Particularly when he is let loose from the constraints of a published text, the Reserve Bank Governor (never openly countered by any of the other six MPC members, each of whom has personal responsibilities as a statutory appointee) likes to make up stuff suggesting that high inflation isn’t really the Reserve Bank’s fault, or responsibility, at all. It may be that Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee is where he is particularly prone to this vice – deliberately misleading Parliament in the process, itself once regarded by MPs as a serious issue – or, more probably, it is just that those are the occasions we are given a glimpse of the Governor let loose.

I’ve written here about just a couple of the more egregious examples I happened to catch. Late last year there was the line he tried to run to FEC that for inflation to have been in the target range then (Nov 2022) the Bank would have to have been able to have forecast the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2020. It took about five minutes to dig out the data (illustrated in the post at that link) to illustrate that core inflation was already at about 6 per cent BEFORE the invasion began on 24 February last year, or that the unemployment rate had already reached its decades-long low just prior to the invasion too. It was just made up, but of course there were no real consequences for the Governor.

And then there was last week’s effort in which Orr, apparently backed by his Chief Economist (who in addition to working for the Governor is a statutory officeholder with personal responsibilities), attempted to brush off the inflation as just one supply shock after the other, things the Bank couldn’t do much about, culminating in the outrageous attempt to mislead the Committee to believe that this year’s cyclone explained the big recent inflation forecasting error (only to have one of his staff pipe up and clarify that actually that effect was really rather small). See posts here and here. Consistent with this, in his interview late last week with the Herald‘s Madison Reidy, Orr again repeated his standard line that he has no regrets at all about the conduct of monetary policy in recent years. It is consistent I suppose: why regret what you could not control?

It is, of course, all nonsense.

But there is, you see, the good Orr and the bad Orr. The bad – really really bad, because so shamelessly dishonest – is on the display in the sorts of episodes I’ve mentioned in the previous two paragraphs.

The good Orr – some of you will doubt you are reading correctly, but you are – is a perfectly orthodox central banker informed by an entirely orthodox approach to inflation targeting. You see it, even at FEC, when for example he is asked about the role the “maximum sustainable employment” bit of the Remit plays. He has repeated, over and over again and quite correctly as far I can see, that there has not been any conflict between it and the inflation target in recent years. That is how demand shocks and pressures work. And whereas in 2020 the Bank thought inflation would undershoot target and unemployment be well above sustainable levels, in the last couple of years the picture has reversed. He told FEC again last week that when inflation was above target and the labour market was tighter than sustainable both pointed in the same direction for monetary policy: it needed to be restrictive. There was, for example, this very nice line in the MPS, which I put big ticks next to in my hard copy.

The Bank doesn’t do many speeches on monetary policy, and those few they do aren’t very insightful but this from the Chief Economist a few months ago captured the real story nicely

and this from the Governor, describing the Bank’s functions, was him at his entirely orthodox

We aim to slow (or accelerate) domestic spending and investment if it is outpacing (or falling

behind) the supply capacity of the economy

Demand management, to keep (core) inflation at or near target is the heart of the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy job, assigned to it by Parliament and made specific in the Remit given to them by the Minister of Finance.

Domestic demand is known, in national accounts parlance, as Gross National Expenditure (or GNE). It is the total of consumption (public and private), investment (public and private) and changes in inventories.

I’ve been pottering around in that data over the last few days, and put this chart (nominal GNE as a percentage of nominal GDP) in my post last Thursday.

This ratio has tended to be low in significant recessions and high around the peaks of booms – investment is highly cyclical -but for 30+ years it had fluctuated in a fairly tight range. The move in the last couple of years has been quite unprecedented, in the speed and size. There was huge surge in domestic demand relative to (nominal) GDP.

One of the points I’ve made a few times recently is that country experiences with (core) inflation have been quite divergent over the last couple of years. The Minister of Finance in particular is prone to handwaving about “everyone faces the same issue” around inflation, and the Bank isn’t a lot better (doing little serious cross-country comparative analysis). But the differences are large.

And so I wondered about how those domestic demand pressures had compared across countries.

