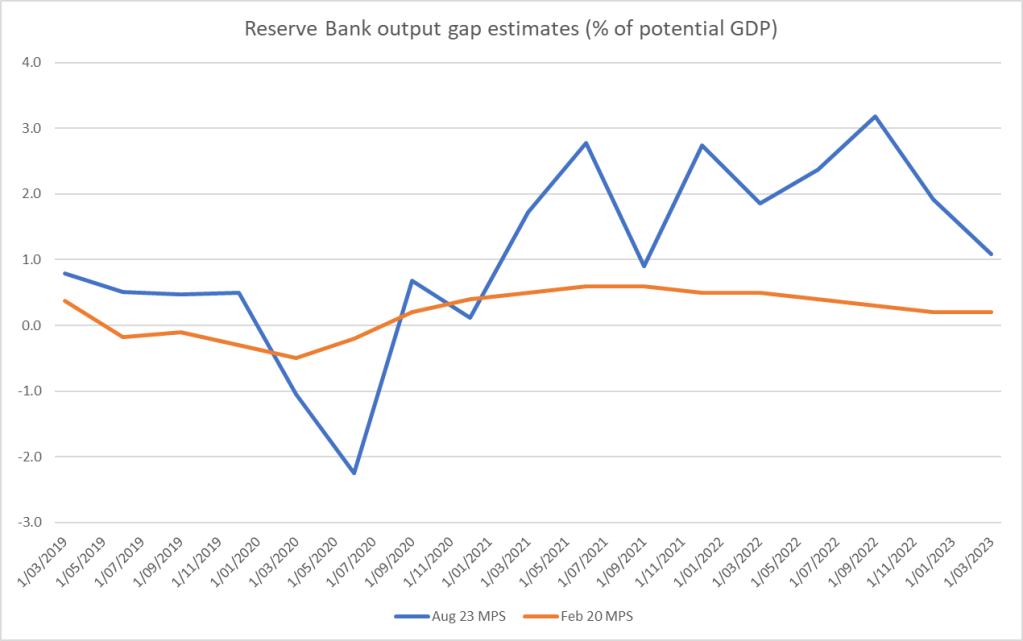

Not according to the Reserve Bank, or to any other serious macroeconomic analyst. But since it is the Reserve Bank making the bold claims, and because their numbers are easy to find, here is the Reserve Bank’s current view of the output gap over the period since the start of 2019. I’ve also shown their projections from the last (pre Covid, pre LSAP) MPS.

The output gap is now estimated – several years on – to have been negative for only two quarters, March and June 2020. Every quarter from September 2020 onwards has been positive.

Doesn’t that just mean even more tax revenue and more net benefit?

