Senior figures at the Reserve Bank have an alarming record of just making stuff up (and getting away with it). Just last week, documents showed that the Board chair had told entirely made-up stories to Treasury, apparently trying to rewrite history, in turn leading an incurious Treasury to lie to the media. And on several occasions the Governor has been found actively misleading Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee (eg here, here, and here).

He (and, sadly, his chief economist) were at it again this morning at FEC. Asked why it was taking so long for inflation to come down we got a long list of supply shocks (ie things they weren’t responsible for) and little or no acknowledgment at all that excess demand (reflected in things like the unsustainably tight labour market), the thing monetary policy influences, might have played even part of a role.

But then this conversation ensued (not word for word)

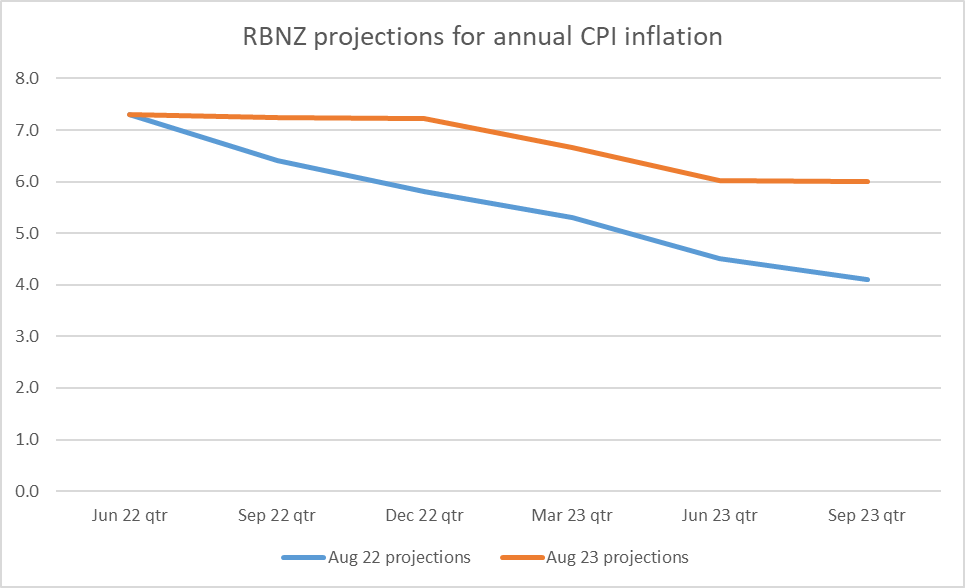

Nicola Willis: A year ago your forecasts said inflation by now [September quarter 2023] would be 4.1 per cent, and now you are picking it will be 6.0 per cent. What explains that magnitude of error?

Orr: [after some burble] supply shocks and in particular the storms and cyclone Gabrielle

Nicola Willis: How much difference did the cyclone make?

Orr: I don’t know.

[a minute or two later]

Anna Lorck (Labour backbencher): Governor, how much difference has the cyclone made to inflation?

At this point, the Bank’s forecasting manager, sitting in the back row, pipes up and is invited forward and she explains that they think the cyclone might explain 0.1 or 0.2 per cent, (the effect through fresh fruit and vegetable prices)….. [and it seems very unlikely that the Governor did not already know this, having just sat through days of MPC deliberations].

As I say, they just make stuff up. Here it is worth remembering that a) fruit and vegetable prices, and especially extreme moves in them, will be out of all/most core inflation measures, and b) that as the Bank’s own MPS yesterday noted, several times, core inflation – the bit shaped by excess demand and expectations pressures – was hanging up and had not yet shown signs of falling.