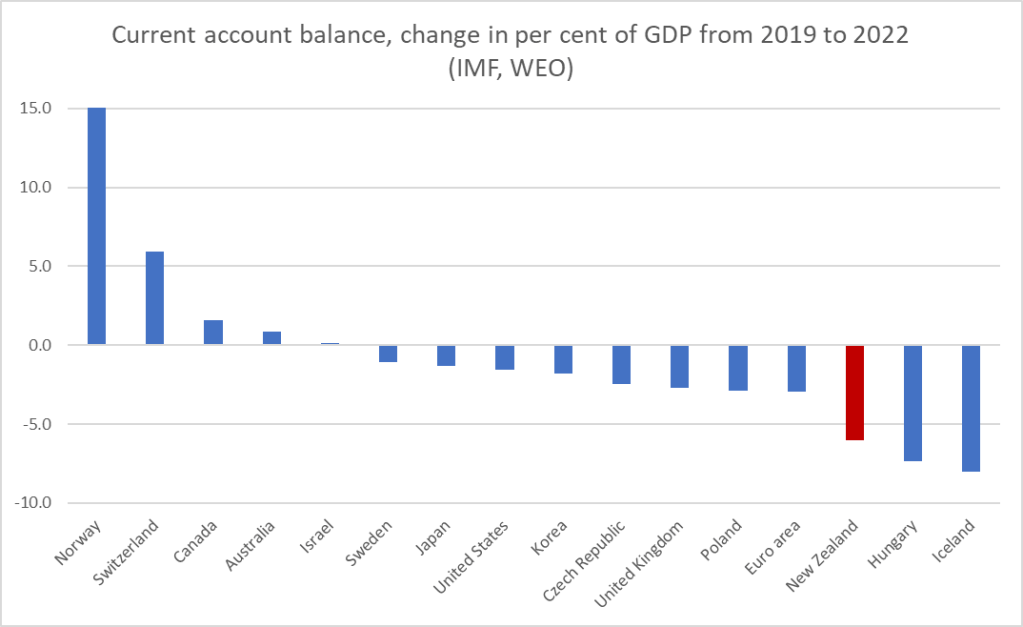

One place to look is to the change in current account deficits as a share of GDP. This chart, using annual data from the IMF WEO database, shows the change in countries’ current account balance from 2019 to 2022 (Norway is off this scale; what happens when you have oil and gas and another major supplier is being shunned)

There has been a fair amount of coverage of the absolute size of New Zealand’s current account deficit, and even a few mentions of the deficit being one of the largest in any advanced country. But for these purposes (thinking about monetary policy and demand management) it is the change in the deficit that matters more. Over this period, New Zealand’s experience has not just been normal or representative, instead we’ve had the third largest widening in the current account deficit of any of these advanced countries (those with their own monetary policy, and thus the euro-area is treated as one). Both Iceland and Hungary have slightly higher inflation targets than we do, but they have a lot higher core inflation (see chart one up).

The current account deficit is analytically equal to the difference between savings and investment. Over that 2019 to 2022 period investment as a share of (nominal) GDP increased in all but two of the advanced countries shown. Of the four countries where it increased more than in New Zealand, three are those with core inflation higher than New Zealand.