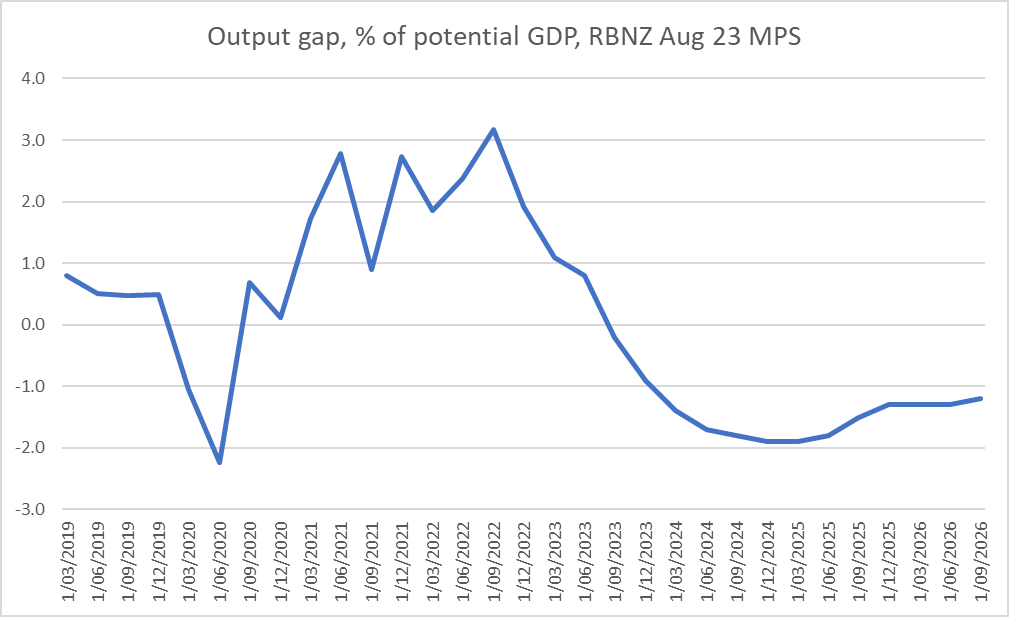

No, it doesn’t. What went with the persistently positive and large output gap? Why, that was the sharp and now sustained rise in inflation. And how do the Reserve Bank’s modelling and forecast efforts envisage that core inflation comes back to target again? Why, via (raising the OCR and engendering) a fairly protracted negative output gap

and when output is running below potential for several years (and on these projections it isn’t even back to potential by 2026), tax revenue will, all else equal, be running lower than it would otherwise have been. In fact, the way the forecasting models are set up, things are pretty much symmetrical – it will be take roughly as much excess capacity as there was excess demand. We simply haven’t been in the world the IMF’s little desk exercise assumed/portrayed. And thus the numbers are just pretty meaningless when it comes to making claims about the fiscal or other net costs/ benefits of the LSAP. In his day, the Governor would have recognised that once he read the short note and thought for a minute or two.

There are many other limitations to the analysis, even on its own terms. First, the subsequent inflation seems to be treated as quite unrelated to the (with hindsight excessive) stimulus that had gone before. Second, while they assert that the LSAP was a better (net cheaper) intervention than anything else they make no attempt to show this. Thus, had we wanted to throw another $11bn at the economy we could instead have simply given the money to households ($2000 or so per capita). That almost certainly would have engendered a significant demand response (and more than what most New Zealand economists outside Bank believe the LSAP actually did). And we know that actually the OCR hadn’t been lowered to any sort of effective floor, just to the 0.25 per cent the MPC had chosen to set it at. So at least some of any stimulus the LSAP provided could have been done simply by setting the OCR lower – at no risk to the Crown at all. The Funding for Lending programme, used long and late by the Bank, seemed to be an effective tool for stimulus…..and involved no financial risk to taxpayers at all. Had the Bank been doing its job in the run-up to Covid, the negative OCR tool would have been available from the start. You might not like that tool, but the Governor had told us before Covid that he did, and it could have been used at no financial risk to the Crown.

And all this simply assumes – no serious attempt has ever been made to show – that in the specific circumstances of New Zealand (where shorter-term rates are overwhelmingly what matter, and they were anchored by OCR expectations), the LSAP had any material (even inflationary) stimulus at all, to justify the huge financial risks that were taken with no serious advance scrutiny, and which ended up going very bad.

I could take the opportunity to run through all the arguments around LSAP effectiveness again, but I won’t. About a year ago Orr made a strong play to defend it, and the alleged benefits, and I spent a long post then unpicking his arguments. Sometimes – there are so many – one just forgets occasions when Orr has just made stuff up. He was at it again this week.

As for the IMF piece, it is what it is. If you ever find yourself in a deep economic hole, seemingly intractable, you want all the monetary policy stimulus you can get. Best of all, use the OCR and use it aggressively. Perhaps QE can add some value on occasion (probably not much in New Zealand, but perhaps anything might help then in such a scenario). But that – we now realise – just isn’t where the New Zealand economy – or most other economies – found themselves after March 2020. In fact, it is the Reserve Bank itself that now reckons the economy was already overheating – GDP above potential – by the second half of 2020.