These are the RB inflation projections Willis was referring to

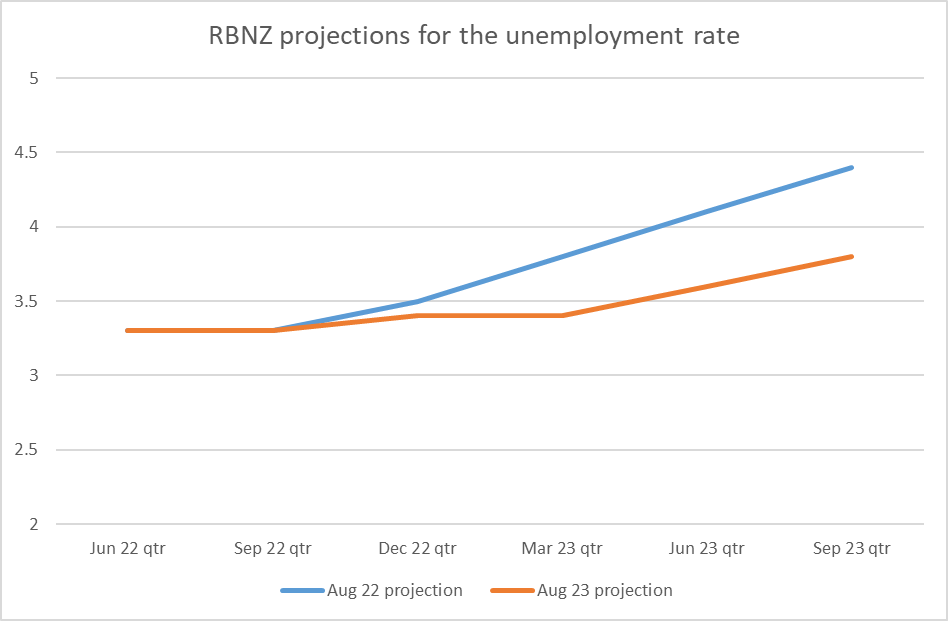

And here are their unemployment rate projections from the same two sets of forecasts

Slack simply has not re-emerged in the economy as early or to the extent the Reserve Bank expected a year ago. That isn’t about adverse supply shocks. It is just a(nother) forecasting error re excess demand from the well-paid committee (and their large supporting staff) charged with delivering annual inflation near 2 per cent.

Despite the chief economist’s claims (again, at FEC this morning) that the Bank is pretty good at forecasting, in this episode (last few years) they’ve been consistently worse than respondents to the Bank’s own expectations survey (who’ve been bad enough).

All that was just about a few minutes in the MPC hearing, where (as so often) that Bank treats parliamentary scrutiny and accountability as some sort of game where anything goes. The post was actually going to be about the MPS itself.

It was a pretty thin and disappointing document, even with the modest nudge in the direction of possible further OCR increases. I read it more slowly and carefully than I sometimes do, and came away if anything more convinced that the combination of their own persistent mistakes and their own read of the data support a higher OCR now, to be confident that we will really get inflation back to 2 per cent fairly promptly from the current still elevated core levels. And astonished that, with no supporting analysis for the claim, the MPC continues with the bold claim – not paralleled as far as I’m aware in any other advanced country central bank – that they are “confident” they have done enough. “Confident” here seems most likely to be empty bluster, with the risk that it is also intended to keep the natives quiet for the weeks remaining before the election.

I have been, and still am, hesitant about suggesting that the Governor and the MPC are operating in a deliberately partisan way. But it gets harder to believe such a pro-incumbent bias is playing no part (consciously or unconsciously) in their words and actions. I’ve documented previously the skewed, highly unconventional, and very favourable to Labour, way the Bank treated fiscal policy in May following the more expansionary Budget. In this MPS, the word “deficit” appears 44 times, but it appears that every single one of those references is to the current account deficit, and not one to the budget deficit (altho there is a single reference to “the Government’s plan to return the Budget to surplus”). The same weird framing of fiscal issues was there not only in the rest of the document but explicitly from the Governor this morning. He claimed that what mattered for the Bank from fiscal policy was only/mostly government consumption and investment spending, not taxes (or apparently transfers), let alone changes in structural deficits (the usual model). Having provided no supporting analysis or rationale whatever – speech, research paper, analytical note, just nothing – the Governor appears to have simply tossed the conventional fiscal impulse approach out the window, at just a time when doing so suits his political masters. Perhaps it is all coincidence, but either way it is troubling.

More generally, relevant supporting analysis was remarkably thin on the ground. There was no analysis at all of past reductions in inflation in New Zealand, no analysis of the forecasting mistakes of the last year (see above), no serious analysis of what has gone on in the US, Canada, or Australia where core inflation has turned down (and what, if any, comparative insights those experiences might offer). (At FEC this morning, they were asked about the US case, and it was clear they’d not even thought hard as the chief economist was reduced to lines like “it is a very different economy”, “very flexible”, and that was it…….) And there seemed to be considerably more discussion of the current account deficit – which the Bank has no direct responsibility for – than of inflation for which it does. Even with a four page special topic on the current account and a five page one on immigration it is hard to think of any useful analytical insight one comes away from the document with. And remember that this is it: there is no stream of thoughtful speeches likely to emerge from MPC members over the coming weeks elaborating on bits of research or analysis there was no space for in the MPS itself.

And, revealing the poor quality of the MPC itself, even though core inflation lingers high, miles above target, there is no sign in the minutes of any serious thoughtful alternative approaches. We are left to assume that in a highly uncertain environment all these senior public officials just went with the flow. They are “confident” we are told again, but with no hint of why, or no hint of anything like the normal degree of divergence one might reasonably expect if seven able people were debating such challenging issues at the best of times.

Even allowing for signs that things are slowing – and remember we had two negative quarters of GDP growth late last year and early this year already – there seems to be more wishful thinking and hopefulness than serious supporting analysis (and, of course, any contrition – these people wreaked this inflationary havoc and the expected rise in unemployment – is totally absent). Not even the MPC hides the fact that “domestically-generated inflation” is not only hanging up but is also “marginally higher” than they’d expected as recently as May.