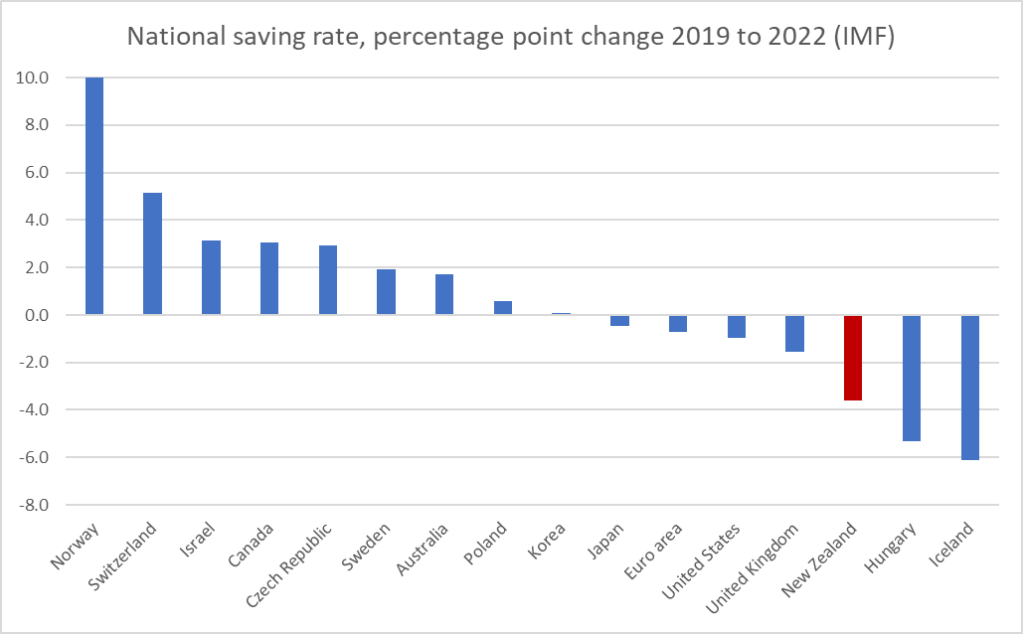

National savings rates (encompassing private and government saving) paint a starker picture. Somewhat to my surprise, of these advanced countries the median country experienced a slight increase in national savings over the Covid/inflation period.

Norway is off the scale again, because I really want to illustrate the other end of the picture. That is New Zealand with the third largest fall in its national savings rate of any advanced country.

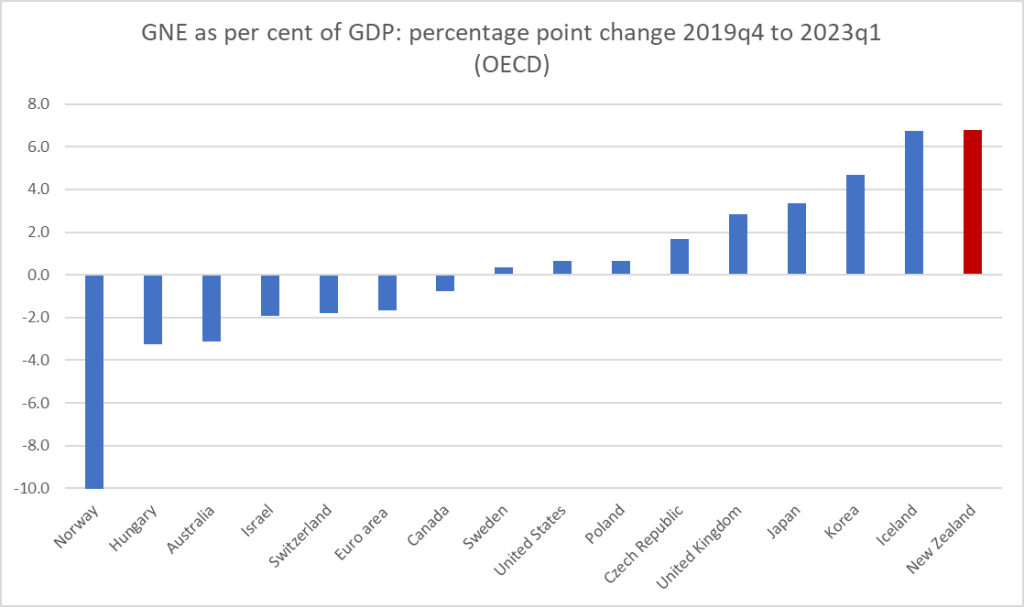

What about that chart of nominal GNE as a share of nominal GDP? How have other countries gone with that ratio? There is a diverse range of experiences, but that sharp rise in the New Zealand share really is quite unusual, equal largest of any of these advanced countries.

(If you are a bit puzzled about Hungary – I am – all the action seems to have been in the last (March 2023) quarter’s data).

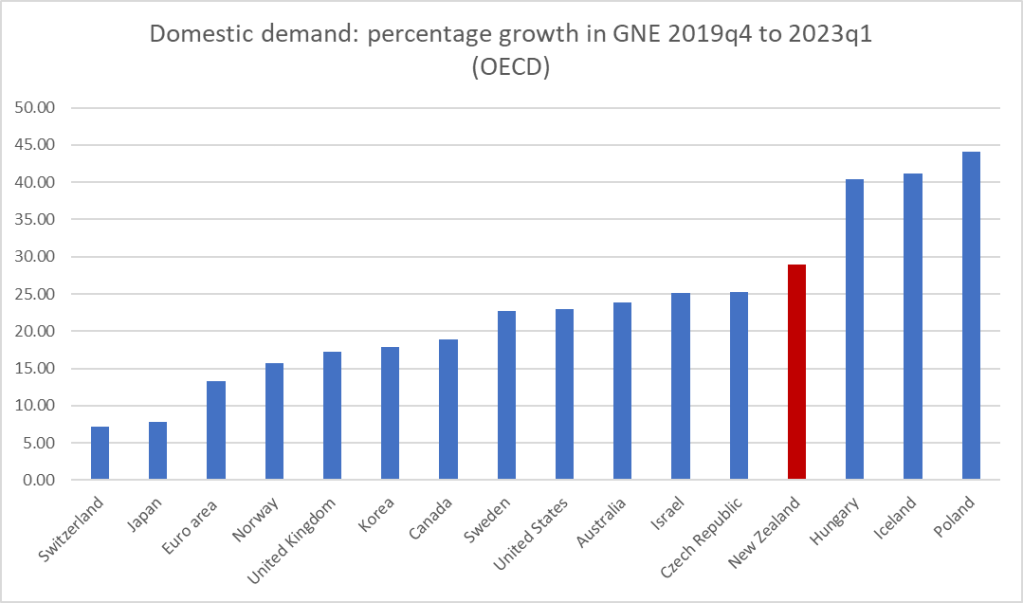

But lets get simpler again. Here is a chart showing the percentage change in nominal GNE (growth in domestic demand, the thing monetary poliy influences) from just prior to the start of Covid to our most recent data, March 2023.

It looks a lot like that earlier chart comparing core inflation rates across countries. In this case, New Zealand had the fourth fastest growth in domestic demand of any of these countries over this period (and those with higher growth are not countries with outcomes we’d like to emulate). And in case you are wondering, no this wasn’t just a reflection of super-strong GDP growth: over this period New Zealand’s nominal GDP growth was actually a little below the growth in the median of these advanced economies. The economy simply didn’t have the capacity to meet the nominal demand growth the Reserve Bank accommodated and the imbalance spilled into a sharp widening of the current account deficit and high core inflation. It wasn’t Putin’s fault, or that of nature (the storms), it was just bad management by the agency charged with managing domestic demand to keep core inflation in check.

I’ve also done all these chart etc using real variables. The deviations are often less marked, but no less substantive for that. Real GNE (real domestic demand) growth from 2019Q4 to the present in New Zealand was third highest among this group of advanced economies, and only Iceland (see inflation and BOP blowouts above) had a larger gap between growth in real domestic demand and real GDP.

I don’t really want to divert this post into an argument about fiscal policy over recent years (monetary policy has to, as the Governor often notes, just take fiscal policy as it is, as just another demand/inflation pressure) but for those interested the government share of GDP has been high (which usually happens in recessions since government activity isn’t very cyclical) but private demand is what really stands out).

Bottom line: all those stories trying to distract people, including MPs, with tales of the evil Russian or the foul weather or whatever other supply shock he prefers to mention, really are just distractions (and intentionally misleading ones by the Bank). The Bank almost certainly knows they aren’t true, but they have served as convenient cover for the fact that the Bank simply failed to recognise the scale of the domestic demand (right here in New Zealand, firms, households, and government) and to act accordingly. We are now still living with the 6 per cent core inflation consequence. It is common – including in the rare Bank charts – in New Zealand to want to compare New Zealand with the other Anglo countries. But what the Bank has never acknowledged – and just possibly may not have recognised – is much larger the boost to domestic demand happened in New Zealand than in the US, UK, Canada or Australia. And domestic demand doesn’t just happen: it is facilitated by settings of monetary policy that were very badly wrong, perhaps more so here than in many of those countries.

Perhaps one could end on a slightly emollient note. Getting it right in the last few years has been very challenging, and it wouldn’t entirely surprise me if when all the post-mortems are done some of relative success and failure proves to have been down to luck (good or bad). But as in life, central banks help make their own luck, but digging deeper, posing and publishing analysis even when they don’t know all the answers, and by taking a coldly realistic view, not attempting to hide behind spin, misrepresentations, and what must come close to outright lies. Even by acknowledging errors, the basis for learning better, and being able to feel and display those most human of qualities, regret and contrition. We need a Governor and MPC members doing all this a lot more than has been on display here in the last year or two. Our lot show little sign of trying, or of even being interested in feigning seriousness.