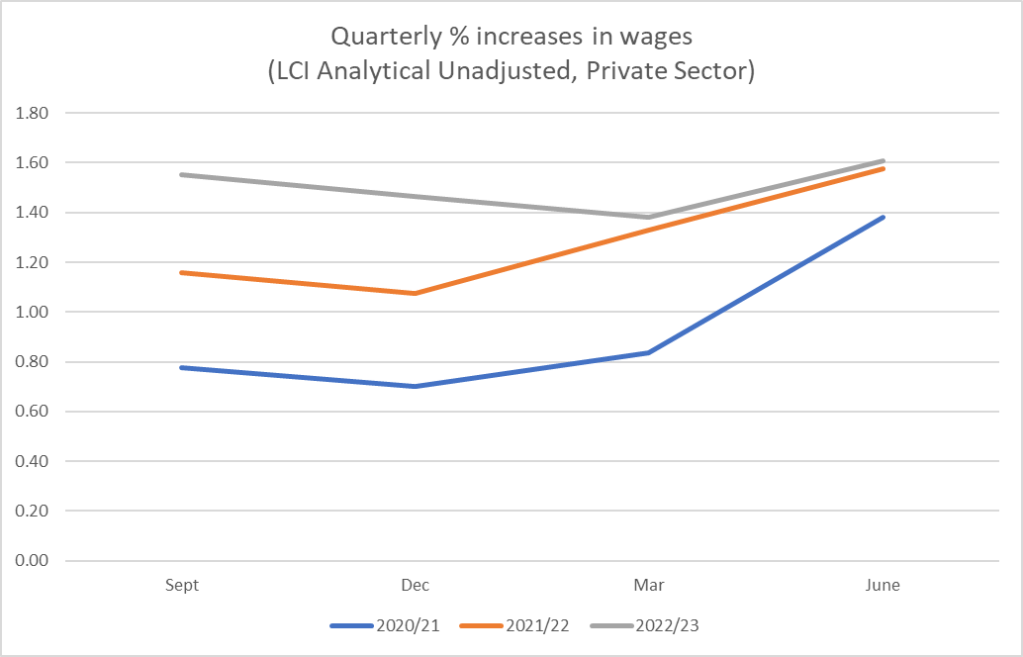

Among the straws they attempt to clutch at is a claim that “private sector wage inflation appears to have peaked and has started to ease” and “most measures of annual wage inflation have begun to ease”. But of all the series they seek to draw on, the only one that actually attempts to measure wage rates (rather than hourly or weekly earnings, or something approximating unit labour costs) is the LCI Analytical Unadjusted series. As I showed earlier in the week, at best this series seems close to peaking, but there is no sign yet of any slowdown.

Perhaps as to the point, even when some series have started slowing – and neither core inflation nor wage rates yet have – there is a long way to go to get core inflation from 6 per cent to 2 per cent, and the Bank’s forecasts and policy have been repeatedly wrong in the same direction over recent years.

Then there is the fact that the Bank has revised up its view of the neutral nominal interest rate by 25 basis points. That may well be sensible (respondents to their expectations survey have raised their view of neutral by 60 basis points in the last 18 months), but what it means is that the Bank now thinks the current OCR is less contractionary, all else equal, than it has assumed previously. It is as simple and mechanical as that. With core inflation still holding up, the labour market still tight (in their words), the output gap still positive, and other excess demand indicators still pointing to imbalances, it might then have seemed natural to have moved to raise the OCR, or at least to move the near-term forward track up by 25 basis points, putting October and November firmly into view. Instead, the track is ever so slightly higher in the near-term and the 25 points increase only really becomes apparent in the far (and largely irrelevant) reaches of the years-ahead OCR projections. The MPC was keen on a so-called “least regrets” framework when they were (unintentionally) giving rise to the current mess, but seem to prefer just to punt and hope now.

One of the (many) disappointments around the Reserve Bank’s analysis in recent years – a period when not only do we have a shiny new MPC but the biggest monetary policy failures in decades – is the lack of any really systematic and overarching view of the excess demand pressures that have built up in the economy. They show up, of course, most evidently in the high inflation (which then the Bank too often – see above – tries to minimise with handwaving rhetoric about supply shocks), and it shows (more abstractly) in the Bank’s output gap estimates and (more concretely) in the unsustainably low unemployment rates. But it also shows up in the labour force participation rate, which has stepped up a long way in this boom, tends to be pro-cyclical, and yet the Bank assumes the increase is permanent. Is that likely, and if so why?

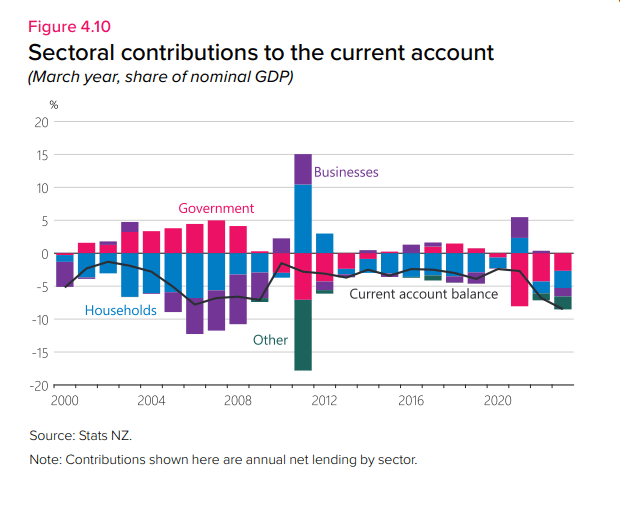

And then there is the sharp widening in the current account deficit, which does not get the attention it deserves as an indicator of macro imbalances and excess demand. As noted already, there is a four page special chapter (and I agree with the bottom line re the NIIP position), but it is rather light on macroeconomic analysis (a basic savings-investment lens) and longer, earlier, on accounting (the absence of Chinese students and tourists). There is a nice sectoral balances chart

and this is where even the Bank has to acknowledge the government contribution to the demand imbalances.

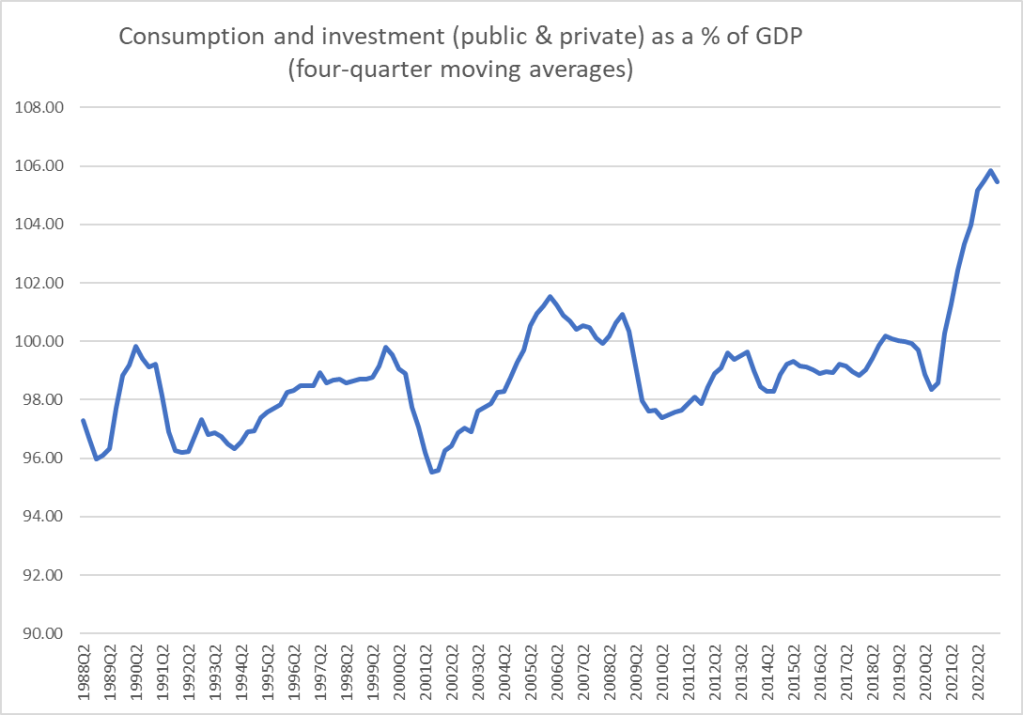

But in playing around with the data yesterday, I came up with this chart

The extent of the domestic pressure on available resources relative to domestic output is quite unprecedented in recent decades (both the consumption and investment lines individually are also around record highs, but it is the combination that is striking). Since GDP is what it is (already stretched beyond potential – that is what a positive output gap is) the excess demand pressures are reflected in a current account deficit. This is annual data. Using the quarterly seasonally adjusted data, the most recent quarterly observation was slightly higher than the last four quarter average. There is a lot of excess demand adjustment that seems likely to have to occur (if, for example, this ratio is to get back to the 98-100 per cent range observed most of the time in the last 35 years).

Central banks are well-positioned to make such points and present data in telling ways. Our mostly does not.

Any new government will face a lot of challenges, and a lot of areas of the public sector that really need sorting out. Given the great power handed to the Reserve Bank, their glaring failures in recent years, and their apparent indifference to matters of integrity, the combination of considerations mean they should be high on the priority list for a new Minister of Finance.